Born in 1258, probably at Kenilworth Castle, Eleanor de Montfort was the only daughter and sixth child of Eleanor of England. Her mother was the fifth and youngest child of King John and Isabella of Angouleme, and sister of Henry III. Her father was Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, leader of the rebels in the Second Barons’ War.

Eleanor had 5 older brothers; Henry, Simon, Amaury, Guy and Richard.

Her father, Simon de Montfort, is remembered as one of the founders of representative government. He was a leading figure of the Second Barons’ War. He and his eldest son, Henry, were killed at the Battle of Evesham on 4th August 1265. On her father’s death, Eleanor fled to exile in France with her mother and brother, Amuary. The women settled at the Abbey at Montargis until Eleanor of England’s death there in 1275.

In 1265, in return for Welsh support, Simon de Montfort had agreed to the marriage of his daughter, Eleanor, to Llewelyn ap Gruffydd, Prince of Wales. De Montfort’s downfall had postponed the marriage, but in 1275, in a move guaranteed to rile Edward I, King of England, Llewelyn reprised his marriage plans and the couple were married by proxy whilst Eleanor was still in France.

Shortly afterwards, Eleanor set sail for Wales, accompanied by her brother, Amaury, who was now a Papal Chaplain and Canon of York. Believing the marriage would ‘scatter the seeds which had grown from the malice her father had sown’, Edward arranged for Eleanor to be captured at sea. When Eleanor’s ship was taken in the Bristol Channel, the de Montfort arms and banner were found beneath the ship’s boards.

Eleanor was taken to close, but comfortable, captivity at Windsor; whilst her brother Amaury was imprisoned at Corfe Castle for 6 years.

In 1276 Llewelyn having refused to pay homage to Edward I, he was declared a rebel. Faced with Edward’s overwhelming forces, and support slipping away, Llewelyn was forced to submit within a year. The Treaty of Aberconwy reduced his lands to Gwynedd, but paved the way for his marriage to Eleanor, at last; it’s possible that the marriage was one of the conditions of Llewelyn’s submission.

The wedding celebrations of Eleanor de Montfort and Llewelyn ap Gruffydd were an extravagant affair, celebrated at Worcester Cathedral on the Feast of St Edward, 13th October 1278. The illustrious guest list included Edward I and Alexander III, King of Scots. Edward and his brother, Edmund of Lancaster gave Eleanor away at the church door, and Edward paid for the lavish wedding feast.

While the marriage did not prevent further struggles between the Welsh and the English king, there was relative peace for a short time and Eleanor may have encouraged her husband to seek political solutions. She is known to have visited the English court when Princess of Wales; and was at Windsor on such a visit in January 1281. Eleanor herself wrote to Edward on 8 July 1279, not only to assure him of her ‘sincere affection’ and loyalty, but also to warn him against listening to reports unfavourable to Wales from his advisers:

Although as we have heard, the contrary hereto hath been reported of us to your excellency by some; and we believe, notwithstanding, that you in no wise give credit to any who report unfavourably concerning our lord and ourself until you learn from ourselves if such speeches contain truth: because you showed, of your grace, so much honour and so much friendliness to our lord and yourself, when you were at the last time at Worcester.

Anne Crawford, Letters of Medieval Women

As a testament to her diplomatic skills, Eleanor uses words of affection and flattery whilst clearly getting her point across, a technique her predecessor Joan, Lady of Wales, had used to good effect with Henry III. As it had been with Joan, Eleanor, too, was not beyond humbling herself to King Edward in order to achieve her objectives and wrote to him again in October 1280, this time regarding her brother, Amaury, who was still in the king’s custody. She wrote to the king,

with clasped hands, and with bended knees and tearful groanings, we supplicate your highness that, reverencing from your inmost soul the Divine mercy (which holds out the hand of pity to all, especially those who seek Him with their whole heart), you would deign mercifully to take again to your grace and favour our aforesaid brother and your kinsman, who humbly craves, as we understand, your kindness. For if your excellency, as we have often known, mercifully condescends to strangers, with much reason, as we think, ought you to hold out the hand of pity to one so near to you by the ties of nature.

Anne Crawford, Letters of Medieval Women

Amaury was released shortly afterwards.

However, on 22nd March, 1282, Llewelyn’s younger brother, Dafydd, attacked the Clifford stronghold of Hawarden Castle and Llewelyn found himself in rebellion against Edward I yet again. At the same time, Eleanor was in the final few months of her pregnancy and Llewelyn held off taking the field until the birth of his much hoped for heir.

Eleanor and Llewelyn’s only child, a daughter, Gwenllian, was born on 19th June 1282; Eleanor died the same day.

Llewelyn himself was killed in an ambush on 11 December of the same year, at Builth, earning himself the name of Llewelyn the Last – the last native Prince of Wales.

Their daughter, Gwenllian was given into the guardianship of her uncle, Dafydd ap Gruffydd, but was taken into Edward I’s custody when David was defeated and captured by the English. She was sent to be raised at the Gilbertine convent at Sempringham, where she eventually became a nun. She died there on 7th June 1337, the last of her father’s line. It is said that she was never allowed to speak, hear or learn her native language. It has been assumed that she was not aware of her heritage, although she was once visited by her cousin, Edward III, who paid £20 annually for her food and clothing. However, as David Pilling has pointed out, she does in fact call herself ‘Princess of Wales, daughter of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd’ in a petition inside the volume of petitions from Wales edited by William Rees.

Eleanor de Montfort was the first woman known to have used the title Princess of Wales. She was buried alongside her aunt Joan, illegitimate daughter of King John and wife of Llewelyn the Great, at Llanfaes on the Isle of Anglesey.

*

Sources: castlewales.com; snowdoniaheritage.info; Marc Morris A Great and Terrible King; David Williamson Brewer’s British royalty; Mike Ashley The Mammoth Book of British kings & Queens; Alison Weir Britain’s Royal Families; Roy Strong The Story of Britain; Dan Jones The Plantagenets; the Kings who Made England; Chronicles of the Age of Chivalry Edited by Elizabeth Hallam; The Oxford Companion to British History; The History Today Companion to British History; Derek Wilson The Plantagenets; Anne Crawford, Letters of Medieval Women; author David Pilling.

Pictures taken from Wikipedia, except that of Edward I, Alexander III and Llewelyn, which was taken from castlewales.com.

*

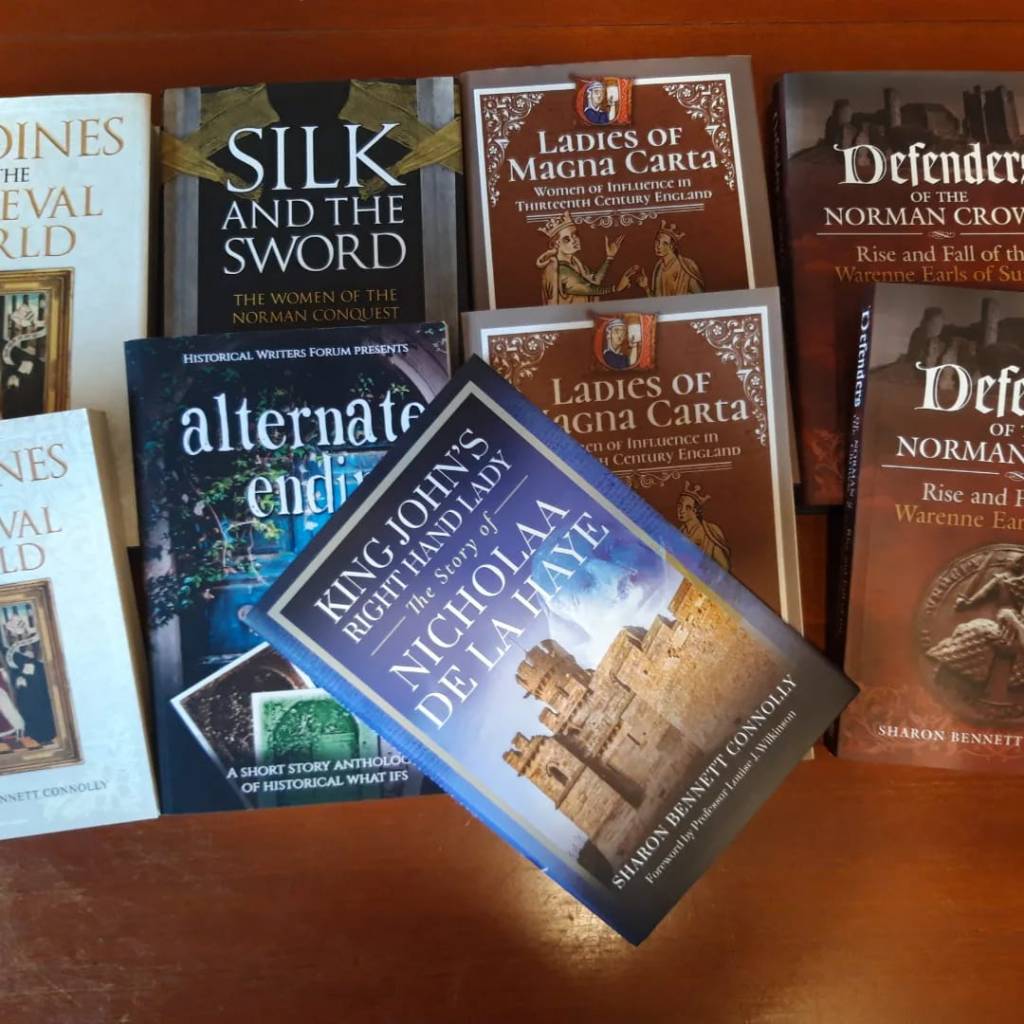

My Books:

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available, please get in touch by completing the contact me form.

Out now: King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye

In a time when men fought and women stayed home, Nicholaa de la Haye held Lincoln Castle against all-comers, gaining prominence in the First Baron’s War, the civil war that followed the sealing of Magna Carta in 1215. A truly remarkable lady, Nicholaa was the first woman to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Her strength and tenacity saved England at one of the lowest points in its history. Nicholaa de la Haye is one woman in English history whose story needs to be told…

King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is now available from Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

Coming 15 January 2024: Women of the Anarchy

On the one side is Empress Matilda, or Maud. The sole surviving legitimate child of Henry I, she is fighting for her birthright and that of her children. On the other side is her cousin, Queen Matilda, supporting her husband, King Stephen, and fighting to see her own son inherit the English crown. Both women are granddaughters of St Margaret, Queen of Scotland and descendants of Alfred the Great of Wessex. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how these women, unable to wield a sword, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It show how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other.

Available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK.

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, of the successes and failures of one of the most powerful families in England, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Defenders of the Norman Crown: Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey is now available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org.

Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org.

Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org.

Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

*

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

©2023 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS

*

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

*

©2015 Sharon Bennett Connolly

Reblogged this on karenstoneblog and commented:

Another fascinating nibble on history

LikeLike

Thank you Karrie.

LikeLike

Thank you for sharing such information. I enjoyed it thoroughly.

LikeLike

Thank you very much.

LikeLike

You really do a great job! Keep it up. 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you for the encouragement, Lenora, it means a lot to me. I’m thoroughly enjoying the writing, so I will certainly try to keep it up – it’s great fun. 🙂

LikeLike

Really interesting article!

LikeLike

Thank you Christoph, much appreciated.

LikeLike

Just came across this site – very interesting, informative and well writt.

LikeLike

Thank you Sue, that’s lovely to hear. Welcome – I’m so happy you found us. 🙂

LikeLike

Excellent as always. I always look forward to your postings 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you Jean,, that’s lovely to hear. 🙂

LikeLike

very interesting

LikeLike

Thank you Ali 🙂

LikeLike

Great article. But didn’t Guy deb Montfort have daughters as well? I’m sure I read that there are descendants today from those daughters.

LikeLike

Hi Thomas, thanks for the comment. Yes, I believe Guy de Montfort had a couple of daughters after he married in Italy. Elizabeth Woodville, wife of Edward IV, was descended from him, which makes the current royal family his descendants. Best wishes, Sharon

LikeLike