When John Lovell VII, Lord Lovell and Holland died on 10 September 1408 at the age of about 66 he had lived not only a long but also a very active and occasionally turbulent life.

John Lovell VII, who is generally referred to as the fifth Lord Lovell, came of age in 1363 and on 8 June the escheators of several counties were ordered to give him seisin of his lands. At this point, the fortunes of his family were at a distinctly low point. His great-grandfather John Lovell III had been the first Lovell to be summoned to parliament and once had been the marshal of Edward I’s army in Scotland. It was the death of his son, John Lovell IV, at the battle of Bannockburn on 24 June 1314, only four years after his father died, that started the long time of decline. First came the long minority of his posthumous son John Lovell V. John Lovell V died at the young age of 33 on 3 November 1347. Another long period of guardianship followed as his eldest son, John Lovell VI was only six years old when his father died. Isabel, the wife of John Lovell V, died two years after her husband in 1449 only a year after the death of Joan de Ros, the grandmother of John Lovell V. This meant that all the Lovell estates were in the hands of guardians. The long periods of guardianship must have surely have a detrimental effect on the profitability of the Lovell estates. Additionally, the lands were also devastated by the Plague. In Titchmarsh, for example, only four of the eight tenants survived the Plague. John Lovell VI died a minor on 12 July 1361 and his younger brother, John Lovell VII, who was also underage, inherited his lands.

Though John Lovell VII was able to look back to a long line of distinguished ancestors, when he was declared of age in 1463, for thirty-nine years of the previous 49 years, the head of the Lovell family had been a minor. His father had never been summoned to parliament, nor had, needless to say, his elder brother. John Lovell VII certainly could not rely on family influence to make his way to promotion and it was even uncertain whether he would receive an individual summons as his great-grandfather and grandfather had done.

Fortunately John Lovell VII was an ambitious young man, who would prove himself to be an able military commander and administrator. He was also, as far as we can tell, able to make fast friends and allies. Last but not least, he was also lucky.

He first appears in records serving on several military campaigns including in Brittany and was in the company of Lionel, Duke of Clarence, when he was travelling to Milan to marry Violante Visconti. It was most likely in this early period of his life that he went on crusade to Prussia and the Eastern Mediterranean.

Though we do not know exactly when he married Maud Holland, the granddaughter and heiress of Robert Holland, but it was probably in 1371, when Maud was about 15. As an heiress of her grandfather large estates, this was an exceptionally good match for a young man with few connections. Interestingly, this marriage not only approximately doubled the lands John Lovell was holding, it also created a link, if only a tenuous one to the royal family. Maud Holland’s grandfather Robert Holland was the older brother of Thomas Holland, who in turn was the husband of Joan of Kent. Maud Holland’s father Robert, who had predeceased his father, therefore had been the cousin of Thomas, John, Maud, and Joan Holland, the half-siblings of Richard II.

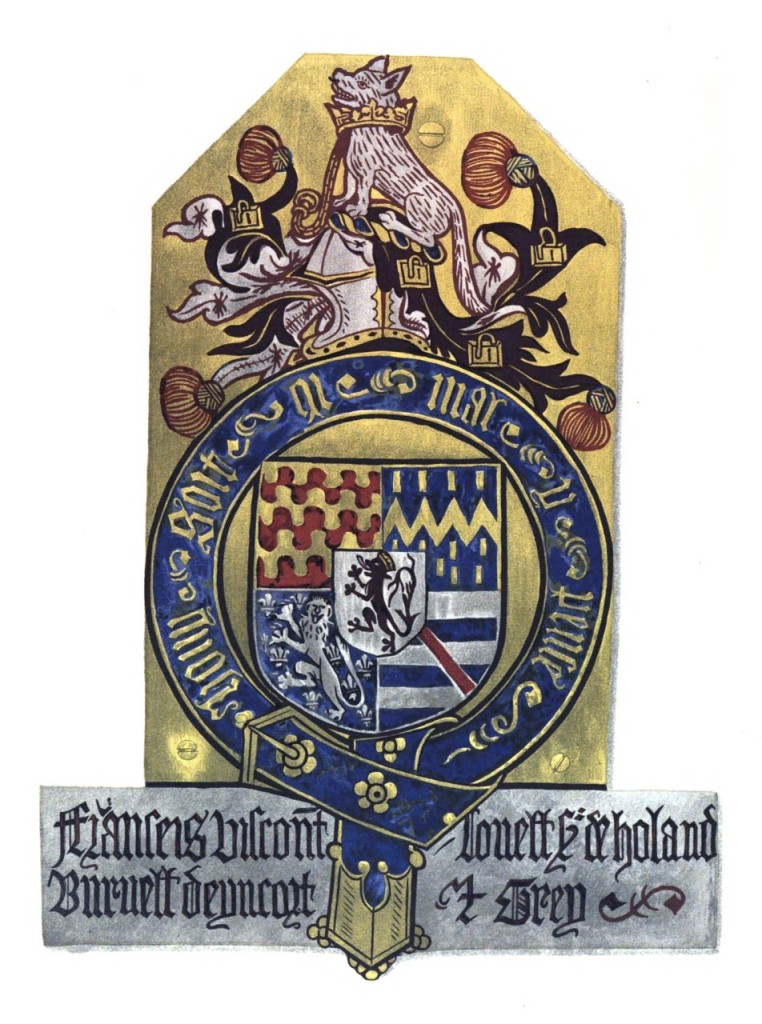

Thanks to his marriage to Maud Holland, John Lovell VII held both the Lovell and the Holland barony. John Lovell certainly seems to have appreciated the significance of this marriage: he was the first noblemen who used a double title, calling himself Lord Lovell and Lord Holland. He also combined the Lovell coat of arms with that of the Holland. On their seals, John Lovell VII, his wife Maud Holland, and their sons John Lovell VIII and Robert Holland showed the quartered Lovell and Holland coat of arms. The design can also be found in the cloister of Canterbury Cathedral to the present day.

It is perhaps no accident that the first parliament John Lovell VII was summoned to was the first parliament to be held after his wife’s grandfather had died and he had taken control of his wife’s inheritance. Significant though this boost to his wealth no doubt was, John Lovell VII had also demonstrated his willingness and ability to serve in the military in the years since he came of age. His period as a crusader certainly must have added to his fame as well. The fact that his ancestors had already received individual summonses alone may not have been enough to ensure his inclusion in the House of Lords, but a combination of all these factors made certain of it.

Over the following 33 years John Lovell VII served in a variety of functions, both in military service and increasingly also in the royal administration. Like all noblemen he was appointed to commissions in the areas where his estates were concentrated. He was also placed on commissions that were appointed to deal with more general problems. In 1381, in the aftermath of the Peasants’ Revolt, John Lovell served on a commission to deal with crimes committed during the uprising. John Lovell must have got to know several of his fellow commissioners quite well, as he met them frequently both in the localities and at court. Whether this acquaintances also became his friends is difficult to impossible to say.

In 1385, the war between England and Scotland broke erupted again, and John Lovell VII joined the exceptionally large army that Richard II led north. It was during this campaign that John Lovell started a dispute with Thomas, Lord Morley about the right to bear the arms argent, a lion rampant sable, crowned and armed or. Disputes about who was the rightful owner of a particular coat of arms were quite common in this period. However, only in three of these cases substantial records of the proceedings have survived to this day. One is the Lovell-Morley dispute, the other two are the contemporary controversy between Richard Scrope and Robert Grosvenor, and the slightly later case of Reginald, Lord Grey of Ruthin and Sir Edward Hastings. The Lovell-Morley dispute is an interesting case, as the coat of arms that John Lovell claimed were not in fact the Lovell coat of arms (barry nebuly or and gules). The arms John Lovell claimed were those that his (half-)uncle Nicholas Burnell had fought over with the grandfather of Thomas Morley, Robert Morley, during the Crécy-Calais campaign almost forty years earlier. A considerable part of the testimony collected in the records of the Morley-Lovell dispute is therefore about the earlier proceedings.

The question that this case raises is of course why John Lovell VII claimed to be the rightful owner of the Burnell coat of arms. The most likely explanation is that he used the claim to the Burnell coat of arms to also stake his claim on the Burnell barony. His grandmother Maud Burnell had settled most of these estates on her sons from her second marriage with John Haudlo. By claiming the Burnell coat of arms, he showed he considered himself the rightful heir of the Burnell barony.

Unfortunately, the outcome of this case cannot be found in the records of the court case. Later depictions of the coat of arms used by Hugh Burnell, John Lovell VII (half-)cousin, shows them differenced with a blue border. John Lovell VII himself continued to use the quartered Lovell and Holland arms as before.

In the course of the 1380s John Lovell VII became a well-placed courtier and administrator. He was made a king’s knight and banneret of the royal household. He also received rewards for his service. When the disagreements between Richard II and several high-ranking members of the nobility worsened at the end of the decade, John Lovell was at first trusted by both sides of the conflict and was employed as an intermediary. But by the time of the Merciless Parliament, he had lost the trust of the king’s critics. He was expelled from court alongside 14 other men and women during the Merciless Parliament and had to swear not to return. Though the exact charges against the men and women thus removed from court are not known, they were considered to have had only undue influence over the king. John Lovell VII exile from court was short as he had returned by the following year. It is possible that his friendship to Bishop Thomas Arundel, the brother of one Richard II’s fiercest critics, eased his way back.

Far from discourage John Lovell VII became even more influential at court during the following decade. He became a member of the king’s council and the number of royal charters he witnessed increased. In 1395, Richard II retained him for life.

It was in 1393, John Lovell VII received a licence to crenellate his manor in Wardour (Wiltshire). The castle he built, now Old Wardour Castle, is of an unusual hexagonal design and despite its appearance are that of a fortress, it was mainly built for comfort and entertainment. Though the building was severely damaged during the Civil War, the ruins are still impressive and give an impression on the amount of money, John Lovell spent on its building.

John Lovell accompanied Richard II on both his expeditions to Ireland. When Richard’s cousin Henry of Bolingbroke invaded England while Richard was in Ireland in 1399, John Lovell stayed with the king even after he had sent most of the army back to England. By the time Richard, his remaining troops and household finally sailed for Wales, it was already too late.

Unfortunately, what exactly happened next cannot be pieced together with certainty as the chronicles describing the events are too vague. We know that soon after landing in Wales, Thomas Percy, Earl of Worcester, Edward, Duke of Aumale, John Stanley, controller of the royal household and John Lovell VII left Richard II and met up with Henry of Bolingbroke, either in Shrewsbury or Chester. Here they ‘put themselves at his mercy’. Considering that all four men had been favoured and promoted by Richard II, this looks like a case of blatant ungratefulness. However, at this time everybody vividly remembered what had happened during the last crisis of Richard II’s reign: all of his supporters that had not managed to escape abroad or were clergymen had been executed. It seems likely that John Lovell and the others tried to escape a similar fate.

Whatever his personal feelings were, John Lovell VII quickly made his peace with the new government. He did not participate in the Epiphany Rising that tried to place Richard II on the throne again and was quickly back in his old position at court. That he had gained the

trust of Henry IV was soon obvious, as John Lovell was one of the four men who were considered to become the tutor of Henry, Prince of Wales. Though he was not appointed in the end, he retained his place on the council. In February 1405 his long service to the Crown was rewarded when he was made Knight of the Garter. Though he was getting on in years, he still participated in the campaign in Wales in the same year. He died three years later on 10 September 1408.

The writs to hold the inquisitions post mortem about the estates he held were sent out to the various counties from Westminster a day later, on 11 September. The only exception is the writ to the escheator of Rutland, which was only written on 16 February 1409, presumably because it had been unknown John Lovell held land there.

It has been argued, though unfortunately I cannot remember where, that this quick response to his death meant that he had been ill for some time and his death was expected. The one record that specifies where John Lovell died, the inquisition taken in Lincoln on 25 September, state that he died at Wardour Castle in Wiltshire. I have to say that I have serious doubts that it was physically possible for the news of his death to travel the distance of over 100 miles from Wardour to Westminster in a single day. Even if John Lovell’s death had been expected it would still be necessary for someone to inform the administration that he had died so that the inquisitions post mortem could be sent out. It seems more likely to me that the information taken by the escheator in Lincoln was faulty, perhaps it was assumed that John Lovell would have been in Wardour Castle. The quickness with which the writs were issued, suggests to me that John Lovell died in London, probably at Lovell’s Inn in Paternoster Row.

John Lovell VII was buried in the church of the Hospital of St James and St John near Brackley. The church had had no previous connection to the Lovell family, but it was the burial place of Robert Holland, the grandfather of John Lovell’s wife Maud, and her great-grandfather, another Robert. This decision was another indication of how important his marriage was for John Lovell.

John Lovell VII had taken the fortunes of the Lovell family from a rather low point to a new height. He achieved this by luck, through his marriage to the heiress Maud Holland, dedicated service in war and peace, and through his skill to survive turbulent times like the Merciless Parliament or the usurpation of Henry IV. He could be accused of being a ruthless opportunist, but, to quote Mark Ormrod (in his masterful biography of Edward III): ‘the men who survived and thrived in the prince’s service, were precisely those who had the wit and judgement to adjust to the dramatic shifts in political fortunes.’ Though this refers to the last years of the reign of Edward II it also holds true for the turbulent times John Lovell VII lived through.

About the Author:

Monika E. Simon studied Medieval History, Ancient History, and English Linguistics and Middle English Literature at the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich, from which she received an MA. She wrote her DPhil thesis about the Lovells of Titchmarsh at the University of York. She lives and works in Munich.

Links:

https://www.pen-and-sword.co.uk/From-Robber-Barons-to-Courtiers-Hardback/p/19045

https://www.facebook.com/MoniESim

http://www.monikasimon.eu/lovell.html

*

My Books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available, please get in touch by completing the contact me form.

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, of the successes and failures of one of the most powerful families in England, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Defenders of the Norman Crown: Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey is now available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US and Book Depository.

1 family. 8 earls. 300 years of English history!

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available from Pen & Sword, Amazon and from Book Depository worldwide.

Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon and Book Depository.

Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, Book Depository.

*

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

©2021 Sharon Bennett Connolly and Monika E Simon