The history of women in medieval Wales before the English conquest of 1282 is one largely shrouded in mystery. For the Age of Princes, an era defined by ever-increased threats of foreign hegemony, internal dynastic strife and constant warfare, the comings and goings of women are little noted in sources. This misfortune touches even the most well-known royal woman of the time, Joan of England (d. 1237), the wife of Llywelyn the Great of Gwynedd, illegitimate daughter of King John and half-sister to Henry III. With evidence of her hand in thwarting a full scale English invasion of Wales to a notorious scandal that ended with the public execution of her supposed lover by her husband and her own imprisonment, Joan’s is a known, but little-told or understood story defined by family turmoil, divided loyalties and political intrigue. From the time her hand was promised in marriage as the result of the first Welsh-English alliance in 1201 to the end of her life, Joan’s place in the political wranglings between England and the Welsh kingdom of Gwynedd was a fundamental one. As the first woman to be designated Lady of Wales, her role as one a political diplomat in early thirteenth-century Anglo-Welsh relations was instrumental. This first-ever account of Siwan, as she was known to the Welsh, interweaves the details of her life and relationships with a gendered re-assessment of Anglo-Welsh politics by highlighting her involvement in affairs, discussing events in which she may well have been involved but have gone unrecorded and her overall deployment of royal female agency.

Finally!

I have got my hands on this much-anticipated book, Joan, Lady of Wales by Danna R. Messer. I have to admit, I devoured every word. Joan has been in need of a biographer for some time, and I am so pleased that Danna took up the challenge and produced this remarkable study of the illegitimate daughter of King John who became Lady of Wales as the wife of Llywelyn ap Iorweth – Llywelyn Fawr.

Ever since I have known this book was being written, I have been itching to get my hands on it!

Anyone who is a fan of Sharon Penman will have heard of Joan, and most likely have a soft spot for this incredible woman. This biography gives you the chance to study the facts, to meet the woman behind the story and read of how deeply involved she was in Anglo-Welsh relations in the first half of the 13th century. Danna R. Messer portrays a politically astute and powerful woman, aware of her duty, importance and capabilities, not only as the daughter and sister of England’s kings, but also as Llywelyns wife and consort – and as the mother of his heir.

Beautifully written, with clear, concise arguments and a passion for her subject, the author has brought Joan to life. This is a book that is impossible to put down. Danna R. Messer does not shy away from areas of controversy, either, examining every aspect of Joan’s relationship with William de Braose, the man who was hanged after being found with Joan in Llywelyn’s chamber. the deconstruction of the event, the aftermath and the repercussions make for fascinating reading – its worth getting the book just to discover how everything unfolded.

As are all life stories, that of Joan of England’s is complicated; the complexities of which are further irritated by a dearth of contemporaneous material related to her. The identity of her mother remains a mystery and is much debated by today’s genealogists, as is who her children were. how many she really had and where some even ended up in their own lives. How many times she travelled as an envoy, how many charters she issued and just how fully she participated in effecting Welsh polity can never be fully known. No matter the daunting aspect of approaching such an ill-documented existence, which is a painstaking project indeed, it is one that yields both exciting and long-overdue results.

This study of Joan of England seeks to revise the master narrative of native medieval Wales in the early-thirteenth century – to generate a better ad more inclusively nuanced understanding of the history of this fascinating and wild region of Britain and its relationship with England by placing this particularly interesting and fascinating woman at the forefront in the sequence of events…

Although Siwan’s role in Anglo-Welsh history has received recognition by historians, she has been still largely relegated to the sidelines; an indication that her role was not entirely critical to the stability and growth of Welsh polity, or peace with England overall. On the flip side, it is sometimes difficult not to naturally overplay our hand and emphatically conclude that Joan was, indeed, a heroine and that if it were not for her, the very fabric of native Wales would have been fundamentally altered by the time Llywelyn died in 1240. On balance, however, it is vitally important to understand that the aggregate of Joan’s interventions in the early-thirteenth century ensured that she really was a crucial player in the political wranglings between the ruler of Gwynedd and the rulers of England. The famous early-twentieth-century Welsh historian J.E. Lloyd concluded that Llywelyn ap Iorweth ‘had one emissary whose diplomatic services far outran those of the seneschal and who helped him in this capacity for the greater part of his reign. To the assistance of his wife Joan, both as advocate and counsellor, there can be no doubt he was much indebted.’ To the assistance of Joan, Lady of Wales, there can be no doubt that the history of native medieval Wales is also much indebted.

Joan, Lady of Wales by Danna R. Messer not only examines every aspect of Joan’s life, but places that life in the wider context of English and Welsh events, of Anglo-Welsh relations and of the place of women in Welsh society and history in general. This in-depth study provides an overview analysis of the status of women in Welsh history, the laws surrounding marriage and adultery, legitimate and illegitimate children and demonstrates how Joan’s own confirmation of legitimacy in the 1220s added prestige and legitimacy to her husband’s position within Wales and the wider sphere of Anglo-Welsh relations.

Danna R. Messer also explores the use of title and authority for women in the 13th century, depicting Joan as a queen, both in her actions and relationship with others. Although she was not crowned and anointed in the same manner as an English queen would be, she held the same level of authority and respect, both in the public and the private sphere of the Welsh court.

A collection of a bout 20 black and white photos help to illustrate Joan’s story, Joan, Lady of Wales is a stunning, comprehensive study of the unique character and position that Joan occupies in both English and Welsh history.

Despite a woeful lack of sources mentioning Joan, Danna has managed to tease out every piece of information she could find on Joan and her position and duties, not only in Wales as the wife and consort of Llywelyn, but also in England as the daughter and, later, sister of the king. Joan’s status as the primary diplomat in Anglo-Welsh relations comes through clearly in the way Joan was treated by her husband and the rewards she was given by the English crown.

In brief, in Joan, Lady of Wales, Danna R. Messer recreates the life and times of this incredible woman, giving us a more complete portrait than has ever been achieved since her own lifetime. We are given a full and complete analysis – as far as the sources and distance of time will allow – of Joan’s political and personal life, the good and the bad, including the scandal, the ambition and Joan’s own legacy and what it meant for those who followed her.

Joan, Lady of Wales has long needed her own biography, to bring her out from the shadows of the lives of her father, brother, husband and son – and this book does not disappoint. It is, quite simply, a beautifully-executed, fascinating and addictive read.

Joan, Lady of Wales is available in hardback from Pen &Sword and Amazon.

About the author:

Dr Danna R. Messer has published on various aspects of the wives of the native Welsh rulers before 1282, providing a gendered perspective of medieval Welsh politics. As an editor and historian, she is widely involved in medieval history and queenship studies generally, including her roles as Series Editor for Medieval History for Pen and Sword, editor for the Royal Studies Journal and editor for Normans to Early Plantagenet Consorts, the first volume of the forthcoming four-book series, English Consorts: Power, Influence, Dynasty (Palgrave). She is also Acquisitions Editor for Arc Humanities Press and the Executive Editor for the Encyclopedia of the Global Middle Ages, a partnership project with Bloomsbury Academic and Arc Humanities Press.

*

My Books

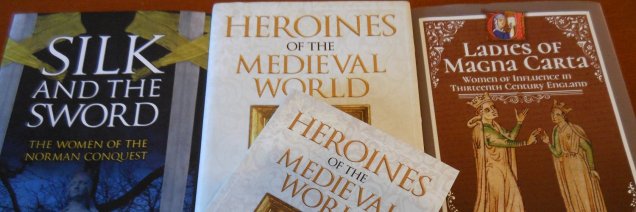

Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available from Pen & Sword, Amazon and from Book Depository worldwide.

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, Book Depository.

Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon and Book Depository.

*

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

©2020 Sharon Bennett Connolly