In the mid-12th century, England was riven by civil war as King Stephen and Empress Matilda fought for a crown that was rightfully hers. In 1141, the empress came close to realising her ambition: Stephen had been captured and she was proclaimed ‘Lady of the English’, but the crown itself eluded her. Stephen’s wife, Queen Matilda, had fought back, captured the empress’s illegitimate half-brother, Earl Robert of Gloucester and negotiated a prisoner swap.

By January 1142, everyone was back where they started, with Stephen on the throne and Empress Matilda still fighting to wrest it from his grasp. In the early months of the year, both sides spent time consolidating their resources and manoeuvring for position rather than forcing a confrontation.

Except, things were a little more desperate. Her stocks were severely depleted and only her staunchest supporters remained with her; worse still, Stephen was now free to act on his own behalf. With the defection of Henry of Blois, Bishop of Winchester, back to his brother’s side, the church was against her as well.

The empress needed reinforcements. Her husband, Geoffrey of Anjou, implied that he would help, but only if her brother, Earl Robert, would come to him and ask in person. The empress was against the idea and Earl Robert was reluctant to leave his sister, not that Stephen was free again. But the king was lying ill at Nottingham, with rumours circulating that he was close to death. Robert decided it would be safe enough to leave for Normandy, though not without reservations.

Empress Matilda moved to Oxford to await her brother’s return. Although Oxford was not the most secure residence. It may have strong, high walls, but it was close to enemy territory. It was close to London. Her presence there would mean that the empress could act quickly, were Stephen to die.

But then, the king unexpectedly recovered.

And went on the offensive, taking Wareham, held by Earl Robert’s eldest son, William of Gloucester. It was the castle guarding that would have been the earl’s landing place on his return from Normandy. Stephen then marched to Cirencester, the castle was abandoned by the garrison on his approach. He burned it to the ground before moving on to Bampton and Radcot, both garrisoned by the empress’s forces; one was taken by storm while the other surrendered.

By taking the nearby castles, Stephen was isolating the empress at Oxford, cutting off any possible aid. And it was only when this was done that Stephen turned his sights on the empress.

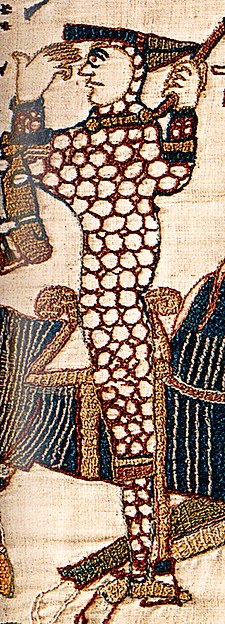

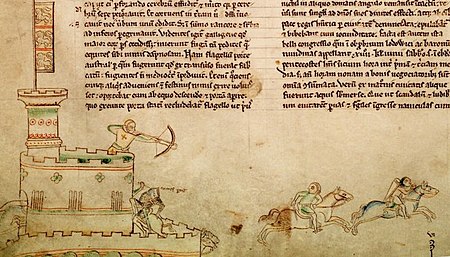

Oxford was a city protected by the surrounding Thames, guarded by a palisade on one side while the formidable castle, with its high donjon, stood sentinel on the other side. According to the Gesta Stephani, the king managed to find a deep ford by which he led his men across the river, ‘swimming rather than wading’, and launched an attack on the city’s defenders. When the defenders pulled back into the city, hoping to close the gates, the king’s forces mingled with them and made their way inside, burning buildings, killing those who resisted and capturing those who could offer a ransom. Others were ejected from the town, left to their own devices in the neighbouring countryside. While others were forced to seek shelter in the castle, with the empress.

The king encircled the castle, ordering that it be closely watched, day and night. The empress was not going to escape him again. There was slim chance of reinforcements coming to her aid. Her uncle David, King of Scots was back in Scotland, her loyal servant Miles of Gloucester, now Earl of Hereford, did not have enough men, and Brian FitzCount had to look to the defence of his own castle at Wallingford. And Earl Robert was still far away in Normandy, campaigning with Count Geoffrey while the latter made up his mind about sending reinforcements to aid his wife: over the summer and autumn of 1142, the two of them captured ten Norman castles.

On hearing of the empress’s predicament, Robert abandoned his quest for more troops and returned to England, forcing a landing at Wareham. With fifty-two ships and a force of between 300 and 400 knights in addition to foot soldiers, the earl managed to force Wareham’s surrender after a three-week siege. He then ordered a full muster of the empress’s forces at Cirencester before marching on Oxford to rescue his sister.

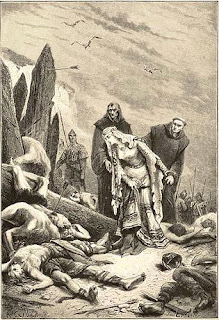

Shut up in the castle, with winter upon them, the empress and her forces were cold, hungry and desperate. Entirely cut off from the outside world, neither supplies nor news had been able to get past the king’s blockade since September. In the middle of December, with the ground white with snow and the river frozen, the empress made a desperate gamble.

‘Very hard pressed as she was and altogether hopeless that help would come she left the castle by night with three knights of ripe judgement to accompany her.’

Gesta Stephani

In the dark of the night, presumably dressed in white to camouflage against the blanket of snow, accompanied by just 3 men, she slipped out of a postern gate, and ‘in wondrous fashion she escaped unharmed through so many enemies, so many watchers in the silence of the night, whom the king had heedfully posted on every side of the castle.’ The empress walked 6 miles, crossing the frozen river and traversing the enemy’s pickets, to reach Wallingford Castle. The Gesta Stephani remarked that never had he ‘read of another woman so luckily rescued from so many mortal foes and from the threat of dangers so great’.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells the story slightly differently, saying that ‘in the night she was let down from the tower with ropes and stole out, and she fled and went on foot to Wallingford’.

Henry of Huntingdon added the detail that the empress was dressed in white, as camouflage: ‘Not long before Christmas, the empress fled across the frozen Thames, clothed in white garments, which reflected and resembled the snow, deceiving the eyes of the besiegers.’

Though they all tell the story slightly differently, every chronicler eagerly tells of the empress’s daring escape from Oxford Castle.

With the empress safely ensconced at Wallingford with Brian FitzCount, the garrison at Oxford could surrender. The king, deprived of his quarry, agreed easy terms with the remaining defenders.

Earl Robert, on hearing of his sister’s escape, stopped his advance on Oxford and instead made for Devizes, where brother and sister were reunited. The earl had brought a surprise for his sister. After 3 years apart, she was reunited with her eldest son, Henry of Anjou. Henry’s presence served to show England that Henry I’s heir was Empress Matilda’s nine-year-old son, Henry, rather than Stephen’s twelve-year-old son, Eustace.

Henry was placed in the household of his uncle, Earl Robert, and sent to Bristol to continue his education, alongside his cousin Roger, the earl’s younger son, who would later become Bishop of Worcester. Henry remained at Bristol until March 1144 and soon began to receive homage from his English vassals in person.

The war changed shaped at this time, with empress and earl consolidating their position in their own lands but biding their time, waiting for Henry to grow old enough to take over the reins of the struggle.

Henry’s presence changed the focus of Matilda’s campaign. She now realised that she would never sit on her father’s throne. But there was a new generation to fight for. The empress’s purpose was now to secure the throne for Henry in the next reign rather than to displace Stephen in this one.

*

An earlier version of this article appeared in the 4th edition of Living Medieval Magazine.

Sources:

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, edited and translated by Michael Swanton; Gesta Stephani, translated by K. R. Potter; Henry of Huntingdon, The History of the English People 1000-1154, translated by Diana Greenway; Henry of Huntingdon, The Chronicle of Henry of Huntingdon; Ordericus Vitalis, The Ecclesiastical History of England and Normandy; Matthew Lewis, Stephen and Matilda’s Civil War: Cousins of Anarchy; Catherine Hanely, Matilda: Empress, Queen, Warrior; Edmund King, King Stephen.

Images:

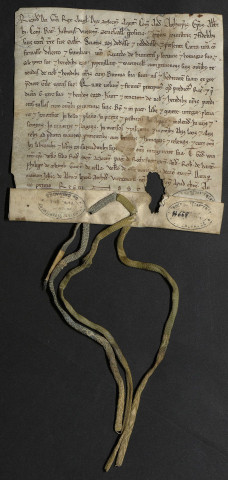

Courtesy of Wikipedia, except Oxford Castle which is used with the kind permission of Jayne Smith

*

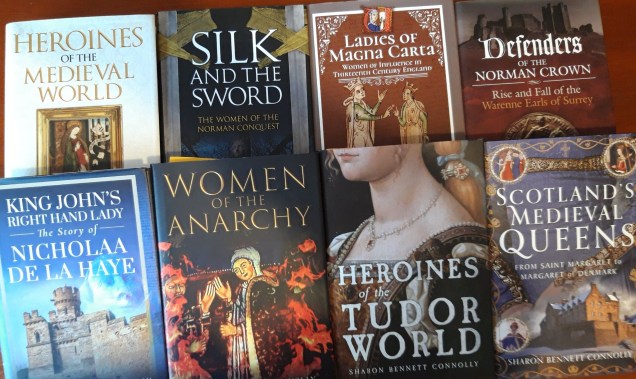

My Books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

Out now: Scotland’s Medieval Queens

Scotland’s history is dramatic, violent and bloody. Being England’s northern neighbour has never been easy. Scotland’s queens have had to deal with war, murder, imprisonment, political rivalries and open betrayal. They have loved and lost, raised kings and queens, ruled and died for Scotland. From St Margaret, who became one of the patron saints of Scotland, to Elizabeth de Burgh and the dramatic story of the Scottish Wars of Independence, to the love story and tragedy of Joan Beaufort, to Margaret of Denmark and the dawn of the Renaissance, Scotland’s Medieval Queens have seen it all. This is the story of Scotland through their eyes.

‘Scotland’s Medieval Queens gives a thorough grounding in the history of the women who ruled Scotland at the side of its kings, often in the shadows, but just as interesting in their lives beyond the spotlight. It’s not a subject that has been widely covered, and Sharon is a pioneer in bringing that information into accessible history.’ Elizabeth Chadwick (New York Times bestselling author)

Available now from Amazon and Pen and Sword Books

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. Heroines of the Tudor World is now available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how Empress Matilda and Matilda of Boulogne, unable to wield a sword themselves, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It shows how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other. Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org. Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell and Elizabeth Chadwick, and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved. Our first ever episode was on The Anarchy!

Every episode is also now available on YouTube.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter, Threads, Bluesky and Instagram.

Article: 2024 © Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS