Katherine Wydville (or Woodville) was born into relative obscurity. Her father was Sir Richard Wydville, a Lancastrian Knight who had made a shocking and advantageous marriage with Jacquetta of Luxembourg, widow of the king’s uncle John, Duke of Bedford. Born around 1458, Katherine was probably the youngest of the couple’s 14 or 15 children. Her eldest sister, Elizabeth, was already married to Sir John Grey and had 2 sons by him.

Little to nothing is known Katherine’s childhood. She did have at least one playmate; her sister, Mary, was just 2 years older than her and it is likely they were raised and educated together.

Katherine may have spent her whole life in obscurity were not for her sister Elizabeth and the fortunes of the Wars of the Roses. In 1461 Elizabeth’s husband was killed in the 2nd Battle of St Albans, fighting for the House of Lancaster. And in 1464 she made the match of the century – and a number of enemies – by her clandestine marriage to England’s handsome, young, Yorkist king, Edward IV.

Suddenly, little 6-year-old Katherine was the sister of the queen – and her marriage prospects had improved considerably. As the daughter of a baron she would have been looking to marry a local knight; as the sister of the queen, her family could now set their sights much higher.

There is considerable debate as to why Edward IV raised the Wydvilles so high. Some historians argue that the king was acting as a good husband and brother-in-law in advancing his wife’s family to the highest positions, arguing that convention required him to make provision for his wife’s siblings. An alternative theory is that Edward was creating a new nobility, binding the great aristocratic houses to his dynasty by marrying them into his extended family, thus creating an alternative power base to rival that of the Nevilles. According to David Baldwin, “Edward could not allow the lowly position of his wife’s relatives to diminish his own status, and, as a usurper, would have seized every opportunity to forge links with the great noble families.”¹

Whatever the reason, the end result was a series of marriages of the Wydville siblings into the great noble houses of the realm. Of Elizabeth’s sisters Margaret became Countess of Arundel, Anne became Countess of Kent, Jacquetta married Lord Strange of Knokyn and Mary married the Earl of Huntingdon. The most shocking marriage arrangement was that of Elizabeth’s brother, 19-year-old John, to the Dowager Duchess of Norfolk, 65-year-old Katherine Neville.

Young Katherine Wydville’s marriage was to be one of the most exalted; even before Queen Elizabeth’s coronation in 1465, 6-year-old Katherine was married to Henry Stafford, the 11-year-old Duke of Buckingham. David Baldwin describes the scene at Elizabeth’s coronation:

The peers included young Henry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham ‘born a pon a squyer [squire] shouldr’, and among the ladies was his new wife, Catherine Woodville, likewise carried…¹

The event must have been awe-inspiring for the children; the sumptuous costumes, the roar of the crowds. The Queen was attended by 13 duchesses and countesses dressed in red velvet, 14 baronesses in scarlet and miniver, and the ladies of 12 knights bannerets wearing scarlet.¹ One can only imagine the effect such an auspicious day could have on 2 young children who were right in the middle of the celebrations.

Katherine’s new husband, Henry Stafford, had been Duke of Buckingham since the age of 4; his father, Humphrey Stafford, had been wounded at the 1st Battle of St Albans and died of natural causes in 1458 and his grandfather, Sir Humphrey Stafford, 1st Duke of Buckingham, was killed at the Battle of Northampton in 1460; both were loyal supporters Henry VI and the House of Lancaster. This left 5-year-old Henry as Duke and in the care of his grandmother Anne Neville (sister of Cecily, the new king’s mother).

Following Edward IV’s marriage to Elizabeth Wydville in 1464, Henry and his younger brother were given into the custody of the new queen, who was granted 500 marks out of the young duke’s Welsh lands – soon increased by a further £100 – for the maintenance of the 2 boys. John Giles, who later be employed as tutor to Edward IV’s sons, taught grammar to ‘the queen’s beloved brothers’ during 1465-7.²

The Stafford boys remained in the queen’s custody, along with the duke’s little wife, Katherine, until the Readeption of Henry VI in 1470-71 when the duke was again returned to the custody of his grandmother and her new husband, Walter Blount, Lord Mountjoy. His younger brother, Humphrey, had disappeared from the records by this point, probably having succumbed to a childhood illness.

By June 1473, still only 17, Buckingham was granted his livery as a duke and his grandfather’s estates. Although Edward IV had returned to the throne, he appears to have had no great love for Duke Henry and he was rarely at court; staying mainly on his estates with his wife and family.

According to Domenico Mancini, writing in 1483, Buckingham resented his marriage due to his wife’s ‘humble origin’ and his wife certainly brought no marriage portion with her and has often been described as a ‘parvenu’ by historians.² However, the couple did have 5 children together, 4 of whom survived childhood.

Edward Stafford, the future 3rd Duke of Buckingham, was born in 1478. He would go on to marry Eleanor (d. 1530), the daughter of Henry Percy, 4th Earl of Northumberland, before his execution in 1521, during the reign of Henry VIII.

A 2nd son, Henry, Earl of Wiltshire, was born around 1479 and died in 1523. He married twice, firstly to Muriel or Margaret, daughter of Edward Grey, Viscount de Lisle and secondly to Cecilia, daughter of William Bonville, Baron Harrington.

A 3rd son, Humphrey, died young, but was followed by 2 daughters. Anne married Sir Walter Herbert who died in 1507. She then married George Hastings, Earl of Huntingdon. Katherine and Henry’s youngest daughter, Elizabeth, married Robert Radcliffe, Earl of Sussex, by whom she had 3 sons.

With Edward IV’s death in 1483, Buckingham played a leading role in the turmoil which saw Edward’s 2 sons by Elizabeth Wydville declared illegitimate, and saw the late king’s brother, Richard of Gloucester claim the throne as Richard III. For a time, Buckingham was Richard’s staunchest ally and played a major role in Richard’s coronation – an event his wife Katherine, as one of the now-despised Wydvilles, did not attend.

However, by October 1483, and for still-unknown reasons, Buckingham mounted a coup against Richard, entering an alliance with Henry Tudor – in exile in Brittany – he attempted to raise Lancastrian support in the Welsh Marches. Katherine accompanied her husband from Brecon to Weobley, leaving her daughters at Brecon. Thwarted by the weather, the coup failed and Buckingham attempted to flee.

The Duke was arrested and executed at Salisbury on 2nd November 1483. The duchess and her youngest son, Henry, were captured and taken to London. Her eldest son, Edward, was also in the king’s custody. In December 1483, Katherine was allowed to have her servants and daughters brought to London from Wales. However, having been deprived of her dower and jointure, her financial position was precarious, until Richard III granted her an annuity of 200 marks.

Katherine’s situation was changed again following Henry VII’s defeat of Richard III at Bosworth. Katherine was married to Jasper Tudor, the new king’s uncle and newly created Duke of Bedford, before 7th November 1485. The new regime reversed Buckingham’s attainder, awarding Katherine not only her dower rights, but also a jointure of 1000 marks, as specified in Buckingham’s will.

This took her total revenue from the Buckingham estates to £2500 and therefore bolstered her new husband’s position as the representative of the king in Wales. Jasper had practically raised the new king single-handedly, sharing his exile in Brittany following the defeat of the Lancastrian cause at Tewkesbury in 1471. Katherine, a dukedom and becoming the king’s right-hand man in Wales; this was his reward.

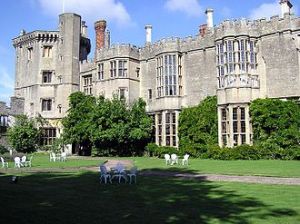

As with most medieval marriages, we cannot know if there was any affection in Katherine’s relationships with either of her 1st 2 husbands; both marriages were made for political reasons. During her 2nd marriage, Katherine resided mainly at Thornbury in Gloucestershire, she and Jasper Tudor had no children together and her estates were kept under a separate administration to Tudor’s own lands.

Jasper Tudor died at Christmas, around the 21st December, 1491. Poor Katherine only gets a passing mention in his will; “I will that my Lady my wife and all other persons have such dues as shall be thought to them appertaining by right law and conscience.”³

I can’t help hoping that Katherine found some affection and comfort in her 3rd and final marriage. By 24th February 1496 Katherine had married Richard Wingfield, a man 12 years her junior. They married without royal licence, the fine for which remained unpaid at Katherine’s death. Wingfield was probably in the duchess’s service before the marriage, as his 2 brothers, John and Edmund appear to have been. When he married Katherine he was a younger son in a rather large family, with few prospects as a consequence. However, he would go on to have a distinguished diplomatic career under Henry VIII, dying at Toledo in 1525.

Katherine herself died on 18th May 1497. The unpaid fine, imposed following her marriage to Wingfield, became a charge on her eldest son, Edward, the 3rd Duke of Buckingham. Her 3rd husband, however, did not forget her; despite remarrying, his will, drawn up in 1525, requested masses be said for the repose of Katherine’s soul.

*

Footnotes: ¹David Baldwin in Elizabeth Woodville; ²C.S.L. Davies in Oxforddnb.com; ³The Woodvilles by Susan Higginbotham.

*

Pictures taken from Wikipedia.

*

Sources: The Woodvilles by Susan Higginbotham; Elizabeth Woodville by David Baldwin; Brewer’s British Royalty by David Williamson; History Today Companion to British History Edited by Juliet Gardiner and Neil Wenborn; Britain’s Royal Families, the Complete Genealogy by Alison Weir; Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville, A True Romance by Amy Licence; The Wars of the Roses by John Gillingham; The Oxford Companion to British History Edited by John Cannon; The Mammoth Book of British kings & Queens by Mike Ashley; Oxforddnb.com.

*

My Books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online store.

Out now: Scotland’s Medieval Queens

Scotland’s history is dramatic, violent and bloody. Being England’s northern neighbour has never been easy. Scotland’s queens have had to deal with war, murder, imprisonment, political rivalries and open betrayal. They have loved and lost, raised kings and queens, ruled and died for Scotland. From St Margaret, who became one of the patron saints of Scotland, to Elizabeth de Burgh and the dramatic story of the Scottish Wars of Independence, to the love story and tragedy of Joan Beaufort, to Margaret of Denmark and the dawn of the Renaissance, Scotland’s Medieval Queens have seen it all. This is the story of Scotland through their eyes.

‘Scotland’s Medieval Queens gives a thorough grounding in the history of the women who ruled Scotland at the side of its kings, often in the shadows, but just as interesting in their lives beyond the spotlight. It’s not a subject that has been widely covered, and Sharon is a pioneer in bringing that information into accessible history.’ Elizabeth Chadwick (New York Times bestselling author)

Available now from Amazon and Pen and Sword Books

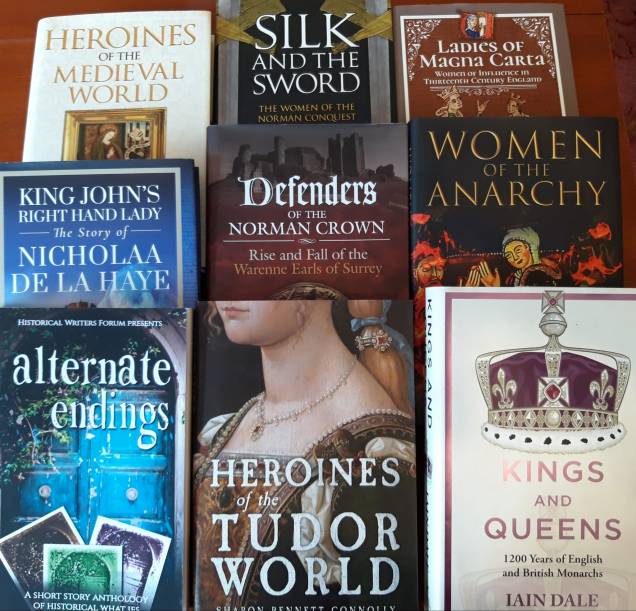

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

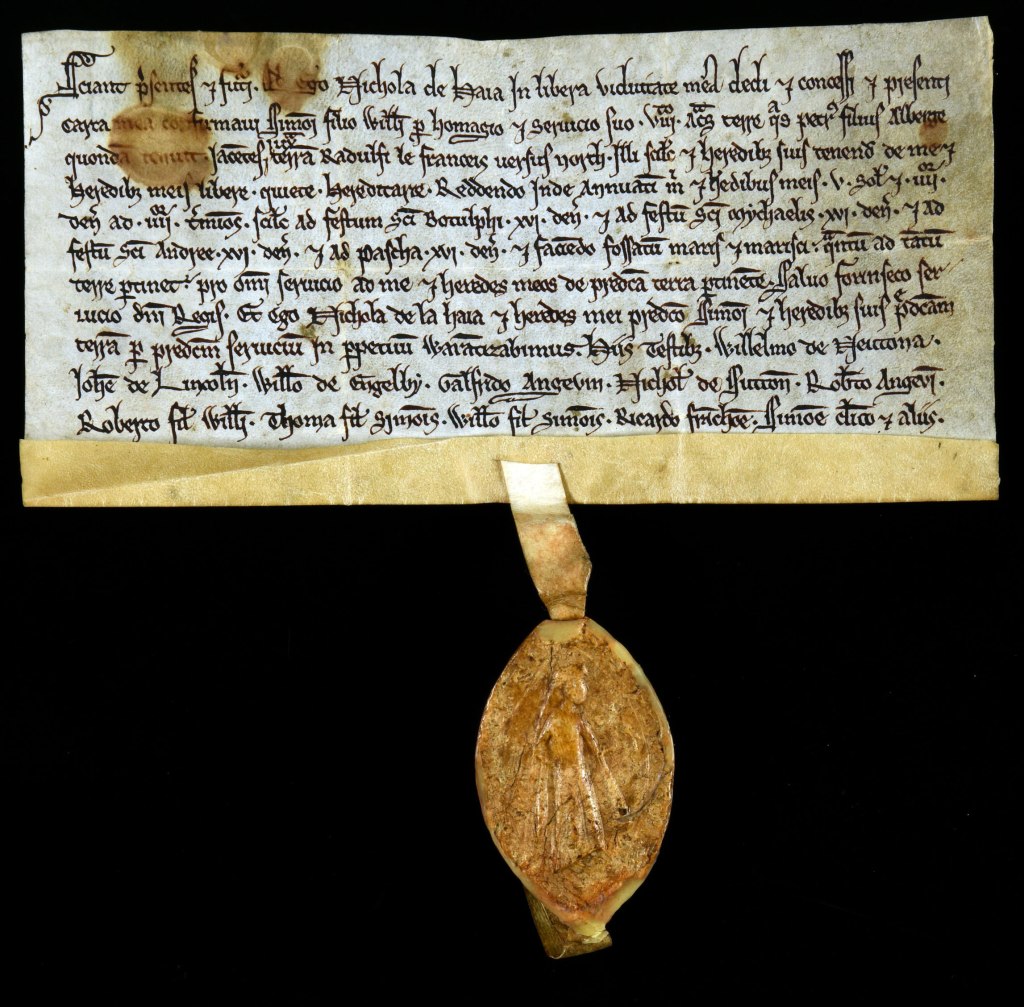

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. Heroines of the Tudor World is now available from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how Empress Matilda and Matilda of Boulogne, unable to wield a sword themselves, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It shows how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other. Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org. Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved. In episode #43, Derek and I chat with Carol about Berengaria of Navarre and The Lost Queen.

Every episode is also now available on YouTube.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online store.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter, Threads, Bluesky and Instagram.

*

© 2016 Sharon Bennett Connolly, FRHistS