Today it is a pleasure to welcome author Monika E Simon back to the blog, with an article looking at the origins of the Lovell family. Monika’s book, From Robber Barons to Courtiers: The Changing World of the Lovells of Titchmarsh, will be released on 30 June. Over to Monika:

How to make your fortune and get your name into the history books?

In my last blogs I have talked about events from the last century of the history of the Lovell of Titchmarsh. Today I am going back to their very beginnings of this English noble family. So far back in fact that they had not arrived in England and were not called Lovell. At the time, the second half of the eleventh century, the ancestors of the family were obscure minor lords at the Norman French border about whom we know nothing beyond their names and a few details about lands they possessed or office they held. This all changed with Ascelin Goël, who was, as the Complete Peerage puts it, ‘undoubtedly the true founder of the family fortunes.’ He turned his family from an minor nobles into powerful border lords.

How did Ascelin Goël achieved this? Not as the reward for faithful service to his lord, but through rebellion and violence. His behaviour was outrageous enough, even in a time not short on violent men, for the chronicler Orderic Vitalis to write about Ascelin Goël’s deeds in his Ecclesiastical History.

For many events, this chronicle is the only source. Fortunately, Orderic Vitalis was exceptionally well placed to know what he was writing about. He was a monk at the monastery of St Evroult (Dept. Orne, Normandy) and in the latter part of his chronicle he describes events that happened in his own lifetime and often not very far from where he lived. His Ecclesiastical History is, as J.O. Prestwich writes ‘of exceptional value for the history of the Anglo-Norman world’. The way he orders the events in his chronicle is, however, not without severe drawbacks, as he was ‘remarkably careless of chronology’ (Prestwich again). The confusing structure means that the events in which Ascelin Goël was involved in are described in different parts of the chronicle and it is often difficult or impossible to be certain what happened when. Since Orderic Vitalis is mostly the only source existing it is also not possible to check his report or fill in any information his chronicle omits to mention. Nonetheless it is possible to reconstruct the story and draw some probably conclusions.

Ascelin Goël was the eldest son of Robert d’Ivry and Hildeburge de Gallardon. Both of his parents entered religious houses towards the end of their lives and Hildeburge de Gallardon acquired a reputation for heir piety. A brief description of her life, the Vita Domine Hildeburgis, was written, perhaps as a first step to have her canonized. There is however no evidence that this was pursued any further.

Ascelin Goël’s father Robert d’Ivry held land around Bréval and Ivry on both sides of the French Norman border. He was castellan of the border Castle of Ivry (in modern-day Ivry-la-Bataille, Dept. Eure) in 1059. Robert’s mother was probably Aubrée, daughter of Hugh, Bishop of Bayeux and therefore granddaughter of Ralph, Count of Bayeux and his wife Aubrée. According to Orderic Vitalis it was Aubrée who had the architect Lanfred build the Castle of Ivry. If Ascelin Goël’s grandmother was indeed Aubrée, daughter of Hugh, Bishop of Bayeux, he was for one indirectly related to the ducal family, as Aubrée’s grandfather Ralph Count of Bayeux was a half-brother of Richard I of Normandy. It would also mean that Ascelin Goël was related to William de Breteuil, his lord and great opponent, as William’s grandmother Emma was a sister of bishop Hugh. Moreover, Ascelin’s descend from the woman who built the Castle of Ivry would give him a hereditary claim on the castle.

Ascelin Goël had in fact set his sight on the Castle of Ivry, a mighty border fortress and possibly the model for the White Tower in London. At the time, castles were centres of power and much coveted by the nobility. Particularly desirable were the castles that guarded the borders of England against Wales and Normandy against France. Possessing one of these border castles gave the owner both power and an unusual amount of freedom, especially if they were held them in their own right and not as castellans appointed by their king or duke. Many noblemen used any means, fair or foul to gain full control of one or more of these castles. They used any opportunity to achieve this goal, and in 1087, after the death of William the Conqueror, the nobles en masse expelled the royal garrisons from their castles.

Until then the Castle of Ivry had been in the hand of the dukes of Normandy. William the Conqueror had appointed Roger Beaumont as the castellan, probably after Robert d’Ivry had joined a religious community. When Robert Curthose became Duke he granted the castle to William de Breteuil, who was one of his long-standing supporters. To appease Roger Beaumont, Robert Curthose gave him the Castle of Brionne as compensation.

William de Breteuil was a grandson of Osbern, the steward of duke Robert the Magnificent. He had not inherited all the lands of his father William fitz Osbern, but enough to become one of the most powerful nobleman in Normandy. After gaining possession of Ivry he made Ascelin Goël castellan of the castle. As it turned out, Ascelin Goël was not satisfied with merely holding the castle for another lord. Two years after becoming castellan of Ivry, he took control of the castle, presumably by expelling William de Breteuil’s men and replacing them with his own.

An interesting aspect of this conflict is that Ascelin Goël took on not only his lord but also a nobleman who was so much more powerful than he himself was. Ascelin Goël was only a minor border lord whose man residence was in Bréval (Dept. Yvelines). Here he had built a strong castle that he had filled ‘with cruel bandits to the ruin of many’, according to Orderic Vitalis.

After gaining control of Ivry, Ascelin Goël handed it over to Duke Robert. It is possible that he hoped his hereditary claim to the castle would move Robert Curthose to grant it to him. If that was the case, he was mistaken, as Robert Curthose sold it back to William de Breteuil.

Unsurprisingly, William de Breteuil was far from pleased with his castellan and deprived Ascelin Goël not only of his castellanship but of all the lands Ascelin had held off him.

For Ascelin Goël this was a setback but he did not give up. In 1091, he was able to capture William de Breteuil, with the help of Richard of Montfort and household troops of King Philip I of France. William de Breteuil now found himself incarcerated for three months at Bréval and subjected to various forms of torture. Once, Orderic Vitalis writes, Ascelin Goël had his prisoners exposed to the freezing wind clad only with wet shirts until these were frozen solid. After three months of imprisonment, William’s release was secured by a truce arranged by several noblemen. He had to pay a heavy price for his freedom. He had to give the Castle of Ivry to Ascelin Goël and pay a hefty ransom in money, horses, arms and ‘other things’. Additionally, William de Breteuil had to give Ascelin his illegitimate daughter Isabel as his wife. – Needless to say, what Isabel thought of this was not recorded.

However, Ascelin Goël was not able to enjoy possessing Ivry for long. The year after his release William de Breteuil first tried to retake Ivry. He failed and barely escaped being recaptured by Ascelin Goël, who again tortured the prisoners he had taken. The next year William de Breteuil was better prepared. With the support of Robert Curthose and King Philip of France, both of whom he had to pay for their help, he tried again to take Ivry back. He had also gained the support of the experienced warrior Robert de Bellême who led the siege of Ascelin Goël’s Castle of Bréval. Ascelin was able to withstand the siege for two months but eventually had to surrender and hand the Castle of Ivry back to William de Breteuil.

Having lost Ivry again, Ascelin Goël seems to have realised that for now he had no chance to hold the castle permanently against William de Breteuil. With Isabel de Breteuil as his wife, Ascelin Goël also had a better claim to inherit the castle after William de Breteuil’s death. William had no legitimate children, only an illegitimate daughter Isabel and an illegitimate son Eustace. As inheritance law was not yet strictly settled in this time, Isabel, Eustace, and several more distant relations could claim William de Breteuil’s lands or part of them after his death.

When William de Breteuil died on 12 January 1203, Ascelin Goël was in fact one of them men fought Eustace de Breteuil for possession of William de Breteuil’s lands. The two most prominent claimants were William Gael, a nephew of William de Breteuil, and a more distant relative the Burgundian Reginald de Grancey. Eustace had previously gained the goodwill of Henry I of England by supporting him in driving Robert de Bêlleme out of England and had married Henry I’s illegitimate daughter Juliana. Moreover, the Norman nobility largely supported Eustace, ‘because’, as Orderic Vitalis explains, ‘they chose to be ruled by a fellow countryman who was a bastard rather than by a legitimate Breton or Burgundian’.

Ascelin Goël is usually mentioned in this conflict, but he is not regarded as a rival claimant to the Breteuil in inheritance. However, Orderic Vitalis singles him out particularly. He writes that Henry I promised to support Eustace ‘against Goel and all his other enemies’. To me it seems significant that it is Ascelin Goël rather than Reginald de Grancey whom Orderic names as Eustace principal enemy.

To solve this crisis, Henry I sent his chief advisor Robert Beaumont, Count of Meulan to Normandy. Robert Beaumont soon had a personal reason to find a solution, as Ascelin Goël kidnapped John, a citizen from Meulan, when he was on his way back from a meeting with Robert Beaumont. John de Meulan was imprisoned in Bréval and for four months Robert Beaumont was unable to rescue him. Eventually Robert Beaumont was able to arrange a peace between all parties. Orderic Vitalis reports that he betrothed his baby daughter Emma to Amaury de Montfort, which appeased not only Amaury himself but also his uncle William, Count of Évreux, Ralph of Conches, Eustace de Breteuil, and Ascelin Goël. Orderic Vitalis does not mention any specific concessions made to Ascelin Goël. Later evidence suggests that Ascelin Goël gained what he had strived to gain for more than ten years: the Castle of Ivry. A charter of 1115 calls Ascelin Goël ‘Goelli de Ibriaco’, Goël of Ivry, and at no other time Ascelin Goël was in the position to achieve this concession from Eustace de Breteuil.

From this time on, Ascelin Goël kept his peace until his death between 1116 and 1119. At least he refrained from engaging in feuds with his powerful neighbours. Orderic Vitalis writes that he and his sons continued to plague the region with their violence and cruelty.

To answer the question I have asked at the beginning of this blog: How did one make one’s fortune and got one’s name into the history books? Ascelin Goël’s answer was by rebellion and violence. His disregard from the bonds of feudal lordship, his cruelty and ruthlessness ensured him a place in Orderic Vitalis’s Ecclesiastical History and from there in history books to the present day. He also probably gained the Castle of Ivry and became a much more powerful lord than his father and grandfather had been.

Though Robert Goël, Ascelin Goël’s eldest son, did not inherit the Castle of Ivry, he did inherit his ruthless streak and tactical skill. He joined the rebellion against Henry I in 1118 but was the first rebel to make his peace with the king in 1119. In return and ‘to guarantee his loyalty’, to quote Orderic Vitalis one last time, Henry I granted Robert Goël the Castle of Ivry. Robert Goël’s younger brother, William Lovell I, inherited the castle after his brother’s death in or shortly before 1123.

Images:

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons except William fitz Osbern and the author at Chepstow Castle, 2007 which is courtesy of Kirsty Hartsiotis

About the author:

Monika E. Simon studied Medieval History, Ancient History, and English Linguistics and Middle English Literature at the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich, from which she received an MA. She wrote her DPhil thesis about the Lovells of Titchmarsh at the University of York. She lives and works in Munich.

Links:

https://www.pen-and-sword.co.uk/From-Robber-Barons-to-Courtiers-Hardback/p/19045

https://www.facebook.com/MoniESim

http://www.monikasimon.eu/lovell.html

*

My Books:

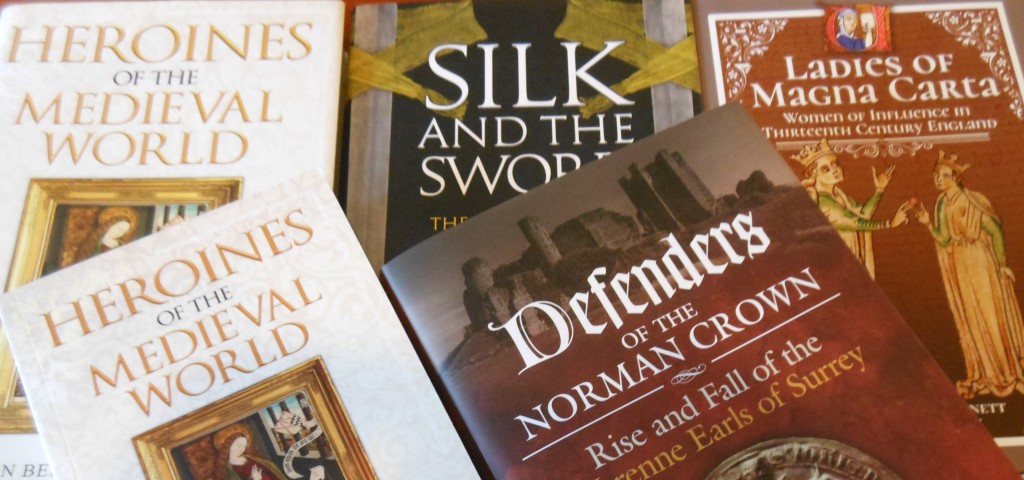

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, of the successes and failures of one of the most powerful families in England, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III.

1 family. 8 earls. 300 years of English history!

Defenders of the Norman Crown: Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey will be released in the UK on 31 May and in the US on 6 August. And it is now available for pre-order from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US and Book Depository.

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available from Pen & Sword, Amazon and from Book Depository worldwide.

Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon and Book Depository.

Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, Book Depository.

*

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

©2021 Sharon Bennett Connolly and Monika E Simon

One thought on “Guest Post: How to make your fortune and get your name into the history books? by Monika E Simon”