Few periods in history have brought women to the fore, to the centre of events, as the Anarchy did in England. From 1135 to 1154, conflict raged when Stephen of Blois usurped the throne that rightfully belonged to his cousin Empress Matilda. During the lifetime of Henry I – Matilda’s father and Stephen’s uncle – Stephen had twice sworn oaths to guarantee the succession for Matilda. But when the time came, when Henry died on 1 December 1135, Stephen broke those oaths, and had himself crowned king in Westminster Abbey just 3 weeks after his uncle’s death.

If he thought Matilda would just accept losing her crown and stay at home with the children, Stephen was sorely mistaken. Pregnant with her third child at the time of her father’s death, Matilda had to bide her time, for a little while. And, as her husband Geoffrey of Anjou campaigned on her behalf in Normandy, Matilda landed in England on 30 September 1139 and her own campaign to claim the crown began.

And she nearly won.

The First Battle of Lincoln

Early in 1141, news reached King Stephen that Ranulf de Gernons, the disgruntled Earl of Chester, had captured Lincoln Castle. Disappointed in his aspirations to Carlisle and Cumberland after they were given to Prince Henry of Scotland, Ranulf had turned his sights on Lincoln Castle, which had once been held by his mother, Lucy of Bolingbroke, Countess of Chester. Countess Lucy had died around 1138, leaving her Lincolnshire lands to her son by her second marriage, William de Roumare, Ranulf’s half-brother. Her lands elsewhere had been left to Ranulf de Gernons, who was the son of her third marriage, to Ranulf le Meschin, Earl of Chester.

It seems that in late 1140 Ranulf and his brother had contrived to gain possession of Lincoln Castle by subterfuge. As the story goes, the two brothers waited until the castle garrison had gone hunting before sending their wives to visit the castellan’s wife. A short while after, Earl Ranulf appeared at the castle gates, wearing no armour and with only three attendants, supposedly to collect his wife and sister-in-law. Once allowed inside, he and his men overpowered the small number of men-at-arms left to guard the castle and opened the gates to his brother. The half-brothers took control of the castle and, with it, the city of Lincoln.

The citizens of Lincoln appealed to the king, who had promptly arrived outside the castle walls by 6 January 1141 and began his siege. Earl Ranulf somehow escaped from the castle and returned to his lands in Chester in order to raise more troops. He also took the opportunity to appeal to his father-in-law for aid. Ranulf’s father-in-law was, Robert, Earl of Gloucester, the illegitimate son of Henry I and brother of Empress Matilda. A very capable soldier, Earl Robert commanded Matilda’s military forces and his daughter, Maud of Gloucester – Ranulf’s wife – was still trapped inside Lincoln Castle. If the need to rescue his daughter was not enough motivation to persuade Robert to intercede at Lincoln, Ranulf also promised to switch his allegiance, and his considerable resources, to Empress Matilda. Robert marched to Lincoln, meeting up with his son-in-law along the way. The earls’ forces arrived on the outskirts of Lincoln on 1 February, crossed the Fossdyke and the River Witham and arrayed for battle. Their rapid approach caught Stephen unawares. Outnumbered, Stephen was advised to withdraw his forces, until he could muster enough men to make an even fight of it.

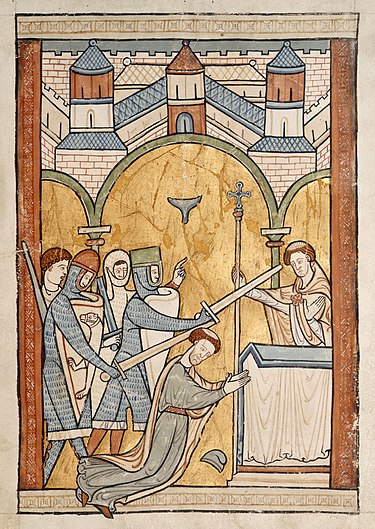

Stephen, perhaps remembering the destruction of his father’s reputation after his flight from Antioch, refused to withdraw. He would stand and fight. The next morning, 2 February 1141, before battle was joined, King Stephen attended a solemn mass in the cathedral; according to Henry of Huntingdon, who claimed Bishop Alexander of Lincoln as his patron and may well have been present, the service was replete with ill omens:

‘But when, following custom, he offered a candle fit for a king and was putting it into Bishop Alexander’s hands, it broke into pieces. This was a warning to the king that he would be crushed. In the bishop’s presence, too, the pyx above the altar, which contained the Lord’s Body, fell, its chain having snapped off. This was a sign of the king’s downfall.’

Henry of Huntingdon, The History of the English People 1000-1154

After mass, the king led his forces through Lincoln’s West Gate, deploying them either on the slope leading down to the Fossdyke or possibly at the bottom of the slope, on Carrholme. King Stephen formed his army into three divisions, with mounted troops on each flank and the infantry in the centre. On the right flank were the forces of Waleran de Meulan, William de Warenne, Simon de Senlis, Gilbert of Hertford, Alan of Richmond and Hugh Bigod, Earl of Norfolk. The left was commanded by William of Aumale and William of Ypres, Stephen’s trusted mercenary captain, who led a force of Flemish and Breton troops. The centre comprised the shire levy, which included citizens of Lincoln, and Stephen’s own men-at-arms, fighting on foot around the royal standard.

The opposing army also deployed in three divisions, with ‘the disinherited’, those deprived of their lands by King Stephen, on the left. The infantry, comprising of Earl Ranulf’s Cheshire tenants and other levies, and dismounted knights were in the centre under Earl Ranulf himself. The cavalry, under the command of Earl Robert of Gloucester formed the right flank. The Welsh mercenaries, ‘ill armed but full of spirits’ were arrayed on the wings of the army. Before the battle, Henry of Huntingdon reports, speeches were heard from both sides, exhorting the men to battle and insulting the opposing commanders.

Baldwin fitz Gilbert spoke for King Stephen, whose voice did not carry well. According to Henry of Huntingdon, the armies were mobilising before his speech ended. The rebels were the first to advance, ‘the shouts of the advancing enemy were heard, mingled with the blasts of their trumpets, and the trampling of the horses, making the ground to quake.’ The ranks of the ‘disinherited’ moved forward with swords drawn, rather than lowered lances, intent on close quarter combat. This left flank of the rebel army fell upon Stephen’s right flank, ‘in which were Earl Alan, the Earl of Mellent [Meulan], with Hugh, the Earl of East Anglia [Norfolk], and Earl Symon, and the Earl of Warenne, with so much impetuosity that it was routed in the twinkling of an eye, one part being slain, another taken prisoner and the third put to flight.’ Faced with the ferocity of the assault and the very real prospect of death, rather than being taken prisoner and held for ransom, the earls fled the field with the remnants of their men. It was every man for himself as Stephen’s right wing disintegrated in panic.2

The left wing of the royal army appeared to have greater success, at least initially. The men of William of Aumale, Earl of York and Stephen’s mercenary captain, William of Ypres, rode down the Earl of Chester’s Welsh mercenaries and sent them running, but ‘the followers of the Earl of Chester attacked this body of horse, and it was scattered in a moment like the rest.’3 Other sources suggest that William of Ypres and William of Aumale fled before coming to close quarters with the enemy.4 Either way, William of Ypres’ men were routed and he was in no position to support the king and so fled the field, no doubt aware that he would not be well-treated were he to be captured.

Stephen’s centre, the infantry, including the Lincolnshire levies and the king’s own men-at-arms, were left isolated and surrounded, but continued to fight. Stephen himself was prominent in the vicious hand-to-hand fighting that followed. Henry of Huntingdon vividly describes the desperate scene as ‘the battle raged terribly round this circle; helmets and swords gleamed as they clashed, and the fearful screams and shouts re-echoed from the neighbouring hill and city walls.’5 The rebel cavalry charged into the royal forces killing many, trampling others and capturing some. King Stephen was deep in the midst of the fighting:

‘No respite, no breathing time was allowed, except in the quarter in which the king himself had taken his stand, where the assailants recoiled from the unmatched force of his terrible arm. The Earl of Chester seeing this, and envious of the glory the king was gaining, threw himself upon him with the whole weight of his men-at-arms. Even then the king’s courage did not fail, but his heavy battle-axe gleamed like lightning, striking down some, bearing back others. At length it was shattered by repeated blows, then he drew his well-tried sword, with which he wrought wonders until that, too, was broken.’

Henry of Huntingdon, The History of the English People 1000-1154;

According to Orderic Vitalis and the Gesta Stephani, it was the king’s sword that broke first, before he was passed a battle-axe by one of the fighting citizens of Lincoln, in order to continue the fight. Whatever the order, the king’s weapons were now useless and the king ‘fell to the ground by a blow from a stone.’6 Stephen was stunned and a soldier named William de Cahaignes then rushed at him, seized him by his helmet and shouted, ‘Here! Here! I have taken the king!’

The king’s forces being completely surrounded, flight was impossible. All were killed or taken prisoner, including Baldwin fitz Gilbert, the man who had given the rousing pre-battle speech to the men. In the immediate aftermath of the fighting, Lincoln was sacked, buildings set alight, valuables pillaged, and its citizens slaughtered by the victorious rebels.

Lady of the English

Defeated, Stephen was first taken to Empress Matilda and then to imprisonment at Bristol Castle. A victorious Matilda was recognised as sovereign by the English people.

As for Matilda, ‘the lady empress-queen, Henry’s daughter, who was staying at Gloucester, was overjoyed at this event, having now, as it appeared to her, got possession of the kingdom for which fealty had been sworn to her’. As the Gesta Stephani, always insistent on naming Matilda countess rather than empress,relates, ‘the greater part of the kingdom at once submitted to the countess and her adherents and some of the king’s men, involved in sudden disasters, were being either captured or forcibly expelled from their possessions; others, very quickly foreswearing the faith they owed to the king, were voluntarily surrendering themselves and what was theirs to the countess’.

A victorious Matilda was recognised as sovereign by the English people, being named Lady of the English as Winchester in March.

Queen Matilda

And Stephen’s greatest asset now showed her mettle.

In April, Stephen’s wife, Queen Matilda, sent a letter that was read out at the Legatine Council in Winchester, presided over by Henry of Blois, papal legate and Bishop of Winchester – and brother of King Stephen. The queen pleaded with the clergy to release the king from his imprisonment and restore him to the throne. As may have been expected, Bishop Henry refused to give in to the queen’s request, but her pleas may have affected a delegation of Londoners, also present, who were still openly loyal to Stephen and would see Queen Matilda’s letter as encouragement for them to maintain their position in the face of the bishop’s persuasion. Clearly the empress had a long way to go before the Londoners would admit her into the capital for her coronation at Westminster Abbey.

However, by mid-June, the empress was at Westminster, outside the city walls of London.

Empress Matilda was now at the height of her success. Her rival was in her custody, the church was on her side, she had the keys to the royal treasury and was about to make a ceremonial entry into London, her capital: ‘The empress, as we have already said, having treated with the Londoners, lost no time in entering the city with a great attendance of bishops and nobles: and being received at Westminster with a magnificent procession, took up her abode there for some days to set in order the affairs of the kingdom.’ Her uncle David, King of Scots and her half-brothers Robert of Gloucester and Reginald de Dunstanville, now Earl of Cornwall, were by her side.

Empress versus Queen

With her husband held in chains in Bristol castle, Matilda of Boulogne, Queen of England, wife of King Stephen and cousin of Empress Matilda, stepped into the fight. She first tried to negotiate, offering to take Stephen into exile if Matilda would at least guarantee their son’s inheritance of their ancestral lands. The empress refused, perhaps remembering that no such guarantee was ever made to her son, Henry, dispossessed of his inheritance by Stephen’s usurpation of the crown. Undeterred, Queen Matilda established a secure base in Kent, from where she raised an army to march on London, burning and ravaging the countryside surrounding the capital. It was becoming apparent that the struggle was far from over. A final masterstroke was when she moved up William of Ypres and his Flemish mercenaries, to threaten London, thus inducing the Londoners to turn against the empress.

Henry, Bishop of Winchester, deserted the empress and joined the queen, promising to expend his efforts on obtaining the release of the king, his brother.

The empress’s success was turning sour.

On the eve of the empress’s ceremonial entrance into the capital, the city’s church bells rang out, a prearranged signal for the citizens to rise against the empress and open the gates to the queen’s approaching army. Empress Matilda was still at Westminster, ‘reclining at a well-cooked feast’. Westminster was an unfortified palace that was not easily defensible and ‘being, however, forewarned by some of them, she fled shamefully with her retinue, leaving all her own and their apparel behind’.

The empress had no choice. She and her supporters rode for Oxford. Although things appeared precarious, all was not lost. Queen Matilda now held London, but the empress still had Stephen in her custody and room for manoeuvre. By the end of July, the empress and her army were riding south. As she approached Winchester, the empress sent a request to Bishop Henry to meet her outside the city, at which point he promptly fled to join Queen Matilda at Guildford.

The Rout of Winchester

Winchester had two castles: the royal castle, which held for the empress, and Wolvesey, a palatial castle in the south-eastern corner of the city that was the residence of Bishop Henry of Winchester, though he was not at home at the time. Empress Matilda arrived at the royal castle of Winchester on 31 July and began the siege of Wolvesey on 1 August 1141.

In defiance, the garrison of the bishop’s castle threw burning material from the ramparts which, in the summer heat, quickly set the whole city ablaze. The stone cathedral survived, but much of the town, built in wood with thatched roofs, was lost. The devastation meant the city’s population had lost their homes and livelihoods, and the empress’s army were deprived of shelter and provisions. Worse, Queen Matilda was now approaching with an army of her own and, in turn, besieged the empress.

The empress’s army was trapped.

Surrounded, with the city in flames and supplies running short, the empress was forced to flee for her life. In the retreat, her half-brother and leading general, Robert, Earl of Gloucester, was captured.

Queen Matilda now had her own bargaining chip. As much as she needed her husband returned to her, the empress needed her brother.

Prisoner Exchange

The practical arrangements for the exchange were rather complicated, with neither side trusting the other to hold to the bargain. On 1 November 1141, Queen Matilda surrendered at Bristol Castle, with one of her sons and two unidentified magnates, so that Stephen could be set at liberty. The king then rode to Winchester, where Earl Robert had been taken under guard, and on his arrival on 3 November the earl was freed, leaving his eldest son and heir, William of Gloucester, as surety. When the earl reached Bristol, the queen, her son and the two unnamed magnates were set at liberty and returned to Winchester. At that point, William of Gloucester was freed as well. After nine months of harsh imprisonment, Stephen was free at last.

By Christmas 1141, having endured nine months of incarceration, Stephen was back on his throne and celebrating the festive season at Canterbury, where he was symbolically re-crowned by the archbishop of Canterbury, with his queen by his side.

The empress was faced with the realisation of how close she had come to winning it all.

But lost.

At least she had her brother back and the fight was far from over.

The war would drag on until Stephen’s death in 1154, but the empress never came as close again to winning the crown. She eventually passed the baton to her son, Henry FitzEmpress, who would reign as Henry II. It was a kind of victory: it was her son who succeeded King Stephen rather than his own. Empress Matilda could ultimately claim victory as the crown returned to her line and that of her father, Henry I.

*

Images:

Courtesy of Wikipedia except Lincoln Castle and Oxford Castle which are ©SharonBennettConnolly FRHistS

Selected bibliography:

Gesta Stephani, translated by K. R. Potter; Henry of Huntingdon, The History of the English People 1000-1154; Marjorie Chibnall, The Empress Matilda: Queen Consort, Queen Mother and Lady of the English; Teresa Cole, The Anarchy: The Darkest Days of Medieval England; Catherine Hanley, Matilda: Empress, Queen, Warrior; Helen Castor, She-Wolves: The Women who Ruled England before Elizabeth; Robert Bartlett, England Under the Norman and Angevin Kings; J. Sharpe (trans.), The History of the Kings of England and of his Own Times by William Malmesbury; Orderici Vitalis, Historiae ecclesiasticae libri tredecem, translated by Auguste Le Prévost; Chronicles of the Reigns of Stephen, Henry II and Richard I; Edmund King, King Stephen; Donald Matthew, King Stephen; Matthew Lewis, Stephen and Matilda’s Civil War: Cousins of Anarchy.

*

My Books:

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

Out Now! Women of the Anarchy

Two cousins. On the one side is Empress Matilda, or Maud. The sole surviving legitimate child of Henry I, she is fighting for her birthright and that of her children. On the other side is her cousin, Queen Matilda, supporting her husband, King Stephen, and fighting to see her own son inherit the English crown. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how these women, unable to wield a sword, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It show how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other.

Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK.

Coming on 15 June 2024: Heroines of the Tudor World

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. These are the women who made a difference, who influenced countries, kings and the Reformation. In the era dominated by the Renaissance and Reformation, Heroines of the Tudor World examines the threats and challenges faced by the women of the era, and how they overcame them. From writers to regents, from nuns to queens, Heroines of the Tudor World shines the spotlight on the women helped to shape Early Modern Europe.

Heroines of the Tudor World is now available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK.

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. It is is available from King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops or direct from Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon. Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org.

Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell and Elizabeth Chadwick, and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

*

©2024 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS