Sometimes the similarities in the stories of medieval women are intriguing. Especially among families. Katherine Swynford’s story is one of the endurance of love and is unique in that she eventually married her prince. Katherine’s granddaughter, Joan Beaufort, is one half of, arguably, the greatest love story of the middle ages. I say arguably, of course, because many would say that Katherine’s was the greatest.

You may not consider a mistress as a heroine, seeing her as ‘the other woman’ and not worthy of consideration. However, women in the medieval era had little control over their own lives; if a lord wanted them, who were they to refuse? And even if they were in love, differences in social position could mean marriage was impossible – at least for a time.

Katherine was born around 1350; she was the younger daughter of Sir Payn Roelt, a Hainault knight in the service of Edward III’s queen, Philippa of Hainault, who eventually rose to be Guyenne King of Arms. Her mother’s identity is unknown, but Katherine and her older sister, Philippa, appear to have been spent their early years in Queen Philippa’s household. By 1365 Katherine was serving Blanche, Duchess of Lancaster, the first wife of John of Gaunt and Katherine was married to Sir Hugh Swynford of Coleby and Kettlethorpe, Lincolnshire, shortly after. The couple had three children, Thomas, Margaret, who became a nun, and Blanche, who was named after the duchess. John of Gaunt stood as little Blanche’s godfather and she was raised alongside his own daughters by Duchess Blanche.

Following Blanche’s death in 1368, Katherine was appointed governess to the duchess’s daughters. In September 1371 John of Gaunt was remarried, to Constance of Castile; Constance had a claim to the throne of Castile and John was soon being addressed as King of Castile. In the same year, Katherine’s husband, Sir Hugh Swynford, died whilst serving overseas and it seems that within months of his death, probably in the winter of 1371/72 Katherine became John’s mistress. Their first child, John Beaufort, was born towards the end of 1372. Over the next few years, three further children – two sons and a daughter – followed. John’s wife Constance also had children during this time – she gave birth to a daughter, Catherine, (Catalina) in 1373 and a short-lived son, John, in 1374.

We can only guess at what the two women thought of each other, but it can’t have been an easy time for either. In 1381, following the unrest of the Peasants’ Revolt and the hefty criticism aimed particularly at John and his relationship with Katherine, John renounced Katherine. Giving up her position as governess, Katherine left court and returned to Lincoln. Her relationship with John of Gaunt and, indeed, his family, remained cordial and the duke still visited her, although discreetly. In 1388 Katherine was made a Lady of the Garter – a high honour indeed. And in 1394 Constance died.

In January 1396, John and Katherine were finally married in Lincoln Cathedral; they had to obtain a dispensation from the church as John was godfather to Katherine’s daughter. With the marriage, Katherine had gone from being a vilified mistress to Duchess of Lancaster. Her children by John were legitimised by the pope in September 1396 and by Richard II’s royal patent in the following February, although they were later excluded from the succession by Henry IV.

Sadly, Katherine’s marital happiness with John of Gaunt was short-lived; John of Gaunt died in February 1399 and Katherine retired to live in Lincoln, close to the cathedral of which her second son by John, Henry, was bishop. Katherine herself died at Lincoln on 10 May 1403 and was buried in the cathedral in which she had married her prince. Her tomb can still be seen today and lies close to the high altar, beside that of her youngest child Joan Beaufort, countess of Westmorland, who died in 1440.

Although it seems easy to criticise Katherine’s position as ‘the other woman’, her life cannot have been an easy one. The insecurity and uncertainty of her position, due to the lack of a wedding ring, must have caused her much unease. However, that she eventually married her prince, where so many other medieval mistresses simply fell by the wayside and were forgotten, makes her story unique. What makes her even more unique is that Katherine’s own granddaughter was part of one of the greatest love stories of the middle ages.

Joan Beaufort was the only daughter of Katherine’s eldest son by John of Gaunt, also named John. The story of King James I of Scotland and his queen, Joan Beaufort, is probably the greatest love story of the medieval era. He was a king in captivity and she a beautiful young lady of the court of her Lancastrian cousin, Henry V. The son of Robert III of Scotland, James had been on his way to France, sent there for safety and to continue his education, when his ship was captured by pirates in April 1406. Aged only eleven, he had been handed over to the English king, Henry IV, and imprisoned in the Tower of London. Within a couple of months of his capture, James’s father had died, and he was proclaimed King of Scots, but the English would not release their valuable prisoner. James was closely guarded and regularly moved around, but he was also well-educated while in the custody of the English king and became an accomplished musician and poet.

Probably born in the early 1400s, Lady Joan was the daughter of John Beaufort, 1st Earl of Somerset. She was at court by the early 1420s, when James first set eyes on her. The Scottish king wrote of his love for Joan in his famous poem, The Kingis Quair. According to Nigel Tranter, James was with the court at Windsor, when he saw Joan for the first time; she was walking her little lapdog in the garden, below his window. The narrow window afforded him only a limited view, but the Lady Joan walked the same route every morning and James wrote of her;

Beauty, fair enough to make the world to dote,

Are ye a worldy creature?

Or heavenly thing in likeness of nature?

Or are ye Cupid’s own priestess, come here,

To loose me out of bonds

One morning James is said to have dropped a plucked rose down to Lady Joan, which he saw her wearing the following evening at dinner. Nigel Tranter suggests Lady Joan grieved over James’s imprisonment and even pleaded for his release. Written in the winter of 1423/24, the autobiographical poem, The Kingis Quair, gives expression to James’ feelings for Joan;

I declare the kind of my loving

Truly and good, without variance

I love that flower above all other things

James’s imprisonment lasted for eighteen years. His uncle Robert Stewart, Duke of Albany and Guardian of Scotland in James’s absence, refused to ransom him, in the hope of gaining the throne himself. He never quite garnered enough support, but managed to keep the Scottish nobles in check. However, when he died in 1420, control passed to his son Murdoch, and Scotland fell into a state of virtual anarchy. With Henry V’s death in 1422, it fell to his brother John, Duke of Bedford, as regent for the infant Henry VI, to arrange James’ release. The Scots king was charged 60,000 marks in ransom – ironically, it was claimed that it was to cover the costs for his upkeep and education for eighteen years. The agreement included a promise for the Scots to keep out of England’s wars with France, and for James to marry an English noble woman – not an onerous clause, given his love for Lady Joan Beaufort.

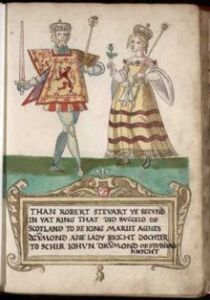

James and Joan were married at the Church of St Mary Overie in Southwark (now Southwark Cathedral) on 2 February 1424, with the wedding feast taking place in the adjoining hall, the official residence of Joan’s uncle Henry Beaufort, Bishop of Winchester. Finally united – and free – the young couple made their way north soon afterwards and were crowned together at Scone Abbey on 21 May 1424. James and Joan had eight children, seven of whom survived childhood. Their six daughters helped to strengthen alliances across Europe. The royal couple finally had twin sons on 16 October 1430; and although Alexander died within a year of his birth, his younger twin, James, thrived and was created Duke of Rothesay and heir to the throne. He would eventually succeed his father as James II.

On his return to Scotland, James immediately set about getting his revenge on the Duke of Albany’s family and adherents; executing some, including Murdoch, Albany’s son and heir. Two other claimants to James’s throne were sent to England, as hostages for the payment of his ransom. James and Joan ruled Scotland for thirteen years; James even allowed Joan to take some part in the business of government. Although the Scots were wary of her being English, Queen Joan became a figurehead for patronage and pageantry. The English hope that Joan’s marriage to James would also steer the Scots away from their Auld Alliance with France, was short-lived, however, and the 1436 marriage of their eldest daughter, Margaret, to the French dauphin formed part of the renewal of the Auld Alliance.

James’ political reforms, combined with his desire for a firm but just government, made enemies of some nobles, including his own chamberlain Sir Robert Stewart, grandson of Walter, Earl of Atholl, who had been James’s heir until the birth of his sons. Sir Robert and his grandfather hatched a plot to kill the king and queen. In February 1437, the royal couple was staying at the Blackfriars in Perth when the king’s chamberlain dismissed the guard and the assassins were let into the priory. The king is said to have hidden in an underground vault as the plotters were heard approaching. There is a legend that the vault had originally been an underground passage, however, the king had ordered the far end to be sealed, when his tennis balls kept getting lost down there. Unfortunately, that also meant James had blocked off his own escape route. The assassins dragged the king from his hiding place and stabbed him to death; Joan herself was wounded in the scuffle.

And one of the greatest love affairs of the era ended in violence and death. The plotters, far from seizing control of the country, were arrested and executed as the Scottish nobles rallied around the new king, six-year-old James II. Joan’s life would continue to be filled with political intrigue, but her love story had been viciously cut short, without the happy ending her grandmother had achieved. Joan would marry again, to Sir James Stewart, the Black Knight of Lorne. They would go on to have 3 sons together before Joan died during a siege at Dunbar Castle on 15 July, 1445; although whether her death was caused by illness or the violence of the siege has not been determined. She was buried in the Carthusian priory in Perth alongside her first husband, King James I.

Katherine and Joan led very different lives, although the similarities are there if you look for them; they both lived their lives around the glittering court and married for love. Joan’s happy marriage only achieved because her grandmother finally got her prince; if Katherine had not married John of Gaunt, the Beauforts would have remained illegitimate and their future prospects seriously restricted by the taint of bastardy.

*

Images courtesy of Wikipedia.

Sources:

katherineswynfordsociety.org.uk; Red Roses: Blanche of Gaunt to Margaret Beaufort by Amy Licence; The Nevills of Middleham by K.L. Clark; The House of Beaufort: the Bastard Line that Captured the Crown by Nathen Amin; Brewer’s British Royalty by David Williamson; History Today Companion to British History Edited by Juliet Gardiner & Neil Wenborn; The mammoth Book of British kings & Queen by Mike Ashley; Britain’s Royal Families, the Complete Genealogy by Alison Weir; The Life and Times of Edward III by Paul Johnson; The Perfect King, the Life of Edward III by Ian Mortimer; The Reign of Edward III by WM Ormrod; Chronicles of the Age of Chivalry Edited by Elizabeth Hallam; Oxforddnb.com; womenshistory.about.com/od/medrenqueens/a/Katherine-Swynford.

An earlier version of this article first appeared on The Henry Tudor Society blog in November 2017.

*

My Books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available, please get in touch by completing the contact me form.

Out now: King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye

In a time when men fought and women stayed home, Nicholaa de la Haye held Lincoln Castle against all-comers, gaining prominence in the First Baron’s War, the civil war that followed the sealing of Magna Carta in 1215. A truly remarkable lady, Nicholaa was the first woman to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Her strength and tenacity saved England at one of the lowest points in its history. Nicholaa de la Haye is one woman in English history whose story needs to be told…

King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is now available from Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

Coming 15 January 2024: Women of the Anarchy

On the one side is Empress Matilda, or Maud. The sole surviving legitimate child of Henry I, she is fighting for her birthright and that of her children. On the other side is her cousin, Queen Matilda, supporting her husband, King Stephen, and fighting to see her own son inherit the English crown. Both women are granddaughters of St Margaret, Queen of Scotland and descendants of Alfred the Great of Wessex. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how these women, unable to wield a sword, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It show how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other.

Available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK.

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, of the successes and failures of one of the most powerful families in England, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Defenders of the Norman Crown: Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey is now available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org.

Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org.

Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org.

Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

*

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

©2021 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS