John of Eltham was the second child and youngest son of Edward II of England and Isabella of France. He was born on 15th August 1316 at Eltham palace in Kent. Edward II had given Eltham to his queen, as a gift and she stayed there often.

John’s birth was a reassurance of the continuation of his father’s dynasty; his elder brother Edward of Windsor – the future Edward III – had been born in 1312. Although he had lost Scotland after the Battle of Bannockburn two years earlier, Edward’s throne was relatively secure when John was born. Edward II himself was not personally under pressure; as he had been when his eldest son was born.

The St Albans Chronicler reported how happy the king was, with the birth of his new son. Eubolo de Montibus was rewarded £100 for bringing the news of the birth to the king in York on 24th August. On the same day Edward II himself wrote to the Dominican friars, asking them to pray for the king, the queen, Edward of Windsor and John of Eltham, ‘especially on account of John’ who was not yet 10 days old.

Although miles away in York, Edward arranged for coverings of cloth-of-gold to be delivered for the font in Eltham’s chapel, to be used during John’s baptism. He also ordered a robe of white velvet to be made for Isabella’s churching ceremony.

Edward II also saw to the practicalities of his new son’s finances, ordering Edward of Windsor’s Justiciar in Chester, Sir Hugh Audley the Elder, to pay the rents, from the manor of Macclesfield, to the queen to cover John’s expenses. When a daughter, Eleanor of Woodstock, was born in 1318, all three children were housed together at Wallingford Castle, near Oxford.

In 1320, however, their household was rearranged again and John and Eleanor went to live with their mother, Queen Isabella, while 8-year-old Edward joined the king’s household. At the age of 6, in August 1322, John was given the Lancastrian castle of Tutbury.

Edward and Isabella’s relationship seems to have been cordial, at least, until after the birth of their last daughter, Joan of the Tower, in 1321.

Edward’s defeat of his cousin, Thomas of Lancaster, and rebel barons at the Battle of Boroughbridge in 1322 seems to have precipitated the final breakdown of the marriage. With the defeat of the rebels, Edward was able to lavish power on his favourite Hugh le Despenser the Younger.

As Despenser’s authority and influence over the king grew, Isabella’s waned. She had to turn to Hugh’s wife Eleanor, the king’s niece, as intermediary to get the king’s approval of her requests.

In 1323 and 1324 Isabella spent a lot of time in London, seeing a great deal of her children, including John. In September 1324 John and his sister, Eleanor, were placed in the care of Eleanor Despenser.

In 1325 Queen Isabella was sent to France to negotiate peace with her brother, King Charles IV. John and his sisters remained in England, but Isabella managed to persuade Edward II to send his son Edward of Windsor, newly created Duke of Gascony, to France to do homage for his French lands. With the heir in her custody Isabella and her ally, Roger Mortimer, planned their return to England.

On Mortimer’s invasion in 1326 there was anarchy in London. The mob broke into the Tower of London, intending to set up 9-year-old John of Eltham as ruler of the city. However, Edward II was soon captured and in January 1327 he was forced to abdicate in favour of his eldest son, 14-year-old Edward III.

Edward II was probably murdered at Berkeley castle in September 1327, although some historians now argue he escaped and lived on the Continent as a hermit, under papal protection.

Although Edward was now king, Roger Mortimer was de facto ruler of England. John was a natural ally to his brother against the growing oppression of Mortimer. When Mortimer demanded he receive the Earldom of March at the forthcoming Salisbury Parliament, Edward countered by insisting his brother be given a rich earldom. And in October 1328, on the last day of parliament, John was created Earl of Cornwall.

From May to June of 1329 John was appointed Guardian of the Realm while Edward III travelled to France to pay homage for his French possessions; he was briefly appointed Guardian again in April 1331 when Edward went on pilgrimage to northern France.

Married to Philippa of Hainault, with a son, Edward, in the cradle; in October 1330 Edward III had managed to overthrow the hated Mortimer and began his personal rule. In the lead up to the coup John must have been with his brother almost constantly; he witnessed 66 charters between January and October 1330, 10 more than Mortimer himself.

Edward was very fond of his brother. They had shared the terror of Mortimer’s dictatorship. John had benefited from the flood of estates and rewards following Mortimer’s downfall; Edward had been too cautious to distribute such largesse to his non-royal friends.

While their sisters married – Joan to David of Scotland and Eleanor to the Count of Guelders – John remained very much a stalwart of Edward’s lavish court. A writ in March 1334, for clothing for the court, has John sharing the costs of pearls used to decorate seven hoods; while Edward footed the bill for two of the hoods, John financed five of them.

Several brides were proposed for him; Jeanne, a daughter of the Count of Eu, Mary of Blois and Mary of Coucy among them. In October 1334 John received a papal dispensation to marry Maria, a daughter of Fernando IV, king of Castile and Leon. However, the marriage never took place.

When Edward turned his attentions to Scotland, John was with him. Edward III supported the claims of Edward Balliol, against David II Bruce, his sister’s husband, for the Scots crown. David’s forces were defeated at the Battle of Halidon Hill. While Edward III commanded the central division the king’s uncle, the Earl of Norfolk, led the right with Prince john by his side. Hand-to-hand combat followed a terrifying onslaught of arrows, and the Scots were routed.

John was also by his brother’s side during the 1335 and 1336 campaigns in Scotland. In June 1335 John joined the muster at Newcastle. The 1335 war was without compromise: the army undertook a campaign of looting, raping, killing and burning.

John appears to have been a competent and ruthless commander. Trusted by his brother he commanded a force in southern Scotland, putting down opposition to Edward Balliol. It is said that Joh burned down Lesmahagow Abbey when it was filled with people who had sought sanctuary from the English troops.

In 1336 John led a great council in Northampton while his brother was still in Scotland. The council decided to send an embassy to France to seek a compromise over the developing hostilities (France were promising to aid the Scots). John was soon back with Edward III in Perth where he died on 13th September 1336, just a month after his 20th birthday.

Thomas Gray, writing in 1355, said John died a ‘good death’, it is thought he died of a fever, brought on by his military exertions. There were, however, rumours of foul play and the Scots even suggested John was stabbed by an enraged Edward at the altar of the Church of St John, angry at his brother’s ruthlessness against the Scots.

Edward III was very upset by John’s death. He ordered 900 masses to be said for his brother’s soul, and even a year later his accountant noted extra alms-giving by the king in john’s memory.

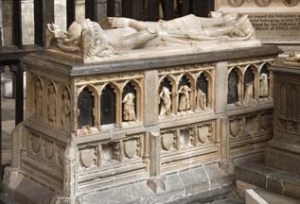

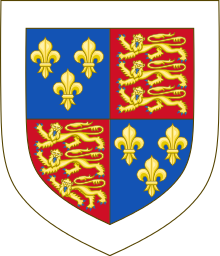

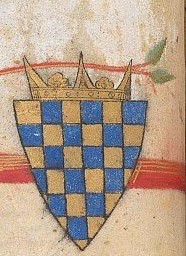

John was buried in Westminster Abbey on 13th January 1337 and Edward III had an alabaster monument erected in St Edmund’s Chapel. The effigy has a moustache and is wearing a mixture of mail and plate armour, with John’s coat of arms on the shield. The Weepers surround the base of the tomb and could be representative of John’s family members.

*

Photographs: The Weepers © the V&A Museum, London; Tomb of Prince John of Eltham © Westminster Abbey; all other pictures courtesy of Wikipedia

*

Sources: The Perfect King, the Life of Edward III by Ian Mortimer; The Life and Time of Edward III by Paul Johnson; The Reign of Edward III by WM Ormrod; The Mammoth Book of British kings & Queens by Mike Ashley; Britain’s’ Royal Families, the Complete Genealogy by Alison Weir; Brewer’s British Royalty by David Williamson; The Plantagenets, the Kings Who Made Britain by Dan Jones; edwardthesecond.blogspot.co.uk; westminster-abbey.org.

*

My books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online store.

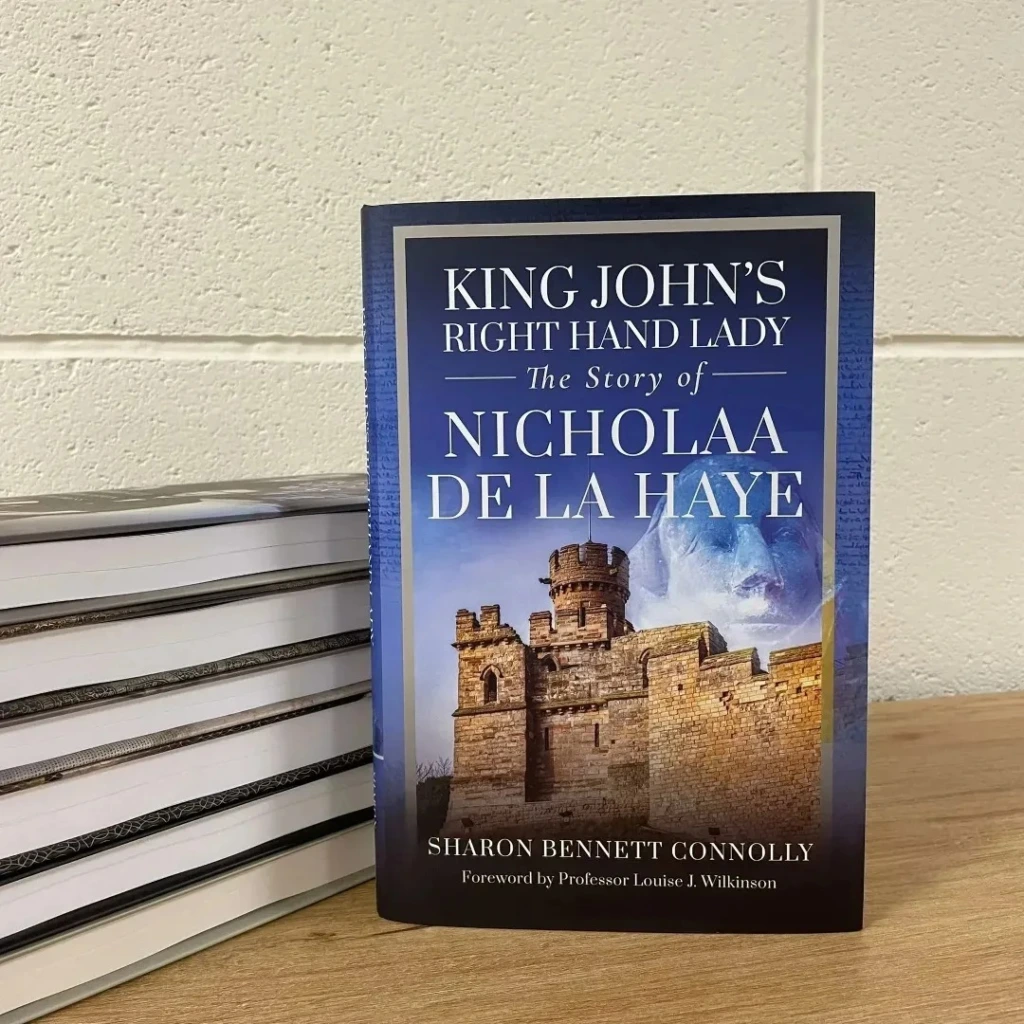

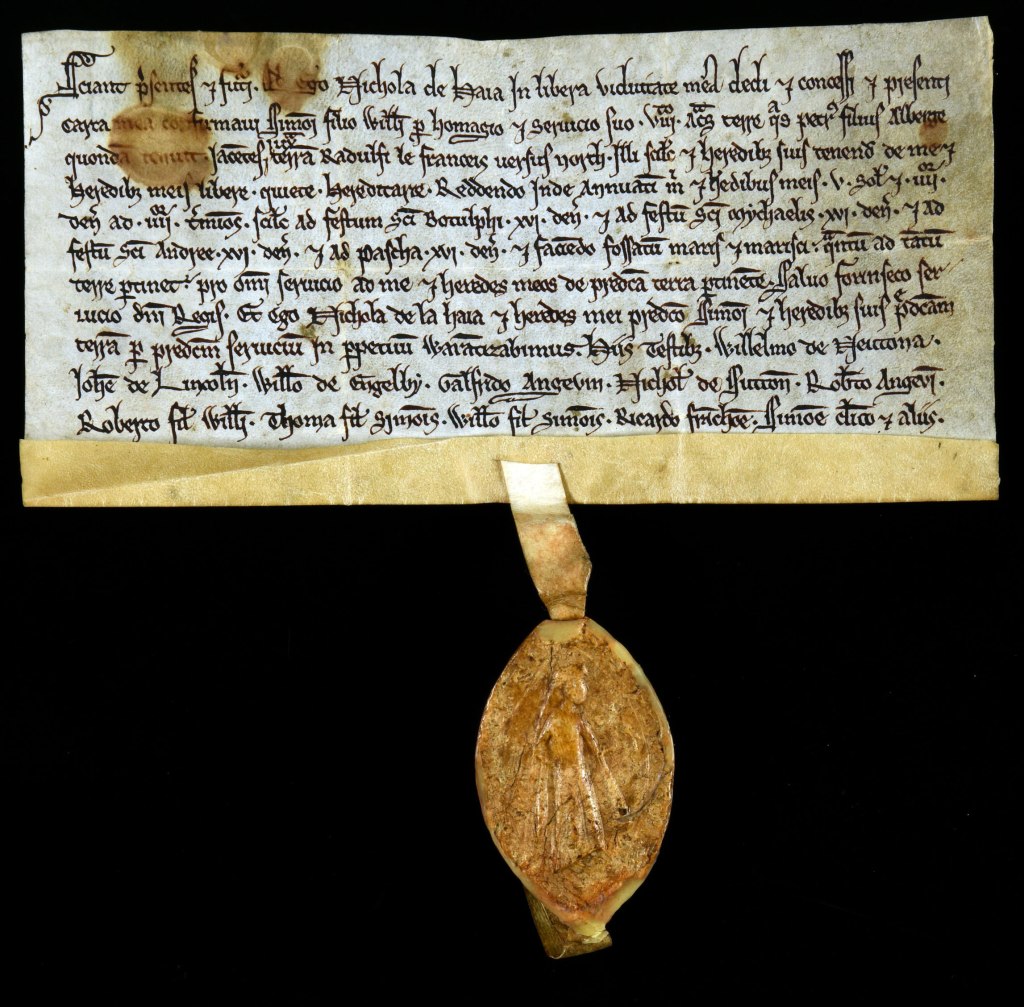

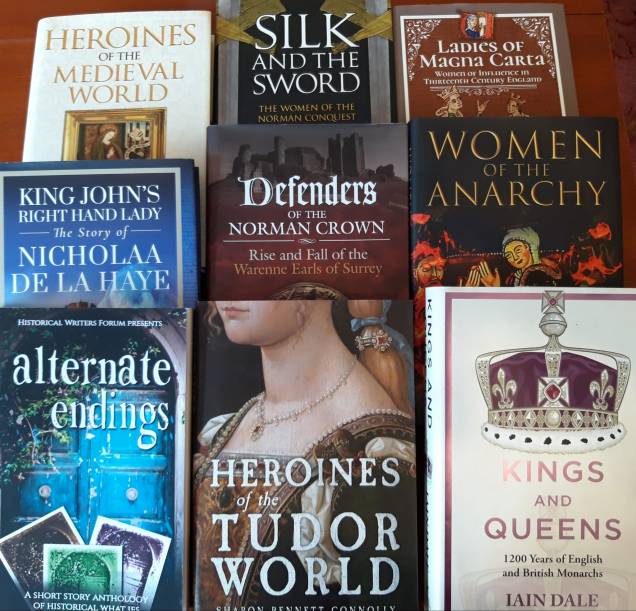

Out now: King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye

In a time when men fought and women stayed home, Nicholaa de la Haye held Lincoln Castle against all-comers, gaining prominence in the First Baron’s War, the civil war that followed the sealing of Magna Carta in 1215. A truly remarkable lady, Nicholaa was the first woman to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Her strength and tenacity saved England at one of the lowest points in its history. Nicholaa de la Haye is one woman in English history whose story needs to be told…

King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is now available from Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

Coming 15 January 2024: Women of the Anarchy

On the one side is Empress Matilda, or Maud. The sole surviving legitimate child of Henry I, she is fighting for her birthright and that of her children. On the other side is her cousin, Queen Matilda, supporting her husband, King Stephen, and fighting to see her own son inherit the English crown. Both women are granddaughters of St Margaret, Queen of Scotland and descendants of Alfred the Great of Wessex. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how these women, unable to wield a sword, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It show how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other.

Available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK.

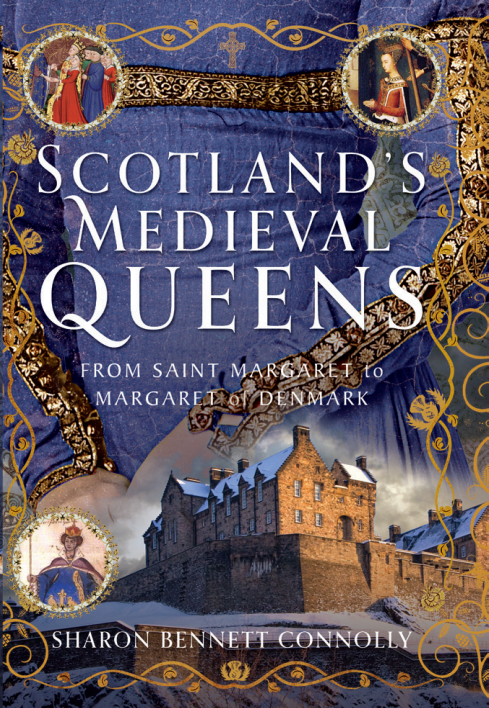

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, of the successes and failures of one of the most powerful families in England, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Defenders of the Norman Crown: Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey is now available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org.

Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org.

Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org.

Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell, and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

*

Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online store.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

*

©2015 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS