The story of Eleanor of Brittany is one that highlights how women in the Middle Ages could feel truly powerless, if the men around them wanted it so. Her story also highlights the limitations of the Great Charter, or Magna Carta as it is better known, in protecting and supporting the rights of women – even princesses. Eleanor was born around 1184; she was the daughter of Geoffrey Plantagenet, Duke of Brittany by right of his wife, and Constance of Brittany. Described as beautiful, over the years she has been called the Pearl, the Fair Maid and the Beauty of Brittany.

A granddaughter of the medieval power couple, Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine, she was the eldest of her parents’ three children; Matilda, born the following year, died young and Arthur, born in spring 1187, six months after his father’s death in a tournament near Paris. Arthur was killed by – or at least on the orders of – King John in 1203.

Initially, Eleanor’s life seemed destined to follow the same path as many royal princesses; marriage. Richard I, her legal guardian after the death of her father in 1186, offered Eleanor as a bride to Saladin’s brother, Al-Adil. Eleanor’s aunt, Joanna, King Richard’s sister had adamantly refused to consider such a marriage and so Eleanor had been offered as an alternative. This was part of an attempt at a political settlement to the 3rd Crusade that never came to fruition.

At the age of 9, Eleanor was betrothed to Friedrich, the son of Duke Leopold VI of Austria. Duke Leopold had made the betrothal a part of the ransom for Richard I’s release from imprisonment. Young Eleanor travelled to Germany with her grandmother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, and the rest of the ransom and hostages. She was allowed to return to England, unmarried, when Duke Leopold died suddenly, and his son had ‘no great inclination’ for the proposed marriage. Further marriage plans were mooted in 1195 and 1198, to Philip II of France’s son, Louis, and Odo Duke of Burgundy, respectively; though neither came to fruition.

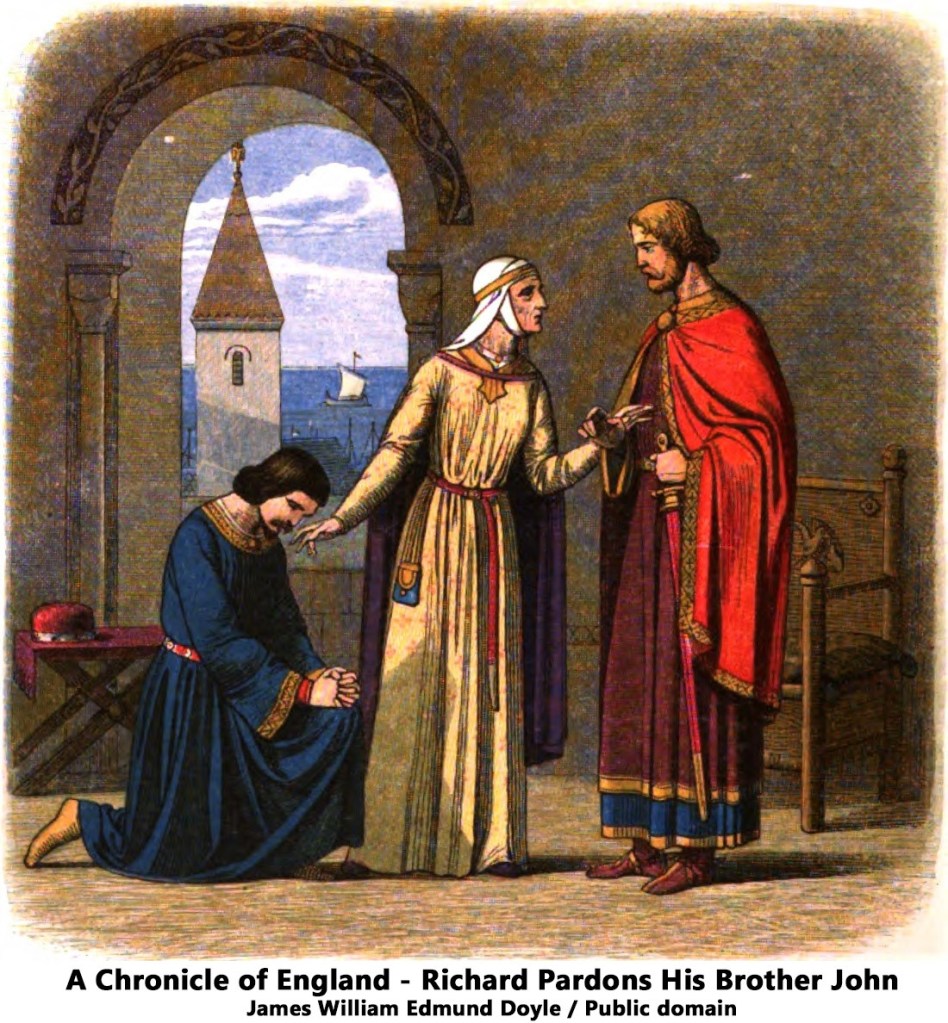

Eleanor’s fortunes changed drastically when Arthur rebelled against Richard’s successor, King John, in the early 1200s. As the son of John’s older brother, Geoffrey, Arthur had a strong claim to the English crown, but had been sidelined in favour of his more mature and experienced uncle. Arthur was captured while besieging his grandmother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, at Mirebeau on 1st August 1202. Eleanor was captured at the same time, or shortly after. And while her brother was imprisoned at Falaise, she was sent to England, to what would be a life-long imprisonment.

If the laws of primogeniture had been strictly followed at the time, Eleanor would have been sovereign of England after her brother’s death. John and his successor, Henry III could never forget this. However, primogeniture was far from being the established rule of succession that it is today. Further, the experiences of Empress Matilda and her fight with King Stephen over her own rights to the crown – and the near-20 years of civil war between 1135 and 1154, had reinforced the attitude that a woman could not rule.

Not only was Eleanor her brother Arthur’s heir, but with King John still having no legitimate children of his own, she was also the heir to England and would be until the birth of John’s eldest son, Henry, in October 1207. If the laws of inheritance had been strictly followed, Eleanor would have been sovereign of England after her brother’s death: John and his successor, Henry III, could never forget this. In 1203 she was moved to England and would be held a prisoner of successive English kings to her dying day. Although her confinement has been described as ‘honourable’ and ‘comfortable’, Eleanor’s greater right to the throne meant she would never be freed or allowed to marry and have children, despite repeated attempts over the years by King Philip and the Bretons to negotiate her release.

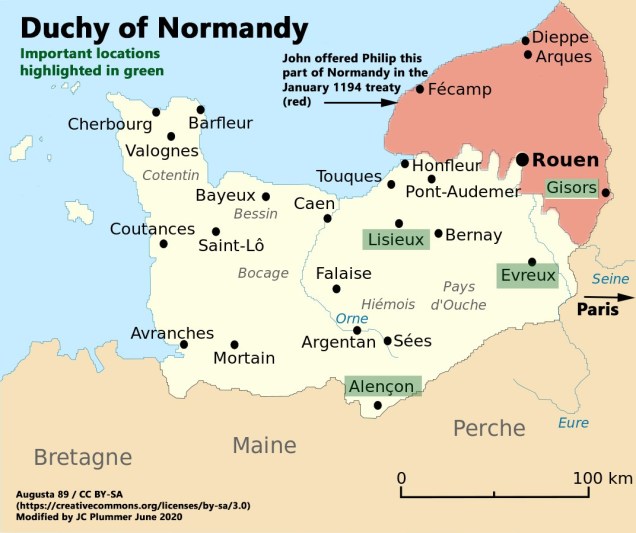

It seems Eleanor did spend some time with the king and court, particularly in 1214 when she accompanied John to La Rochelle to pursue his war with the French. John planned to use Eleanor to gain Breton support and maybe set her up as his puppet duchess of Brittany, replacing her younger half-sister Alice. Alice was the daughter of Eleanor’s mother, Constance, by her third marriage to Guy of Thouars. She was married to Peter of Dreux, a cousin of King Philip of France and duke of Brittany by right of Alice. Using the carrot and stick approach, John offered Peter the earldom of Richmond to draw him to his side, while at the same time dangling the threat of restoring Eleanor to the dukedom, just by having her with him. Peter, however, refused to be threatened or persuaded and chose to face John in the field at Nantes. John’s victory and capture of Peter’s brother in the fighting persuaded Peter to agree to a truce, and John was content to leave Brittany alone, thereafter, instead advancing on Angers. His plans to restore Eleanor abandoned and forgotten.

As John’s prisoner, Eleanor’s movements were restricted, and she was closely guarded. Her guards were changed regularly to enhance security, but her captivity was not onerous. She was provided with ‘robes’, two ladies-in-waiting in 1230, and given money for alms and linen for her ‘work’.1 One order provided her with cloth; however, it was to be ‘not of the king’s finest.’2 Eleanor was well-treated and fed an aristocratic diet, as her weekly shopping list attests: ‘Saturday: bread, ale, sole, almonds, butter, eggs. Sunday: mutton, pork, chicken and eggs. Monday: beef, pork, honey, vinegar. Tuesday: pork, eggs, egret. Wednesday: herring, conger, sole, eels, almonds and eggs. Thursday: pork, eggs, pepper, honey. Friday: conger, sole, eels, herring and almonds.’3

Eleanor was granted the manor of Swaffham and a supply of venison from the royal forests. The royal family sent her gifts and she spent some time with the queen and the daughters of the king of Scotland, who were also hostages in the king’s custody after July 1209. King John gave her the title of Countess of Richmond on 27 May 1208, but Henry III’s regents would take it from her in 1219 and bestow the title elsewhere. From 1219 onwards she was styled the ‘king’s kinswoman’ and ‘our cousin’. In her sole surviving letter, written in 1208 with John’s consent, she is styled ‘Duchess of Brittany and Countess of Richmond.’4 Throughout her captivity she is said to have remained ‘defiant’.5

It is difficult to pinpoint exactly where Eleanor was imprisoned at any one time. Over the years, she was held in various strongholds, including the castles of Corfe (Dorset), Burgh (Westmorland), and Bowes (Yorkshire). Corfe Castle is mentioned at various times, and it seems she was moved away from the is fortress on the south coast in 1221, after a possible rescue plot was uncovered. She was also held at Marlborough for a time, and was definitely at Gloucester castle in 1236. By 1241 Eleanor was confined in Bristol castle, where she was visited regularly by bailiffs and leading citizens to ensure her continued welfare. Eleanor was also allowed her chaplain and serving ladies to ensure her comfort.

Eleanor of Brittany died at Bristol Castle, on 10 August 1241, at the age of about 57, after thirty-nine years of imprisonment, achieving in death, the freedom that had eluded her in life. She was initially buried at St James’s Priory church in Bristol but her remains were later removed to the abbey at Amesbury, as instructed in her will; a convent with a long association with the crown.

The freedoms and rights enshrined in Magna Carta in 1215, and reissued in 1216 and 1225 under Henry III, unfortunately held no relevance or respite for Eleanor. Every other subject of the king was afforded the right to judgement of his peers before imprisonment thanks to clause 39:

“No man shall be taken, imprisoned, outlawed, banished or in any way destroyed, nor will we proceed against or prosecute him, except by the lawful judgement of his peers or by the law of the land.”

Magna Carta 1215

And clause 40:

“To no one will we sell, to no one will we deny or delay right or justice.”

Magna Carta 1215

Eleanor’s royal blood and claim to the throne meant that she was awarded no such privilege; justice and freedom were perpetually denied her. Of all the royal family and noblewomen of the time, it is Eleanor who proves that Magna Carta was not always observed and implemented, especially where women were involved, and particularly where the royal family – and the interests of the succession – were concerned.

*

Footnotes:

1David Williamson, ‘Eleanor, Princess (1184–1241)’, Brewer’s British Royalty; 2Rotuli litterarum clausarum quoted in Michael Jones, ‘Eleanor suo jure duchess of Brittany (1182×4–1241)’, Oxforddnb.com; 3Danziger, Danny and John Gillingham, 1215: The Year of Magna Carta; 4 Rotuli litterarum clausarum quoted in Michael Jones, ‘Eleanor suo jure duchess of Brittany (1182×4–1241)’, Oxforddnb.com; 5 Danziger, Danny and John Gillingham, 1215: The Year of Magna Carta

Sources:

Douglas Boyd, Eleanor, April Queen of Aquitaine; Dan Jones, The Plantagenets: the Kings who made England; Robert Bartlett, England Under the Norman and Angevin Kings 1075-1225; Alison Weir, Eleanor of Aquitaine and Britain’s Royal Families; Oxford Companion to British History; The History Today Companion to British History; Robert Lacey, Great Tales from English History; Mike Ashley, A Brief History of British Kings and Queens and The Mammoth Book of British Kings and Queens; findagrave.com; spokeo.com; Danziger, Danny and John Gillingham, 1215: The Year of Magna Carta; Michael Jones, ‘Eleanor suo jure duchess of Brittany (1182×4–1241)’, Oxforddnb.com

Pictures: Wikipedia, except Bowes Castle which is ©2020 Sharon Bennett Connolly

*

My Books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

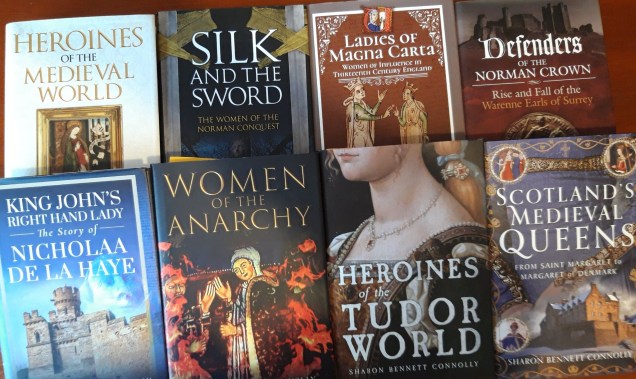

OUT NOW! Heroines of the Tudor World

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. These are the women who made a difference, who influenced countries, kings and the Reformation. In the era dominated by the Renaissance and Reformation, Heroines of the Tudor World examines the threats and challenges faced by the women of the era, and how they overcame them. From writers to regents, from nuns to queens, Heroines of the Tudor World shines the spotlight on the women helped to shape Early Modern Europe.

Heroines of the Tudor World is now available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK.

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how Empress Matilda and Matilda of Boulogne, unable to wield a sword themselves, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It shows how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other. Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon. Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org.

Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell, and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

*

Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online store.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

©2020 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS