It is impossible to talk about anything related to Magna Carta without mentioning the man who has come to be known as ‘the Greatest Knight’: William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke, and his family. Marshal was one of the few nobles to stay loyal to King John throughout the Magna Carta crisis. That is not to say that the king and Marshal did not have their differences, nor that their relationship was always smooth sailing. However, William Marshal was famed for his loyalty and integrity and maintained his oaths to King John throughout his reign, regardless of the distrust between the two men.

The children of William and his wife, Isabel de Clare, cannot fail to have benefited from William Marshal’s rise through the ranks from fourth son and humble hearth knight, to earl of Pembroke and, eventually, regent for King Henry III. Their father’s position as a powerful magnate on the Welsh Marches, and the most respected knight in the kingdom, saw William’s daughters make advantageous marriages in the highest echelons of the English nobility.

William and Isabel were the parents of 10 children who survived to adulthood, 5 boys and 5 girls. In a bizarre and sad twist of fate, each of the boys would, in turn, succeed to the earldom, with not one leaving a male heir to continue the Marshal line. Of the girls, the couple’s eldest daughter was Matilda, also known as Maud or Mahelt. Given that her parents married in 1189 and she had two elder brothers, Matilda was probably born in 1193 or 1194. The Histoire de Guillaume le Maréchal wrote glowingly of Matilda, saying she had the gifts of

‘wisdom, generosity, beauty, nobility of heart, graciousness, and I can tell you in truth, all the good qualities which a noble lady should possess.’

Histoire de Guillaume le Maréchal

The Histoire goes on to say;

‘Her worthy father who loved her dearly, married her off, during his lifetime to the best and most handsome party he knew, to Sir Hugh Bigot.’

Histoire de Guillaume le Maréchal

Unfortunately for Matilda, her husband Hugh, the eldest son of the earl of Norfolk, was among the rebels during the Magna Carta crisis; their eldest son was taken hostage by the king when their castle at Framlingham surrendered to the royal army. It must have been a comfort to Matilda that, on John’s death, her son’s welfare, while still a hostage, would have been supervised by the new regent, the boy’s grandfather. When Hugh died in 1225, Matilda married for a second time just a few months later, to William de Warenne, Earl of Warenne and Surrey, thus uniting the Bigod, Warenne and Marshal families. The marriage appears to have been one of convenience rather than love but produced 2 children, a boy and a girl, John and Isabel. Matilda’s son by her second marriage, John de Warenne, joined his 3 older Bigod half-brothers, Roger, Hugh and Ralph as pall bearers for their mother’s coffin at her funeral in 1248, when she was laid to rest beside her mother at Tintern Abbey in Monmouthshire.

The next daughter, Isabel, was at least six years younger than Matilda, born in 1200. She was married to Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester and Hertford, who was twenty years her senior. Gilbert was the son of Richard de Clare, earl of Hertford, and Amicia, coheiress of William, Earl of Gloucester; through his mother he could trace his ancestry back to King Henry I, albeit through king’s illegitimate eldest son, Robert of Gloucester, the stalwart supporter of his half-sister, Empress Matilda. Gilbert’s aunt, Amicia’s sister, was Isabella of Gloucester, the discarded first wife of King John, who had held the earldom of Gloucester until her death on 14 October 1217, when it passed to Gilbert.

Both Gilbert and his father were named among the twenty-five barons appointed as Enforcers of Magna Carta in 1215; as a consequence, father and son were excommunicated at the beginning of 1216. After the death of King John, Gilbert sided with Prince Louis of France and was only reconciled with the royalist cause after the Battle of Lincoln in May 1217. This was despite having married Isabel, the second daughter of William Marshal, in 1214; Marshal had been regent of England for 9-year-old Henry III since King John’s death in October 1216. Like her older sister, Isabel had found her husband’s family were on the opposing side to her father in the Magna Carta crisis and the civil war that followed. They had 6 children together before Gilbert’s death in October 1230; he died on the return journey from an expedition to Brittany. Isabel was married again, not 6 months later, to the king’s younger brother, Richard, Earl of Cornwall. The early deaths of at least 2 children put a strain on this marriage and Richard had been seeking a divorce when Isabel found herself pregnant again. She was safely delivered of the longed-for son and heir, Henry of Almain in 1235. Tragically, Isabel herself died in childbirth, in 1240. Her baby son, Nicholas, died the same day.

The next-youngest of the Marshal sisters, Sibyl, was born around 1201: she was married to William de Ferrers, fifth earl of Derby. Unlike her elder sisters, Sibyl and her husband played little part in national affairs. Ferrers had been plagued by gout since his youth and led a largely secluded life. He was regularly transported by litter. Further, he had never fully recovered from an accident that had happened sometime in the 1230s. While crossing a bridge at St Neots in Huntingdonshire, Ferrers was thrown from his litter, into the water. It must have been a terrifying experience. He succeeded to the earldom of Derby on his father’s death in 1247 but died in 1254. During the marriage Sibyl gave birth to 7 children, all daughters: Agnes, Isabel, Maud, Sibyl, Joan, Agatha and Eleanor. Sibyl died sometime before 1247 and was laid to rest at Tintern Abbey, alongside her mother.

William and Isabel Marshal’s fourth daughter, Eva, was born in about 1203 in Pembroke Castle, and so was only 16 when her father died – and 17 when she lost her mother. As a child, she spent several years with her family in exile in Ireland, only returning to England when her father was finally reconciled with King John in 1212. Sometime before 1221, Eva was married to William (V) de Braose, Lord of Abergavenny, son of Reginald de Braose and grandson of Matilda de Braose, who had died of starvation in King John’s dungeons in 1210. William de Braose was a wealthy Norman baron with estates along the Welsh Marches. He was hated by the Welsh, who had given him the nickname Gwilym Ddu, or Black William, and had been taken prisoner by Llywelyn ap Iorweth – Llywelyn the Great – in 1228.

Although he had been released after paying a ransom, de Braose later returned to Llywelyn’s court to arrange a marriage between his daughter, Isabella, and Llywelyn’s son and heir, Dafydd. During this stay, Eva’s husband was ‘caught in Llywelyn’s chamber with the King of England’s daughter, Llywelyn’s wife’. Whilst Llywelyn’s wife, Joan, Lady of Wales, the illegitimate daughter of King John, was imprisoned for a year, a much worse fate was meted out to William de Braose. He was publicly hanged on Llywelyn’s orders, leaving Eva a widow at the age of 27, with 4 young daughters, all under the age of 10. Despite the discomfort caused by Llywelyn’s execution of Braose, the marriage of Isabella and Dafydd went ahead, following some impressive diplomacy on Llywelyn’s part. Eva never remarried and spent her widowhood managing her own lands. She was caught up the revolt of her brother, Richard, in 1234, and appears to have acted as intermediary between her brother and the king to help resolve the situation. She died in 1246.

The youngest Marshal sister was Joan, who was still only a child when William Marshal died in 1219, being born in 1210. She is mentioned in the Histoire as having been called for by her ailing father, so that she could sing for him. Joan was married, before 1222, to Warin de Munchensi, a landholder and soldier who was born in the mid-1190s. When his father and older brother died in 1204 and 1208 (possibly), respectively, Warin was made a ward of his uncle William d’Aubigny, Earl of Arundel. He was ill-treated by King John, who demanded 2,000 marks in relief and quittance of his father’s Jewish debts on 23 December 1213. He was ordered to pay quickly and pledged his lands as a guarantee of his good behaviour.

This harsh treatment drove him to ally with the rebel barons and he was captured fighting against the royalist forces, and his father-in-law, at the Battle of Lincoln, on 20 May 1217. He was, soon after, reconciled with the crown and served Henry III loyally on almost every military campaign of the next forty years. His marriage to Joan Marshal produced two children; John de Munchensi and a daughter, Joan, who would marry the king’s half-brother, William de Valence, fourth son of Isabelle d’Angoulême and her second husband, Hugh X de Lusignan, Count of La Marche. It was through his wife and, more accurately her mother, that William de Valence was allowed to accede to the earldom of Pembroke following the extinction of the Marshal male line. Joan Marshal died in 1234 and so never saw her daughter marry and become countess of Pembroke in 1247.

The various experiences of the 5 Marshal daughters serve as a demonstration of the divisions among the nobility, caused by the Magna Carta crisis, with several of them finding themselves on the opposing side to that of their father. It must have been a source of great anxiety for a family which appears to have been otherwise very close. These 5 young women also provide a snapshot of the fates of women in thirteenth century England, death in childbirth, early widowhood and second marriages arranged for personal security rather than love. What is evident is that, just like their father, these girls were an integral part of the Magna Carta story.

*

An earlier version of this article first appeared on Samantha Wilcoxson’s blog.

Sources:

Rich Price, King John’s Letters Facebook group; Robert Bartlett England Under the Norman and Angevin Kings 1075-1225; Dan Jones The Plantagenets; the Kings who Made England; The Plantagenet Chronicle Edited by Elizabeth Hallam; Maurice Ashley The Life and Times of King John; Roy Strong The Story of Britain; Oxford Companion to British History; Mike Ashley British Kings & Queens; David Williamson Brewer’s British Royalty; Ralph of Diceto, Images of History; Marc Morris, King John; David Crouch, William Marshal; Crouch and Holden, History of William Marshal; Crouch, David, ‘William Marshal [called the Marshal], fourth earl of Pembroke (c. 1146–1219)’, Oxforddnb.com; Flanagan, M.T., ‘Isabel de Clare, suo jure countess of Pembroke (1171×6–1220)’, Oxforddnb.com; Thomas Asbridge, The Greatest Knight; Chadwick, Elizabeth, ‘Clothing the Bones: Finding Mahelt Marshal’, livingthehistoryelizabethchadwick.blogspot.com; Stacey, Robert C., ‘Roger Bigod, fourth earl of Norfolk (c. 1212-1270)’, Oxforddnb.com; finerollshenry3.org.uk; Vincent, Nicholas, ‘William de Warenne, fifth earl of Surrey [Earl Warenne] (d. 1240)’, Oxforddnb.com.

My Books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

Out now: Scotland’s Medieval Queens

Scotland’s history is dramatic, violent and bloody. Being England’s northern neighbour has never been easy. Scotland’s queens have had to deal with war, murder, imprisonment, political rivalries and open betrayal. They have loved and lost, raised kings and queens, ruled and died for Scotland. From St Margaret, who became one of the patron saints of Scotland, to Elizabeth de Burgh and the dramatic story of the Scottish Wars of Independence, to the love story and tragedy of Joan Beaufort, to Margaret of Denmark and the dawn of the Renaissance, Scotland’s Medieval Queens have seen it all. This is the story of Scotland through their eyes.

‘Scotland’s Medieval Queens gives a thorough grounding in the history of the women who ruled Scotland at the side of its kings, often in the shadows, but just as interesting in their lives beyond the spotlight. It’s not a subject that has been widely covered, and Sharon is a pioneer in bringing that information into accessible history.’ Elizabeth Chadwick (New York Times bestselling author)

Available now from Amazon and Pen and Sword Books

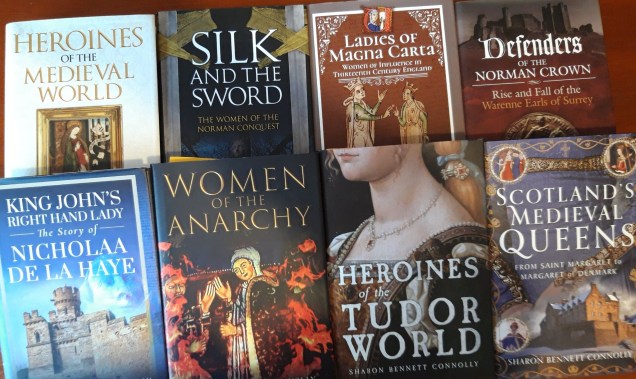

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. Heroines of the Tudor World is now available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how Empress Matilda and Matilda of Boulogne, unable to wield a sword themselves, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It shows how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other. Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

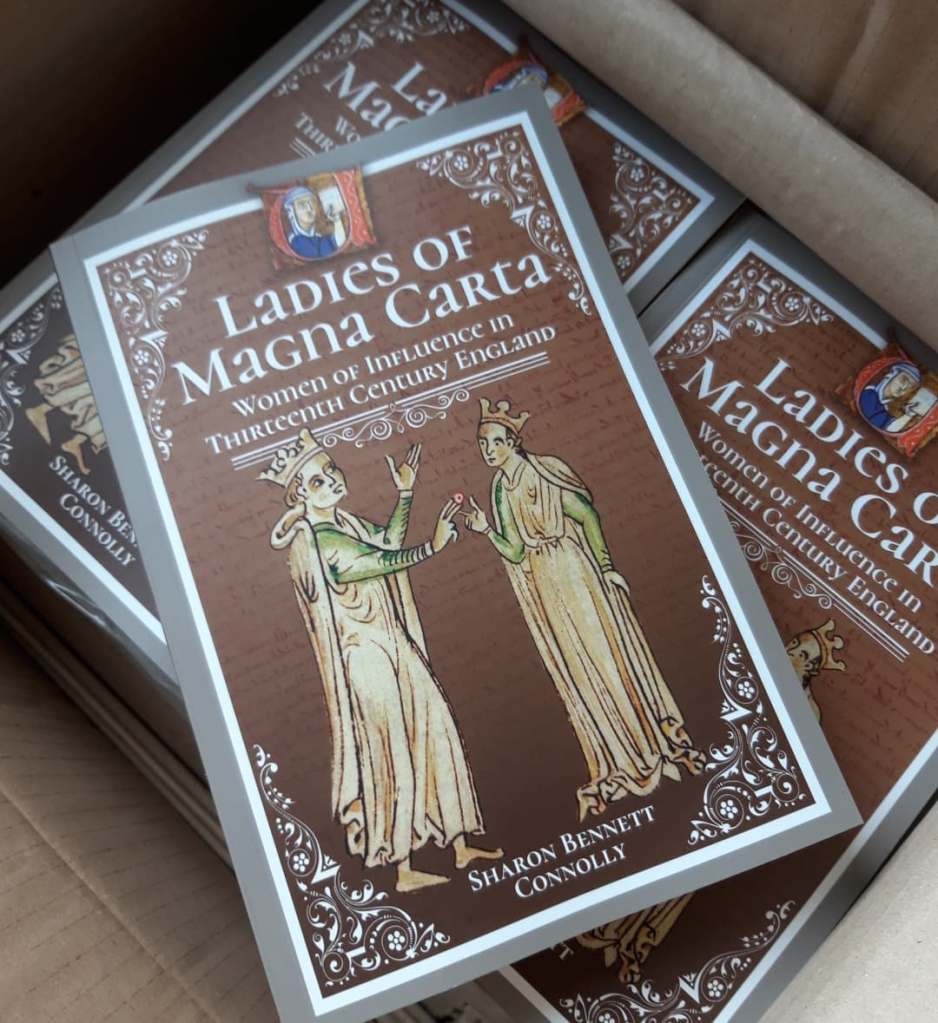

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org. Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell and Michael Jecks, and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved. Including an episode on William Marshal with Elizabeth Chadwick, author of The Greatest Knight. Every episode is now available on YouTube.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter, Threads, Bluesky and Instagram.

*

©2021 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS