For many years, although William Longespée’s father was known, the identity of his mother was very much in question. William Longespée was the son of Henry II, king of England, and it was thought that his mother was a common harlot, called Ikenai. In that case, he would have been a full brother of another of Henry’s illegitimate sons, Geoffrey, Archbishop of York. There were also theories that his mother was Rosamund Clifford, famed in ballads as ‘the Fair Rosamund’. However, it is now considered beyond doubt that his mother was, in fact, Ida de Tosney, wife of Roger Bigod, Earl of Norfolk, from a relationship she had with the king before her marriage.

There are two extant pieces of evidence supporting this. The first is a charter in the cartulary of Bradenstoke Priory, made by William Longespée, in which he refers explicitly to his mother as ‘Countess Ida, my mother’. There is also a prisoner roll from after the Battle of Bouvines, in which a fellow captive, one the sons of Ida and the earl of Norfolk, Ralph Bigod, is listed as ‘Ralph Bigod, brother [halfbrother] of the earl of Salisbury’. Ralph was a younger son of Earl Roger and Ida and had been fighting under Longespée’s command in the battle in which both were taken prisoner.

Ida was probably the daughter of Roger (III) de Tosney, a powerful Anglo-Norman lord, and his wife, also called Ida. She was made a royal ward after her father’s death and became mistress of King Henry II sometime afterwards. She gave the king one son, William Longespée, who was born around 1176, making him ten years younger than the king’s youngest legitimate son, John. Around Christmas 1181, Ida was married to Roger Bigod, Earl of Norfolk and through his mother’s Norfolk family, Longespée had four half-brothers, Hugh, William, Ralph and Roger and two half-sisters, Mary and Margery.

Despite the misunderstandings over his mother, the identity of William Longespée’s father was never in doubt. He was Henry II’s son and acknowledged by his father; as an illegitimate son of Henry II, William Longespée’s fortune and position in society were inextricably linked with the fortunes of his royal half-brothers, King Richard I and King John, both of whom he served. Longespée adopted the coat of arms of his paternal grandfather, Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou, of azure, six leoncels rampant or [gold], to emphasise his descent from the Angevin counts.

The moniker of Longespée (also Lungespée or Longsword) harkens back to his Norman forebear and namesake William Longsword, second Duke of Normandy (reigned 928–942), from whom he was descended through his father, the king. Little is known of Longespée’s childhood, upbringing or education, though a letter of 1220 that Longespée sent to Hubert de Burgh reminds the justiciar that they were raised together, probably fostered in a noble household. In 1188, Longespée had been given the manor of Appleby in Lincolnshire by his father, but he did not come into prominence until the reign of his half-brother Richard I.

It was King Richard who arranged Longespée’s marriage to the rich heiress Ela of Salisbury. Ela’s father, William, Earl of Salisbury, had carried the sceptre at Richard I’s coronation, in 1194 he had served as high sheriff of Somerset and Dorset and in 1195 campaigned with King Richard in Normandy. In the same year, he was one of the four earls who supported the canopy of state at Richard’s second coronation, and attended the great council, called by the king, at Nottingham. He died in 1196, leaving his only child, Ela, as his sole heir. Ela became Countess of Salisbury in her own right, and the most prized heiress in England.

On her father’s death, Ela’s wardship passed into the hands of the king himself, Richard I, the Lionheart. The king saw Ela as the opportunity to reward his loyal, but illegitimate, half-brother, William Longespée, by offering him her hand in marriage; the Salisbury lands being seen as a suitable reward for a king’s son, especially one born out of wedlock. They would give Longespée a power base in England. Ela and Longespée were married in the same year her father died, 1196. At the time of his marriage to Ela, Longespée was in his early-to-20s, while his bride was not yet 10 years old, although she would not have been expected to consummate the marriage until she was 14 or 15, and they would not have lived as husband and wife until Ela was at least 12 years old, the church’s legal age of marriage for a girl.

Ela’s new husband was an experienced soldier and statesman and would be able to protect Ela, her lands and interests. William acquired the title Earl of Salisbury by right of his wife and took over the management of the vast Salisbury estates.

William (I) Longespée had an impressive military and political career during the reigns of his half-brothers. He first served in Normandy with Richard between 1196 and 1198, attesting several charters for his brother at Château Gaillard, and taking part in the campaigns against King Philip II of France, gaining essential military experience. He took part in John’s coronation on 27 May 1199 and was frequently with John thereafter. The half-brothers appear to have enjoyed a very cordial relationship; the court rolls record them gaming together and John granting Longespée numerous royal favours, from gifts of wine to an annual pension. By 1201 Longespée, along with William Marshal and Geoffrey fitz Peter, Earl of Essex ‘were seen by John at this stage in his reign as the main props to his rule, and lavish gifts followed.’1

Although Longespée’s marriage to Ela of Salisbury gave him rank and prestige, it was not a wealthy earldom. The barony commanded fifty-six knights’ fees and gave the earl custody of the royal fortress of Salisbury, but Longespée had no castle of his own. He was made sheriff of Wiltshire on 3 separate occasions, 1199–1202, 1203–1207 and 1213–1226, but was never granted the position as a hereditary right by the king. As sheriff, it was Longespée’s task to hunt down the famous outlaw Fulk Fitzwarin, whom he besieged in Stanley Abbey in 1202. When Fitzwarin and his band of about 30 men were pardoned in 1203, Longespée was among those who secured the pardon from the king. During his career, William was also entrusted with several important diplomatic missions. In 1202 he negotiated a treaty with Sancho VII of Navarre and in 1204 he and William Marshal escorted the Welsh prince Llywelyn to the king at Worcester. He was also sent to Scotland on a diplomatic mission to King William the Lion in 1205 and was with John at York in November 1206 when the two kings met. The earl was also involved in the election of his nephew, Otto, as German emperor, heading an embassy to the princes of Germany which resulted in Otto’s coronation.

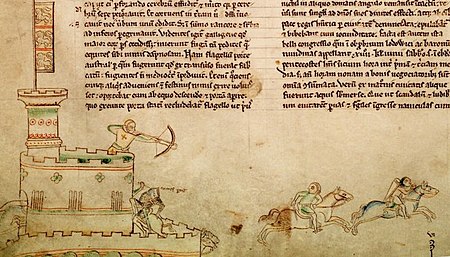

William Longespée’s most prominent role during the reign of King John, however, was as a military leader. He was a commander of considerable ability. In August 1202 he had fought alongside William Marshal and William de Warenne, Earl of Surrey, hounding the retreating forces of King Philip of France. The French king had withdrawn from the siege of Arques following news of John’s victory over his nephew, Arthur, at Mirebeau. Longespée and his lightly-armed fellow earls, however, narrowly escaped capture from a counterattack led by William de Barres. Following the fall of Normandy, Longespée was given command of Gascony in May 1204. In September of the same year he was also given custody of Dover castle and made warden of the Cinque Ports; he retained both offices until May 1206. In 1208 Longespée was appointed warden of the Welsh Marches and in 1210 he joined King John on the Irish expedition which had been prompted by William de Braose fleeing to Ireland to escape John’s persecution. In 1213 he allied with the counts of Holland and Boulogne, led an expeditionary force to the aid of Count Ferrand of Flanders against King Philip II and on 30 May he achieved a significant naval victory when his forces destroyed the French fleet off the Flemish coast near Damme, burning many enemy ships and capturing others. The victory forced King Philip to abandon plans for an invasion of England.

In 1214 William Longespée commanded an army in northern France for the king, while John was campaigning in Poitou. He managed to recover most of the lands lost by the count of Flanders and,, in July of the same year, he commanded the right-wing of the allied army at the Battle of Bouvines, alongside Renaud de Dammartin, Count of Boulogne. William fought bravely but was captured, after being clubbed on the head by Philippe, the bishop of Beauvais. According to the Histoire de Guillaume le Maréchal the battle had been fought against the earl’s advice, and if it were not for Longespée’s own heroic actions, Emperor Otto would have been taken prisoner or, worse, killed. The battle was a military disaster for the English forces in France and ended John’s hopes of recovering his Continental possessions. William Longespée was held prisoner for almost a year. He was eventually ransomed and exchanged in March 1215, for John’s prisoner, Robert, son of the count of Dreux, who had been captured at Nantes in 1214.

William Longespée was back in England by May 1215 and appointed to examine the state of royal castles. However, England was reaching crisis point by this time, with the rebellion of the barons gathering pace. Although unable to prevent rebels from gaining control of London, he was effective against the rebels in Devon, forcing them to abandon Exeter. He was named among those barons who had advised John to grant Magna Carta, though whether he was actually present at Runnymede, when the charter was sealed, is unknown. He was granted lands from the royal demesne in August 1215 in compensation for the loss of Trowbridge, which had been returned to Henry de Bohun, one of the twenty-five barons appointed to the committee to oversee the enforcement of the terms of Magna Carta. Also in 1215, following the fall of Rochester, Longespée was given the task of containing the rebels in London, while John led the rest of his forces north. Alongside Faulkes de Bréauté and Savaric de Mauléon, he led a punitive chevauchée through Essex, Hertfordshire, Middlesex, Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire. However, in the early weeks of 1216, when Walter Buc’s Brabançon mercenaries ravaged the Isle of Ely, it was Longespée who protected the women from their worst excesses.

Longespée was still supporting John when Louis, the Dauphin, landed on 21 May 1216; however, Louis’ rapid advance through the southern counties, and the fall of Winchester in June 1216, led the earl of Salisbury to submit and ally with Louis. He remained in opposition to his half-brother for the rest of John’s life. Unfounded rumours, recorded by William the Breton, suggested that Longespée’s desertion of John was caused by the king’s seduction of Ela while the earl was a prisoner of war in France. It seems more likely that, like so many others, he saw John’s cause as lost and decided to cut his own losses. With Longespée’s defection, and that of William de Warenne, Earl of Surrey, John’s support was severely diminished and in retaliation, John ordered his brother’s lands seized in August 1216.

Despite the death of King John in October 1216, Longespée remained with Louis and even called for Hubert de Burgh to surrender Dover to the French. However, when Louis returned to France in March 1217, to gather reinforcements, Longespée submitted to the king, swearing loyalty to his 9-year-old nephew, Henry III. He was also absolved of the sentence of excommunication which had been passed on all those who had defected to Louis. Along with Longespée, William Marshal’s eldest son, William (II), and a hundred other men from Wiltshire and the south-west, returned to the king’s peace. Longespée was now instrumental in driving the French from England and defeating the remaining rebel barons. He was part of William Marshal’s army at the Battle of Lincoln Fair on 20 May 1217, when Lincoln Castle and its formidable castellan, Nicholaa de la Haye, were finally relieved following a three-month siege by the French under the Comte de Perche.

We know nothing of William and Ela’s married life, although it appears to have been a happy one. The couple had at least eight children together, if not more; 4 boys and 4 girls. Of their 3 youngest boys, Richard became a canon at the newly built Salisbury Cathedral, Stephen became seneschal of Gascony and justiciar of Ireland, and their youngest son, Nicholas, was elected bishop of Salisbury in 1291; he was consecrated at Canterbury by Archbishop John Pecham on 16 March 1292. Already in his sixties, Nicholas died on 18 May 1297. In 1216, the oldest son, William II Longespée, fourth Earl of Salisbury, was granted marriage by King John to Idonea, granddaughter and sole heiress of the formidable Nicholaa de la Haye. Both children were very young when the grant was made, with Idonea being, possibly, no older than 8, the youngest age that a betrothal was sanctioned by the church, though she could not be married until the age of 12. John ordered that:

The sheriffs of Oxford and of Berkshire are commanded that they cause William, Earl of Salisbury, to have the right of marriage of the daughter of Richard de Canville, born of Eustacia, who was the daughter of Gilbert Basset and wife of the said Richard, for William his first-born son by his wife Ela, Countess of Salisbury, with all the inheritance belonging to the said Richard’s daughter from her mother in their Bailiwicks. Witness myself, at Reigate, the twenty second day of April.

Letter from King John, 22 April 1216

This order may be the source of Nicholaa de la Haye’s later wranglings with Salisbury, given that it appears to pass all of Idonea’s inheritance into the custody of Longespée, regardless of the fact Nicholaa was still very much alive at this time. It also suggests that Richard de Canville, Idonea’s father, may have already been deceased, despite most mentions of him have him dying in the first quarter of 1217. Young William and Nicholaa de la Haye would spend several years in legal disputes over the inheritance of Nicholaa’s Lincolnshire holdings. William (II) Longespée went on crusade with Richard, Earl of Cornwall, in 1240–1 and later led the English contingent in the Seventh Crusade led by Louis IX of France. His company formed part of the doomed vanguard, which was overwhelmed at Mansourah in Egypt on 8 February 1250. William’s body was buried in Acre, but his effigy lies atop an empty tomb in Salisbury Cathedral. His mother, Ela, is said to have experienced a vision of her son’s last moments at the time of his death.

Of the William and Ela’s 4 daughters, Petronilla died unmarried, possibly having become a nun. Isabella married William de Vescy, Lord of Alnwick, and had children before her death in 1244. Another daughter, named Ela after her mother, married firstly Thomas de Beaumont, Earl of Warwick and, secondly, Phillip Basset; sadly, she had no children by either husband. A 4th daughter, Ida, married Walter fitzRobert; her second marriage was to William de Beauchamp, Baron Bedford, by whom she had 6 children.

As a couple, William Longespée and Ela were great patrons of the church, laying the 4th and 5th foundation stones for the new Salisbury Cathedral in 1220. William de Warenne, Earl of Surrey and a cousin to Ela – Ela’s father was half-brother to William’s mother, Countess Isabel de Warenne – also laid a foundation stone. In the first half of the 1220s, Longespée played an influential role in the minority government of Henry III and also served in Gascony to secure the last remaining Continental possessions of the English king. In 1225 he was shipwrecked off the coast of Brittany and a rumour spread that he was dead. While he spent months recovering at the island monastery of Ré in France, Hubert de Burgh, first Earl of Kent and widower of Isabella of Gloucester, proposed a marriage between Ela and his nephew, Reimund. Ela, however, would not even consider it, insisting that she knew William was alive and that, even if he were dead, she would never presume to marry below her status. It has been suggested that she used clause 8 of Magna Carta to support her rejection of the offer:

‘No widow is to be distrained to marry while she wishes to live without a husband.’

Clause 8, 1215 Magna Carta

However, as it turned out, William Longespée was, indeed, still alive and he eventually returned to England and his wife; after landing in Cornwall, he made his way to Salisbury. From Salisbury he went to Marlborough to complain to the king that Reimund had tried to marry Ela whilst he was still alive. According to the Annals and antiquities of Lacock Abbey Reimund was present at Longespée’s audience with the king, confessed his wrongdoing and offered to make reparations, thus restoring peace.

Unfortunately, Longespée never seems to have recovered fully from his injuries and died at the royal castle of Salisbury shortly after his return home, on 7 March 1226, amid rumours of being poisoned by Hubert de Burgh or his nephew. He was buried in a splendid tomb in Salisbury Cathedral.

Although the title earl of Salisbury still belonged to his wife, his son, William (II) Longespée was sometimes called Earl of Salisbury, but never legally bore the title as he died before his mother. Ela did not marry again. On her husband’s death, she was forced to relinquish her custody of the royal castle at Salisbury, although she did eventually buy it back. Importantly, she was allowed to take over her husband’s role as sheriff of Wiltshire, which he had held 3 times in his career and continuously from 1213 until his death in 1226. Ela herself served twice as sheriff of Wiltshire from 1227 until 1228 and again from 1231 to 1237.

Ela of Salisbury outlived both her eldest son and grandson. She was succeeded as Countess of Salisbury by her great-granddaughter, Margaret, who was the daughter of William III Longespée. Just over 10 years after she was widowed, Ela entered her own foundation of Lacock Priory in 1237 and became the first Abbess when it was upgraded to an Abbey in 1239. As Abbess, Ela was able to secure many rights and privileges for the abbey and its village. She obtained a copy of the 1225 issue of Magna Carta, which had been given to her husband for him to distribute around Wiltshire. She remained Abbess for 20 years, resigning in 1259. Ela remained at the abbey, however, and died there on 24th August, 1261.

*

Footnotes:

1David Crouch, William Marshal

Images courtesy of Wikipedia.

Sources:

finerollshenry3.org.uk; Oxforddnb.com; magnacarta800th.com; Church, Stephen, King John: England, Magna Carta and the Making of a Tyrant; Danziger, Danny and John Gillingham, 1215: The Year of Magna Carta; Crouch, David, William Marshal; Matthew Paris, Robert de Reading and others, Flores Historiarum, volume III; Robert Bartlett England Under the Norman and Angevin Kings 1075-1225; Dan Jones The Plantagenets; the Kings who Made England; Maurice Ashley The Life and Times of King John; Roy Strong The Story of Britain; Oxford Companion to British History; Mike Ashley British Kings & Queens; David Williamson Brewer’s British Royalty; Rich Price King John’s Letters Facebook page; Elizabeth Hallam, editor, The Plantagenet Chronicles; Donald Matthew, King Stephen; Medieval Lands Project on the Earls of Surrey, Conisbrough Castle; Farrer, William and Charles Travis Clay, editors, Early Yorkshire Charters, Volume 8: The Honour of Warenne; Rev. John Watson, Memoirs of the Ancient Earls of Warren and Surrey and their Descendants to the Present Time; Morris, Marc King John: Treachery, Tyranny and the Road to Magna Carta; doncasterhistory.co.uk.

*

My books

My Books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available, please get in touch by completing the contact me form.

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, of the successes and failures of one of the most powerful families in England, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Defenders of the Norman Crown: Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey is now available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, Bookshop.org and Book Depository.

1 family. 8 earls. 300 years of English history!

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, Bookshop.org and from Book Depository worldwide.

Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, Bookshop.org and Book Depository.

Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, Bookshop.org and Book Depository.

*

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

©2021 Sharon Bennett Connolly.