It is a pleasure to welcome novelist G.K. Holloway to History…the Interesting Bits today, to talk about the research behind his wonderful series The 1066 Saga.

Research for my books consists of mainly reading – books, magazines, academic papers, and blogs. It’s also good to get out a bit and visit and talking with experts, in my case locations of mainly locations of battles where I can talk with resident historians, reenactors and history fans, especially those with local knowledge.

Some of my reading consists of trawling around on the internet. It’s surprising what you can find, other than Wikipedia, as a source of material. And of course there are all sorts of groups on social media that specialise in my period in history. There are podcasts and blogs rich with information for recycling.

Books too, are an obvious place to look; the Doomsday Book is the first to spring to mind, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, and the Ecclesiastical History of Orderic Vitalis are useful too. But reader beware, it’s often the case with original material that objectivity wasn’t a strong point of the authors. Academic papers are nowadays can be easily accessed, although the cost of some of them is prohibitive. I’ve had read papers that have shone light into the dark recesses of history I hadn’t dreamed about. This means I’ll able to surprise readers with fascinating snippets that can give a glimpse of life a millennium ago.

Thank heavens for You Tube. There is a wealth of information to be found here, and a lot of it from top quality presenters and historians.

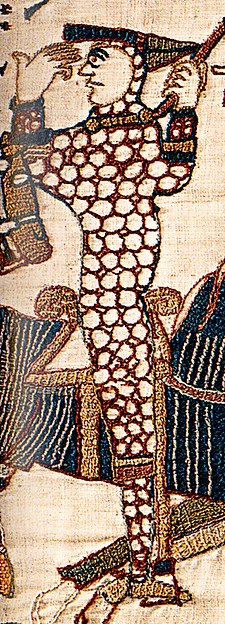

It’s not just what you see but what you don’t see that can be important. A prime example of this is the Bayeux Tapestry. It’s the closet you’ll get to newsreel footage of events covering the Norman Invasion. The full horror of war is not shied away from, burning houses, screaming women, decapitated soldiers and a horse running amok amongst dead bodies, all in glorious colour. But just as in modern times, news can be censored and people and events can be ’air brushed’ out of history, so too, it was the case way back then.

What remains of the well preserved embroidery, that’s correct, it is not a tapestry, is a sight to behold and worth a visit to Normandy to see. It’s surprising how colourful it is even after almost a thousand years. The imagery is clear and easy to follow but some scenes are missing. The story is told accurately enough and details like the appearance of Halley’s Comet are included. However, the Battle of Stamford Bridge is nowhere to be seen. Could it be that King William didn’t want it know that the army he fought at Senlac was exhausted from several hundred miles of marching and a huge battle against the biggest Norse army ever to have set foot in England. There is no depiction of the Battle of London Bridge, or the violence committed by his rampaging troops during his coronation. History has been, ‘cleaned up a bit,’ to the advantage of the victors. Nothing new there then.

It’s always a good idea to visit key locations. It’s one thing to look at maps and photographs but when you find yourself looking across the lagoons at Bosham, wandering around the castle at Falaise, starring up at Clifford’s Tower in York, or watching a reenactment at Battle Abbey, a much more realistic picture forms in your mind about what it must have been like to live all that time ago. To boost one’s knowledge it’s always a good idea to talk to reenactors; most of them have an encyclopaedic knowledge of the time period and especially their character’s part in it. Whether it be as a soldier, arrowsmith or seamstress.

Doing all the above is a great way of researching the history, but if like me, you write historical fiction rather than non-fiction, you would do well to read a good book. One I could recommend if, Story by Robert McKee. He deals with scriptwriting but it’s quite easy to apply his ideas to novels. You could also spend a lot of money and quite a bit of time on a creative writing course, but you might be better off getting a good editor.

So there you have it. Use as many sources as you can, and you’ll find many a nugget amongst the raw material.

1066: What Fates Impose

England is in crisis. King Edward has no heir and promises never to produce one. There are no obvious successors available to replace him, but quite a few claimants are eager to take the crown. While power struggles break out between the various factions at court, enemies abroad plot to make England their own. There are raids across the borders with Wales and Scotland.

Harold Godwinson, Earl of Wessex, is seen by many as the one man who can bring stability to the kingdom. He has powerful friends and two women who love him, but he has enemies will stop at nothing to gain power. As 1066 begins, England heads for an uncertain future. It seems even the heavens are against Harold.

In the Shadows of Castles

It’s the 1060s, and William of Normandy is establishing a new and brutal regime in England, but there are those who would defy him. As Norman soldiers spread like a plague across the land, resistance builds, but will it be enough to topple William and restore the rightful king to his throne? The English have the courage to fight, but the Normans, already victorious at Hastings, now build castles seeking to secure their tenuous foothold in these lands.

And what of the people caught up in these catastrophic events? Dispossessed but not defeated, their lives ripped apart, the English struggle for freedom from tyranny; amongst them, caught up in the turmoil, are a soldier, a thane and two sisters. As events unfold, their destinies become intertwined, bringing drastic changes that alter their lives forever.

Firmly embedded in the history of the Conquest, ‘In the Shadows of Castles’ is ultimately a story of love, hope and survival in a time of war.

About the Author:

1066 What Fates Impose, won the Gold Medal in the 2014 Wishing Shelf Independent Book Awards – Adult Fiction.

G K Holloway left university in 1980 with a degree in history and politics. After spending a year in Canada, he relocated to England’s West Country and began working in Secondary Education. Later he worked in Adult Education and then Further Education before finally working in Higher Education.

After reading a biography about Harold Godwinson, he became fascinated by the fall of Anglo Saxon England and spent several years researching events leading up to and beyond the Battle of Hastings. Eventually he decided he had enough material to make an engrossing novel. Using characters from the Bayeux Tapestry, the Norse Sagas, the Domesday Book and many other sources. He feels that he has brought the period and its characters to life in his own particular way. Following the major protagonists, as well as political, religious and personal themes, the downfall of Anglo-Saxon England is portrayed by a strong cast.

Nowadays he lives in Bristol with his wife and two children. When he’s not writing he works with his wife in their company.

1066 is his debut novel was originally published as an ebook. It has received very positive reviews and this has encouraged him to publish it in paperback. Currently he is working on a sequel. One day he hopes to write full time.

Visit G K Holloway’s website http://www.gkholloway.co.uk

GK Holloway’s books on Amazon

*

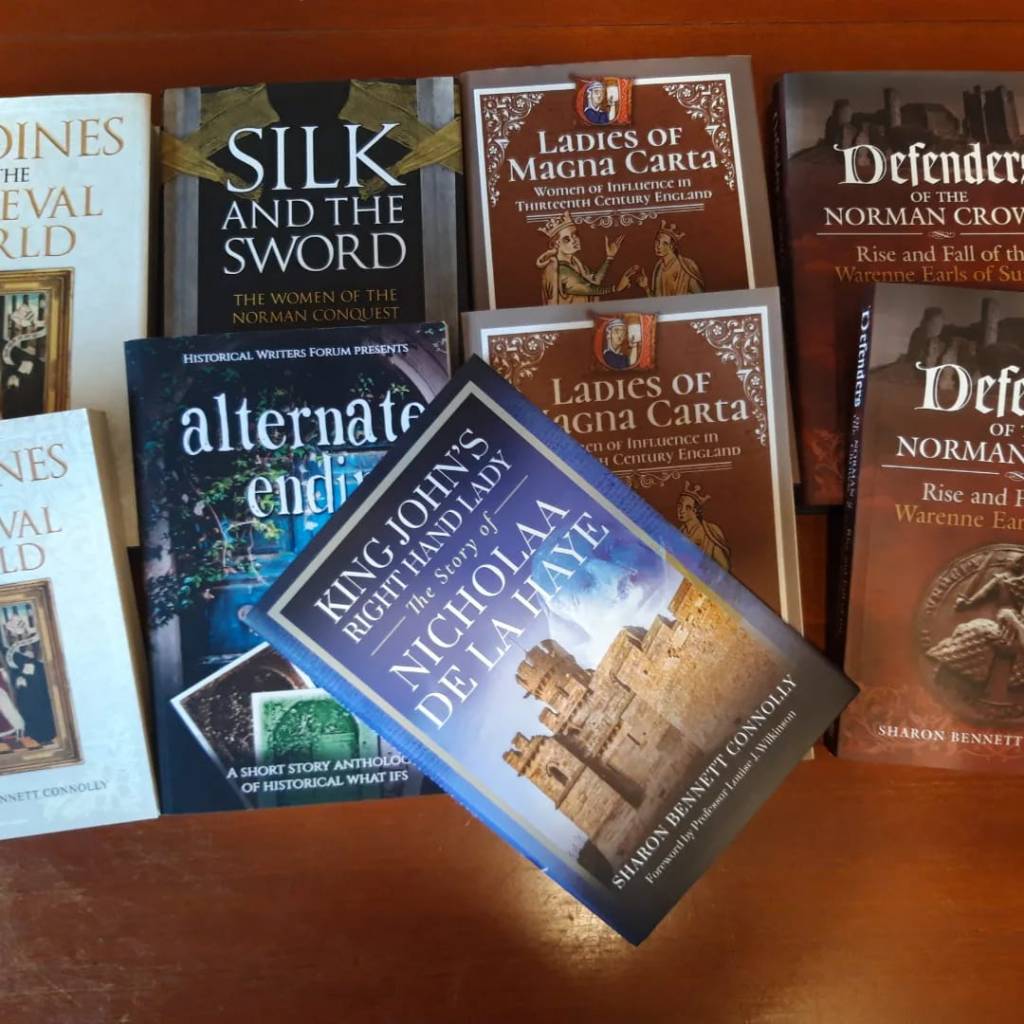

My Books:

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

Out Now! Women of the Anarchy

Two cousins. On the one side is Empress Matilda, or Maud. The sole surviving legitimate child of Henry I, she is fighting for her birthright and that of her children. On the other side is her cousin, Queen Matilda, supporting her husband, King Stephen, and fighting to see her own son inherit the English crown. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how these women, unable to wield a sword, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It show how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other.

Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK.

Coming on 15 June 2024: Heroines of the Tudor World

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. These are the women who made a difference, who influenced countries, kings and the Reformation. In the era dominated by the Renaissance and Reformation, Heroines of the Tudor World examines the threats and challenges faced by the women of the era, and how they overcame them. From writers to regents, from nuns to queens, Heroines of the Tudor World shines the spotlight on the women helped to shape Early Modern Europe.

Heroines of the Tudor World is now available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK.

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

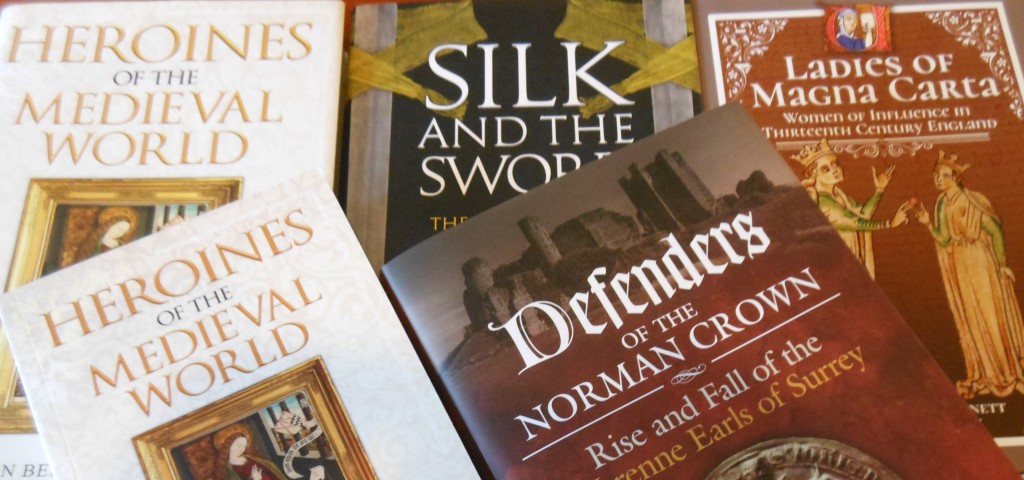

King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. It is is available from King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops or direct from Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon. Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org.

Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell and Elizabeth Chadwick, and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

*

©2024 GK Holloway and Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS.