Today it is a pleasure to welcome Alistair Forrest to History…the Interesting Bits, with an article about the history behind the biblical story of David and Goliath.

David & Goliath

Making the facts fit the story!

ALISTAIR FORREST draws on an upbringing in the Middle East and a love of ancient history to explore fact and fiction surrounding a famous Bible story

I’m an author of fiction, not a historian. So I can assure you that some historians reading Line in the Sand, my account of the David & Goliath story, might get very hot under their academic collars.

I hope lovers of historical fiction will take a different view and accept that I have filled in some gaps that the ancient scribes left in their telling. We know there are inconsistencies and contradictions across the several Biblical books that report the story of King David, leaving many questions unanswered.

So, following my journalist’s mantra, ‘Never let the facts get in the way of a good story’, I have drawn on my studies of the ancient Near East and Old Testament history – let’s call these ‘the facts’ – and unleashed my imagination and love of ‘a good yarn’.

In reality, there are very few facts. The only archaeological reference to King David would appear to be a reference to the House of David on a ninth century stela found at Tel Dan in northern Israel in 1993. Most of the Biblical texts were written down long after the events surrounding David’s rise to power, with the two books of Samuel the earliest account.

Fair game, then? I decided that this bullied young shepherd should become a spy, find himself betrayed in the Philistine city where giants lived, be tortured and face branding as a slave, fight a giant called Golyat (Goliath) in a gladiatorial arena, rescue a Philistine princess and ultimately escape to warn the Israelites of pending doom.

You might think you know what happens next. I couldn’t possibly comment. But then, I have tried to anchor the story in certain Biblical facts, such as the tensions between the agricultural kingdom of Judah and the five Philistine city states, and the settling of scores in single combat (and who wouldn’t nominate a nine-foot warrior as champion?).

Which brings us to Goliath, or more accurately, ‘Golyat’.

At the outset of writing Line in the Sand, I listened to a very convincing lecture by Professor Jeffrey R. Zorn of Cornell University, entitled Who Was Goliath?, in which he suggests that the Philistine giant was an elite chariot warrior. Most modern depictions of Goliath are as a very large foot-soldier, but Zorn points out his armour and weapons as detailed in 1 Samuel 17: 4-7 would indicate an Aegean/Levantine chariot warrior who was probably transported to the ideal position in a battle to wreak the most havoc.

While researching for the book, I was in touch with Professor Aren Maier, director of the Tel es-Safi excavations that have uncovered so much about ancient Gath, whence the giant came, including an inscription thought to include his name or at least something similar.

I am also indebted to the British Egyptologist and author David Rohl, not least for succinct explanations of his New Chronology theories, specifically his interpretation of the Amarna letters and probable references to King Saul.

Books that have helped me include the Bible of course, The King David Report by Stefan Heym; The Source by James A. Michener; David’s Secret Demons by Baruch Halpern, and various books published by Osprey about warfare in the ancient Middle East.

I have read many books about ancient Israel both on-line and in my studies, too numerous to mention, all influential in their way. But somehow I still feel as though I know nothing when compared with the likes of Maier, Zorn and Rohl. I hope these knowledgeable historians will forgive my diversion from ‘what is known’ to ‘what might have been’.

What next? I count myself lucky to have spent my childhood and early teens in three Middle Eastern countries and subsequently to have travelled widely as a journalist, always delving into the history that made each place what it is today. A burning passion to write historical fiction fuelled by two years studying theology straddled by my early years as a newspaper reporter.

Although currently focusing on post-Republic Roman themes at the behest of my publisher Sharpe Books, especially the upheaval following the assassination of Julius Caesar (Libertas, Nest of Vipers), I hope one day to return to my formative years in the Middle East and extensive studies of ancient Mesopotamia, including the amazing stories waiting to be reimagined of Assyrians, Israelites, Phoenicians and Philistines.

And while there’s ink my pen, I must surely make the most of the archaeological dig just a few yards from my home in Alderney (Channel Islands) where archaeologists Jason Monaghan and Phil de Jersey have uncovered well-preserved remains of Roman and Iron Age settlements. The historian Dan Snow is keenly interested in the site. But that’s yet another story…

I would like say a huge thank you to Alistair for such a fascinating article and wish him all the best with his latest book.

Line in the Sand

(Sharpe Books 2020)

1000 BC

His mother is reviled as a whore and his half-brothers despise him.

The best Dhavit of Beth Lechem can do is escape. But just as life couldn’t get much lower for the youth they call Leper, he is recruited as a spy. His mission – to find out about the superior weapons and invasion plans of the warlike Philistines.

When he is betrayed, Dhavit is thrown into an arena with two other misfortunates to fight a pair seemingly invincible warriors. Only speed and quick wits can save him.

Dhavit believes he is chosen by the gods and finds himself revered in the Philistine court, whose rulers want to declare war on his people.

At the head of the Philistine forces is the famed Golyat, a man bred for war and destruction.

A vicious conflict for supremacy is sure to follow.

Two armies will go to war. But also two soldiers – Dhavit and Golyat.

A king and country will rise.

To buy the book:

About the author:

Alistair Forrest is a journalist, editor and author of historical fiction. He has worked for several UK newspapers, edited magazines in the travel, photographic and natural products sectors, and owned a PR company.

He lives in the Channel Islands with his wife Lynda. They have five children, two Maremma dogs and a Spanish cat, Achilles. His books are published by Sharpe Books of London. Alistair loves to hear from readers.

Alistair Forrest is the author of Libertas and Nest of Vipers.

You can find Alistair Forrest:

Twitter Handle: @alistairforrest

Website: https://www.alistairforrest.com

*

My Books

Coming soon!

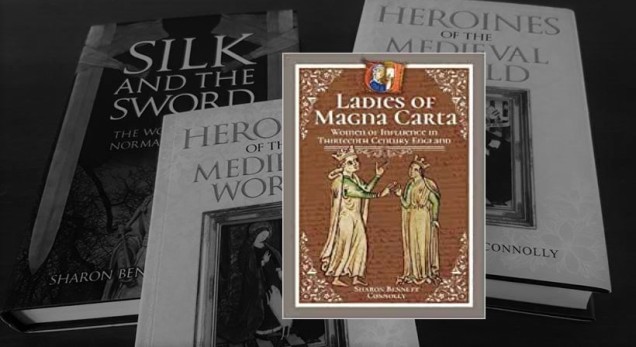

Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England will be released in the UK on 30 May 2020 and is now available for pre-order from Pen & Sword, Amazon UK and from Book Depository worldwide. It will be released in the US on 2 September and is available for pre-order from Amazon US.

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon UK, Amberley Publishing, Book Depository and Amazon US.

Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK, Amazon US and Book Depository.

*

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

©2020 Sharon Bennett Connolly and Alistair Forrest