One of 4 sisters, all of whom became queens, Sanchia of Provence was born in Aix-en-Provence in about 1228. She was the third daughter of Raymond Berengar V, Count of Provence, and his wife Beatrice of Savoy.

Sanchia was 7 years younger than her oldest sister, Marguerite, who married Louis IX of France in 1234. Her second oldest sister, Eleanor, was 5 years her senior and married Henry III of England in 1236. Sanchia probably spent most of her childhood with Beatrice, who, as the youngest of the 4 sisters, was 3 years younger than Sanchia and didn’t marry until 1246; she would become Queen of Naples in 1266.

I could find no information on Sanchia’s childhood, beyond the fact that the sisters were all close, and remained so throughout their lives; thus helping to forge international relations through their exceptional familial bond.

The one description I could find of Sanchia was that she was ‘of incomparable beauty’.

Sanchia had originally been married, by proxy, to Raymond VII of Toulouse; however Raymond had failed to obtain an annulment of his previous marriage and the arrangement was declared void. In the mean time Richard, Earl of Cornwall and brother of Henry III of England visited Provence in 1241; he saw in Sanchia the chance to ally himself more closely with his brother’s interests, whilst at the same time strengthening his family’s position on the continent.

Richard and Sanchia were betrothed by proxy in July 1242, following negotiations at Tarascon, led by Sanchia’s uncle, Peter of Savoy, and the Savoyard bishop of Hereford, Peter d’Aigueblanche.

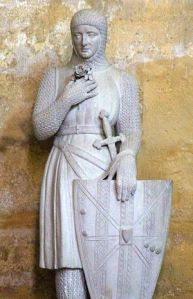

Richard was the second and youngest son of King John of England and Isabella of Angoulême. Born in 1209, he was just 7 years old when his father died. A renowned soldier, Crusader, negotiator and administrator, Richard was one of the wealthiest men in Europe. He already had a son, Henry of Almain by his first wife, Isabella Marshal, daughter of the great William Marshal Earl of Pembroke. Isabella had died in childbirth in January 1240, after giving birth to a second son, who was stillborn.

In August-September 1242, following a failed campaign against Louis IX with his step-father, Hugh de Lusignan, Richard had planned to visit his future bride in Provence, before returning to England. However a falling-out with his brother, Henry III, and a fear of kidnapping forced Richard to change his plans and head straight for home, thus delaying a reunion with his bride-to-be.

Sanchia arrived in England in 1243. She and Richard were married in Westminster Abbey on 23rd November 1243. Sanchia was a girl of about 15, while Richard was 34. On his marriage, Richard confirmed in his possession of Cornwall and the honours of Wallingford and Eye. He was also given £2000 in cash by the king, and a promise of 1000 marks a year, in return for a renunciation of all claims to lands in Gascony and Ireland.

Richard’s marriage to Sanchia greatly improved his relations with the Savoyards, a powerful contingent of the queen’s relatives living in England. Following the marriage Richard served Peter of Savoy, titular earl of Richmond, as a banker and political ally.

Richard and Sanchia had only 2 children. Their eldest son, Richard, was born at Wallingford in July 1246 and died there the following month; the little baby was buried at Grove Mill. Another son, Edmund, was born at Berkhamsted on 26 December 1249 and was baptised by his mother’s uncle, Boniface of Savoy, Archbishop of Canterbury. He would be knighted at the age of 22 and married Margaret, the daughter of Richard de Clare. However, the marriage was childless and the couple officially separated in February 1294.

Edmund had departed on crusade with the king’s son and heir, Edward (the future Edward I) when he heard of the murder of his older brother, Henry of Almain (son of Richard and his 1st wife, Isabella Marshal), who was murdered in Viterbo by the sons of Simon de Montfort. Edmund returned home to his father, who died the following year, leaving Edmund as the 2nd Earl of Cornwall. With no heir to succeed him, the earldom reverted to the crown on Edmund’s death in 1300.

In 1246 Sanchia’s father, Raymond Berengar V, died, leaving Provence to the youngest of his daughters; Beatrice was the only daughter still unmarried. Several suitors now set out to ‘win’ the heiress and her mother appealed to the pope for protection. The pope and Louis IX together decided that the most appropriate husband for Beatrice was Louis’ brother, Charles of Anjou. Beatrice’s mother offered no objection; however Henry III and Richard sought – unsuccessfully – to oppose the marriage, unsurprising when you consider their wives were denied their share of their father’s inheritance.

Sanchia and her sister, Eleanor, were not as cut off from their family as most royal brides of the period appear to have been. Their mother, Beatrice of Savoy, arrived in England in 1248 with her brother, Thomas, to visit both her daughters.

Sanchia also accompanied her husband on an embassy to the French court in 1250, taking the opportunity to meet with her big sister, Marguerite; and possibly her little sister Beatrice, who was by then married to Charles of Anjou. Sanchia also joined the family gathering in Chartres and Paris in 1254, when Louis IX and queen Marguerite received Henry III and queen Eleanor; Her mother Countess Beatrice and youngest sister Beatrice were also present.

Sanchia and her sister Eleanor seem to have been in close contact ever since Sanchia arrived in England. Henry III officially recognised Sanchia as a voice in family dynastic matters. In the 1253 Calendar of Patent Rolls, she is included in a grant to her uncle, Peter of Savoy:

“Grant to Peter de Sabaudia that if he have an heir male of his wife, he may assign or bequeath the lordship of his lands and heir to whom he will. The king also wills that the said heir shall not be married to anyone without the consent of Queen Eleanor and Sanchia, countess of Cornwall, and the brothers of the said Peter.”

Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1253

Sanchia seem to have had some influence in pleading for others. The Patent Rolls of 1255 record her achieving a pardon for a man who received an outlaw and again, in 1256, they record her gaining a licence to a man to enclose a wood.

Henry III had made attempts to gain his brother a crown; he had accepted the crown of Sicily, offered by the pope, on his brother’s behalf, but the enterprise to recover the kingdom from the Hohenstaufens proved beyond the king’s means. In 1256, however, another opportunity arose with the death of William of Holland, papal candidate to be Holy Roman Emperor. With the support of his brother and his considerable wealth, diplomatic skills and imperial connections, Richard set about earning his election to the Empire.

On 26 December 1256 the crown of Germany was offered to Richard by the archbishop of Cologne. with his rival, King Alfonso of Castile, too busy with troubles at home to travel to Germany to claim the crown; Richard and Sanchia, with a large entourage including their son Edmund, but only half of the electors on their side, made their way to Aachen.

Sanchia and Richard were crowned as king and queen of Germany on 17 May 1257, by the archbishop of Cologne; being styled as the king and queen of the Romans, Richard still needed papal ratification to become Holy Roman Emperor. The coronation was followed by a splendid feast for Richard’ supporters before the new king and queen departed on progress around their new kingdom. Richard held his 1st royal parliament, or diet, in Mainz in September, and another progress in the spring of 1258 was spent confirming imperial privileges and issuing charters.

However, papal confirmation of Richard’s titles were not forthcoming and in the winter of 1258/9 Richard and Sanchia returned home to an England riven by baronial rebellion. Richard acted as mediator between his brother the king and his brother-in-law, Simon de Montfort, leader of the baronial opposition.

The political situation was still unresolved when Sanchia died at Berkhamsted on 9th November 1261 and was buried at Hailes Abbey 6 days later; her husband was absent from her death-bed and funeral.

After Sanchia’s death a grant in the Patent Rolls of Henry III:

“for the saving of the king’s soul and of Sanchia, queen of Almain [Germany], to the master and brethren of the hospital of St Katharine without the Tower London of 50s a year at the Exchequer for the maintenance of a chaplain celebrating divine service daily in the chapel of St John within the Tower for her soul”.

Although she was only about 33 at her death, Sanchia’s legacy came from the close relationship with her sisters. All 4 sisters, and their mother, took part in the negotiations which led to the 1259 Treaty of Paris, improving relations between the French and English kings.

*

Pictures courtesy of Wikipedia

*

Sources: The Plantagenet Chronicles edited by Elizabeth Hallam; The Story of Britain by Roy Strong; The Plantagenets, the Kings Who Made England by Dan Jones; England Under the Norman and Angevin Kings by Robert Bartlett; oxforddnb.com; Brewer’s British Royalty by David Williamson; epistolae.ccnmtl.columbia.edu

*

My Books

Christmas is coming!

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

Coming 15 January 2024: Women of the Anarchy

On the one side is Empress Matilda, or Maud. The sole surviving legitimate child of Henry I, she is fighting for her birthright and that of her children. On the other side is her cousin, Queen Matilda, supporting her husband, King Stephen, and fighting to see her own son inherit the English crown. Both women are granddaughters of St Margaret, Queen of Scotland and descendants of Alfred the Great of Wessex. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how these women, unable to wield a sword, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It show how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other.

Available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK.

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Out now: King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady. Nicholaa de la Haye was the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Her strength and tenacity saved England at one of the lowest points in its history. Nicholaa de la Haye is one woman in English history whose story needs to be told…

King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is now available from Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, of the successes and failures of one of the most powerful families in England, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Defenders of the Norman Crown: Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey is now available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org.

Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org.

Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org.

Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell, and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

*

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

©2015 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS

Reblogged this on Lenora's Culture Center and Foray into History.

LikeLike

Thank you. 🙂

LikeLike

Edmund was born in 1249.

LikeLike

Thank you, I missed that typo.:)

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Tome and Tomb.

LikeLike

Wonderful. Thank you. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve been to Hailes Abbey a few times. The church standing next to it has wonderful wall paintings, including Richard of Cornwall’s eagle.

LikeLike

Oh how marvelous. Thank you 🙂

LikeLike

Hailes Abbey is a fave place of mine, I lived nearby for 22 years. It is wonderfully peaceful.. How wonderful to know that Sanchia is buried there.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on History's Untold Treasures and commented:

H/T History … the Interesting Bits

LikeLike

Thank you ☺

LikeLike