The Woodville family are synonymous with the Wars of the Roses. While much has been published on the family as a whole, especially Elizabeth, wife of Edward IV, Anthony Woodville – the favourite sibling of Elizabeth – has been largely overlooked by history. He is famed for his arrest and execution in June 1483, but there is much more to learn from his life. Woodville was a man with an important cultural role. He was a knight, had a successful jousting career, and worked with the printing pioneer William Caxton. He was the printer’s only long-lasting patron in England and acted as translator for him, using the books printed by Caxton to educate Edward, Prince of Wales, the future Edward V.

This book seeks to bring Anthony Woodville out of the shadows of history, giving him the recognition he deserves and challenging the negative perceptions around him by investigating his personality and personal achievements in military, diplomatic and literary capacities.

I have always had the impression that Anthony Woodville would have stood out in any period of history. A Renaissance man, he championed the arts, patronised the printing press, was a renowned jouster and so well respected by his king that he was entrusted with the education and upbringing of the Prince of Wales – the future King Edward V.

I do think Woodville would have stood out in any generation, but it didn’t hurt that his sister was Elizabeth Woodville, Queen of England.

Anthony Woodville, as the queen’s brother, was at the centre of events during the reign of Edward IV. He accompanied his brother-in-law into exile when Henry VI briefly reclaimed the throne in 1470-71. He appeared in tournaments to celebrate the marriage of the king’s sister, Margaret, to the future duke of Burgundy. He was a poet and writer and was a patron of William Caxton, the man who brought the printing press to England. Caxton printed and published Woodville’s English translation of The Dictes and Sayings of the Philosophers. So why is there not a larger body of work on him?

Danielle Burton has rectified this omission with her fascinating, in-depth study, Anthony Woodville, Sophisticate or Schemer? She delves deep into Woodville’s life, family, loves and career.

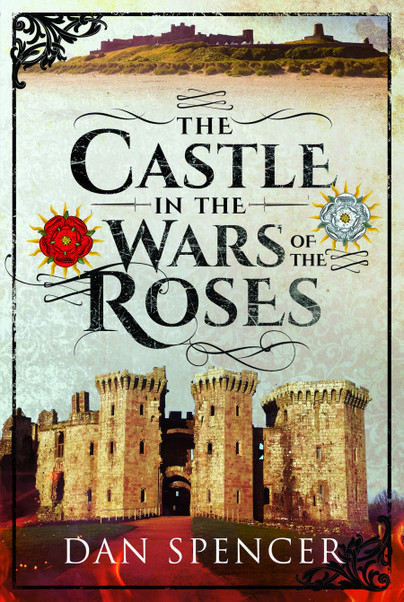

The Woodville family are often viewed as grasping and power hungry. This is true of some of the family members, particularly Thomas Grey, Marquess of Dorset, who was the eldest son of Anthony’s sister Elizabeth by her first marriage to John Grey. However, Anthony, while of course benefitting from the advancement of his sister to the status of queen, notably avoided meddling wherever possible. His interests in piety, tutoring Edward, the Prince of Wales, jousting, and translating books let him play a background role in the Wars of the Roses.

While Anthony Woodville may have been a secondary figure in political terms, it is clear that he had a significant part in transforming English culture, especially through his patronage of William Caxton, as well as his tutelage of Edward. Prince of Wales, who resided at Ludlow Castle for around ten years. According to Dominic Mancini, and Italian visitor who stayed in England between late summer 1482 and July 1483, Anthony Woodville was ‘always considered a kind, serious and just man’ who was ‘tested by every vicissitude of life.’ It was for this reason that he had been entrusted with the ‘care and direction’ of the prince. Further to Mancini’s description of Anthony, he purposefully contrasts his character with that of other Woodvilles, who were ‘detested by the nobles.’ There is a certain amount of truth in this, for unlike some other family members Anthony preferred to stay away from court life, favouring more academic and religious pursuits.

As a debut work, Anthony Woodville, Sophisticate or Schemer? is very impressive. It is clear that Danielle Burton has done her research, thoroughly, using primary sources where possible. She uses her extensive knowledge of Anthony Woodville to suggest reasons for his actions and to fill in the gaps of our knowledge, clearly indicating her theories and supporting arguments. There are some minor errors, which other reviewers have highlighted, but nothing that changes the thrust of the arguments nor detracts from the enjoyment of reading. They certainly do not devalue the biography as a whole and are more a sign of the writer’s inexperience of the editing process. I certainly would not expect it to put a reader off.

I suspect Anthony Woodville is Danielle’s historical crush, but this adds to the passion in her retelling of his story. We all fall in love with our subjects, just a little bit. You cannot spend years studying a person without doing so.

Danielle Burton’s arguments are balanced and do not present Anthony Woodville and some flawless super hero. Rather, he is an accomplished knight who had his flaws and would often look to his own advantage. Who wouldn’t? He was, however, loyal to Edward IV and his nephew, Edward V. And, having been the younger Edward’s guardian since his early years, was probably a great influence on the teenage king. This would Explain why Richard, Duke of Gloucester – the future Richard III – saw him as a threat. In Anthony Woodville, Sophisticate or Schemer? Danielle looks into the events of 1483 in great detail, examining the relationship between Richard and Anthony and analysing what went wrong and why. Anthony Woodville’s execution at Pontefract Castle is a tragic consequence of the power struggle that followed the death of Edward IV and accession of Anthony’s charge, Edward V.

All in all, Anthony Woodville, Sophisticate or Schemer? by Danielle Burton is a much-needed addition to the study of the Wars of the Roses, highlighting a man of great influence who is often overlooked in favour of his royal contemporaries. It is an impressive piece of work.

Listen to: Danielle Burton talking about Anthony Woodville, Sophisticate or Schemer? with myself and Derek Birks on our podcast, on A Slice of Medieval.

To Buy the Book: Anthony Woodville, Sophisticate or Schemer? is available from Amazon or direct from Amberly Publishing.

About the Author: Danielle Burton has had a keen interest in the Wars of the Roses from a young age, including being a member of the Richard III Society since the age of 9. She has presented aspects of her research into the life of Anthony Woodville at various academic conferences, and works in the heritage sector.

*

My Books:

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

Out Now! Women of the Anarchy

Two cousins. On the one side is Empress Matilda, or Maud. The sole surviving legitimate child of Henry I, she is fighting for her birthright and that of her children. On the other side is her cousin, Queen Matilda, supporting her husband, King Stephen, and fighting to see her own son inherit the English crown. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how these women, unable to wield a sword, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It show how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other.

Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK.

Coming on 15 June 2024: Heroines of the Tudor World

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. These are the women who made a difference, who influenced countries, kings and the Reformation. In the era dominated by the Renaissance and Reformation, Heroines of the Tudor World examines the threats and challenges faced by the women of the era, and how they overcame them. From writers to regents, from nuns to queens, Heroines of the Tudor World shines the spotlight on the women helped to shape Early Modern Europe.

Heroines of the Tudor World is now available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK.

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

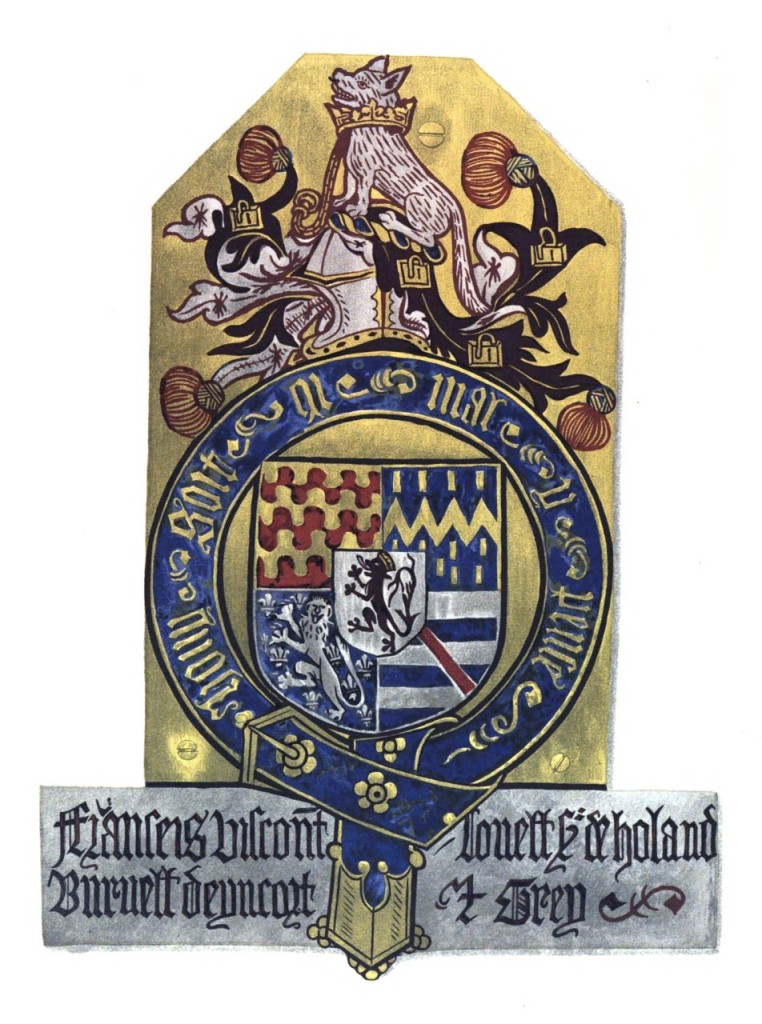

King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. It is is available from King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops or direct from Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon. Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org.

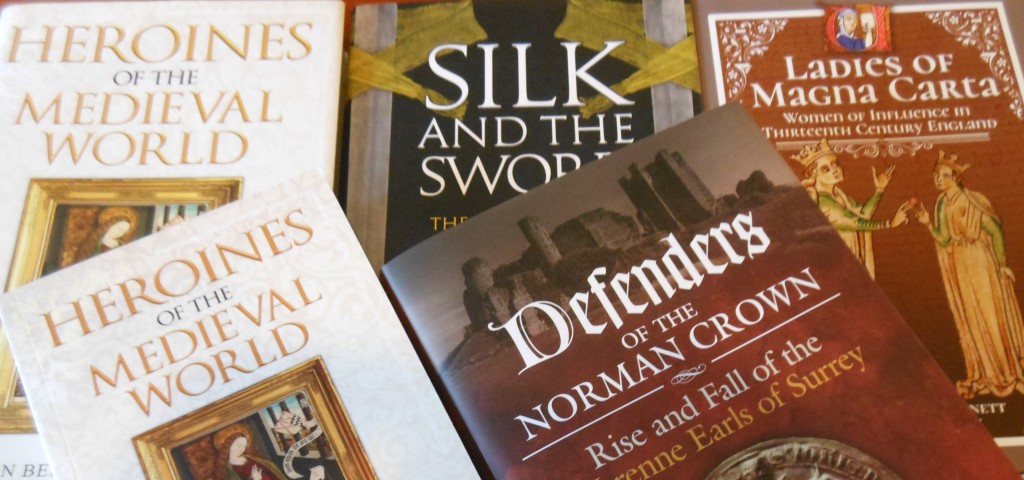

Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell and Elizabeth Chadwick, and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

*

©2024 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS