When watching Outlaw King a couple of weeks ago, I was disappointed to see that they had omitted the stories of Robert the Bruce’s sister, Mary, and the woman who crowned him, Isabella MacDuff, Countess of Buchan. And yet, they managed to keep the punishment Edward I meted out to them, but inflicted it on Robert the Bruce’s wife, Elizabeth de Burgh, instead. In a great example of dramatic licence, they also insisted on retelling the age-old fallacy that the cage was hung from the castle walls, exposing the poor woman to ridicule and the elements.

While it is necessary to change stories, and limit the number of protagonists in a movie, in order to avoid confusion, produce a fabulous story and, probably, keep down costs, I thought it a shame that the remarkable stories of Mary and Isabella were ignored, or rather circumvented for the dramatic benefit of the movie.

We know very little of Mary Bruce. She was a younger sister of King Robert, probably born around 1282. A younger daughter of Robert de Brus, 6th Earl of Annandale, and Marjorie, Countess of Carrick in her own right. It may be that she took care of her brother’s daughter, Marjorie, after Robert’s first wife, Isabella of Mar, died giving birth to the baby girl.

Her story has long been intertwined with that of her brother.

From that fateful moment in Greyfriars Church in Dumfries when Robert the Bruce – or one of his men – is said to have stabbed to death John Comyn, his rival to the Scottish throne, it was a race against time for Robert to establish himself as king. Whether Comyn’s death was accidental or murder, we’ll probably never know. Almost immediately, Robert made the dash for Scone, hoping to achieve his coronation before the Christian world erupted in uproar over his sacrilege. An excommunicate could not be crowned. His sisters Christian and Mary accompanied him to Scone Abbey, as did his wife Elizabeth and daughter Marjorie. The Stone of Scone was the traditional coronation seat of the kings of Scotland and, although the stone had been stolen by the English and spirited away to London, holding the coronation at the Abbey sent a message of defiance to the English king, Edward I.

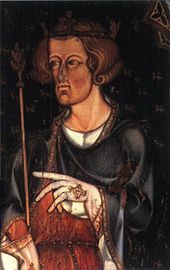

On 25 March 1306 Mary, Christian, Elizabeth and little Marjorie were all present when Robert the Bruce was crowned King Robert I by Isabella MacDuff, Countess of Buchan, who claimed her family’s hereditary right to crown Scotland’s kings (despite her being married to a Comyn). The ceremony was repeated on 27 March, following the late arrival of William Lamberton, Bishop of St Andrews. Robert’s coronation was the start of the most desperate period of his life – and that of his supporters. Edward I of England was never one to acquiesce when his will was flouted; he sent his army into Scotland to hunt down the new king and his adherents. After Robert’s defeat by the English at Methven in 1306, he went into hiding in the Highlands.

Robert sent his wife and daughter north to what he hoped would be safety. Mary, her sister Christan and Isabella, Countess of Buchan accompanied them, escorted by the Earl of Atholl and Mary and Christian’s brother, Sir Neil Bruce. It is thought that the Bruce women were heading north to Orkney to take a boat to Norway, where Robert’s sister, Isabel, widow of King Erik II, was still living. Unfortunately, they would never make it. The English caught up with them at Kildrummy Castle and laid siege to it. The defenders were betrayed by someone in their garrison, a blacksmith who set fire to the barns, making the castle indefensible.

The women managed to escape with the Earl of Atholl, but Neil Bruce remained with the garrison to mount a desperate defence, to give the queen, his niece and sisters enough time to escape. Following their capitulation, the entire garrison was executed. Sir Neil Bruce was subjected to a traitor’s death; he was hung, drawn and quartered at Berwick in September 1306 (not in front of the women he had protected, as portrayed in the film). Mary and her companions did not escape for long; they made for Tain, in Easter Ross, probably in the hope of finding a boat to take them onwards. They were hiding in the sanctuary of St Duthac when they were captured by the Earl of Ross (a former adherent of the deposed king John Balliol), who handed them over to the English. They were sent south, to Edward I at Lanercost Priory in Cumbria.

Edward I’s admirer, Sir Maurice Powicke, said Edward treated his captives with a ‘peculiar ferocity’.¹ Mary was treated particularly harshly by Edward I. The English king had a special cage built for her, although within the castle and not, as previously believed, hung from the walls of the keep at Roxburgh Castle, exposed to the elements and the derision of the English garrison and populace. In contrast, her sister Christian was sent into captivity to a Gilbertine convent at Sixhills, an isolated location, deep in the Lincolnshire Wolds. Christian languished at Sixhills for eight years, until shortly after her brother’s remarkable victory over the English at Bannockburn, in 1314. Despite Edward II escaping the carnage, King Robert the Bruce had managed to capture several notable English prisoners, including Humphrey de Bohun, 4th Earl of Hereford and Essex. Suddenly in a strong bargaining position, the Scots king was able to exchange his English captives for his family, held prisoners in England for the last 8 years.

Isabella MacDuff, Countess of Buchan, also suffered the harshly under Edward I’s not inconsiderable wrath. Isabella was probably born around 1270; she was the daughter of Colban, Earl of Fife, and his wife, Anna. Isabella was married to John Comyn, Earl of Buchan, and was first mentioned in 1297, when she was in England, managing her husband’s estates while he was in Scotland. Captured after the Scottish defeat at Dunbar in 1296, the Earl of Buchan had been sent north by Edward I, ordered to take action against Andrew Murray; however, he only took cursory action against the loyal Scot and soon changed sides, possibly fighting for the Scots at Falkirk in 1298. The Comyn family were cousins of Scotland’s former king, John Balliol, and constantly fought for his return to the throne, putting them in direct opposition to Robert the Bruce.

Isabella’s story remained unremarkable throughout Scotland’s struggles in the early years of the 1300s; until Robert the Bruce made his move for the throne in 1306. By birth, Isabella was a MacDuff, her father had been Earl of Fife and, in 1306, the current earl was her nephew, Duncan, a teenager who was a loyal devotee of Edward I. The Earls of Fife had, for centuries, claimed the hereditary right to crown Scotland’s kings. Although Duncan had no interest in being involved in the coronation of Robert the Bruce, Isabella was determined to fulfil her family’s role. It cannot have been an easy decision for her. Isabella’s participation was an act of bravery and defiance. She went against not only Edward I but her own husband, the Earl of Buchan. Isabella’s husband and the murdered John Comyn, Lord of Badenoch, were not only cousins but had a close relationship. It seems likely that Isabella’s husband was in England at the time of Bruce’s coronation, and she did not have to face him personally; but she would have known that her actions would mean there was no going back. Supporting Robert the Bruce, the man who stood accused of John Comyn’s murder, meant she turned against her husband and his entire family, people she had lived among for her entire married life.

Isabella reached Scone by 25 March 1306, in time to claim her family’s hereditary right to crown the new king, with Isabella placing the crown on the new Robert’s head. There are some rumours of a more intimate relationship between Isabella and Bruce, but these seem to be without foundation and are only to be expected, given that Isabel acted so decisively – and publicly – against her husband.

There was no going back for Isabella – crowning Robert the Bruce meant she was on her own; she couldn’t go back to her family, so she stayed with the royal party, travelling with Elizabeth de Burgh, the new queen, when Bruce sent her, his daughter and sisters, north for their safety. Isabella was with them when they escaped Kildrummy Castle by the skin of their teeth, and when they reached the shrine of St Duthac at Tain and were captured by William, Earl of Ross, in September 1306. As the party were sent south, Isabella must have faced the future with trepidation. Her placing the crown on Robert the Bruce’s head was the clearest challenge to Edward I and guaranteed that she would receive no sympathy from England’s king.

Even knowing that she would receive harsh treatment, it is doubtful that she, or indeed anyone, could have foreseen the punishment that Edward I would mete out. He ordered the construction of wooden cages, for Isabella and Bruce’s sister Mary; the two women were to be imprisoned in these cages close to the Scottish border, Isabella at Berwick Castle and Mary at Roxburgh Castle. Tradition has these cages were suspended from the walls of the castles’ keeps, open to the elements and the harsh Borders weather, the only shelter and privacy being afforded by a small privy. According to the Flores Historiarum, written at the Abbey of St Albans, Edward I said of Isabel’s punishment:

“[o]ne who doesn’t strike with the sword shall not perish by the sword. But because of that illicit coronation which she made, in a little enclosure made of iron and stone in the form of a crown, solidly constructed, let her be suspended at Berwick under the open heavens, so as to provide, in life and after death, a spectacle for passers-by and eternal shame.”²

It is doubtful, however, that the St Albans annalist was present when the order was given. The original royal writ still survives, written in French and reads a little differently;

“It is decreed and ordered by letters under the privy seal sent to the Chamberlain of Scotland, or his Lieutenant at Berwick-upon-Tweed, that, in one of the turrets within the castle at the same place, in the position which he sees to be most suitable for the purpose, he cause to be made a cage of stout lattice work of timber, barred and strengthened with iron, in which he is to put the Countess of Buchan.”³

This type of cage, within a room in the keep, was also used by Edward I to hold Owain, the son of Dafydd ap Gruffudd; he had been held at Bristol Castle since 1283 and had been secured in a cage, overnight, since 1305. The construction of the cages was intended to humiliate their occupants and, at the same time, Scotland’s new king. They were also a taunt; placing Isabella and Mary in these cages, in castles on the border with Scotland, it is possible they were intended as a challenge to Robert the Bruce, showing him that he was not powerful enough to protect his women, but also teasing him, hoping he would be drawn into a rescue attempt that would, almost certainly, lead to the destruction of his limited forces.

Despite Edward I’s death in 1307, Isabella, Countess of Buchan was held in her little cage in Berwick Castle for four years in total. Attempts to secure her release were made by Sir Robert Keith and Sir John Mowbray, by appealing to Duncan, Earl of Fife, but the appeals came to nought. It was only in 1310 that Mary and Isabella were released from their cages; Isabella was moved to the more comfortable surroundings of the Carmelite friary at Berwick. In 1313 she was put into the custody of Sir Henry de Beaumont, who was married to Alice, niece and co-heir of Isabella’s husband, John Comyn, Earl of Buchan. This is the last we hear of Isabella, Countess of Buchan, as she slips from the pages of history. It seems likely that Isabella died within the next year, probably due to her health being destroyed by the years of deprivation; she was not among the hostages who were returned to Scotland following the Scots’ victory at Bannockburn.

Mary, on the other hand, survived her ordeal and was returned to Scotland with the prisoner exchange that followed her brother’s victory at Bannockburn. She would be married twice after her release. Mary’s first husband was Sir Neil Campbell, a staunch supporter of her brother; the marriage being Neil’s reward for a lifetime of service to his king. The couple was to have one son, Iain (also John), and received the confiscated lands of David Strathbogie from the king; lands which passed to Iain on Neil’s death in 1316. In 1320 Iain was created Earl of Atholl as a consequence of his possession of the Strathbogie lands, and despite the rival claims of Strathbogie’s son. After Neil’s death Mary married a second time, to Alexander Fraser of Touchfraser and Cowie, by whom she had 2 sons, John of Touchfraser and William of Cowie and Durris.

Mary died in 1323, she had survived four years imprisoned in a cage at Roxburgh Castle before being transferred to a more comfortable imprisonment in 1310. It wouldn’t be surprising if this inhumane incarceration had contributed to Mary’s death in her early forties, as it had shortened the life of poor Countess Isabella.

The strength and bravery of these two women should never be underestimated, nor ignored. To survive 4 years imprisoned in a cage within a castle is remarkable. Even though they were not exposed to the elements, their movements, ability to exercise and exposure to fresh air were severely limited. Their courage and tenacity deserves to be remembered and celebrated. Their story deserves to be told.

*

Footnotes: ¹Marc Morris, A Great and Terrible King: Edward I and the Forging of Britain; ²Interim annalist, Flores Historiarum, Volume III; ³Pilling, David, Ladies in Cages (article)

Pictures courtesy of Wikipedia

*

Sources: The Story of Scotland by Nigel Tranter; Brewer’s British Royalty by David Williamson; Ladies in Cages (article) by David Pilling; Kings & Queens of Britain by Joyce Marlow; educationscotland.gov.uk/scotlandhistory Mammoth Book of British Kings & Queens by Mike Ashley; Oxford Companion to British History Edited by John Cannon; Edward I A Great and Terrible King by Marc Morris; Britain’s Royal Families by Alison Weir; A Great and Terrible King: Edward I and the Forging of Britain by Marc Morris; Buchan, Isabel, Countess of Buchan (b. c.1270, d. after 1313) by Fiona Watson, oxforddnb.com; thefreelancehistorywriter.com; englishmonarchs.co.uk.

*

My Books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online store.

Out now: King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye

In a time when men fought and women stayed home, Nicholaa de la Haye held Lincoln Castle against all-comers, gaining prominence in the First Baron’s War, the civil war that followed the sealing of Magna Carta in 1215. A truly remarkable lady, Nicholaa was the first woman to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Her strength and tenacity saved England at one of the lowest points in its history. Nicholaa de la Haye is one woman in English history whose story needs to be told…

King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is now available from Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

Coming 15 January 2024: Women of the Anarchy

On the one side is Empress Matilda, or Maud. The sole surviving legitimate child of Henry I, she is fighting for her birthright and that of her children. On the other side is her cousin, Queen Matilda, supporting her husband, King Stephen, and fighting to see her own son inherit the English crown. Both women are granddaughters of St Margaret, Queen of Scotland and descendants of Alfred the Great of Wessex. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how these women, unable to wield a sword, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It show how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other.

Available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK.

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, of the successes and failures of one of the most powerful families in England, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Defenders of the Norman Crown: Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey is now available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org.

Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org.

Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org.

Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell, and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online store.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

*

©2018 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS