In the reign of Edward I, when asked Quo Warranto ‘by what warrant he held his lands’ John de Warenne, the 6th earl of Surrey, is said to have drawn a rusty sword, claiming “My ancestors came with William the Bastard, and conquered their lands with the sword, and I will defend them with the sword against anyone wishing to seize them”

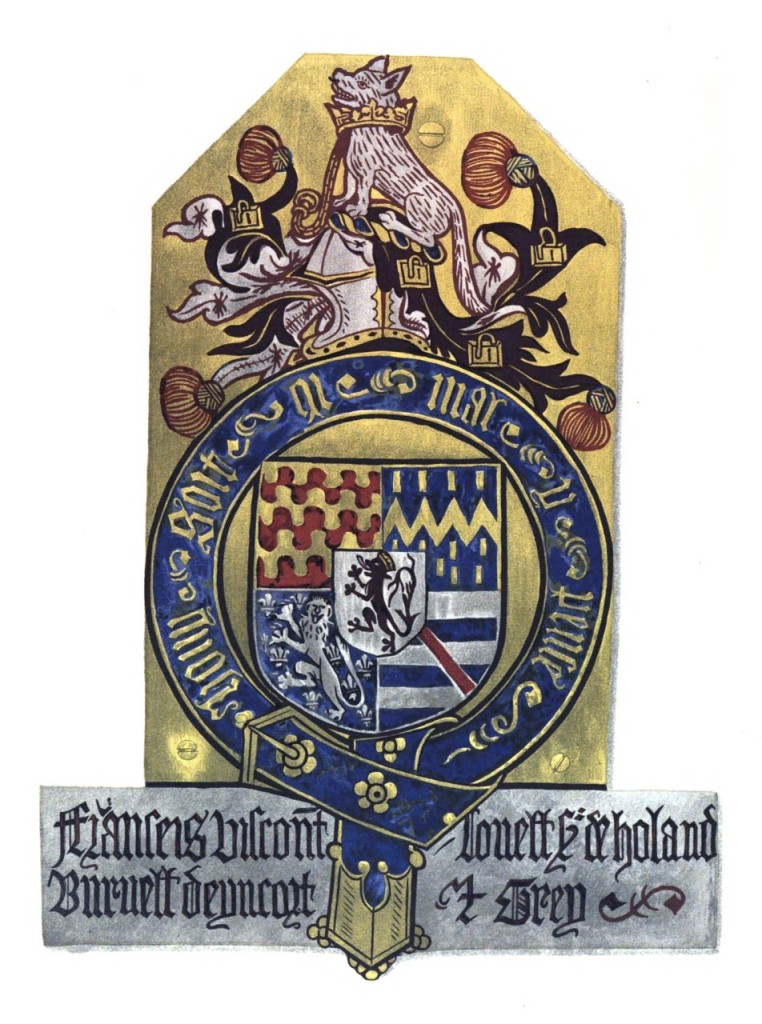

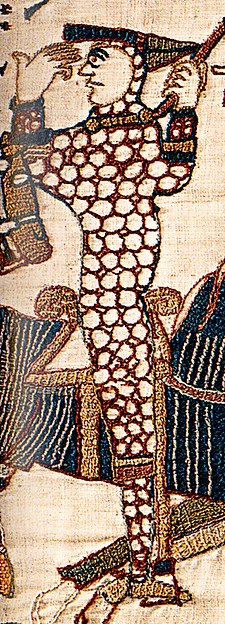

John’s ancestor, William de Warenne, 1st Earl of Surrey, fought for William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. He was rewarded with enough land to make him one of the richest men of all time.

In his search for a royal bride, the 2nd earl kidnapped the wife of a fellow baron.

The 3rd earl died on crusade, fighting for his royal cousin, Louis VII of France…

For three centuries, the Warennes were at the heart of English politics at the highest level, until one unhappy marriage brought an end to the dynasty. The family moved in the highest circles, married into royalty and were not immune to scandal. Defenders of the Norman Crown tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, of the successes and failures of one of the most powerful families in England, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III.

It’s finally here!

My fourth non-fiction book, Defenders of the Norman Crown: Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey, comes out today in hardback in the UK – it will be released in the US and elsewhere on 6 August. Telling the remarkable story of the Earls of Warenne and Surrey, and their family, from the time of the Norman Conquest to the reign of Edward III, Defenders of the Norman Crown follows a family right at the heart of Anglo-Norman England.

1 family. 8 earls. 300 years of English history!

And here’s what early reviewers are saying:

“Sharon Bennett Connolly has written an evocative narrative, highlighting the role the Warenne earls of Surrey played in the nation’s history. Her meticulous research is evident in every page, making the book both a reference guide and an immensely enjoyable read.“

Kristie Dean, author of On the Trail of the Yorks and The World of Richard III

Another great read from Pen & Sword. I’m vaguely familiar with this family, so reading a book specifically about their history from inception to the end of it, was very interesting. It’s definitely one I’d like to have on my shelf to reference again in the future.

NetGalley, Caidyn Young

5 out of 5 stars

An impressive and long overdue publication about the earls of Surrey, the Warenne (Varenne in Normandy) and their steadfast contributions and deep loyalties to the English Crown from the heyday of the Norman Conquest and the battlefield of Hastings to the glorious reign of Edward III. Ms. Bennett Connolly has given us a solidly researched portrait of a medieval family and its successful longevity during the three long and troublesome centuries that followed the Norman establishment on the throne and the roles played by its successive and prominent members in the shadows of the crown. A colorful tapestry through all the ups and downs of medieval England, its monarchical shenanigans and its military and political restlessness. Highly recommended to anyone interested in English and European medieval history.

NetGalley, jean luc estrella

Oh my goodness, Sharon Bennett Connolly has done it again! This was the perfect romp through a medieval family! Honor, scandal, marriages, and intrigue all play into the Warrene family lines.

Beginning with William of Normandy, and going down through the Wars of the Roses, this book will read as an action-packed, give me all the information book!I loved this one! The Warrene family was very prominent throughout the medieval history of England, and this book will dive into their past, and share everything that you could ever want to know about this ambitious family.

And if you would like to hear a little more about the Warenne earls, I presented the David Hey Memorial Lecture in 2020 as part of the Doncaster Local Heritage Festival. The lecture, Warenne: The Earls of Surrey and Conisbrough Castle, is still available to watch on YouTube.

Rebecca Hill, NetGalley

And …

To survive during the reigns of the Norman and Plantagenet Kings of England, one must understand where their loyalty and trust lied. Did they follow the crown or did they take a risk and follow those who opposed the person who wore the crown? For one family, there was no question who they were loyal to, which was the crown. The Warenne Earls of Surrey served the Kings of England from William the Conqueror to Edward III, gaining titles, prestige, and marriages that would cement their names in history books. They survived some of the most turbulent times in English history even if they did have a few scandals in their illustrious history. In Sharon Bennett Connolly’s latest non-fiction adventure, “Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rose and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey ”, she explores this family’s history that spanned over three centuries.

I would like to thank Pen and Sword Books and NetGalley for sending me a copy of this book. I have been a fan of Sharon Bennett Connolly’s books for a while now, so when I heard about this title, I knew I wanted to read it. I was going in a bit blind since I have never heard of the Warenne Earls of Surrey, but that is part of the fun of studying a new aspect of history.

The first Earl of Surrey, William de Warenne began this family’s tradition of royal loyalty as he joined William the Conqueror on his journey to England and fought alongside him to establish Norman rule at the Battle of Hastings. William’s descendants would be involved in some of the most important events of the time, from the crusades to the 1st and 2nd Baron’s Wars and the sealing of the Magna Carta. At some points, the earls would briefly switch sides if they thought the king was not in the best interest of the country, but they remained at the heart of English politics and worked hard to help guide the king and the country to become stronger.

What made the Warennes a tour de force when it came to noble families was their ability to marry well, except for the final earl and his scandalous relationships. The second earl desired to marry into the royal family, which did not happen, but his daughter, Ada de Warenne would marry William the Lion, King of Scotland. One of the daughters of Hamlin and Isabel de Warenne would be the mistress of King John and would give birth to his illegitimate son Richard of Chilham. The only woman of the family who inherited the earldom of Surrey, Isabel de Warenne, was married twice and so both of her husbands, William of Blois and Hamelin of Anjou, are considered the 4th earl of Surrey.

Connolly does a wonderful job explaining each story in de Warenne’s long history, including the minor branches of the family. I was able to understand the difference between family members who shared the same first name, (like William, John, and Isabel) but I know that others might have struggled with this aspect. I think it would have been helpful if Connolly had included either a family tree or a list of family members of the de Warennes at the beginning of this book to help readers who did struggle.

I found this particular title fascinating. The de Warenne’s were a family that proved loyalty to the crown and good marriages went a long way to cement one’s legacy in medieval England. Connolly proved that she has a passion for bringing obscure noble families to the spotlight through her impeccable research. If you want a nonfiction book of a noble family full of loyalty, love, and action, you should check out “Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey” by Sharon Bennett Connolly.

Heidi Malagisi, NetGalley and Adventures of a Tudor Nerd

David Hey Memorial Lecture

Last year, I presented the David Hey Memorial Lecture for Doncaster Heritage Festival, entitled Warenne: The Earls of Surrey and Conisbrough Castle. Just press play on the link below if you would like to watch and hear a little more about the Warennes.

Defenders of the Norman Crown: Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey is released in the UK today and in the US on 6 August. And it is now available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US and Book Depository.

Signed copies!

If you would like a signed, dedicated copy of Defenders of the Norman Crown: Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey, or any of my books, please get in touch by completing the contact me form.

Online Book Launch Event

Defenders of the Norman Crown online Book Launch!I am going to do a Zoom online talk to celebrate the launch of Defenders of the Norman Crown: Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey.It will be on Saturday 5th June from 7pm UK time, with a talk followed by a Q&A. Bring your own wine and cake!

If you would like to join me (please do!) then just pm me with your email address and I will send you an invite. If you would like to come along, please get in touch via the CONTACT ME form and I will send you an invite. Can’t wait to tell you all about Defenders of the Norman Crown and the Warenne earls of Surrey.

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available from Pen & Sword, Amazon and from Book Depository worldwide.

Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon and Book Depository.

Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, Book Depository.

*

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

*

Images: ©2021 Sharon Bennett Connolly

©2021 Sharon Bennett Connolly