Ooh, I have just time to sneak in one more post for 2022!

First, though, I would like to take the opportunity to thank all my readers, near and far, for sticking with me and helping me to make History…the Interesting Bits a blog that people want to read.

I would like to wish each and every one of you a Happy and Healthy New Year. May 2023 be kind and generous to you all!

So, on with the article…

Following on from my 10 Facts About Women and Magna Carta, I thought I would revisit the Norman Conquest and started thinking about I found most interesting when writing about 1066 and the years either side. And here’s what I discovered:

1. Not all primary sources are contemporary.

Let me explain. Of course, all sources written in the 11th century are primary sources, but you do find people quoting sources as primary sources – only to discover that they were written 100 or even 200 years after the events.

One such legend, appearing two centuries after the events, suggested that Emma of Normandy’s relationship with her good friend, Bishop Stigand, was far more than that of her advisor and that he was, in fact, her lover – although the legend did get its bishops mixed up and named Ælfwine, rather than Stigand, as Emma’s lover. The story continues that Emma chose to prove her innocence in a trial by ordeal, and that she walked barefoot over white-hot ploughshares. Even though the tale varies depending on the source, the result is the same; when she completed the ordeal unharmed, and thus proven guiltless, she was reconciled with her contrite son, Edward.

However, there is no 11th century source for this event and it seems to have been created to explain Emma’s estrangement from her son, Edward the Confessor.

2. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is the most famous source of 11th century news.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle gives wonderful snippets of information about life in Anglo-Saxon England – and the weather! If you have ever wondered where the English get their obsession with the weather, read the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. It is also very dramatic.

For example, the year 1005 starts with; ‘Here in this year there was the great famine throughout the English race, such as no-one ever remembered on so grim before…’

1032 relates; ‘Here in this year appeared that wild-fire such as no man remembered before, and also it did damage everywhere in many places.’

And 1039 opens with ‘Here came the great gale…’

In 1053 we read, ‘Here [1052] was the great wind on the eve of the Feast of St Thomas, and the great wind was also all midwinter…’

And, of course, in 1066 we read about the appearance of Halley’s Comet; ‘Then throughout all England, a sign such as man ever saw before was seen in the heavens. Some me declared that it was the star comet, which some men called the ‘haired’ star; and it appeared first on the eve of the Great Litany, 24 April, and shone thus all the week….’

3. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a fabulous source of news about church leaders.

Don’t get me wrong, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is invaluable to anyone studying the history of Anglo-Saxon Britain, but you can tell it was written by monks. There are some years where you learn little more than which church leader died, and who replaced him.

For example, the entry for 1023 from the E chronicle; ‘Here Bishop Wulfstan passed away, and Ælfric succeeded…’

And in 1032; ‘In the same year Ælfsige, bishop in Winchester, passed away, and Ælfwine, the king’s priest, succeeded to it.’

The only entry in the E Chronicle in 1033 was; ‘Here in this year Merehwit, bishop in Somerset, passed away, and he is buried in Glastonbury.’

And again in 1034; ‘Here Bishop Æthelric passed away.’

4. Not all inheritance was based on primogeniture.

Primogeniture, where the eldest son inherited from his father, was not unusual in 11th century England; when Earl Godwin of Wessex died, his eldest surviving son, Harold, succeeded him. However, it was not yet established as the definitive rule of inheritance of later centuries. When Siward, Earl of Northumbria, died in 1055 his heir, Waltheof, was still a child and too young to hold such a formidable position on the borders of Scotland. The earldom was given to Tostig Godwinson, the favourite brother of Edward the Confessor’s queen, Edith. Though he didn’t do a great job with it…

And in the opening days of 1066, when Edward the Confessor died, the ætheling, Edgar was only a teenager, and so was passed over as king for the more mature and militarily experienced Harold Godwinson, Earl of Wessex, who became King Harold II.

5. Travel to distant places was not uncommon for the nobility.

At different times in the 11th century, both King Cnut and Tostig Godwinson are known to have travelled to Rome; indeed, during his trip to Rome in 1027, Cnut was present at the coronation of Holy Roman Emperor, Conrad II and arranged for the marriage of his daughter by Emma of Normandy, Gunhilda, to Conrad’s son, the future King Henry III of Germany.

As for Tostig, travelling to Rome was not without its dangers, and shortly after leaving the city, his travelling party was caught up in a local dispute between the papacy and the Tuscan nobility; they were attacked. Tostig was able to escape by the ruse of one of his own thegns, a man named Gospatric, who pretended to be the earl.

Tostig and Harold’s brother, Swegn Godwinson, who had murdered his own cousin, even went on pilgrimage to Jerusalem – barefoot – he died on the journey home.

And when I started writing Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest I discovered that there are several links to the story of 1066 with the Russian principality of Kyiv. The baby sons of England’s short-lived king, Edmund II Ironside, who reigned and died in 1016, were given sanctuary and protection in Kyiv, saving them from the clutches of Edmund’s successor, King Cnut. The first wife of Harald Hardrada, the third contender for the English throne in 1066, Elisiv, was a Kyivan princess. And after the Conquest, Harold II Godwinson’s own daughter by Edith Swanneck, Gytha, would make her life in Kyiv as the wife of Vladimir II Monomakh and as the mother of Mstislav the Great, the last ruler of a united Kievan Rus. Vladimir was the nephew of Harald Hardrada’s first wife, the Kyivan princess, Elisiv.

6. Having 2 wives at the same time was not THAT unusual.

In the story of 1066 there were not one BUT three men who had two wives simultaneously.

Harold Godwinson is known for having been in a relationship with the famous Edith Swanneck for 20 years before becoming King, and then marrying Ealdgyth of Mercia without divorcing Edith. Edith is often referred to as Harold’s concubine, but most historians agree that she was his ‘hand-fast’ wife and had undergone a Danish – rather than Christian – style of wedding with Harold. Edith was no ignorant peasant, she was a wealthy woman in her own right and it is highly doubtful she would have accepted being Harold’s mistress, and raising his children, without some kind of marital protection.

Harald Hardrada also married a second ‘wife’, whilst still being married to Elisiv. Elisiv had given the Norwegian king two daughters, but his second wife, Thora, gave him two sons, Magnus and Olaf, who each succeeded their father as King of Norway.

King Cnut was the first to take two wives; he had two sons by Ælfgifu of Northampton before marrying Emma of Normandy and producing a second family. The chronicles, however, claim that Ælfgifu’s sons were not the children of Cnut, with John (also known as Florence) of Worcester saying, ‘Ælfgiva desired to have a son by the king, but as she could not, she caused the new-born child of a certain priest to be brought to her, and made the king fully believe that she had just borne him a son’. And the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle claimed ‘[King] Harold [I Harefoot] also said that he was the son of king Canute and Ælfgiva of Northampton, although that is far from certain; for some say that he was the son of a cobbler, and that Ælfgiva had acted with regard to him as she had done in the case of Swein: for our part, as there are doubts on the subject, we cannot settle with any certainty the parentage of either.’

7. There were some incredible, strong women in the 11th century.

The story of the Norman Conquest invariably revolves around the men involved, Edward the Confessor, Harold II, William the Conqueror, Harald Hardrada, and so on. However, there were some amazing women whose strength and perseverance helped to steer and shape the events of the era.

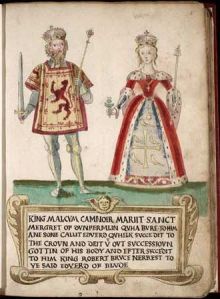

There were, of course, the queens, Emma of Normandy, Edith of Wessex and Matilda of Flanders, who supported their husbands and helped to shape and – even – preserve history, with Emma and Edith both commissioning books to tell the stories of their times and Matilda being the image of queenship that all future queens of England modelled themselves on.

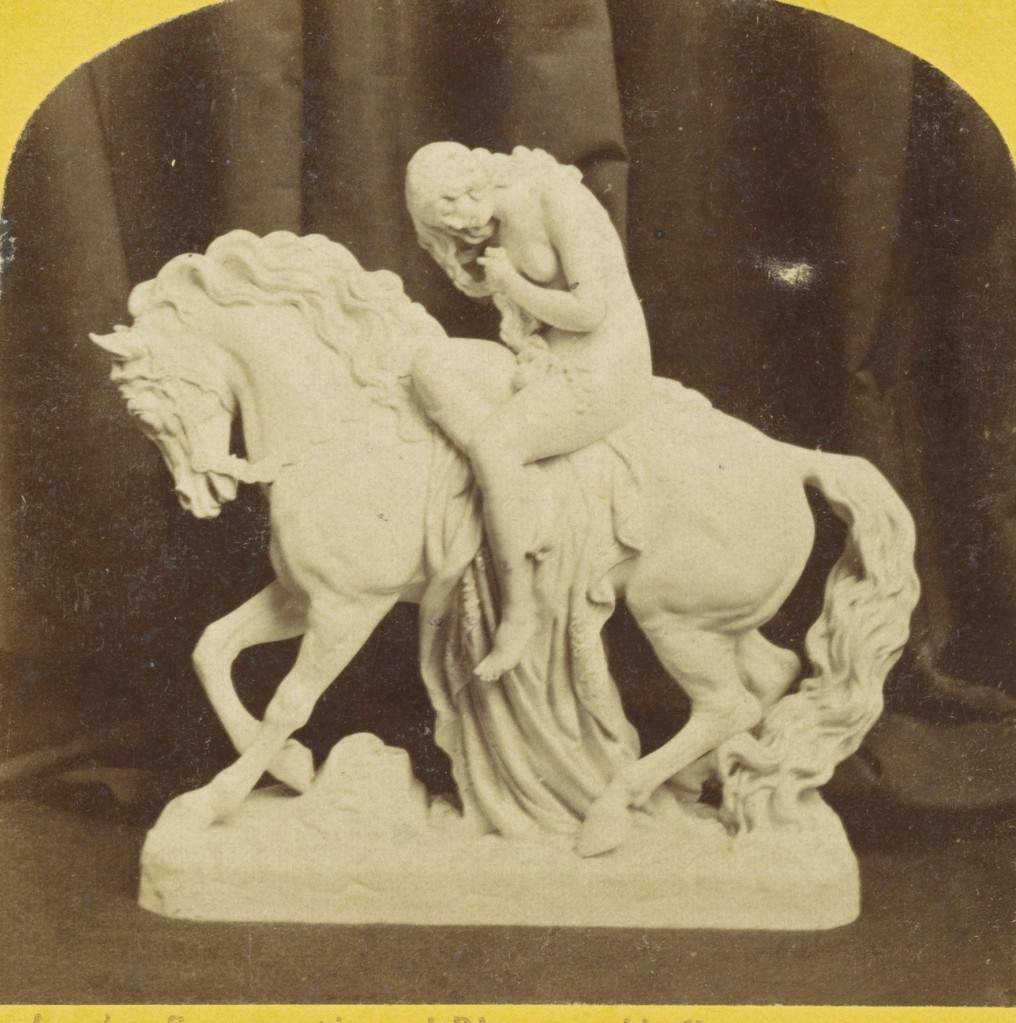

There was also the notorious Lady Godiva, who was probably a lot less scandalous than the legend, of her riding naked through Coventry, leads us to believe. And the incredible Gytha of Wessex, a woman whose story is entwined with every aspect of the period. From the reign of Cnut to that of William the Conqueror, Gytha and her family were involved in so many aspects of the 11th century, from the rise of her sons, through the Battle of Hastings itself, to the English resistance in the years immediately following the Conquest. Gytha was not one to give up easily, despite the horrendous losses her family suffered (three of her sons died in one single day at Hastings), she encouraged her grandsons to lead the opposition against the Conqueror in the west, but her eventual failure saw her seek shelter in Flanders, where she disappears from the pages of history.

8. There is still so much we don’t know!

What you discover when researching the 11th century and the Norman Conquest is that there are gaps in our knowledge. For instance, we do not know why Harold was travelling to Europe in 1064, when he was shipwrecked and became a guest at the court of William, Duke of Normandy (the future William the Conqueror). The Bayeux Tapestry depicts Harold swearing an oath during his stay there. Was Harold promising to support William’s claim to England when Edward the Confessor died?

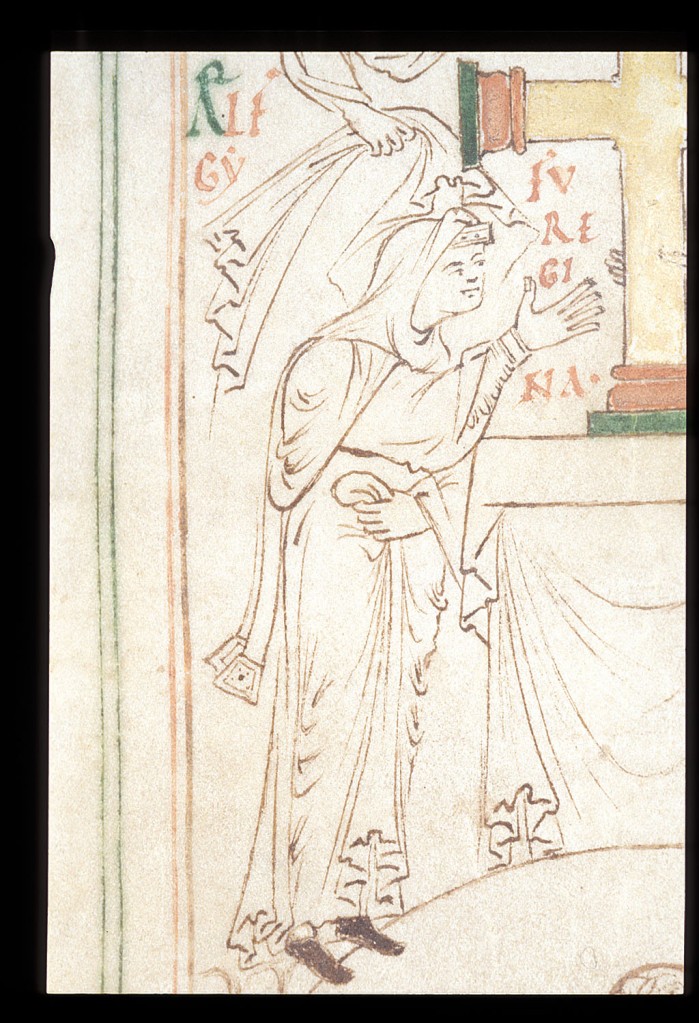

The Bayeux Tapestry has another tantalising mystery. That of Ӕlfgyva. Ӕlfgyva is depicted in a doorway with a priest touching her cheek. Whether the touch is in admonishment or blessing is open to interpretation. Above her head, written in Latin, is the incomplete phrase ‘Here a certain cleric and Ӕlfgyva’. But who was the mysterious Ӕlfgyva? Will we ever know?

Historical Writers Forum hosted a fabulous debate on ‘Ӕlfgyva’: The Mysterious Woman in the Bayeux Tapestry, which is available on YouTube. Hosted by Samantha Wilcoxson, it features myself, Pat Bracewell, Carol McGrath and Paula Lofting.

*

I would like to take this opportunity to thank you all for your support and encouragement over the years, and to wish you all a Happy and Healthy New Year.

May 2023 be generous to you.

All my love, Sharon xx

*

A version of this article was first published on Carol McGrath’s website in December 2018

Images:

Courtesy of Wikipedia, except King Harold II, which is ©2022 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS.

Sources:

A Historical Document Pierre Bouet and François Neveux, bayeuxmuseum.com/en/un_document_historique_en; The Mystery Lady of the Bayeux Tapestry (article) by Paula Lofting, annabelfrage.qordpress.com; Ӕlfgyva: The Mysterious lady of the Bayeux Tapestry (article) by M.W. Campbell, Annales de Normandie; The Bayeux Tapestry, the Life Story of a Masterpiece by Carola Hicks; Æthelred II [Ethelred; known as Ethelred the Unready] (c. 966×8-1016) (article) by Simon Keynes, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, oxforddnb.com; Britain’s Royal Families; the Complete Genealogy by Alison Weir; Queen Emma and the Vikings: The Woman Who Shaped the Events of 1066 by Harriet O’Brien; The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle translated by James Ingram; On the Spindle Side: the Kinswomen of Earl Godwin of Wessex by Ann Williams; Swein [Sweyn], earl by Ann Williams, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, oxforddnb.com, 23 September 2004; Ӕlfgifu [Ӕlfgifu of Northampton (fl. 1006-1036) (article) by Pauline Stafford, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, oxforddnb.com; The Chronicle of John of Worcester, translated and edited by Thomas Forester, A.M; The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles edited and translated by Michael Swanton.

*

My Books:

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available, please get in touch by completing the contact me form.

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, of the successes and failures of one of the most powerful families in England, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Defenders of the Norman Crown: Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey is now available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, Bookshop.org and Book Depository.

1 family. 8 earls. 300 years of English history!

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, Bookshop.org and from Book Depository worldwide.

Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, Bookshop.org and Book Depository.

Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, Bookshop.org and Book Depository.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

*

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

*

©2022 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS.