To many noble women, the religious life was a career that had been decided for them by their parents when they were still children, as with Mary of Blois. However, for some, this did not necessarily mean they spent their entire lives in the seclusion of the convent. This was the certainly case with Princess Mary, daughter of Edward I and Eleanor of Castile.

Mary of Woodstock was born on 11 or 12 March 1279, the 6th daughter of King Edward and Queen Eleanor. Edward and Eleanor were quite a nomadic couple, travelling among their domains, so their children were raised in the royal nursery, based largely at the royal palaces of Woodstock and Windsor; visits from their parents were quite infrequent and from Edward, their father, even less so.

Eleanor of Castile endured a remarkable number of pregnancies, the first was when she was about 13 or 14, resulting in a child who was stillborn or died shortly after birth. The fact that several children died before they reached adulthood has been suggested as a reason for her keeping her distance from her children when they were young; however, it is just as likely that the simple fact Edward and Eleanor ruled a vast kingdom, including their lands in France, meant their responsibilities necessitated long absences.

Eleanor’s almost-constant pregnancies, resulting in a total of sixteen children, meant there were regular additions to the nursery, which also housed a number of children from noble families, sent to be raised alongside the king’s children. Mary would have had many companions, including her brother Alphonso, who was heir to the throne and 5 years her senior, and her sister Margaret, who was 4 years older than Mary. She would be joined by another sister, Elizabeth of Rhuddlan, 3 years later.

In 1285, a year after the death of Prince Alphonso, the king took his family on a progress into Kent. Edward went on pilgrimage to the shrine of St Thomas Becket, at Canterbury, before spending a week at Leeds Castle with his family, followed by some hunting in Hampshire. It was at the end of this family holiday that they arrived at Amesbury priory in Wiltshire, where little Mary, still only 6 years old, was veiled as a nun; much to the delight of her grandmother, Eleanor of Provence, but to the consternation of her mother, the queen. Indeed, the Chronicle of Nicholas Trivet emphasises that Mary’s veiling was done by her father, at the request of her grandmother, but only with the ‘assent’ of her mother.1

It may well be that Eleanor had reservations about her daughter’s vocation being decided at such a young age, or that she feared it was only being done so Mary’s grandmother, Eleanor of Provence, would have a companion in the abbey. After a long and eventful life, and with her health failing, the dowager queen took her own vows at around the same time and retired to Amesbury Priory for her final years, dying there in June 1291. Mary’s veiling had been in the planning for some years; Edward I had been in correspondence with the abbey at Fontevrault, the mother house of Amesbury, since 1282, when the little princess was barely 3 years old.

Eleanor’s reluctance, therefore, was probably more to do with when Mary was to become a nun, rather than the vocation itself; after all, the conventual life was considered a good career for a noble lady. The timing of her veiling may have been advanced not only by the failing health of Eleanor of Provence, but also by the imminent departure of Mary’s parents. Edward and Eleanor were about to embark for the Continent and were expecting to be in France for a considerable time, years rather than months.

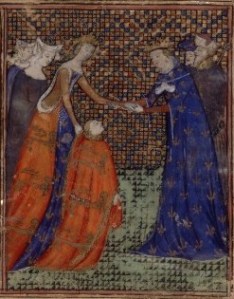

The actual veiling ceremony must have been very moving. It took place at Amesbury Abbey on 15 August 1285, where Mary was one of 14 high-born girls who took their vows together. It may well be that her cousin, Eleanor of Brittany – another granddaughter of Eleanor of Provence – took her vows at the same time; Eleanor would later demonstrate a great dedication to the religious life and, eventually, become Abbess of Fontevrault.

Mary’s life at the abbey was probably a very comfortable existence; in the year she was veiled, Mary was awarded an annual income of £100, rising to £200 a year in 1292, following the death of Eleanor of Provence. As she was still only a child, the nuns at Amesbury would have been responsible not only for Mary’s spiritual life, but also for her education. However, the cloistered life by no means meant that Mary was confined and separated from her family for any length of time. She made frequent visits to court throughout her life, and was present for most family occasions.

Having taken the veil in August 1285, Mary returned to be with her family in the autumn, to see the unveiling of the newly created Winchester Round Table and the creation of 44 new knights by her father, the king. She visited her family again in March and May of 1286, each visit lasting about a month. These visits also meant Mary had the chance to bid farewell to her parents, who departed for an extended stay in France in 1286. On 13 August 1289, Mary, her 4 sisters and little brother Edward were at Dover to welcome their parents home, after a 3-year absence.

Mary visited court again in 1290 and stayed for the wedding of her older sister, Joan of Acre, to Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester and Hertford; Joan and Gilbert were married in a private ceremony at Westminster on 30 April. It is likely that she was back at court later in the year for another wedding, this one at Westminster Abbey in July when her sister, Margaret, married John, the future Duke of Brabant.

Mary would have seen quite a lot of her parents in the spring of 1290 as her father chose Amesbury as the location for a special meeting, convened to settle the arrangements for the English succession. Edward may have chosen the abbey so that his ailing mother could be present for the discussions. The Archbishop of Canterbury and 5 other bishops, in addition to Edward, Eleanor of Castile and Eleanor of Provence, were all present to formalise the settling of the succession on Edward’s only surviving son, 6-year-old Edward of Caernarvon. Should Edward of Caernarvon die without heirs, it was decided that the succession would then pass to Edward I’s eldest daughter, the newly married Countess of Gloucester and Hereford, Joan of Acre.

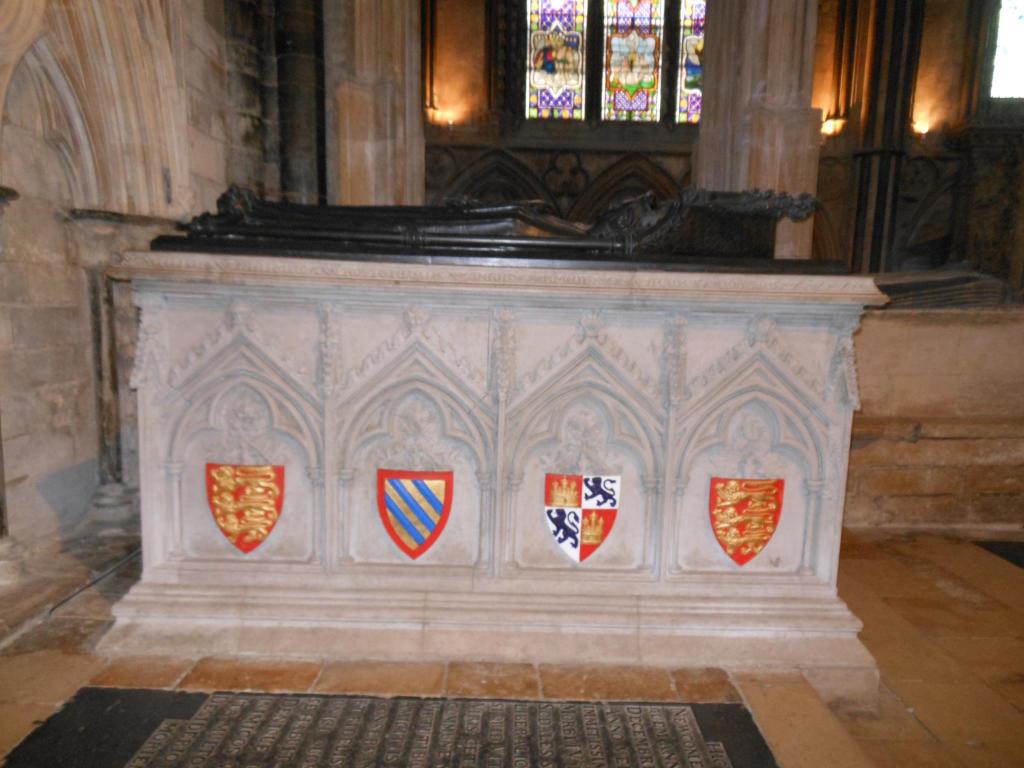

Eleanor of Castile was a distant mother when her children were young, but she seems to have developed closer relationships as they grew older, so it is not hard to imagine her taking the opportunity to spend time with 12-year-old Mary while they were staying at the abbey. It was probably one of the last times that Mary spent any real time with her mother, who died at Harby, near Lincoln, on 28 November 1290.

Indeed, it may well have been one of the last times they saw each other; Eleanor was at the king’s palace of Clipstone in Nottinghamshire when it was realised that her illness was probably fatal. Some of her children, Joan, Edward and Elizabeth, were summoned to the queen’s bedside; although Mary is not mentioned, it does not mean that she did not visit her mother one last time.2 Mary’s deep affection for her mother was demonstrated in 1297 when she and her younger sister, Elizabeth, jointly paid for a special Mass in their mother’s honour.

Mary’s career in the Church was far from spectacular; although her high birth gave her some influence, she never made high office and was never given a priory or abbey of her own. However, she was given custody of several aristocratic nuns at Amesbury, trusted to oversee their education and spiritual training. Convent life seems to have held few restrictions for her. Mary was regularly away from the cloister. She was frequently at court, or with various members of her family. In 1293 Mary spent time with her brother, Edward, and in 1297 she spent 5 weeks at court, taking the opportunity to spend some time with her sister, Elizabeth, who had been recently married to John, Count of Holland, and was preparing to join him there. In the event, news of John’s death arrived before her departure and Elizabeth never left England.

Mary had many cultural interests and was a patron of Nicholas Trivet, who dedicated his chronicle, Annales Sex Regum Angliae, to her. Mary was probably Trivet’s source for many of the details of Edward I’s family and the inclusion of several anecdotes that demonstrated Edward’s luck, such as the story of the king’s miraculous escape from a falling stone while sitting and playing chess. He had stood up to stretch his legs when the stone from the vaulted ceiling landed on the chair he had just vacated.3 The stories that Mary passed on to Trivet also serve to demonstrate that she was at court on a regular basis. The financial provisions settled on her by Edward I meant that Mary did not have to suffer from her vows of poverty.

In addition to the £200 a year she received from 1292, Mary was also granted 40 cocks a year from the royal forests and 20 tuns of wine from Southampton. In 1302, the provision was changed and she was given a number of manors and the borough of Wilton in lieu of the £200, but only for as long as she remained in England. Given that a proposed move to Fontevrault had been dropped shortly after the death of Eleanor of Provence, the likelihood of Mary leaving England seems to have been only a remote possibility.

Mary had a penchant for high living; she travelled to court with an entourage big enough to require 24 horses. By 1305, despite her income, she was substantially in debt, with the escheator south of the Trent being ordered to provide her with £200 in order to satisfy her creditors. Mary also had a taste for gambling, mainly at dice, and her father is known to have paid off at least one gambling debt.4 Following her father’s death in 1307, her younger brother, now King Edward II, continued to support Mary financially and she continued to make regular visits to court.

Mary died sometime around 1322 and was buried where she had lived, at Amesbury Priory. She was a princess whose future was decided for her at a very young age. She doesn’t seem to have excelled at the religious life, in that she never achieved significant office, but she did make the most of the life chosen for her, making frequent pilgrimages and taking charge of the young, aristocratic ladies who joined the convent. Despite her dedication to the Church, she found her own path within it and seems to have achieved a healthy (for her) balance between the cloister and the court.

There was, however, one moment of scandal; although it did not arise until more than 20 years after Mary’s death. In 1345, in a final, desperate attempt to escape an unhappy marriage John de Warenne, Earl of Surrey, claimed that he had had an affair with Mary and that, therefore, his marriage to her niece, Joan of Bar, was invalid due to the close blood relationship of the 2 women. Although it is highly unlikely that the claim was anything more than Surrey’s desperate attempt to find a way out of his marriage, it cannot be ignored that Mary was frequently at court and such an opportunity may have arisen; Mary was only a few years older than John de Warenne. The ecclesiastical court, however, refused to believe the earl’s claims and Mary’s reputation remains – largely – intact.

*

Footnotes:

1 Eleanor of Castile: The Shadow Queen by Sara Cockerill; 2 A Palace for Our Kings by James Wright; 3 Annales Sex Regum Angliae by Nicholas Trivet; 4 Eleanor of Castile: The Shadow Queen by Sara Cockerill

Images

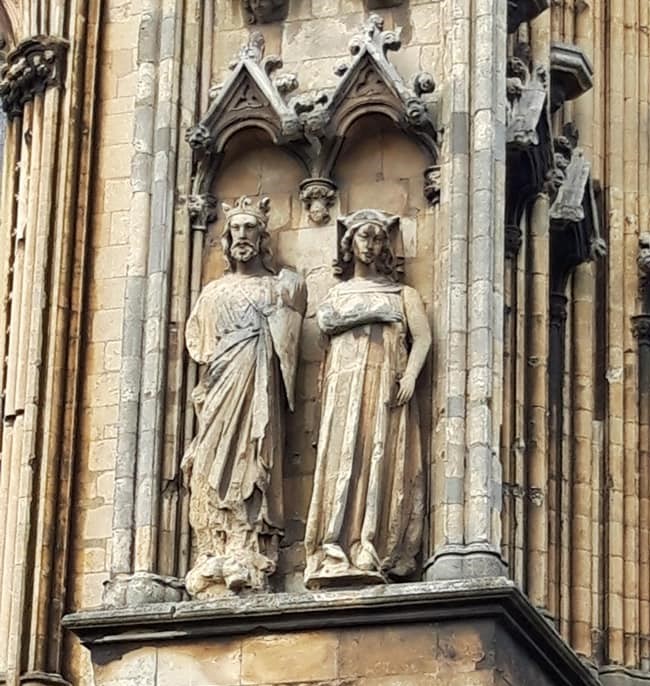

Courtesy of Wikipedia except the statues of Edward I and Eleanor of Castile and Eleanor’s viscera tomb at Lincoln Cathedral, which are ©2020 Sharon Bennett Connolly.

Sources:

Edward I A Great and Terrible King by Marc Morris; Brewer’s British Royalty by David Williamson; Britain’s Royal Families by Alison Weir; The Mammoth Book of British Kings & Queens by Mike Ashley; The Plantagenets, The Kings Who Made England by Dan Jones; OxfordDNB.com; findagrave.com; susanhigginbotham.com; womenshistory.about.com; Daughters of Chivalry by Kelcey Wilson-Lee; Nobility and Kingship in Medieval England by Andrew M. Spencer; Memoirs of the Ancient Earls of Warren and Surrey, and Their Descendants to the Present Time, Volumes I and II by Rev. John Watson; Eleanor of Castile: The Shadow Queen by Sara Cockerill; A Palace for Our Kings: The History and Archaeology of a Medieval Royal Palace in the Heart of Sherwood Forest by James Wright

My Books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available, please get in touch by completing the contact me form.

Coming 30 May 2023!

King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is now available for pre-order from Pen & Sword Books and Amazon UK. (I will hopefully have a US release date shortly)

In a time when men fought and women stayed home, Nicholaa de la Haye held Lincoln Castle against all-comers. Not once, but three times, earning herself the ironic praise that she acted ‘manfully’. Nicholaa gained prominence in the First Baron’s War, the civil war that followed the sealing of Magna Carta in 1215.

A truly remarkable lady, Nicholaa was the first woman to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Her strength and tenacity saved England at one of the lowest points in its history. Nicholaa de la Haye is one woman in English history whose story needs to be told…

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, of the successes and failures of one of the most powerful families in England, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Defenders of the Norman Crown: Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey is now available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, Bookshop.org and Book Depository.

Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, Bookshop.org and from Book Depository worldwide.

Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, Bookshop.org and from Book Depository worldwide.

Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, Bookshop.org and Book Depository.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

*

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

*

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

©2020 Sharon Bennett Connolly