When writing non-fiction biographies, you can tell the life of a person. You can say what happened to them, how they affected events and how they were perceived by others. But there are gaps. If you do not have the evidence, you cannot just make it up. If you are looking for reasons, you can offer different scenarios. It is hard to get to the heart of a person, though. You cannot put words in their mouths, or attribute feelings and emotions. Fiction can go where non fiction cannot tread. It can give you a vivid retelling of a fabulous story. It is not always historically accurate, there are some things we cannot know, but fiction can fill in the gaps. It can bring the past to life and give you a sense of the era that no other medium can.

And that is what Terri Lewis has achieved with remarkable skill in her novel if Isabelle d’Angoulême, Behold the Bird in Flight. And it is a pleasure to welcome Terri to History…the Interesting Bits to talk a little about her research behind her novel.

Finding Isabelle, a Mother and a Queen

by Terri Lewis

I was in high school when I first asked my history teacher, “Where are the women?” An unsatisfactory answer gave impetus to what became a need to find forgotten women. Eventually I became obsessed with Isabelle d’Angoulême, King John’s second wife, and decided to resurrect her by writing a novel.

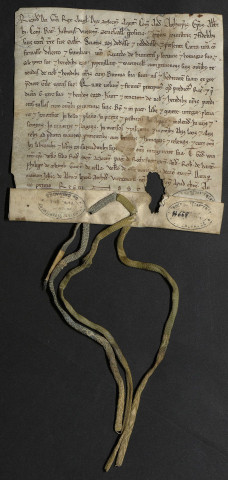

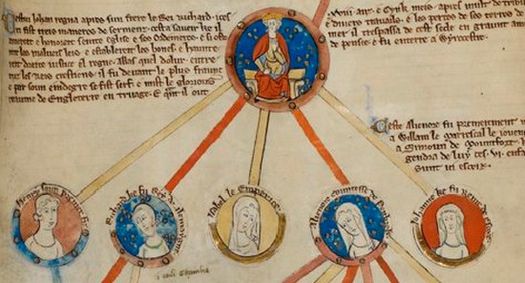

There are a few documented facts about her life: Historians think she was about twelve years old when John abducted her from her French fiancé, took her to England, and crowned her queen. The chronicles, when they bothered to mention her, were not kind; Matthew Paris called her a “Jezebel” and “slut” who kept John in bed until noon, an assessment most likely reflecting John’s reputation, not the reality of his wife. Isabelle apparently didn’t receive the normal queen’s gold—a percentage of John’s income—or the rents from lands given to her at the time of their marriage; John kept the monies for himself. In “history,” I found only men – fighting, amassing money and enemies, riding off to conquer unknown lands, signing writs, allowing fairs, courting and dancing and always fighting. Isabelle’s life, like the lives of most medieval women, was mainly blank.

But. . . she bore John five children.

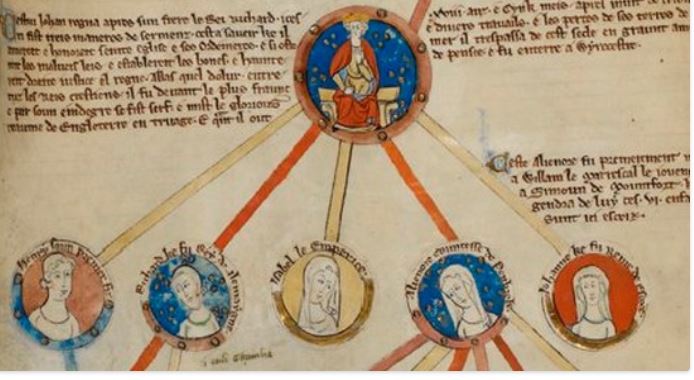

My research on medieval childbirth uncovered dire statistics: 20% to 33% of medieval women died from childbearing. The mortality rate per single birth was only slightly higher than in modern times, but multiple pregnancies compounded the risk. Birth control was forbidden by the all-powerful Church so basically a fertile woman had children until menopause or until she died. Because kings had to have sons, as did counts and dukes and other lords—a child to inherit land and carry on the family name. Daughters were less important. An only-child daughter could inherit a kingdom , but not for herself, for her husband. Girls who had brothers would serve as bargaining chips in marriages that formed diplomatic alliances or enlarged territory for their fathers.

In another statistic, infants were uncertain to live to inheritance. Nicholas Orme wrote, “It has been suggested that 25% of [medieval children] may have died in their first year, half as many (12.5%) between one and four, and a quarter as many (6%) between five and nine.” Danger was everywhere. A cut could become infected and penicillin was years in the future. Children fell into wells and down stone stairs, or into the fire that burned in the middle of the great hall, the main source of heat. Many died of illnesses for which bleeding or herbal concoctions were the only cure. Multiple pregnancies mitigated this danger. I note that Isabelle, in addition to the five children with John, had nine more children with her second husband. But two of her own daughters died in childbirth.

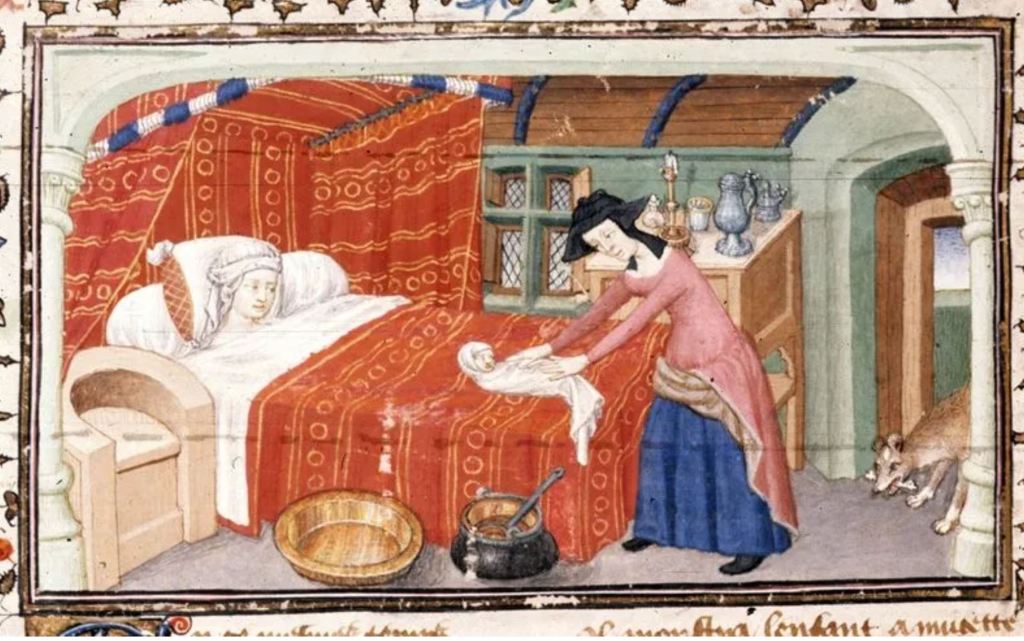

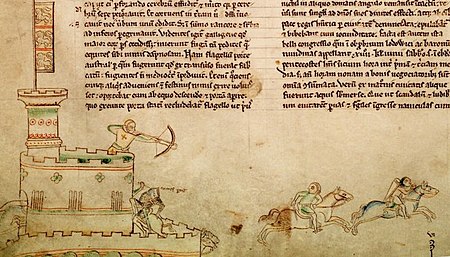

Isabelle wouldn’t have gone to a hospital. She’d have had a lying-in chamber removed from the main keep and furnished with a birthing stool, a midwife with practical experience but not a doctor because childbirth was a woman’s domain and doctors were men, and a room full of ladies-in-waiting who watched and prayed with her. If the birth was difficult, window shutters would be opened to release the new soul into life. If that failed, an arrow could be shot heavenward to waken God to the peril and ask for his help.

Since history decreed that Isabelle would live through childbirth, I decided to have her observe the suffering of her best friend. That scene became an important milestone in Isabelle’s growing up.

What kind of mother would Isabelle have been? I’d never read about a medieval mother. Women in 1200 who appeared in the chronicles were queens, royalty, or religious. Motherhood was important only for the child, preferable a boy, a gift to the father. The woman was just a bearing body.

I decided that Isabelle learned from her own mother, Alice de Courtney, the granddaughter of Louis le Gros of France. Alice would have been familiar with expectations for noble daughters. And she was married three times. I tried to imagine the experience of being handed to various husbands like a package—the decisions being made by fathers and kings. Perhaps she had grounded herself in her new household with a new husband by following the rules. The first “courtesy book” setting forth standards of behavior— Liber Urbani or the book of civilized man— appeared in England late in the 12th century. Written in Latin, the long poem contained general advice such as honor your parents, hold your tongue, don’t mount your horse in the great hall, and such gems as “when you pick up food with a spoon, do not shovel it on board with your thumb.”

I needed to imagine a relationship between Isabelle and her mother. When I was twelve, my mother was the center of everything; I’d come home from school and stand in the kitchen to tell stories about my friends or things the teacher said. But Isi’s mother wouldn’t be in the kitchen. She was a countess; she’d have cooks and laundresses and maids. I couldn’t imagine that she was anything to Isabelle but a rule-maker. And Isabelle’s position required rules. When she was of age, she would be married – handed off in essence – to another count. The marriage would presumably involve a castle and her husband would go off to war or crusade or to visit a king, and Isabelle would be required to manage the vast operation of the castle while he was gone. Even when he was home, she would oversee household tasks, her belt laden with keys to various chests of fabric or spices, to rooms holding barrels of wine and other supplies. So I made her mother strict, set Isabelle chafing against her, then allowed her to escape, grow up a bit, marry John, and have her children.

Two boys first. Then three girls. Today one can find numerous mothers writing how overpowering love when their baby was laid on their breast changed their lives. But as queen of an itinerant court, Isabelle lived on the road with John who visited barons, trying to bring them to heel. So breastfeeding was impractical. It also acted as a form of contraception and Isabelle’s job was to conceive as often as possible and give John heirs. This meant that her babies would be handed over at birth to a wet-nurse, a hired woman who’d breast feed them as if her own. So the first attachment of mother to child was cut off and understandably, wet nurses often developed close relationships with their charges, particularly as children were generally breastfed for longer than they are today – boys often up to the age of two.

At age seven, the boys would have sent to other noble castles for education. Perhaps the idea was that those other educators would have less attachment to the children and thus they would supply a strict upbringing without coddling. Isabelle’s girls would have remained with her as the kingdom fell deeper into chaos. The Barons were revolting, the Pope had excommunicated John, the French were threatening to invade and conquer. With a growing sense that the throne would be gone before her ten-year-old son Henry could assume it, Isabelle would have known the French would kill him along with the rest of her children, leaving no pretenders. How best to save them? I’ll leave that inside the novel and just say she managed as best she could. History has condemned her ultimate decision, but I understand how she came to it.

About the book:

Romantic and stubborn, eleven-year-old Isi plans to marry for love and be mistress of her own castle. But life in 1198 is full of threat and a series of tragic events teaches her growing up is hard. When Isi falls for Hugh, a French nobleman, he consents to marry her, but only for her dowry. She longs for more. Hoping a jealous man will fall in love, she flirts with a king. The flirtation backfires: King John abducts and marries her. Now trapped in cold, warring England with a malicious husband, Isi must hide her yearning for Hugh and find her own power. If she fails, she won’t live to return to her beloved. Inspired by real historical figures—Isabelle d’Angoulême, Hugh de Lusignan, and King John of Magna Carta fame—Behold the Bird in Flight is set in a period that valued women only for their dowries and childbearing. Isabelle’s story has been mainly erased by men, but the medieval chronicles suggest a woman who developed her own power and wielded it. And as the woman behind the throne, who’s to say she didn’t influence history?

About the Author:

Terri Lewis fell in love with medieval history in college. Not the dates or wars, but the mysterious daily lives of the people. Finally two sentences in a book bought at Windsor Castle led her to write her debut novel, Behold the Bird in Flight, A Novel of an Abducted Queen.

Published in Denver Quarterly, Blue Mesa Review, and Chicago Quarterly Review among others, and accepted to the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, she has worked with Laura van den Berg, Jill McCorkle, and Rebecca Makkai. Shortlisted for LitMag’s Virginia Woolf Award for Short Fiction, she won the 2025 Miami University Press Novella Prize. She reviews for The Washington Independent Review of Books.

Before she was an author, she had career as a ballet dancer in Denver and Germany, ran a dance company in Arkansas, earned a B.A. in history and education, and an M.A. in theater, not necessarily in that order. She lives with her husband and two lively dogs in Denver, Colorado.

Where to find Terri:

Website: Substack: Instagram: terri.lewis1: Facebook: terri lewis author

Buy the book at Amazon.com (in $), Amazon.co.uk (in £), and Amazon.Fr (in €)

*

My Books:

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

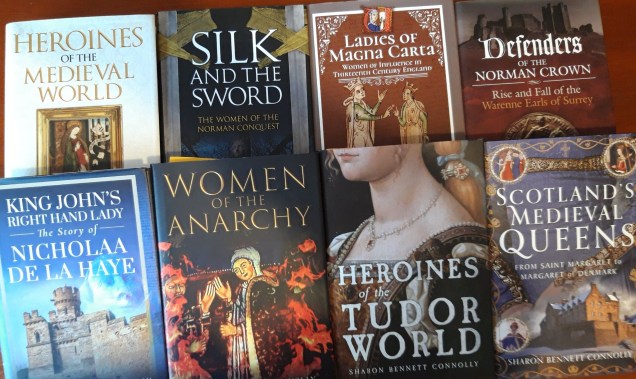

Out now: Scotland’s Medieval Queens

Scotland’s history is dramatic, violent and bloody. Being England’s northern neighbour has never been easy. Scotland’s queens have had to deal with war, murder, imprisonment, political rivalries and open betrayal. They have loved and lost, raised kings and queens, ruled and died for Scotland. From St Margaret, who became one of the patron saints of Scotland, to Elizabeth de Burgh and the dramatic story of the Scottish Wars of Independence, to the love story and tragedy of Joan Beaufort, to Margaret of Denmark and the dawn of the Renaissance, Scotland’s Medieval Queens have seen it all. This is the story of Scotland through their eyes.

‘Scotland’s Medieval Queens gives a thorough grounding in the history of the women who ruled Scotland at the side of its kings, often in the shadows, but just as interesting in their lives beyond the spotlight. It’s not a subject that has been widely covered, and Sharon is a pioneer in bringing that information into accessible history.’ Elizabeth Chadwick (New York Times bestselling author)

Available now from Amazon and Pen and Sword Books

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. Heroines of the Tudor World is now available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how Empress Matilda and Matilda of Boulogne, unable to wield a sword themselves, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It shows how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other. Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org. Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell and Elizabeth Chadwick, and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

Every episode is also now available on YouTube.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter, Threads, Bluesky and Instagram.

*

©2025 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS and Terri Lewis