In 1485 England was a small kingdom, the whole country consisted of a population of less than 3 million people, with 60,000 living in the capital, London.1 The Wars of the Roses was very much a recent trauma in the national memory. The country was a predominantly rural society, with local loyalties to local landowners – such as the Percies in Northumberland – taking precedence over national considerations. Noticeable regional differences varied in speech, diet, cloth, farming methods, the shape of church towers, and even the veneration of the saints. In Tudor Lincolnshire the Fens were yet to be drained, few roads were well-maintained and even they could be treacherous in heavy rains. Lincoln itself had been effected by the decline in the wool trade, and with a shrinking population, its size and prosperity were also decreasing.

A distinction was also rising among the aristocracy of the county and that of the royal court. In the regions, the minor nobility served the king as sheriffs, escheators and justices of the peace, or representing their county in parliament. The greater aristocracy, however, were looking for positions and influence at court; for themselves and their families. The Tudor court was a micro-world in itself. It set the standards in manners for the whole country. Service to the monarch was the primary concern. Most courtiers were related to each other, marriages were negotiated between the prominent families and service to the queen was the highest position a lady could aspire to.

At first glance you would think there was very little interaction between the nobility of Lincolnshire and the Tudor court. However, as we delve deeper we can see that, not only was there movement between the court and the county, it was not only one-sided, but fluid and travelling in both directions. When looking at this over the Tudor period – of over a hundred years of history – we notice the subtle changes in the interactions between the county and royal court, not only based on the progress of the time, but also the personalities involved and their personal experiences.

For some ladies, marrying into a member of the Lincoln aristocracy was a way of getting away from the glare of the court. For Elizabeth (Bessie) Blount, lady-in-waiting to Katherine of Aragon, a former mistress of Henry VIII and the mother of his illegitimate son Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond, it was the chance at a normal life. Born in 1500, Bessie Blount married Gilbert Tailboys in 1519, following her affair with Henry VIII and just months after the birth of the king’s son. The marriage was probably arranged by Henry as a ‘reward’ for Bessie. The couple settled on Gilbert’s family estates at Kyme in Lincolnshire. And despite being far from court, Bessie was not forgotten by the king. She continued to receive Henry’s favour, with various grants between 1522 and 1539 and New Years’ gifts throughout her life; in 1532 Henry sent her a gilt goblet with a cover weighing over 35 ounces.2

Bessie and Gilbert had three children together, Elizabeth, George and Robert, before his death in 1530. Gilbert Tailboys had settled part of his Lincolnshire estates on Elizabeth, giving her an annual income of £200 a year for life. Following his death, Bessie appears to have been happy to stay in Lincolnshire instead of returning to her Shropshire roots, or an unwelcoming royal court. In 1535 she married again, to the soldier Edward Fiennes de Clinton, 9th Baron Clinton and Saye, who was 12 years her junior. Although de Clinton had his family seat in Kent, they settled on Bessie’s Lincolnshire estates. They had three daughters together, Bridget, Katherine and Margaret, before Bessie died sometime before June 1541 (when Clinton remarried). While Elizabeth appears to have stayed away from court, Clinton’s marriage to the king’s former mistress brought him royal favour; he attended on the king at Calais and Boulogne in 1532 and acted as cup-bearer at the coronation of Anne Boleyn in 1533. Following the Lincolnshire Uprising of 1536, one of several rebellions which formed the Pilgrimage of Grace, Clinton was rewarded for staying loyal to the king – most Lincolnshire gentlemen had joined the rebellion – with the dissolved monastery of Sempringham.

Lincolnshire aristocratic families were often very closely related. Elizabeth and Edward’s daughter, Bridget, married Sir Robert Dymoke II, son of Sir Edward Dymoke and his wife Anne, who was the daughter of George Tailboys and the sister of Elizabeth’s first husband, Gilbert. The Dymoke family held Scrivelsby in Lincolnshire, through which tenure they were king’s champions; Sir Edward was champion at the coronations of Edward VI, Mary I and Elizabeth I. Sir Edward’s sister, Margaret, was born in Scrivelsby around 1500 and served several of Henry’s queens. After first marrying Richard Vernon of Haddon Hall, Derbyshire, she then married Sir William Coffin, Anne Boleyn’s Master of Horse. Margaret had been one of Queen Katherine of Aragon’s gentlewomen at the Field of Cloth of Gold and would also serve Henry VIII’s two subsequent queens.

Margaret, however, was not a favourite of Henry’s second queen, Anne Boleyn. She was one of the women who attended the disgraced queen in the Tower of London. Anne was recorded as complaining to her jailer, Sir William Kingston, “I think much unkindness in the king to put such about me as I never loved.”3 Margaret Dymoke, Lady Coffin slept on a pallet bed in the Queen’s bedchamber during her time in the Tower. In her desperation the queen confided in Margaret, unaware that she was acting as a spy for the state. Master Kingston reported to Thomas Cromwell that “I have everything told me by Mistress Coffin that she thinks meet for me to know.” 4 There is also a possibility that Margaret was not only a spy for Kingston, but also for the Imperial ambassador, Eustace Chapuys, who wrote “The lady who had charge of her [Anne] has sent to tell me in great secrecy that the concubine, before and after receiving the sacrament, affirmed to her, on the damnations of her soul, that she had never been unfaithful to the king.”5

Following Anne’s execution, Margaret joined the household of Queen Jane Seymour. Lady Coffin was in high favour in Jane Seymour’s establishment and acted as intermediary for several families who had hopes of placing a daughter in the royal household. Margaret remained with the queen until the end, and was among the mourners who attended the late queen’s body as it lay in state, keeping vigil and attending masses for her soul. Margaret was in the funeral procession that accompanied Jane’s body to her final resting place in St George’s Chapel, Windsor. She rode in the third carriage and bore Princess Mary’s train at the requiem mass; Mary was chief mourner and rode on a horse trapped with black velvet.6

There were several ladies associated with the Tudor court, who married into Lincolnshire society. The most famous must surely be one of Henry VIII’s own queens. Henry’s sixth wife, Kateryn Parr was the daughter of Sir Thomas Parr and his wife, Maud Green Parr, a lady-in-waiting to Katherine of Aragon. When Sir Thomas died while Kateryn was still a child, Maud took it on herself to arrange her daughter’s future. After a failed proposal to marry Katherine to the son of Lord Dacre, In 1529 Maud turned to another of her late husband’s relatives and arranged for Kateryn to marry Edward Burgh the eldest son of Sir Thomas Burgh, Baron Burgh of Gainsborough, Lincolnshire. Sir Thomas’s father, Sir Edward, had been declared a lunatic and Sir Thomas, himself, was renowned for his violent outbursts and wild rages (possibly due to an inherited mental instability in the family) and had a tyrannical control over his family. The first two years of the marriage, spent at Sir Thomas’s new Hall at Gainsborough (now known as the Old Hall), was an unhappy time for Kateryn. She wrote, regularly, to her mother of her unhappiness and it seems the situation was only resolved following a visit by Maud Parr, who persuaded Sir Thomas to allow Edward and Kateryn to move to their own, smaller, house at Kirton-in-Lindsey, a few miles outside of Gainsborough.

We do not know whether Edward was a sickly individual, or whether or not he succumbed to a sudden illness, but their happiness was short-lived, as he died in the spring of 1533, after only 4 years of marriage. Having no children, Kateryn was left with little from the marriage, and, with her mother having died the previous year, she was virtually alone in the world; possibly as a remedy to her isolation, Kateryn married her second husband, Lord Latimer, in the same year as she lost her first. There is no record that Kateryn served any of henry VIII’s queens. Her first appearance at court seems to be in 1542, when she became a lady-in-waiting in Mary Tudor’s household, before she caught the King’s eye. She does not seem to have forgotten her time with the Burgh family, however, and when she became queen Kateryn paid a pension from her own purse to her former sister-in-law, Elizabeth Owen, widow of her husband’s younger brother, Thomas. Poor Elizabeth had been accused of adultery by her domineering father-in-law, Sir Thomas, and her children were declared illegitimate by Act of Parliament in 1542.

Lord Burgh’s third surviving son, William, born in the early 1520s, would eventually succeed his father to the barony. He married Katherine Fiennes de Clinton, daughter of Edward Fiennes de Clinton – the future Earl of Lincoln – and Bessie Blount, demonstrating the interlinking relationships between the various great Lincolnshire families.

Where Kateryn Parr was linked to Lincolnshire before joining the royal court, others saw Lincolnshire as a place of retirement. Maria de Salinas was a lady-in-waiting and close friend to Katherine of Aragon; indeed, it seems that she came to England with the Spanish princess in 1501 for the marriage to Henry’s older brother, Arthur, Prince of Wales. Katherine and Maria were very close and by 1514 Caroz de Villagarut, ambassador of Katherine’s father, Ferdinand of Aragon, was complaining of Maria’s influence over the queen after she tried to persuade Katherine not to cooperate with the ambassador and encouraged the Queen to favour her English subjects.7 In June 1516 Maria married the largest landowner in Lincolnshire, William Willoughby, 11th Baron Willoughby de Eresby. The King and Queen paid for the wedding, which took place at Greenwich, and gave them a wedding gift of Grimsthorpe Castle, in Lincolnshire. The Queen even provided Maria with a dowry of 1100 marks.

Maria remained at court for some years after her wedding, and attended Katherine at the Field of Cloth of Gold in 1520. Henry VIII was godfather to Maria and William’s oldest son, Henry, who died in infancy. Another son, Francis, also died young and their daughter Katherine, born in 1519, would be the only surviving child of the marriage. Lord Willoughby died in 1526, and for several years afterwards Maria was embroiled in a legal dispute with her brother-in-law, Sir Christopher Willoughby, over the inheritance of the Willoughby lands. It seems William had settled some lands on Maria which were entailed to Sir Christopher. The dispute went to the Star Chamber and caused Sir Thomas More, the king’s chancellor and a prominent lawyer, to make an initial redistribution of some of the disputed lands.

This must have been a hard fight for a newly-widowed Maria, and the dispute threatened the stability of Lincolnshire itself, given the extensive lands involved. However, Maria attracted a powerful ally in Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk and brother-in-law of the King, who called on the assistance of Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, Henry’s first minister at the time, in the hope of resolving the situation. Suffolk had managed to obtain the wardship of Katherine Willoughby in 1529, intending her to marry his eldest son and heir Henry, Earl of Lincoln, and so had a vested interest in a favourable settlement for Maria. This interest became even greater following the death of Mary Tudor, Suffolk’s wife and Henry VIII’s sister, in September 1533, when only three months later the fifty-year-old Duke of Suffolk married fourteen-year-old Katherine, himself. Although Suffolk pursued the legal case with more vigour after the wedding, a final settlement was not reached until the reign of Elizabeth I. Suffolk eventually became the greatest landowner in Lincolnshire and, despite the age difference, the marriage does appear to have been successful. Katherine served at court, in the household of Henry VIII’s 6th and last queen, Katherine Parr. She was widowed in 1545 and lost her two sons – and heirs – by the Duke, Henry and Charles, to the sweating sickness, within hours of each other in 1551.

As duchess of Suffolk, Katherine was a stalwart of the Protestant learning and used her position to introduce Protestant clergy to Lincolnshire, even inviting Hugh Latimer to preach at Grimsthorpe Castle. It was she and Sir William Cecil who persuaded Kateryn Parr to publish her book, The Lamentacion of a Sinner in 1547, demonstrating her continuing links with the court despite her first husband’s death.

Following the death of her sons by Suffolk, Katherine no longer had a financial interest in the Suffolk estates, which went to the heirs of Mary Tudor, Henry VIII’s sister. However, Katherine still had her own Willoughby estates to look after and it was in order to safeguard these that Katherine married her gentleman usher, Richard Bertie. The couple had a difficult time navigating the religious tensions of the age and even went into exile on the Continent during the reign of the Catholic Queen, Mary I. Following their return to England, on Elizabeth’s accession, Katherine resumed her position in Tudor society; her relations with the court, however, were strained by her tendency towards Puritan learning. She used her position in Lincolnshire and extensive patronage to help disseminate the Puritan teachings. The records of Katherine’s Lincolnshire household show that she employed Miles Coverdale – a prominent critic of the Elizabethan church – as tutor to her two children by Bertie; Susan and Peregrine.8 Unfortunately, Katherine died after a long illness, on 19th September 1580 and was buried in her native Lincolnshire, in Spilsby Church.

Katherine’s mother, Maria de Salinas, Lady Willoughby, had died in 1539 and had stayed loyal to her mistress, Katherine of Aragon, throughout her married life and widowhood. Indeed, when Katherine was reported to be dying at Kimbolton Castle, Maria applied for a license to visit her ailing mistress, but was refused by Sir Thomas Cromwell, the King’s chief minister at the time. Despite this setback, Maria set out from London to visit Katherine at the beginning of January 1536 and contrived to get herself admitted by Sir Edmund Bedingfield by claiming a fall from her horse meant she could travel no further. According to Sarah Morris and Nathalie Grueninger, Katherine and Maria spent hours talking in their native Castilian; the former queen died in Maria’s arms on 7th January 1536. Katherine of Aragon was buried in Peterborough Cathedral on 29th January, with Maria and her daughter, Katherine, attending the funeral.9

The composition of the Tudor court changed under Elizabeth I. The new queen valued loyalty and most positions went to members of her extended family; the Howards and Careys among them. Throughout the forty-five years of Elizabeth’s reign, only twenty-eight women were appointed to salaried positions in the privy Chamber. Positions in the Bedchamber, Privy Chamber and Presence Chamber were highly sought after and mainly given to ladies from the same families, who were assigned positions based on their social status. The senior positions were those of the Chief and Second Gentlewoman of the Privy Chamber, these were followed by the Ladies of the Bedchamber, the Ladies of the Privy Chamber and the Ladies of the Presence Chamber, in descending order. Unmarried young ladies were given positions as maids of honour and were supervised by the Mother of the Maids.

Elizabeth Fitzgerald, a great granddaughter of Elizabeth Woodville, had entered Princess Elizabeth’s household in 1539, possibly as a maid of honour but ostensibly to be raised alongside her cousin. She was only nine or ten years old at the time. Elizabeth Fitzgerald had been born in Ireland in about 1528 and was the second daughter of Gerald Fitzgerald, 9th Earl of Kildare. Her mother was Lady Elizabeth Grey, daughter of Sir Thomas Grey, Marquess of Dorset and only surviving son of Elizabeth Woodville, Edward IV’s queen. Elizabeth Fitzgerald must have been quite a beauty as Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, wrote a sonnet, From Tuscan cam my ladies worthi race in praise of her as his Fair Geraldine; Bewty of kind, her vertues from above; Happy ys he that may obtaine her love.10

In 1542 Elizabeth married her first husband, Sir Anthony Browne, but he died in 1548 and their two sons died in infancy. In 1552 she married again, this time to Edward Fiennes de Clinton, 9th Baron Clinton and Saye; the same Baron Clinton who had married Bessie Blount in 1535. Clinton had remarried in 1541, after Bessie’s death, to Ursula, daughter of William, 7th Baron Stourton; Ursula was a niece of John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland during the reign of Edward VI. She died in 1551 and Edward married Elizabeth the following year. Sir Edward Fiennes de Clinton had led a very successful military career and in May 1550 he had been appointed a privy councillor and lord high admiral of England. He was made a knight of the garter in April 1551 and, later in the same year, was given the former Howard property of Tattershall Castle in Lincolnshire, which he made his principal residence. Clinton was an adept political survivor; after being involved in the plot to put Jane Grey on the throne he was imprisoned for a short while, but managed to win Queen Mary’s trust and was active in her military campaigns. With the accession of Elizabeth I, Clinton was appointed a privy councillor and his wife, Elizabeth Fiennes de Clinton, was appointed Gentlewoman of the Privy Chamber ‘without wages’ (this indicated her high-born status, as salaried members were drawn from the lower ranks of the nobility).

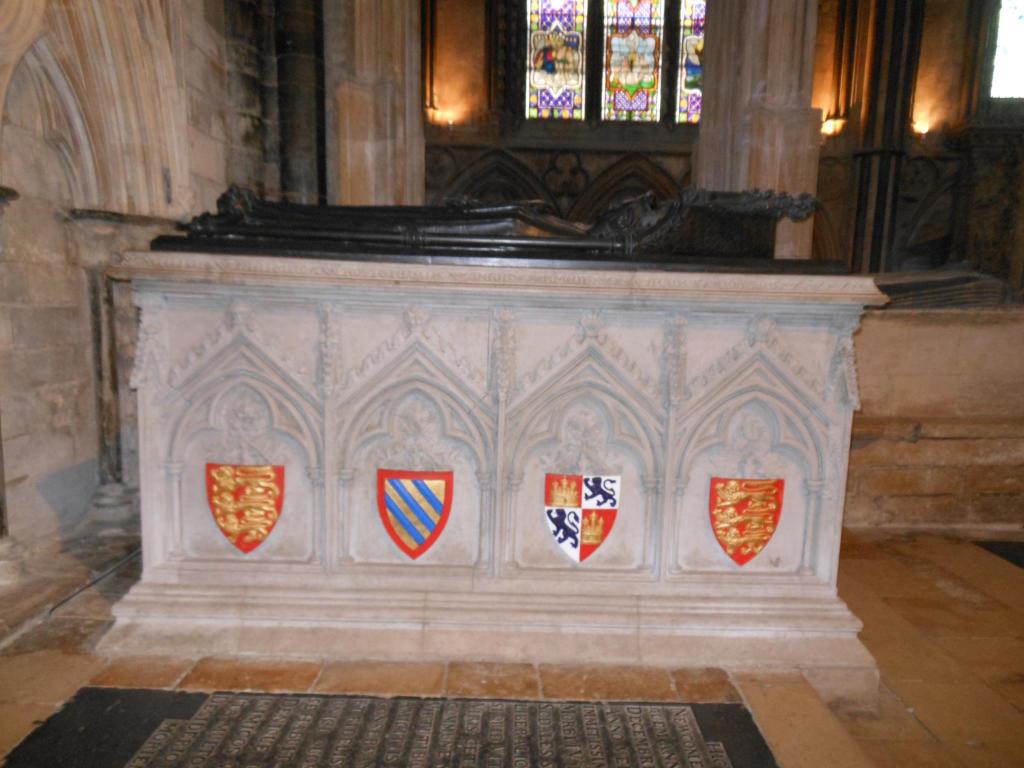

In 1572 Baron Clinton was rewarded for his service with the earldom of Lincoln. Elizabeth had practically been raised with the new queen since she was ten years old and was able to use her influence at court to benefit her family, affecting the restoration of the Fitzgeralds to their blood and lineage, which they had lost when Elizabeth was a child. Suits made to Elizabeth as Countess of Lincoln demonstrate that she was believed to have influence with the queen, who she served until 1585. Edward trusted his wife considerably, and made her executor of his will, bequeathing Semprigham to Elizabeth, and Tattershall to his eldest son, Henry (his son by Ursula). Edward, Earl of Lincoln, died in 1585 and just before his father’s death, his son Henry had written to William Cecil, Lord Burghley, in an attempt to overturn his father’s will, accusing Elizabeth of attempting to deprive him of his inheritance, and of maligning him to the queen. However, Henry’s tactic failed and the will was confirmed in 1587. Elizabeth herself appears to have withdrawn from court following her husband’s death and when she died in March 1589 was laid to rest beside her husband in the Lincoln Chapel of St George’s Chapel Windsor.

The court and society were both in a state of change during Elizabeth’s reign. Local Lincolnshire lords, such as the Burghs of Gainsborough, were increasingly absentee landlords, preferring to stay in their southern properties closer to the royal court and leaving their estates to run themselves. The Burghs increasingly resided mainly at their residence in Surrey, Sterborough Castle. Lord Thomas de Burgh fell heavily into debt in service of the Queen and was in failing health when his wife, Lady Frances begged Queen Elizabeth that he be relieved of his position as Governor of the Brill in the Netherlands. Sir Robert Sydney is quoted as saying in November 1595 “God send lady… better success than my lady Borow [Burgh], whose desire was absolutely denied and the Queen took it very ill that in such time he could desire to be from this government.”11 When Lord Burgh died in 1597 he asked the Queen, in his will, to protect his wife and family, who were now living in poverty due to his having spent his patrimony in Elizabeth’s service. The Queen, however, devised a a way of avoiding the duty imposed upon her, by requesting that whoever was appointed to Lord Burgh’s now vacant post, as Governor of Brill, should give £500 a year to his widow for her maintenance.

Religious divisions were becoming more pronounced as Queen Elizabeth’s reign advanced, not only between Catholicism and Protestantism, but within Protestantism itself. With the encouragement of Katherine Willoughby, Duchess of Suffolk, ministers with Puritan leanings had been appointed to various churches throughout Lincolnshire. Several of the Pilgrim Fathers, who sailed to America on the Mayflower, would come from the region, including William Brewster and William Bradford. Families with strong ties to service at the Tudor court, such as the Burghs of Gainsborough, were moving south, closer to London and the person of the Queen, while other families were moving north. The Old Hall at Gainsborough was sold to William Hickman, a wealthy merchant who was the grandson of Sir William Locke, Henry VIII’s Royal Mercer, and the son of Lady Rose Hickman.

According to Lady Rose her father, Sir William Locke, a merchant with strong links to Antwerp, had smuggled ‘herectic’ Protestant writings from abroad for Queen Anne Boleyn herself. Lady Rose had long been familiar with the new learning and wrote in 1610: “My mother in the dayes of King Henry the 8th came to some light of the gospel by means of some English books sent privately to her by my father’s factor from beyond the sea: where upon she used to call me with my 2 sisters into her chamber to read to us out of these same good books very privately for feare of troble because these good books were then accepted hereticall…”12

The Hickman family had become known for their Puritan leanings; Puritans were those who wanted the ‘purer’ church as envisaged in the reign of Edward VI, rather than the compromise established by Elizabeth I. In 1593, in order to curb the activities of such religious dissidents, Elizabeth I’s government had approved the ‘Act Against Puritans’, whereby it became illegal to become a Puritan or encourage others to that tendency. As a result, official appointments at court, for those known to have Puritan connections, suddenly dried up. Lady Rose’s son Walter, deeply entrenched in court circles and an old hand at brokering appointments for friends and family (usually with a financial incentive) discovered the implications of the new stance in 1594. The Cecil Papers show that Walter was refused when he applied for the position of Receiver of the Court of Wards for his brother William, despite offering an inducement of £1,000.13 The increasing hostility towards Puritans, and the possibility of escalating religious persecution, may well have persuaded William to move his family north; away from the prying eyes of the authorities and into Lincolnshire, a county with strong Puritan leanings thanks to the efforts of Katherine Willoughby, Duchess of Suffolk.

In the early years of the Tudor dynasty, the counties of Lincolnshire and Yorkshire were still greatly associated with the old Yorkist dynasty. Henry VII made a progress through the counties only a year after his accession, keeping Easter 1486 at Lincoln and making a great show of regal pomp. His son, Henry VIII, also saw the need to show himself to his northern subjects. Following the defeat of the Pilgrimage of Grace and its forebear, the Lincolnshire Rising, Henry made a great progress through Lincolnshire and Yorkshire. He spent several days at Gainsborough Old Hall in August 1541, holding meetings of the Privy Council there on the 14th, 15th and 16th of August. At Lincoln Henry and his young queen, Katherine Howard, made a great show of royal majesty; “The King and Queen came riding into their tent, which was pitched at the furthest end of the liberty of Lincoln, and there shifted their apparel, from green and crimson velvet respectively, to cloth of gold and silver…”14

Henry VIII’s children, however, did not venture north. Although Elizabeth I had intended to visit York at various points in her reign, she stayed within the Home Counties, venturing no further north than East Anglia. This may well have contributed to the changing nature of Tudor Society in Lincolnshire, where the influence from court circles appears to have waned as the years progressed. Lincolnshire towns, such as Gainsborough and Boston, provided such families with the opportunities of, to some extent, religious freedom while also allowing them to continue with their merchant activities, due to navigable rivers that would take goods to the East coast ports and on to the Continent. Whereas those who saw the government as a hindrance to their personal liberties ventured away further from the centre of power; those who saw their futures in the person of the monarch, and whose duties at the Tudor Court were taking up more and more of their time, saw the need to move closer to London and the centre of power,

*

Footnotes:

1 Neville Williams, The Life and Times of Henry VII; 2 Beverley A Murphy, Bastard Prince: Henry VIII’s Lost Son; 3 Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, of Henry VIII, Volume 10, note 797; 4 Ibid; 5 Ibid; 6 Letters and Papers Volume 12, Part 2, note 1600; 7 Retha M. Warnicke, Oxforddnb.com; 8 Susan Wabuda, Oxforddnb.com; 9 Sarah Morris and Natalie Grueninger, In the Footsteps of the Six Wives of Henry VIII; 10 H. Howard [earl of Surrey], Poems, ed. E. Jones (1964); 11 Quoted by Sue Allan in A Guide to Gainsborough Old Hall; 12 Religion and politics in mid-Tudor England through the eyes of an English Protestant Woman: the Recollections of Rose Hickman; 13 Quoted by Sue Allan in A Guide to Gainsborough Old Hall; 14 Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, of Henry VIII, 1541

Images;

Courtesy of Wikipedia except Grimsthorpe Castle and Gainsborough Old Hall, which are ©Sharon Bennett Connolly

Sources:

John Leland Leland’s Itinerary in England and Wales 1535-43 edited by L Toulmin Smith (1906-10); Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, of the Reign of Henry VIII 1509-47 edited by JS Brewer, James Gairdner and RH Brodie, HMSO London 1862-1932; Privy Purse Expenses of King Henry VIII from November MDXIX to December MDXXXII edited by Sir Nicholas Harris Nicolas 1827; Religion and politics in mid-Tudor England through the eyes of an English Protestant Woman: the Recollections of Rose Hickman edited by Maria Dowling and Joy Shakespeare; Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research, 1980 & 1982; Oxforddnb.com; A Guide to Gainsborough Old Hall by Sue Allan; The Life and Times of Henry VII by Neville Williams; Bastard Prince: Henry VIII’s Lost Son by Beverley A Murphy; In the Footsteps of the Six Wives of Henry VIII by Sarah Morris and Natalie Grueninger; H. Howard [earl of Surrey], Poems, ed. E. Jones (1964); The Earlier Tudors by J.D. Mackie; Religion and politics in mid-Tudor England through the eyes of an English Protestant Woman: the Recollections of Rose Hickman; Tudorplace.com; Elizabeth’s Women by Tracy Borman; England Under the Tudors by Arthur D Innes; Henry VIII: King and Court by Alison Weir; In Bed with the Tudors by Amy Licence; Ladies-in-Waiting: Women who Served at the Tudor Court by Victoria Sylvia Evans; The Six Wives and Many Mistresses of Henry VIII: The Women’s Stories by Amy Licence.

*

My Books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

OUT NOW! Heroines of the Tudor World

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. These are the women who made a difference, who influenced countries, kings and the Reformation. In the era dominated by the Renaissance and Reformation, Heroines of the Tudor World examines the threats and challenges faced by the women of the era, and how they overcame them. From writers to regents, from nuns to queens, Heroines of the Tudor World shines the spotlight on the women helped to shape Early Modern Europe.

Heroines of the Tudor World is now available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK.

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how Empress Matilda and Matilda of Boulogne, unable to wield a sword themselves, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It shows how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other. Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon. Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org.

Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

© 2021 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS