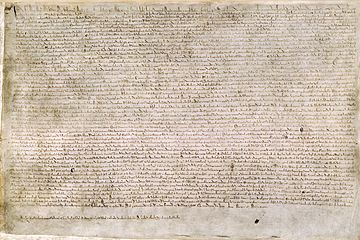

Other than the Queen of England, Isabelle d’Angoulême, only two women who can be clearly identified in Magna Carta itself. Though they are not mentioned by name, they are two Scottish princesses. The older sisters of King Alexander II had been held hostage in England since 1209, when John forced the humiliating Treaty of Norham on their ailing father, King William the Lion. Clause 59 of Magna Carta promised:

‘We will treat Alexander, king of Scots, concerning the return of his sisters and hostages and his liberties and rights in the same manner in which we will act towards our other barons of England, unless it ought to be otherwise because of the charters which we have from William his father, formerly king of Scots; and this shall be determined by the judgement of his peers in our court.’

Taken from Marc Morris, King John

The king of Scots’ two sisters referred to in the clause were Margaret and Isabella, the oldest daughters of William I (the Lion), King of Scots, and his wife, Ermengarde de Beaumont. The two girls had been caught up in the power struggle between their father and the Plantagenet kings. William I had been the second of three sons of Henry, Earl of Northumberland, and his wife, Ada de Warenne. He was, therefore, a grandson of David I and great-grandson of Malcolm III Canmor and St Margaret, the Anglo-Saxon princess. William had succeeded to his father’s earldom of Northumberland in June 1153, when his older brother, Malcolm IV, succeeded their grandfather as King of Scots. William himself became King of Scots on Malcolm’s death on 9 December 1165, aged about 23.

When William was looking for a wife, in 1186, King Henry II suggested Ermengarde de Beaumont, daughter of Richard, Vicomte de Beaumont-sur-Sarthe, and great-granddaughter of Henry I of England through one of the king’s many illegitimate offspring. With such diluted royal blood, she was hardly a prestigious match for the king of Scots, but he reluctantly accepted the marriage after consulting his advisers. The wedding took place at Woodstock on 5 September 1186, with King Henry hosting four days of festivities and Edinburgh Castle was returned to the Scots as part of Ermengarde’s dowry.

After the wedding, King William accompanied King Henry to Marlborough whilst the new Scottish queen was escorted to her new home by Jocelin, Bishop of Glasgow, and other Scottish nobles. Before 1195 Queen Ermengarde gave birth to two daughters, Margaret and Isabella. A son, the future Alexander II, was finally born at Haddington on 24 August 1198, the first legitimate son born to a reigning Scottish king in seventy years; a contemporary remarked that ‘many rejoiced at his birth.’1 A third daughter, Marjorie, was born sometime later.

Margaret, the eldest daughter of William I and Ermengarde de Beaumont, had been born sometime between her parents’ marriage in 1186 and 1195, unfortunately we cannot be more specific. Given the apparent youth of Ermengarde on her wedding day, Margaret’s date of birth is more likely to have been 1190 or later. We do know that she was born by 1195, as she was mooted as a possible heir to King William I in the succession crisis of that year, when the king fell gravely ill. Primogeniture was not yet the established order of succession, nor was the idea of a female ruler a welcome one; the period known to history as the Anarchy, which followed King Stephen’s usurpation of the throne from Empress Matilda, would have still been fresh in people’s memories, even in Scotland. King David had, after all, supported his niece’s claims against those of her cousin. The lesson of 20 years of civil war, albeit over the border, would have given William’s counsellors pause for thought in their own succession issue.

Several options were proposed at the time, including marrying young Margaret to Otto of Saxony, son of Henry II’s eldest daughter Matilda and nephew of King Richard I. However, it was also proposed that Margaret should not even be considered as heir, that the kingdom should pass to her father’s younger brother, David. In the event, King William recovered and none of the options were pursued, but at least it means that we know Margaret was born before 1195. And when her brother, Alexander, was born in 1198, Margaret’s position as a possible heir was diminished further.

Margaret’s younger sister, Isabella’s date and year of birth is unknown; she was older than her brother, Alexander, who was born in 1198, but may have been born any time in the ten years before. She is not mentioned in the succession crisis of 1195, but that does not mean that she was born after, just that, being the younger daughter, she was not a subject of discussions. Jessica Nelson, in her article for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, suggests that Isabella was born in 1195 or 1196.

The two young princesses became the unwitting pawns in political relations between England and Scotland when the two kings, John and William the Lion, met at Norham, Northumberland, in the last week of July and first week of August 1209. The Scots were in a desperate position, with an ailing and ageing king, and a 10-year-old boy as heir, whilst the English, with their Welsh allies and foreign mercenaries, had an army big enough to force a Scottish submission. The subsequent treaty, agreed at Norham on 7 August, was humiliating for the Scots. John would have the castle at Tweedmouth dismantled, but the Scots would pay an extra £4,000 compensation for the damage they had caused to it. The Scots also agreed to pay 15,000 marks for peace and to surrender hostages, including the king’s two oldest legitimate daughters, Margaret and Isabella.

As a sweetener, John promised to marry the princesses to his sons; although Henry was only 2 years old at the time and Richard was just 8 months, whilst the girls were probably in their early-to-mid teens. The king’s daughters and the other Scottish hostages were handed into the custody of England’s justiciar, at Carlisle on 16 August. How the girls, or their parents, thought about this turn of events, we know not. Given John’s proven record of prevarication and perfidy, King William may have hoped that the promised marriages would occur in good time, but may also have expected that John would find a way out of the promises made.

John’s demand of Margaret and Isabella as hostages, with the sweetener that they would be brides for his own sons, may well have been to prevent Margaret marrying elsewhere. King Philip II of France had expressed interest in a marriage between himself and Margaret, a union John would be keen to thwart. Thus, John’s control of the marriages of Margaret and Isabella would mean that they could not marry against the king of England’s own interests. It also meant that King William had lost two useful diplomatic bargaining chips; marriage alliances could be used to cement political ones, and these had been passed to John, weakening William’s position on the international stage. According to the chronicler Bower, the agreement specified that Margaret would marry John’s son, Henry, while Isabella would be married to an English nobleman of rank.

When the sisters were brought south, they were housed comfortably, as evidence demonstrates. While hostages in England, Margaret and Isabella were kept together, and lived comfortably, although John’s promise of arranging marriages for the girls remained unfulfilled. Payments for their upkeep were recorded by sheriffs and the king’s own wardrobe, which suggests the two princesses spent some time at court. In 1213 Isabella was residing at Corfe Castle in the household of John’s queen, Isabelle d’Angoulême; John’s niece, Eleanor of Brittany, held captive since the failed rebellion of her brother, Arthur of Brittany in 1202, was also there.

One can imagine the frustration of the Scots, to see their princesses languishing in the custody of the English; their inclusion in clause 59 of Magna Carta evidence of this. Unfortunately, King John tore up Magna Carta almost before the wax seals had dried, writing to the pope to have the charter declared void, leaving Alexander to join the baronial rebellion.

When Alexander came to terms with the government of Henry III in December 1217, he pressed for a resolution to the marriages of himself and his sisters, Margaret and Isabella, still languishing in English custody. In June 1220, at a meeting of King Henry III’s minority council, it was agreed that Margaret and Isabella would be married by October 1221 or allowed to return to Scotland.

King John had promised that Alexander would marry one of his daughters and Henry III, or rather his ministers, finally fulfilled this promise in June 1221, when his sister, Joan, was married to the Scots king at York. And it was probably at this event, when the Scottish and English royal families came together in celebration, that Margaret’s own future was finally resolved.

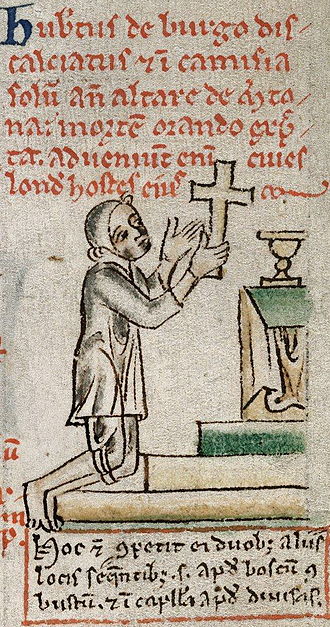

It was decided that she would marry Hubert de Burgh, the king’s justiciar and one of the leading figures of Henry III’s minority government. They were married in London on 3 October 1221, with King Henry himself giving the bride away. It was a major coup for Hubert de Burgh, who came from a gentry family rather than the higher echelons of the nobility; though it was a less prestigious match for Margaret, the daughter of a king. The couple had one child, a girl named Margaret but known as Megotta, who was probably born in the early 1220s.

Isabella, however, remained unmarried and returned to Scotland in November 1222. Isabella’s own marriage prospects may have been damaged by the relatively lowly marriage of her older sister. Nevertheless, Alexander II was keen to look after his sister’s interests and continued to search for a suitable husband. A letter from Henry III alludes to a possible match between Isabella and William (II) Marshal, Earl of Pembroke but the earl was, instead, married to the king’s own younger sister, Eleanor

Isabella’s future was finally settled in June 1225, when she married Roger Bigod, fourth Earl of Norfolk, at Alnwick in Northumberland. On 20 May, the archbishop of York was given respite from his debts in order to attend the wedding of the King of Scots’ sister:

Order to the barons of the Exchequer to place in respite, until 15 days from Michaelmas in the ninth year, the demand for debts they make by summons of the Exchequer from W. archbishop of York, because the archbishop has set out for Alnwick where he is to be present to celebrate the marriage between Roger, son and heir of Earl H. Bigod, and Isabella, sister of the King of Scots.

finerollshenry3.org.uk /content/calendar/roll_022.html#it204_001, 20 May

1225.

Roger was the young son of Hugh Bigod, Earl of Norfolk, who had died earlier in the year, and Matilda Marshal, eldest daughter of William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke. Roger was still a minor, aged about 13, and possibly as much as seventeen years his wife’s junior. In 1224 King Alexander II had levied an aid of 10,000 marks towards the costs of his sisters’ marriages, as well as contributing £1,000 towards Henry III’s 1225 expedition to Gascony, suggesting the Scots king was eager to see both his sisters comfortably settled.

At the time of the marriage, Roger’s wardship was in the hands of Henry III’s uncle, William Longespée, Earl of Salisbury, but it was transferred to King Alexander II in 1226, after Longespée’s death. Now in the custody of the king of Scots, Roger and Isabella moved to Scotland, living at the Scottish court until Roger attained his majority in 1233 and entered into his inheritance.

Ten years after the sealing of Magna Carta, and 16 years after they had been taken hostage, the two Scottish princesses were both finally settled into marriage, though less exalted marriages than their father had wished and hoped for, with English barons, rather than princes or kings. Their younger sister, Marjorie, would also marry into the English nobility in 1235, becoming the wife of Gilbert Marshal, 3rd son of the famed William Marshal who had become Earl of Pembroke the previous year.

Marjorie died in 1244, Isabella in 1253 and Margaret, the eldest, in 1259. Rather unusually for princesses, who would often be married off in foreign lands and separated from family, the 3 sisters would share their final resting place and be buried at the Church of the Black Friars in London.

*

Footnote:

1W.W. Scott, ‘Ermengarde de Beaumont (1233)’, Oxforddnb.com.

Images:

All images courtesy of Wikipedia except Magna Carta, which is ©2015 Sharon Bennett Connolly

Sources:

finerollshenry3.org.uk; W.W. Scott, ‘Ermengarde de Beaumont (1233)’, Oxforddnb.com; Marc Morris, King John; Jessica Nelson, ‘Isabella [Isabella Bigod], countess of Norfolk (b. 1195/1196, 1270)’, Oxforddnb.com; Nelson, Jessica A., ‘Isabella, Countess of Norfolk’, magnacarta800th.com; Louise J. Wilkinson, ‘Margaret, Princess of Scotland’, magnacarta800th.com; W.W. Scott, ‘Margaret, countess of Kent (b. 1187×1195, d. 1259)’, Oxforddnb.com; Keith Stringer, ‘Alexander II (1198–1249)’, Oxforddnb.com; Mackay, A.J.G. (ed.), The Historie and Chronicles of Scotland … by Robert Lindesay of Pitscottie; Ross, David, Scotland: History of a Nation; Church, Stephen, King John: England, Magna Carta and the Making of a Tyrant; Danziger, Danny and John Gillingham, 1215: The Year of Magna Carta; Crouch, David, William Marshal; The Story of Scotland by Nigel Tranter; Matthew Paris, Robert de Reading and others, Flores Historiarum, volume III.

*

My Books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

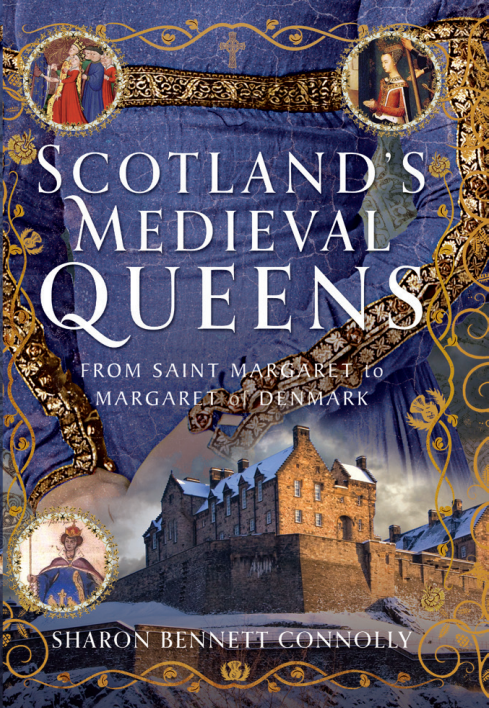

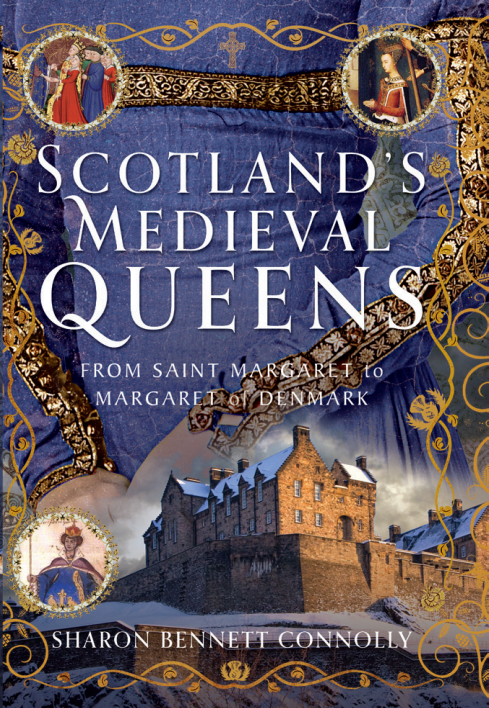

Out now! Scotland’s Medieval Queens

Scotland’s history is dramatic, violent and bloody. Being England’s northern neighbour has never been easy. Scotland’s queens have had to deal with war, murder, imprisonment, political rivalries and open betrayal. They have loved and lost, raised kings and queens, ruled and died for Scotland. From St Margaret, who became one of the patron saints of Scotland, to Elizabeth de Burgh and the dramatic story of the Scottish Wars of Independence, to the love story and tragedy of Joan Beaufort, to Margaret of Denmark and the dawn of the Renaissance, Scotland’s Medieval Queens have seen it all. This is the story of Scotland through their eyes.

Available now from Amazon and Pen and Sword Books

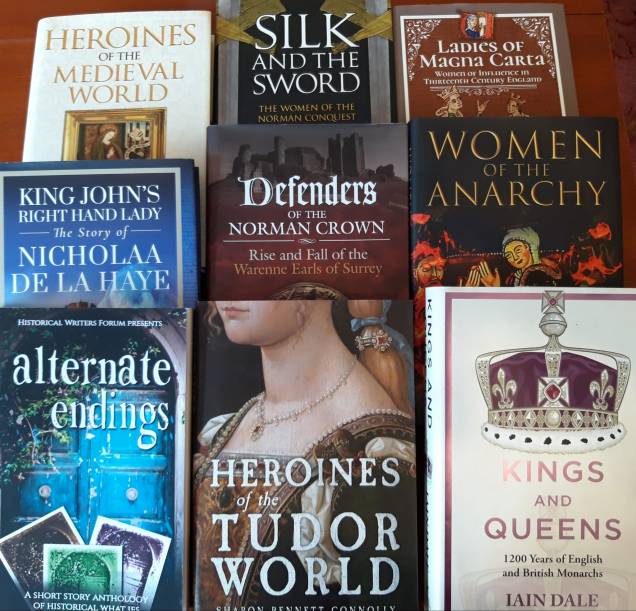

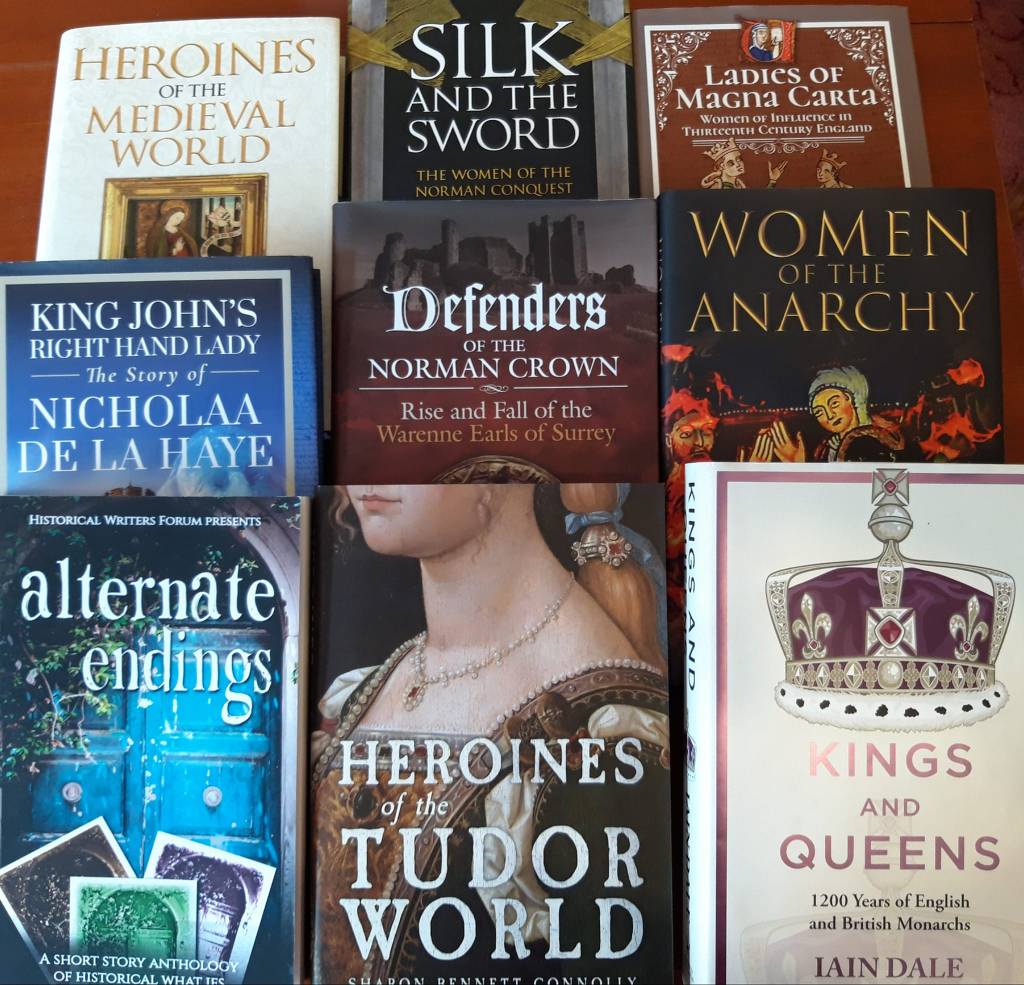

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. Heroines of the Tudor World is now available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how Empress Matilda and Matilda of Boulogne, unable to wield a sword themselves, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It shows how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other. Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

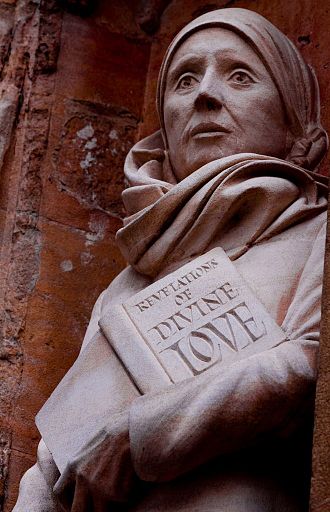

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org. Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell and Elizabeth Chadwick, and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved. Every episode is also now available on YouTube.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

©2020 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS