Although the Battle of Hastings was fought by men, the women of the two opponents, Harold and William, had as much invested in the outcome as their husbands. The two women, however, have very different reputations. Whereas Matilda appears as the epitome of the medieval ideal woman, Edith has come down through history as ‘the other woman’. However, for both these women, their futures, and the futures of their children, were inextricably linked with the fates of the men fighting on Senlac Hill on that October morning in 1066.

Harold had met Edith Swan-neck at about the same time as he became earl of East Anglia, in 1044. Which makes it possible that Edith Swan-neck and the East Anglian magnate, Eadgifu the Fair, are one and the same. Eadgifu the Fair held over 270 hides of land and was one of the richest magnates in England. The majority of her estates lay in Cambridgeshire, but she also held land in Buckinghamshire, Hertfordshire, Essex and Suffolk; in the Domesday Book Eadgifu held the manor at Harkstead in Suffolk, which was attached to Harold’s manor of Brightlingsea in Essex and some of her Suffolk lands were tributary to Harold’s manor of East Bergholt. While it is by no means certain that Eadgifu is Edith Swan-neck several historians – including Ann Williams in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography – make convincing arguments that they were. Even their names, Eadgifu and Eadgyth, are so similar that the difference could be merely a matter of spelling or mistranslation; indeed, the abbey of St Benet of Hulme, Norfolk, remembers an Eadgifu Swanneshals among its patrons.

By 1065 Harold had been living with the wonderfully-named Eadgyth Swanneshals (Edith the Swan-neck) for twenty years. History books label her as Harold’s concubine, but Edith was, obviously, no weak and powerless peasant, so it’s highly likely they went through a hand-fasting ceremony – or ‘Danish marriage’ – a marriage, but not one recognized by the church, thus allowing Harold to take a second ‘wife’ should he need to. Harold and Edith had at least 6 children together; including four sons, Godwin, Edmund, Magnus and Ulf and two daughters, Gytha, who married Vladimir Monomakh, Great Prince of Kiev, and Gunnhild, was to become a nun at Wilton Abbey in Wiltshire, but never took her vows.

However, despite their twenty years and many children together, with the health of the king, Edward the Confessor, deteriorating, it became politically expedient for Harold to marry in order to strengthen his position as England’s premier earl and, possibly, next king. Ealdgyth was the daughter of Alfgar, earl of Mercia, and, according to William of Jumieges, very beautiful. She was the widow of Gruffudd ap Llywelyn, King of Gwynedd from 1039 and ruler of all Wales after 1055, with whom she had had at least one child, a daughter, Nest. Gruffudd had been murdered in 1063, following an expedition into Wales, some sources suggest it was by Harold himself, however Gruffudd’s own men are the chief suspects. Harold’s subsequent marriage to Ealdgyth not only secured the support of the earls of Northumbria and Mercia, but also weakened the political ties of the same earls with the new rulers of north Wales.

Rather than his loyal and loving ‘wife’, Edith, it was Ealdgyth, therefore, who was for a short time, queen of England. However, with Harold having to defend his realm, first against Harold Hardrada and his own brother, Tostig, at Stamford Bridge in September of 1066 and, subsequently, against William of Normandy at Hastings, it is unlikely Ealdgyth had time to enjoy her exalted status. At the time of the Battle of Hastings, 14th October 1066, Ealdgyth was in London, but her brothers took her north to Chester soon after. Although sources are confused it seems possible that Ealdgyth was heavily pregnant and gave birth to a son, Harold Haroldson, within months of the battle. Unfortunately, that is the last we hear of Ealdgyth; her fate remains unknown. Young Harold is said to have grown up in exile on the Continent and died in 1098.

Despite his marriage to Ealdgyth it seems Edith Swan-neck remained close to Harold and it was she who was waiting close by when the king faced William of Normandy at Senlac Hill near Hastings on 14th October 1066. She awaited the outcome alongside Harold’s mother, Gytha. Having lost a son, Tostig, just two weeks before, fighting against his brother and with the Norwegians at the Battle of Stamford Bridge, Gytha lost three more sons – Harold, Gyrth and Leofwine – and her grandson, Haakon, in the battle at Hastings.

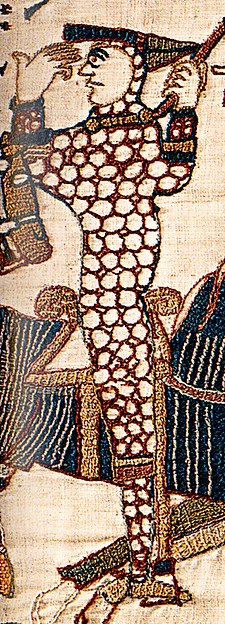

And it was Edith and the elderly Gytha, who wandered the blood-soaked field in the aftermath of the battle, in search of the fallen king. Sources say that Gytha was unable to identify her sons amidst the mangled and mutilated bodies. It fell to Edith to find Harold, by undoing the chain mail of the victims, in order to recognize certain identifying marks on the king’s body – probably tattoos.

The monks of Waltham Abbey had a tradition of Edith bringing Harold’s body to them for burial, soon after the battle. Although other sources suggest Harold was buried close to the battlefield, and without ceremony, it is hard not to hope that Edith was able to perform this last service for the king. However, any trace of Harold’s remains was swept away by Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries, so the grave of England’s last Anglo-Saxon king is lost to history.

Harold’s mother, Gytha, eventually fled into exile on the Continent, taking Harold and Edith’s daughter, another Gytha, with her, possibly arranging her marriage to the prince of Smolensk and – later – Kiev. The sons of Edith and Harold fled to Ireland with all but one, living into the 1080s, though the dates of their eventual deaths remain uncertain. Gunnhild remained in her nunnery at Wilton until sometime before 1093, when she became the wife or concubine of Alan the Red, a Norman magnate. Whether or not she was kidnapped seems to be in question but when Alan died in 1093, instead of returning to the convent, Gunnhild became the mistress of Alan’s brother and heir, Alan Niger. Alan Rufus held vast lands in East Anglia – lands that had once belonged to Eadgifu the Fair and, if Eadgifu was Edith Swan-neck, it’s possible that Alan married Gunnhild to strengthen his claims to her mother’s lands.

Of Edith Swan-neck, there is no trace after Harold is interred at Waltham Abbey, she simply disappears from the pages of history…

For Matilda, on the other hand, the Battle of Hastings marked the start of another stage of her life and career as the wife of William, duke of Normandy and, now, King of England. Matilda of Flanders was probably born around 1032, the daughter of Baldwin V, count of Flanders, and his wife, Adela, a daughter of King Robert the Pious of France. The young duke, William of Normandy, was probably pushing his luck when he proposed a marriage between himself and young Matilda. Although he was a duke and Baldwin a mere count, there was the question of his illegitimacy and Normandy was hardly the most stable of regions; William had spent all of his adult life fighting to keep hold of it.

A later story tells of how Matilda refused to marry William, stating that, being granddaughter of a king, she was too high born to marry a bastard. William was said to be so incensed with this response that he straightaway rode to Flanders, accosted young Matilda in the street, pulling her from her horse by her braids, before hitting her and cutting her with his spurs; whereupon Matilda changed her mind and agreed to marry William. While amusing, it is highly likely that the story is an invention, and highly unlikely that Matilda was asked her opinion on the marriage. Getting to the altar was not an easy task, however, as the pope refused to allow the marriage, without giving his reasons. It is possible that the refusal was on the grounds of consanguinity, although it seems the only familial link is that William’s aunt married Matilda’s grandfather as his second wife (Matilda’s father, however, was the son of the count’s first wife, so there was no blood relationship). It seems more likely that the refusal was politically motivated, due to Count Baldwin’s support of the Lotharingian’s rebellion against Pope Leo IX’s sponsor, the Holy Roman Emperor.

William was not to be thwarted, however, and before 1053 he married, Matilda despite the papal interdict; they were eventually ordered to establish a monastery each in penance for the marrying without papal dispensation, but the marriage was allowed to stand. In penance Matilda established the Abbaye-aux-Dames, consecrated in 1066, while William founded the Abbay-aux-Hommes, both in Caen.

The marriage between Matilda and William proved to be a strong and trusting relationship; William is one of very few medieval kings believed to have been completely faithful to his wife, no rumours of extra-marital affairs have ever been uncovered. He trusted Matilda to act as regent in Normandy during his many absences on campaign or in England. Matilda supported her husband’s proposed invasion of England, promised a great ship for William’s personal used, it was called the Mora; the ship had a figurehead of a small boy, whose right hand pointed to England and left hand held a horn to his lips.

Matilda and William had a rather large family, with 4 boys and at least 4 daughters. Their eldest son, Robert Curthose, who inherited Normandy, was followed by Richard, who was killed during a hunting accident as a youth, William, known as Rufus who became King William II, and the future Henry I. Of the 4 or 5 daughters Adelida became a nun following a series of failed marriage plans, Cecilia was given to the convent of Ste Trinite as a child, Constance married Alain Fergant, duke of Brittany and Adela married Stephen of Blois; their son, another Stephen would succeed Henry I as King of England. There are suggestions of 2 further daughters, Matilda and Agatha, though evidence for their existence is highly limited.

Matilda was very close to her family, especially her eldest son, Robert, whose later antics were to cause problems between his parents. William and Robert, father and son, were often at loggerheads, with Robert in open rebellion against his father as a young adult. Matilda was constantly trying to play the peacemaker and was so upset by one quarrel that she was ‘choked by tears and could not speak’. Even during a period of exile imposed on Robert, Matilda still supported her son as best she can; she would send him vast amounts of silver and gold through a Breton messenger, Samson. On discovering Samson’s complicity William threatened to blind the messenger and it was only through Matilda’s intervention that the Breton escaped.

Where poor Edith Swan-neck lost almost everything at Hastings, Matilda’s star was in the ascendant, but the Conquest was not without problems and it was not until 1068 that William felt secure enough to bring his wife over to England. Matilda was crowned Queen of England in Winchester Cathedral at Pentecost in that year, although further unrest soon saw her returned to the relative safety of Normandy, where she was acting as regent for her absent husband. Matilda was one of the most active of medieval queens, standing in as an able administrator during her husband’s absences; hearing land pleas and corresponding with such as the pope, who is known to have asked her to use her influence over her husband, on occasion. She was also the driving force in holding together her family, keeping relations as cordial as possible, even with the rebellious Robert. And it may well be her own strength of character, as the centre of the family, that meant none of her sons would marry until after her death.

Matilda’s piety is renowned. Although founding the Abbaye-aux-Dames in Caen was a penance for her irregular marriage to William, her constant and repeated donations to religious houses demonstrate her dedication to her faith. Among her many donations; she gave the monks of Marmoutier a new refectory and a cope and to the monks of St Evroult she gave £100 for a refectory, a mark of gold, a chasuble decorated with gold and pearls, and a cope for the chanter. The nuns of her abbey at Ste Trinite, Caen, received a substantial bequest from Matilda’s will; as well as her regalia, they were given a chalice, a chasuble, a mantle of brocade, 2 golden chains with a cross, a chain decorated with emblems for hanging a lamp in front of the altar, several large candelabras, the draperies for her horse and all the vases ‘which she had not yet handed out during her life’.

Matilda and William’s relationship is one of the most successful of the medieval period. Said to be a happy and loving marriage, their trust in each other was demonstrable and it was remarked up on when William fell seriously ill during a stay at Cherbourg between 1063 and 1066, Matilda prayed for his recovery at the altar; the monks remarking on her informal appearance as the sign of her distress her husband illness was causing her. Matilda fell ill in the late summer of 1083 and died on 2nd November of the same year. She was buried at Ste Trinite, Caen, where the original tombstone, with the inscription carved round the edge, still survives. Following her death William cut a sad and lonely figure; becoming increasingly isolated he followed his wife to the grave 4 years later in 1087.

Select bibliography:

Oxforddnb.com; The Norman Conquest: William the Conquerors’ Subjugation of England by Teresa Cole; William the Conqueror: The Bastard of Normandy by Peter Rex; Kings, Queens, Bones and Bastards by David Hilliam; Britains’ Royal Families: The Complete Genealogy by Alison Weir; The Oxford Companion to British History edited by John Cannon; epistolae.ccnmtl.columbia.edu.

My Books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

Out now: King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye

In a time when men fought and women stayed home, Nicholaa de la Haye held Lincoln Castle against all-comers, gaining prominence in the First Baron’s War, the civil war that followed the sealing of Magna Carta in 1215. A truly remarkable lady, Nicholaa was the first woman to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Her strength and tenacity saved England at one of the lowest points in its history. Nicholaa de la Haye is one woman in English history whose story needs to be told…

King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is now available from Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

Coming 15 January 2024: Women of the Anarchy

On the one side is Empress Matilda, or Maud. The sole surviving legitimate child of Henry I, she is fighting for her birthright and that of her children. On the other side is her cousin, Queen Matilda, supporting her husband, King Stephen, and fighting to see her own son inherit the English crown. Both women are granddaughters of St Margaret, Queen of Scotland and descendants of Alfred the Great of Wessex. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how these women, unable to wield a sword, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It show how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other.

Available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK.

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, of the successes and failures of one of the most powerful families in England, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Defenders of the Norman Crown: Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey is now available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org.

Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org.

Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org.

Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell, and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

©2023 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS