As always, it is a pleasure to welcome my dear friend Toni Mount to History… the Interesting Bits. Toni has just written an informative and highly entertaining book, How to Survive in Tudor England, and she is here today to tell us about what went in to publishing a book in Tudor times.

Over to Toni…

Creating Books in the Sixteenth Century

I’ve been really busy this year, working on three books, all at the same time, each one at a different stage of production. I’m just completing the final proofs: text and images, and compiling the index for a popular history book – a fun guide to living in the Dark Ages – my next Sebastian Foxley medieval murder mystery is with the publisher and a third book is being researched. With so much scribing and checking going on, I thought this would be an opportunity to think about how my experiences of writing, printing and publishing might compare to those of a sixteenth-century author. What sort of books would they write? How would they write them? What were the new requirements of the printing press as opposed to books written by hand?

What sort of books would they write?

Some of the answers may surprise you. Religious subjects were to the fore around the time of the Reformation and would continue to be but self-help instruction books were extremely popular. Tales with a moral were reckoned most educational. History books tended to retell Classical events, such as the Siege of Troy, the founding of Rome and the Punic Wars fought between Romans and Carthaginians, as well as stories of the Roman emperors. The heroic exploits of Alexander the Great were retold as were those of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table in various guises. Science books were appearing too. With the advent of the printing press, scholarly treatises were no longer limited to a few hand-written copies but could be widely disseminated as printed editions. Since they were usually written in Latin as the universal language of academia and the Roman Catholic Church, they could be read – if not always understood – across Europe and the Americas. Novels, as such, were not yet recognised but obviously romantic stories of heroes and heroines, along with collections such as Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales and Boccaccio’s Decameron remained popular as ever. Poetry was also published.

One of the most popular religious books of the second half of the sixteenth century was Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. Originally published in London by John Day in 1563 under the title Actes and Monuments, it was written by John Foxe, a Protestant, giving an account of those who had suffered martyrdom at the hands of the Roman Catholic Church, particularly in England and Scotland, giving maximum coverage to those burnt at the stake during Mary Tudor’s reign. Now that Elizabeth was on the throne, the book became so popular it went through four editions and numerous reprints, including an abridged version known as the Book of Martyrs, before Foxe died in 1587. Long after his death, the book continued to influence anti-Catholic sentiments and was virtually compulsory reading for those of the Protestant faith in England.

Thomas Tusser [1524-80] was a farmer who fancied himself a poet. He wrote an instruction book for his fellow farmers – husbandmen – and their wives, all in rhyme. First published in 1557, A Hundreth Good Pointes of Husbandrie was enlarged and republished in 1573 as Five Hundred Points of Good Husbandry, being reprinted numerous times. It’s a fascinating book about country life and customs in the Tudor era and the source of information for some of my articles for this magazine. My favourite Tusser couplet is:

A respite to husbands the weather may send,

But housewife’s affairs have never an end.

How true.

Moral tales were regarded as educational and could also be fun to read. Aesop’s Fables were a perennial favourite, as were the adventures of Reynard the Fox, author unknown, but they date back to the eleventh century in France. The year 1481 saw the first printed edition of The History of Reynard the Fox to come from the Westminster press, just five years after William Caxton had set up the first ever printing business in England. Subsequent reprints appeared in 1489 and, after Caxton’s death, more were produced by Richard Pynson in 1494, 1500, 1506 and 1525. In fact, there were twenty-three editions of Reynard published in England in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, so Caxton had found a runaway bestseller.

Reynard, the anti-hero, relies on brains rather than brawn to get the better of his enemies, often having others do his dirty work. For example, in taking Tybert the Cat to the farmer’s barn where he can feast on mice, Reynard is well aware of the trap set by the farmer to catch him, after he stole some hens recently. Of course, it’s Tybert who gets trapped. But the Fox’s cleverness extends to the subtleness of a lawyer and the honeyed tongue of a courtier, saying all the right things, not only arguing his way out of trouble but to promoting his own cause at the king’s court – lessons to be learned for the would-be courtier perhaps.

One of the first scientific books was written by Robert Recorde, a Welsh mathematician living in England. Recorde was the first ‘popular science’ writer and, although he knew Greek and Latin, he taught and wrote in English so anyone who was literate could understand his work. In 1542, his text book on arithmetic, The Grounde of Artes, first introduced the plus, minus and equals signs [+, -, =] that make the writing of equations so much quicker. He read Nicolaus Copernicus’ ground-breaking book De Revolutionibus, published in 1543, that put the Sun, not the Earth, at the centre of the universe for the first time. Recorde gave the theories a lot of thought, noting his favourable conclusions in The Castle of Knowledge, published in 1551, agreeing that the new ‘heliocentric’ universe fitted the calculations more nearly and made more sense. In 1551, he published The Pathway to Knowledge, the first geometry book in English.

Towards the end of the Tudor period, William Gilbert, a physician in London for many years who served as Queen Elizabeth’s doctor, spent much of his time studying rocks as England’s first geologist. He was particularly fascinated by ‘lodestones’ that occur naturally as permanent magnets. Gilbert published his discoveries in his book De Magnete [About Magnets] in 1600. The book, written in Latin, soon became the standard text on magnetic phenomena throughout Europe. In it, Gilbert discussed and disproved the folktales about lodestones – that their effect was reduced if diamonds or garlic were nearby and that they could cure headaches. He replaced such odd ideas with proper physical laws of magnetism: that the north and south poles of a magnet attract each other but like poles repel.

Poetry, often of epic lengths, was far more popular in Tudor times than with today’s audience. Whereas Thomas Tusser wrote his practical instruction book in rhyming couplets, Edmund Spenser’s epic in six books, The Faerie Queene, was very different, composed in ‘Spenserian stanzas’, a form the poet invented specially. The Faerie Queene is a romance, taking elements from Arthurian legend, including a female knight, The Roman de la Rose and other medieval sources. Yet Spenser explains that his epic poem is full of ‘allegorical devices’ and intended ‘to fashion a gentleman or noble person in virtuous and gentle discipline’, so this too is an instruction book of sorts. The author presented the first three books to Queen Elizabeth in 1589 and was rewarded by her majesty with the very decent pension of £50 a year for life, so it was well worth the effort. Whether the queen ever read it – or perhaps Spenser read excerpts aloud to the court – we don’t know but it’s quite widely read today, often being a ‘set book’ in schools.

How would they write them?

Throughout the Tudor period, as well as for centuries before and since, the original work would have to be written out in long hand with pen and ink, occasionally on parchment but increasingly on paper. It is actually easier to make corrections on parchment because the ink can be scraped off the surface layer but it’s far more difficult with paper because the ink soaks right in. All corrections, re-writes and edits had to be copied out again which makes me ever grateful for my computer. Love poems were often exquisitely written in the final version and given as gifts to the beloved. Surprisingly, the idea of the typewriter was thought up in the mid-seventeenth century when an anonymous Englishman applied for a patent for just such a machine, supplying a full description, drawings and diagrams of his invention. Nothing ever came of it at the time, as far as we know, but more recently, the device was constructed from the diagrams and it worked! What a boon that would have been to authors and poets.

With medieval manuscripts, all the text, any artwork, images or decoration would be done by hand on the page but, of course, the process had to be repeated for every subsequent copy. This meant each book was unique and expensive to produce so the spreading of ideas and knowledge was slow. The printing press, first invented in c.1440 by the German goldsmith, Johannes Gutenburg, and brought to England in 1476 by William Caxton [see above], made the mass production of books a possibility. Gutenburg also came up with the idea of making hundreds or even thousands of individual letters out of little squares of lead alloy – all reversed mirror images – and punctuation.

What were the new requirements of the printing press as opposed to books written by hand?

Just as today, the publisher/printer would require a perfect copy of the final manuscript of the book to work from. I simply attach my – hopefully – faultless final document to an email to the publisher and click ‘send’. The Tudor author would have taken his completed hand-written manuscript to the publisher, having kept at least one other perfect copy for himself, if he was wise. This was a good idea because a few manuscripts that were used as printers’ copies have survived to the present and they are scribbled with annotations and notes for the setting of the type and other parts of the process. The author’s pristine manuscript is gone forever if he didn’t have a second copy.

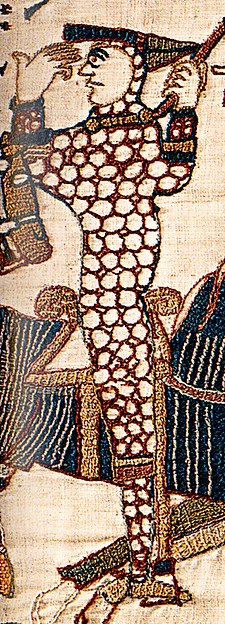

If illustrations are to be included in my books, I simple email a set of high resolution images, including photographs or downloaded pictures and diagrams. One thing I have to consider that a Tudor author wouldn’t need to bother about is the minefield of copyright on downloads. Early printed books – sometimes referred to as incunabulae – most often used woodcuts as a means of illustrating the text and the printer would have no qualms about using the same woodcut in a completely different work, if it served the purpose.

A Tudor printing press was a hefty machine, often taller than a man. Gutenburg had copied the idea from the grape presses used in wine-making. The tiny individual metal letters or ‘type’ were set up by a compositor, in reverse order, right to left, into the required lines of text. Several lines were arranged at once in a wooden frame known as a galley. Once the galleys were composed, they would be laid face up in a large frame [a forme] and this was placed onto a flat stone [the bed or coffin]. The text was then inked using two ball-shaped pads with handles. The balls were made of dog skin leather – because it has no pores – and stuffed with sheep’s wool. The ink was applied to the text evenly. A damp sheet of paper was held in one frame [the tympan] by small pins: damp so the type ‘bit’ into the paper better. The sheet was then sandwiched between the tympan and another paper- or parchment-covered frame [the frisket] to fix it so it could not move, curl up or wrinkle.

The two frames with their paper sandwiched were then lowered so the paper lay on the surface of the inked type. The whole bed was rolled under the platen using a handle to wind it into place. Then came the part of the process that required the most muscle power: screwing down the platen, using a bar called the ‘devil’s tail’, so the inked type and woodcuts pressed against the paper, making a perfect impression. The bar was supposed to spring back, lifting the platen, the bed rolled out, the frames lifted and the printed paper released, all text and images now appearing the right way round.

That would complete the process for a poster but, to make a book, this sheet of pages had to be turned over and printed again, this time with the text for the alternate pages. The sheets would then be cut up and assembled in the correct order. I have printed little eight-page booklets and the logistics of getting the double-sided pages printed correctly required a bit of thinking. For an A5 booklet, pages 8 and 1 have to be printed side by side, in that order, on an A4 sheet which is then turned over and pages 2 and 7 printed on the other side. Pages 6 and 3 are then printed with 4 and 5 on the reverse. I’m sure there must be computer algorithm for this these days but imagine trying to work that out with eight or sixteen pages on a sheet to produce the 1,500 pages of Foxe’s Book of Martyrs.

Foxe’s book had the additional complication of being illustrated with over sixty woodcut impressions and was, at the time, the most ambitious publishing project undertaken in England. Earlier, I mentioned that previous woodcuts were often reused but Foxe’s subject matter was entirely new so every woodcut was made especially. Like the type, woodcuts also had to be made as reverse images, carved from a single block of fine-grained wood. The image also had to be ‘negative’ in that the parts cut away would appear white on the page, the ink only adhering to the raised wood remaining to give the dark lines of the picture. When Foxe’s book was finished, compiled and bound, ready for sale, it was said to weigh as much as a small infant. Well, I always think of my books as my ‘babies’ and, even with modern technology, they take at least as long to produce, from conception until I hold the final product in my hands.

If you wish to read about many interesting characters, places, clothing, food and pastimes of the sixteenth century, my new book How to Survive in Tudor England is published on 30th October 2023.

About the book:

Imagine you were transported back in time to Tudor England and had to start a new life there, without smart phones, internet or social media. When transport means walking or, if you’re lucky, horse-back, how will you know where you are or where to go? Where will you live and where will you work? What will you eat and what shall you wear? And who can you turn to if you fall ill or are mugged in the street, or God-forbid if you upset the king? In a period when execution by be-heading was the fate of thousands how can you keep your head in Tudor England?

All these questions and many more are answered in this new guide book for time-travellers: How to Survive in Tudor England. A handy self-help guide with tips and suggestions to make your visit to the 16th century much more fun, this lively and engaging book will help the reader deal with the new experiences they may encounter and the problems that might occur.

Enjoy interviews with the celebrities of the day, and learn some new words to set the mood for your time-travelling adventure. Have an exciting visit but be sure to keep this book to hand.

About the author:

Toni Mount researches, teaches and writes about history. She is the author of several popular historical non-fiction books and writes regularly for various history magazines. As well as her weekly classes, Toni has created online courses for http://www.MedievalCourses.com and is the author of the popular Sebastian Foxley series of medieval murder mysteries. She’s a member of the Richard III Society’s Research Committee, a costumed interpreter and speaks often to groups and societies on a range of historical subjects. Toni has a Masters Degree in Medieval Medicine, Diplomas in Literature, Creative Writing, European Humanities and a PGCE. She lives in Kent, England with her husband.

*

My Books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

Out now: King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye

In a time when men fought and women stayed home, Nicholaa de la Haye held Lincoln Castle against all-comers, gaining prominence in the First Baron’s War, the civil war that followed the sealing of Magna Carta in 1215. A truly remarkable lady, Nicholaa was the first woman to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Her strength and tenacity saved England at one of the lowest points in its history. Nicholaa de la Haye is one woman in English history whose story needs to be told…

King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is now available from Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

Coming 15 January 2024: Women of the Anarchy

On the one side is Empress Matilda, or Maud. The sole surviving legitimate child of Henry I, she is fighting for her birthright and that of her children. On the other side is her cousin, Queen Matilda, supporting her husband, King Stephen, and fighting to see her own son inherit the English crown. Both women are granddaughters of St Margaret, Queen of Scotland and descendants of Alfred the Great of Wessex. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how these women, unable to wield a sword, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It show how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other.

Available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK.

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, of the successes and failures of one of the most powerful families in England, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Defenders of the Norman Crown: Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey is now available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org.

Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org.

Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org.

Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell, and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

©2023 Toni Mount and Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS