Growing up near Conisbrough Castle, South Yorkshire, I did not know much about its history. It was rather underrated. We always thought it was just a bland old place – it was great for exploring and rolling down the hills and playing hide and seek in the inner bailey. However, being so far from London, the centre of power, it didn’t seem to have much history or national importance. The most famous thing about it was that it was used as the Saxon castle in Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe.

The castle’s early history

English Heritage have spent a lot of money on it in recent years. When I worked there in the early 1990s there was no roof, it was open to the elements, with green moss on the walls and erosion caused by acid rain. And there was just a very narrow walkway around the inside of the keep. It was just a shell. Now it has a roof, floors on every level, sensitive lighting, information videos on each floor and a fantastic little visitor centre with a small museum. It looks so much better (although I still wouldn’t want to stand on the battlements on a windy day like today).

When I joined the castle team as a volunteer tour guide, I started looking into the actual history of the Castle, seeing it more for what it has been, than for the visitor attraction it is now. Instead of being a forgotten, unimportant little castle in the middle of nowhere, Conisbrough Castle comes to life through the history it has been a part of, and the people who have called it home.

According to Geoffrey of Monmouth, in his Historia Regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain), Conisbrough was founded as ‘Conan’s Burg’ by a British leader called Conan. It was said to have later belonged to Ambrosius Aurelianus, a candidate for the legendary King Arthur. As Geoffrey of Monmouth says, Ambrosius captured the Saxon leader Hengist, once a mercenary for Vortigern, at the battle of ‘Maisbeli.’ And brought him to his stronghold at Conisbrough. Hengist was then beheaded on Ambrosius’ orders and buried at the entrance to the castle of ‘Cunengeburg’, that is Conisbrough. A small hill, locally called Hengist’s Mound, is in the grounds of the outer bailey.

What we know, for certain, is that by 1066 the Honour of Conisbrough belonged to Harold Godwinson, Earl of Wessex and later King Harold II of England, though there is no evidence that he ever visited. On a prominent, steep hill, the castle guards the main road between Sheffield and Doncaster to the east, and the navigable River Don to the north.

Following Harold’s defeat and death at the Battle of Hastings, and shortly after the Harrying of the North of 1068 Conisbrough was given to one of William the Conqueror’s greatest supporters, William de Warenne. Warenne was a cousin of Duke William of Normandy and fought alongside him at the Battle of Hastings. He was given land in various counties, including Lewes in Sussex and Conisbrough in Yorkshire; and although he developed his property at Castle Acre in Norfolk, little was done at Conisbrough. In those days the castle itself was little more than a wooden motte and bailey construction, surrounded by wooden palisades and earthworks.

*

A thoroughly modern Castle

It was not until the reign of Henry II that the Castle began to take on the majestic appearance we know today. Conisbrough came into the hands of Hamelin Plantagenet, illegitimate half-brother of King Henry II; Hamelin had married the de Warenne heiress, Isabel, 4th Countess of Warenne and Surrey, and became 4th Earl of Warenne and Surrey by right of his wife.

It was Hamelin who built the spectacular hexagonal keep that we can see today. The stairs to the keep were originally accessed across a drawbridge, which could be raised in times of attack. The ground floor was used for storage, with a basement storeroom below, housing the keep’s well, and accessed by ladder.

The first floor holds the great chamber, or solar, with a magnificent fireplace and seating in the glass-less window. According to Margaret Wood’s The English Medieval House, “It has been shown * that the two earliest known examples of a hooded fireplace, at Conisborough [sic] keep (c. 1185)‘ in Yorkshire (PI. XLI p), occur where the circular plan of the room made an arched fireplace difficult to construct. Here a lintel was formed along a chord of the circumference, and the resulting filling above assumed a hooded form.” This is where the Lord would have conducted business, or entertained important guests. Henry II, King John and King Edward II are known to have visited Conisbrough: King John even issued a charter from Conisbrough Castle in March 1201.

The second floor would have been sleeping quarters for the lord and lady. Both the solar and the bedchamber have impressive fireplaces, garderobes and a stone basin, which would have had running water delivered from a rainwater cistern on the roof.

On this floor, also, built into one of the keep’s buttresses is the family’s private chapel. This may well have been the chapel endowed by Hamelin and Isabel in 1189-90, and dedicated to St Philip and St James (although there was a, now lost, second chapel in the inner bailey to which the endowment could refer). The chapel is well-decorated, with quatrefoil windows, elaborate carving on the columns and a wonderful vaulted ceiling.

There is a small sacristy for the priest, just to the left of the door, with another basin for the priest’s personal use, and cavities for storing the vestments and altar vessels.

The winding stairs, built within the keep’s thick walls, give access to each successive level and, eventually, to the battlements, with a panoramic view of the surrounding area.

These battlements also had cisterns to hold rainwater, a bread oven and weapons storage; and wooden hoardings stretching out over the bailey to aid in defence. The keep and curtain walls – which were built slightly later – were of a state-of-the art design in their day. The barbican, leading into the inner bailey, had 2 gatehouses and a steep passageway guarded by high walls on both sides; an attacking force would have been defenceless against missiles from above, with nowhere to run in the cramped corridor.

Although the encircling moat is dry (the keep is built high on a hill), all the detritus from the toilets and kitchens drained into it; another little aid to defence – imagine having to attack through that kind of waste?

None of the buildings in the inner bailey have survived, although you can see their stone foundations in the ground. Along one wall there were kitchens and service rooms leading into a great hall, with a raised dais at the far end, and a solar and living quarters above. Another range of buildings attached to the western wall also held living quarters, possibly for the garrison and any guests. There’s even a small jail cell just to the side of the barbican.

Although Conisbrough is not a large castle, the extensive range of buildings, the magnificent decorations of the fireplaces and chapel, suggest it would have been impressive in its day; and reflects the importance of the castle’s owners and occupants.

*

The Castle’s Residents

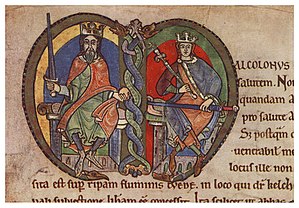

The Warenne Earls of Surrey were close to the crown, and the centre of government, for the best part 3 centuries. The daughter of the 2nd Earl, Ada, had married the heir to the Scots throne and was mother to 2 Scottish kings; Malcolm the Maiden and William the Lion.

Hamelin’s son and heir, William, 5th Earl of Warenne and Surrey, married Maud Marshal, daughter of the Greatest knight, William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke and Regent during Henry III’s infancy. A cousin of King John, William was deeply involved in the Magna Carta crisis, though not always in support of his cousin. Their son John, the 6th Earl, was Edward I’s lieutenant in Scotland and beat the Scots at the Battle of Dunbar in 1296, though he had been defeated by William Wallace at Stirling Bridge the following year. John’s daughter, Isabella, married John Balliol, King of Scots, and was mother to Edward Balliol, another Scottish king. John’s sister, Isabel, married Hugh d’Aubigny, 5th Earl of Arundel, and is remembered as the countess who stood up to Henry III, invoking Magna Carta, when he appropriated land that was rightfully hers.

The 7th – and last – Warenne earl, John, was a colourful character who lived through some of the most dramatic events of English history; the reign of Edweard II. John was the grandson of the 6th earl; his father, William de Warenne, had diedbeen killed in a tournament at Croydon, in December 1286, when John was just 6 months old. Although he was married to Joan of Bar, a granddaughter of Edward I, John lived openly with his mistress and made several unsuccessful attempts to obtain a divorce from his wife. A private feud with Thomas Earl of Lancaster saw John arrange the kidnapping of Earl Tomas’ wife, Alice de Lacey, possibly in retaliation for Lancaster standing in the way of Surrey’s longed-for divorce. The result was the 1st – and only – siege of Conisbrough Castle.

Lancaster sent forces to seize the Warenne castles at Sandal and Conisbrough. His men found the gates of Conisbrough closed to them. The castle was defended by only six men, including the town miller and three brothers, Thomas, Henry and William Greathead, who were men-at-arms. The siege lasted less than two hours and the defenders appear to have relinquished the castle after apparently putting up a token resistance; the three brothers were fined for drawing blood. The chapel in the castle’s inner bailey may have been damaged in the brief altercation, as the following year, Lancaster sent orders to his castellan at Conisbrough, John de Lassell, to ‘repailler la couverture de la chapele de Conynggesburgh.’1

The last Earl of Surrey died without heirs in 1347 and Conisbrough passed to John de Warenne’s godson, Edmund of Langley, fourth son of Edward III. Edmund’s wife Isabella of Castile gave birth to her 3rd child, Richard Earl of Cambridge (also known as Richard of Conisbrough) at Conisbrough, possibly in the lavish bedchamber within the keep itself. Cambridge had the dubious reputation of being England’s poorest Earl and was executed following his involvement in the Southampton plot against Henry V; however, he is remembered to history as the grandfather of the Yorkist kings, Edward IV and Richard III.

Following Cambridge’s execution for treason in 1415 his 2nd wife, Maud Clifford, made Conisbrough her principal residence until her death in 1446. Maud entertained her Clifford family here and her great-nephew and godson John Clifford, known to Yorkists as the Butcher of Skipton was born there in 1435. In a strange twist of fate, John Clifford is the one accused of murdering the Earl of Cambridge’s 17-year-old grandson Edmund, Earl of Rutland, following the Lancastrian’s defeat of the Yorksists at the Battle of Wakefield on 30 December 1460. Maud died at the castle in August 1446 and is buried in Roche Abbey, about 10 miles from her home.

The castle underwent repairs during the reigns of Edward IV and Richard III, in 1482-3, but by 1538 a survey revealed the it had fallen into neglect and decay, with parts of the curtain wall having slipped down the embankment.

From then on, although it has had successive owners until it came under the protection of English Heritage, Conisbrough Castle has been a picturesque ruin, a wonderful venue for picnics and exploring its many hidden treasures.

*

All photographs are copyright to Sharon Bennett Connolly, 2015.

Footnote:

1 Hunter’s South Yorkshire ii; Deanery of Doncaster ii quoted in F. Royston Fairbank, The Last Earl of Warenne and Surrey, and the Distribution of His Possessions, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, p. 213

*

Sources:

Further reading: East Yorkshire Charters Volume 8: The Honour of Warenne, edited by William Farrer & Charles Travis Clay; English Heritage Guidebook for Conisbrough Castle by Steven Brindle and Agnieszka Sadrei; English Tourist Board’s English Castles Almanac; The English Medieval House by Margaret Wood; http://www.kristiedean.com/butcher-skipton; On the Trail of the Yorks by Kristie Dean; F. Royston Fairbank, The Last Earl of Warenne and Surrey, and the Distribution of His Possessions, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal.

*

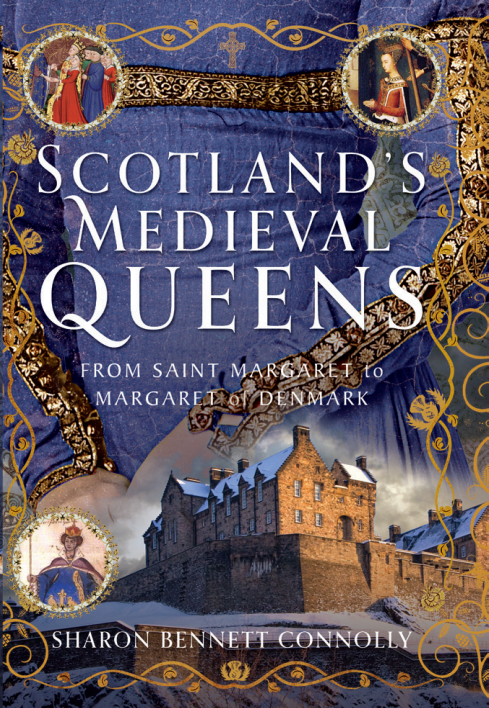

My Books

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, of the successes and failures of one of the most powerful families in England, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III.

1 family. 8 earls. 300 years of English history!

Defenders of the Norman Crown: Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey will be released in the UK on 31 May and in the US on 6 August. And it is now available for pre-order from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US and Book Depository.

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available from Pen & Sword, Amazon and from Book Depository worldwide.

Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon and Book Depository.

Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, Book Depository.

*

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

©2020 Sharon Bennett Connolly