Joanna of England was born in October 1165, the 7th child and youngest daughter of Henry II of England and Eleanor of Aquitaine. Ten years younger than her eldest brother, Henry the Young King, she was born at a time when their parents’ relationship was breaking down; her mother would eventually go to war against her husband, before being imprisoned by him for the last 16 years of Henry’s reign.

Born at Angers Castle in Anjou, Christmas 1165 was the first ever Christmas her parents spent apart; with Henry still in England dealing with a Welsh revolt, it would be several months before he met his new daughter for the first time. Although Joanna spent much of her childhood at her mother’s court in Poitiers, she and her younger brother, John, spent sometime boarding at the magnificent Abbey of Fontevraud. Whilst there Joanna was educated in the skills needed to run a large, aristocratic household and in several languages; English, Norman French and rudimentary Latin.

When Eleanor and her sons rebelled in 1173, Henry II went to war against his wife. When she was captured – wearing men’s clothes – she was sent to imprisonment in England. Joanna joined her father’s entourage and frequently appeared at Henry’s Easter and Christmas courts.

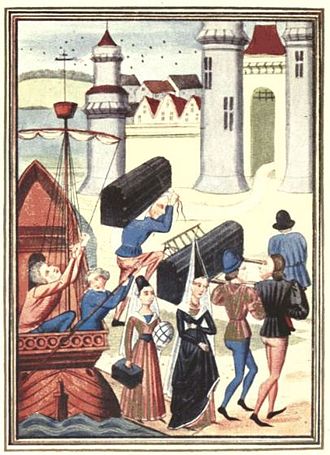

3 years later, Eleanor was allowed to travel to Winchester to say ‘goodbye’ to her youngest daughter, who had been betrothed to King William II of Sicily. Provided with a trousseau, probably similar to that of her sister Matilda on her marriage to Henry the Lion, Joanna set out from Winchester at the end of August 1176; escorted by Bishop John of Norwich and her uncle, Hamelin de Warenne.

Joanna’s entourage must have been a sight to see. Once on the Continent, she was escorted from Barfleur by her brother Henry, the Young King. Her large escort was intended to dissuade bandit attacks against her impressive dowry, which included fine horses, gems and precious metals. At Poitiers, Joanna was met by another brother, Richard, who escorted his little sister to Toulouse in a leisurely and elegant progress.

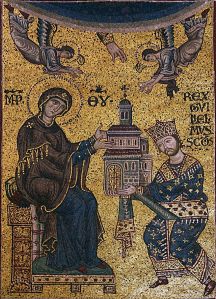

Having finally reached Sicily 12-year-old Joanna was married to 24-year-old William on 13th February 1177, in Palermo Cathedral. The marriage ceremony was followed by her coronation as Queen of Sicily. Joanna must have looked magnificent, her bejewelled dress cost £114 – not a small sum at the time.

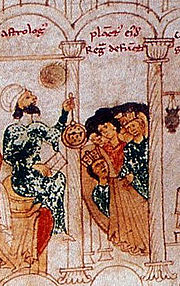

Sicily was an ethnically diverse country; William’s court was composed of Christian, Muslim and Greek advisers. William himself spoke, read and wrote Arabic and, in fact, kept a harem of both Christian and Muslim girls within the palace. Although she was kept secluded, it must have been a strange life for a young girl, partly raised in a convent.

Joanna and William only had one child, Bohemond, Duke of Apulia, who was born – and died – in 1181. And when William died without an heir in November 1189, Joanna became a pawn in the race for the succession. William’s aunt, Constance was the rightful heir, but she was married to Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor and many feared being absorbed into his empire. William II’s illegitimate nephew, Tancred of Lecce, seized the initiative. He claimed the throne and, in need of money, imprisoned Joanna and stole her dowry and the treasures left to her by her husband.

Who knows how long Joanna would have remained imprisoned, if it had not been for her brother’s eagerness to go on Crusade? Having gained the English throne in 1189 Richard I – the Lionheart – had wasted no time in organising the Third Crusade and arrived at Messina in Sicily in September 1190.

Richard demanded Joanna’s release; and fearing the Crusader king’s anger Tancred capitulated and freed Joanna, paying 40,000 ounces of gold towards the Crusade in fulfilment of William II’s promise of aid.

Described as beautiful and spirited, Joanna had been Queen of Sicily for 13 years and it seems that, while at her brother’s court, she caught the eye of Richard’s co-Crusdaer, King Philip II of France. Richard was having none of it and moved Joanna to the Priory of Bagnara on the mainland, out of sight and hopefully out of mind.

Richard stayed in Sicily for sometime, negotiating a treaty with Tancred which would recognise him as rightful king of Sicily in return for the remainder of Joanna’s dowry and 19 ships to support the Crusade. He was also waiting for his bride, Berengaria of Navarre, to catch up with him.

During Lent of 1191 Joanna had a brief reunion with her mother Eleanor of Aquitaine when she arrived in Sicily, having escorted Richard’s bride. Joanna became Berengaria’s chaperone and they were lodged together at Bagnara, like ‘two doves in a cage’.

Unable to marry in the Lenten season, Richard sent Joanna and Berengaria on ahead of the main army, and departed Sicily for the Holy Land.

The Royal ladies’ ship was driven to Limassol on Cyprus by a storm. After several ships were crippled and then plundered by the islanders, the ruler of Cyprus, Isaac Comnenus, tried to lure Joanna and Berengaria ashore. Richard came to the rescue, reduced Cyprus in 3 weeks and clamped Comnenus in chains (silver ones apparently). Lent being over, Richard and Berengaria were married, with great pomp and celebration, before the whole party continued their journey to the Holy Land, arriving at Acre in June 1191.

Joanna’s time in the Holy Land was spent in Acre and Jaffa, accompanying her sister-in-law and following – at a safe distance – behind the Crusading army. She spent Christmas 1191 with Richard and Berengaria, at Beit-Nuba, just 12 miles from Jerusalem. However, although he re-took Acre and Jaffa, Richard fell out with his allies and was left without a force strong enough to take Jerusalem.

In attempts to reach a political settlement with the Muslim leader, Saladin, Richard even offered Joanna as a bride for Saladin’s brother. His plans were scuppered, however, when Joanna refused outright to even consider marrying a Muslim, despite the fact Richard’s plan would have seen her installed as Queen of Jerusalem.

When a 3-year truce was eventually agreed with Saladin, Joanna and Berengaria were sent ahead of the army, to Sicily and onto Rome where they were to await Richard’s arrival. Richard, however, never made it; falling into the hands of Duke Leopold of Austria, he was handed over to his enemy, the Holy Roman Emperor.

With Richard imprisoned, Berengaria and Joanna arrived back in Poitiers. Berengaria herself set out to help raise the ransom money for Richard’s release, which finally came about in February 1194.

Joanna spent the next few years at her mother’s and brother’s courts, her wealth having been squandered by Richard’s Crusade. But at the age of 31 she was proposed as a bride for Raymond VI, Count of Toulouse. Her title as Queen of Sicily would give him greater prestige while bringing the County of Toulouse into the Plantagenet fold, a long-time aim of Eleanor’s.

3-times married Raymond does not seem to have been ideal husband material; he had been excommunicated for marrying his third wife whilst still married to his second. And he now repudiated wife number 3, confining her to a convent, in order to marry Joanna. Despite such a colourful history, the wedding went ahead and Joanna and Raymond were married in Rouen in October 1196, with Queen Berengaria in attendance.

Although not a happy marriage Joanna gave birth to a son, Raymond, in around 1197 and a daughter, possibly called Mary, in 1198. Little is known of Mary, and it is possible she died in infancy. Raymond succeeded his father as Raymond VII Count of Toulouse, and married twice.

Raymond VI was not a popular Count of Toulouse and while he was away in the Languedoc, in 1199, dealing with rebel barons, Joanna herself tried to face down her husband’s enemies. She laid siege to a rebel stronghold at Cassee. Mid-siege, however, her troops turned traitor and fired the army’s camp – Joanna managed to escape, but was probably injured.

A pregnant Joanna was then trying to make her way to her brother Richard when she heard of his death. She diverted course and finally reached her mother at Niort. Hurt, distressed and pregnant, Eleanor sent her to Fontevraud to be looked after by the nuns.

With no allowance from her husband, Joanna returned to her mother and brother – King John – in Rouen in June 1199, pleading poverty; Eleanor managed to persuade John to give his sister an annual pension of 100 marks.

Joanna’s last few months must have been a desperate time. Too ill to travel and heavily pregnant, she remained at Rouen. In September, King John gave her a lump sum of 3,000 marks, to dispose of in her will; she specifically mentioned a legacy towards the cost of a new kitchen at Fontevraud and asked Eleanor to dispose of the remainder in charitable works for the religious and the poor.

Knowing she was dying, Joanna became desperate to be veiled as a nun at Fontevraud; a request normally denied to married women – especially when they were in the late stages of pregnancy. However, seeing how desperate her daughter was, Eleanor sent for Matilda, the Abbess of Fontevraud but, fearing the Abbess would arrive too late, she also asked Hubert Walter, the Archbishop of Canterbury, to intervene. The Archbishop tried to dissuade Joanna, but was impressed by her fervour and convened a committee of nuns and clergy; who agreed that Joanna must be ‘inspired by heaven’.

In Eleanor’s presence, the Archbishop admitted Joanna to the Order of Fontevraud. Joanna was too weak to stand and died shortly after the ceremony; her son, Richard, was born a few minutes later and lived only long enough to be baptised. She died on 4 September 1199, a month short of her 34th birthday.

Joanna and her baby son were interred together at Fontevraud, the funeral cortege having been escorted there by Eleanor of Aquitaine and King John.

The Winchester Annalist said of Joanna, that she was;

a woman whose masculine spirit overcame the weakness of her sex

Winchester Annalist quoted in Oxforddnb.com

*

Do have a listen to our recent episode of A Slice of Medieval in which Derek and I chat with Catherine Hanley about her biography of Joanna, Lionessheart.

Pictures taken from Wikipedia

References: Mike Ashley The Mammoth Book of Kings & Queens; Alison Weir Britain’s Royal Families, the Complete Genealogy; Robert Bartlett England Under the Norman and Angevin Kings; Alison Weir Eleanor of Aquitaine, by the Wrath of God, Queen of England; Douglas Boyd Eleanor, April Queen of Aquitaine; bestofsicily.com; Oxforddnb.com; britannica.com; geni.com; royalwomenblogspot.co.uk; medievalqueens.com.

*

My books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

Out now: Scotland’s Medieval Queens

Scotland’s history is dramatic, violent and bloody. Being England’s northern neighbour has never been easy. Scotland’s queens have had to deal with war, murder, imprisonment, political rivalries and open betrayal. They have loved and lost, raised kings and queens, ruled and died for Scotland. From St Margaret, who became one of the patron saints of Scotland, to Elizabeth de Burgh and the dramatic story of the Scottish Wars of Independence, to the love story and tragedy of Joan Beaufort, to Margaret of Denmark and the dawn of the Renaissance, Scotland’s Medieval Queens have seen it all. This is the story of Scotland through their eyes.

‘Scotland’s Medieval Queens gives a thorough grounding in the history of the women who ruled Scotland at the side of its kings, often in the shadows, but just as interesting in their lives beyond the spotlight. It’s not a subject that has been widely covered, and Sharon is a pioneer in bringing that information into accessible history.’ Elizabeth Chadwick (New York Times bestselling author)

Available now from Amazon and Pen and Sword Books

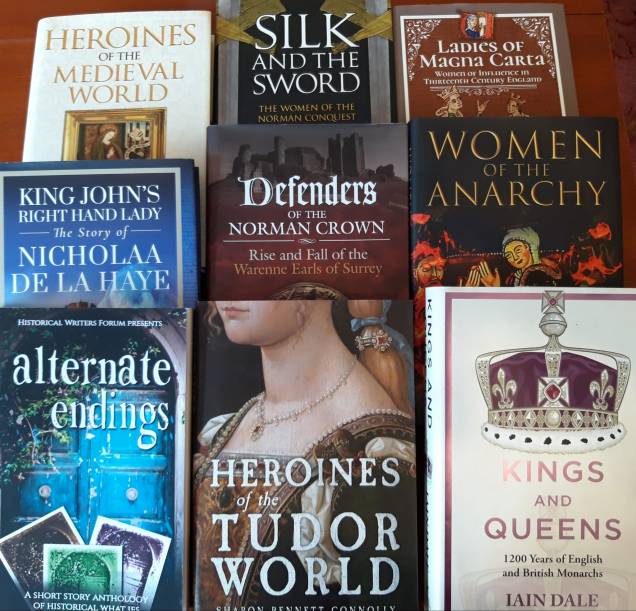

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. Heroines of the Tudor World is now available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how Empress Matilda and Matilda of Boulogne, unable to wield a sword themselves, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It shows how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other. Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org. Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Elizabeth Chadwick, Helen Castor, Ian Mortimer, Scott Mariani and Bernard Cornwell and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

Every episode is also now available on YouTube.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online store.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter, Threads, Bluesky and Instagram.

©2015 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS