Today, it is a pleasure to be chatting with my good friend Charlene Newcomb, just as her latest book, Rogues and Kings hits the shops. Rogues and Kings is a fabulous story, set in 1216, featuring Robin Hood and his gang/friends, King John and the magnificent Nicholaa de la Haye. I highly recommend it and will be writing a review shortly.

But first, Char, let’s have a chat.

Sharon: We’re here today talking medieval historical fiction, but I know you started your publishing career with short stories in the Star Wars universe. How did that come about?

Charlene: Timothy Zahn’s Heir to the Empire, a sequel to the movie Return of the Jedi, inspired me to write my own Star Wars sequel though my writing credentials as of 1993 consisted of an alternative history short story in high school and a few scenes from other attempts at creativity. I was a huge fan of the original Star Wars trilogy. (Shouldn’t that count for something?) I quickly discovered only well known authors were being invited to publish in that universe but ran across a call for short stories in an official Lucasfilm licensed role-playing game magazine. My novel had broken all the rules for submission, but I took one of my original characters—a rebel underground freedom fighter named Alexandra Winger—and created her backstory. “A Glimmer of Hope” was accepted, vetted through West End Games and Lucasfilm, and illustrated and published in the Star Wars Adventure Journal (SWAJ). Alex even has a Wookiepedia entry!

Sharon: How did you get from Star Wars to medieval historical fiction?

Charlene: The publisher of the SWAJ declared bankruptcy so the timing of that—around 1998—along with single parenthood and a demanding career interrupted my writing journey. Several years later a BBC Robin Hood series stirred my interest in Richard the Lionheart and the Third Crusade. Down the research rabbit hole I went, and my itch to create an original novel-length story surfaced.

I wanted to see the Lionheart through the eyes of the men who served him so I created two original characters: the battle-hardened Stephan l’Aigle and the naive and inexperienced Henry de Grey. Men of the Cross (Battle Scars I) takes the young knights to the Holy Land and then back to England. I introduced some secondary characters in that novel: two teenaged camp followers and a knight named Will who was an expert with bow and had been in love with, and left behind, a girl named Marian. My critique partners could tell I was hinting at a Robin-Hood-type character in Will—they convinced me I should give readers a reimagining of the origins of the legend. Will became Robin and the two teenagers became my Allan a Dale and Little John.

Sharon: Tell us about your books.

The Battle Scars series (3 books) cover events of King Richard I’s reign from 1190-1199: the Third Crusade, Prince John’s attempted coup, and King Richard’s war against Philip of France for his continental holdings. The series ends shortly after Richard’s death in 1199.

The two books In Tales of Robin Hood can be read as stand-alones though they are closely tied. Both Tales take place in 1216 with the premise that Allan a Dale leads ‘the Hood’ in Sherwood Forest and Robin, in his fifties, has assumed a different identity and been in self-exile to finally have a life with Marian in Yorkshire. King John has never forgotten their roles in thwarting his attempt to overthrow Richard. He would hang them all in his thirst for revenge.

Sharon: What attracts you to the 12th-13th centuries?

Empress Matilda, Eleanor of Aquitaine, Henry II, Richard I, John—such rich (and not always so pretty) lives with powerful stories in incredible times: the Anarchy, Thomas Becket’s murder, the Crusades, the rise and fall of the Angevin Empire, Magna Carta. Unlike most school kids, I was a history nerd and soaked it in when Dad made an effort to stop at historic U.S. sites every time we traveled. But the medieval period was an era barely touched on in the world history classes I was required to take.

I loved the idea of Robin Hood as a close companion and loyal knight of Richard I, accompanying the king to the Holy Land, and then later serving as a spy in Prince John’s mesnie. When Richard, John, and their mother Eleanor of Aquitaine are on the page, the actual history at times almost feels like fiction—the dysfunctional family, sons (and wife) in rebellion against Henry II, brother against brother, scheming enemies, a paranoid, distrustful king. To weave Robin, Allan, Little John, and the other Hood (including Henry and Stephan) into that history lets me reveal lines between traitors and heroes.S

Sharon: What don’t people know about Robin Hood?

Charlene: Modern audiences are familiar with the original legend through movies and television, most of which take place in the late 12th/early 13th century. But many don’t realize there is no evidence to indicate Robin was an actual historical figure. The first written stories about him appear mid-15th century though oral stories were passed around in the latter half of the 1400s. Television and movies generally portray Robin as serving King Richard I and/or fighting against King John (1189-1216), but the oldest ballads don’t name either of them. The Gest of Robyn Hode (late 1400s) notes Robin’s meeting with ‘Edwarde, our comly kynge,’ referring, many believe, to Edward I, II, or III, whose reigns covered the years from 1272-1377.

Sharon: How do you approach researching your topic?

Pre-14th century history is challenging for the historical fiction writer. Primary sources such as official documents and contemporary chronicles were written in medieval Latin. Fortunately, many of them have been translated and some are available freely online or are discussed by historians in works about the people and events of the era. When my university library didn’t have what I needed, I turned to interlibrary loan. (Thank you, libraries!) Footnotes and bibliographies in these resources provided more threads to follow.

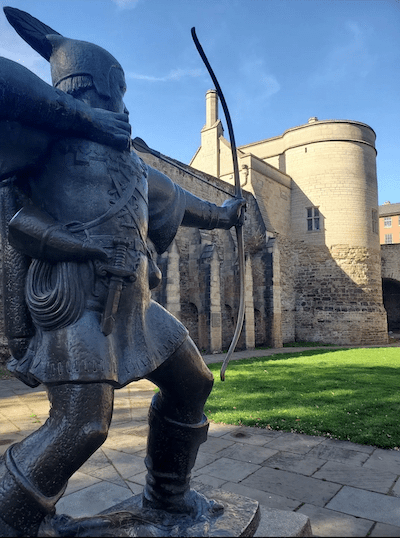

Visiting the places I write about, standing in awe of the Major Oak in Sherwood, walking around the baileys and along the battlements of castles, even seeing the ruins, is inspiring, a blast. Castles and towns like Lincoln, Nottingham, York, and Newark have changed considerably in 800 years which meant more research to get everyday life and the settings right. I’d go back again and again if I lived closer. I will never forget meeting up with writer friends like you, and comparing notes on the history of a place.

Sharon: What are you working on now?

Charlene: I am gathering notes and considering story arcs surrounding two different events that I’d like to feature in short stories: King John’s rescue of his mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, at the siege of Mirebeau in 1202; and the Battle of Lincoln Fair in 1217. (Sharon: I definitely think you should do one on the Battle of Lincoln Fair. I can just imagine Robin and his friends helping Nicholaa out there!)

Sharon: And finally, what is the best thing about being a writer?

Writing can be a solitary undertaking so hearing from readers and friends that you’ve crafted a story and characters they tell you they love is such a rush. Just as rewarding is when you write ‘the end’ on something that started with a single idea, such as what might be the consequences if the son of Robin Hood served in King John’s household, write down a half dozen bullet points that spawn many more, and suddenly (or rather over the course of many, many months) the pieces gel and become chapters in a tome of nearly 400 pages. What is surprising is when a character takes over the story and blurts out something you weren’t expecting. Your jaw drops and then you sit back and realize, wow, that opens up a whole new dilemma. Run with it! Hopefully the reader experiences that same feeling.

About the Author:

Charlene Newcomb, aka Char, is a retired librarian, a U.S. Navy veteran, mom to 3 amazing humans, and grandma to 3. She writes historical fiction and science fiction. Her award-winning Battle Scars trilogy is set in the 12th century during the reign of Richard the Lionheart. Her writing roots are in science fiction: in the Star Wars Expanded Universe (aka Legends) where she published 10 short stories in the Star Wars Adventure Journal, and an original novel, Echoes of the Storm. Char returned to medieval times with Rogue and her latest novel Rogues & Kings, both in her Tales of Robin Hood series.

Website: https://charlenenewcomb.com Newsletter: https://charlenenewcomb.substack.com/ Facebook: https://facebook.com/CharleneNewcombAuthor Instagram: https://instagram.com/charnewc Bluesky: https://charnewcomb.bsky.social/ Pinterest: https://www.pinterest.com/charnewcomb/

About Rogues and Kings

Deadly secrets. Hidden identities. A true enemy.

Silence is the only shield.

The year is 1216 and civil war rages in England. King John ravages the countryside against rebellious barons and a French invasion. Unbeknownst to him, his newest squire, Richard, is in fact the son of a man the king would hang without a second thought. A man the common folk call Robin Hood.

For years, Robin has lived as a knight in exile. But when his son is ensnared in the treachery of the royal court, Robin is forced out of the shadows, aided by his outlaw friends in the Hood.

There is no question for Richard where his loyalties lie but it’s more than his own life at risk. He has the trust of a dangerous king. Can he serve the Hood better from within John’s inner circle, or will schemes against the crown unravel?

Rob from the rich, give to the poor takes on a whole new meaning.

Rogues & Kings is a sweeping tale of courage and betrayal in a kingdom on the edge of ruin, of a boy coming of age in the midst of war, and of legends being born.

Images courtesy and ©2026 of Charlene Newcomb

*

My Books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop. or by contacting me.

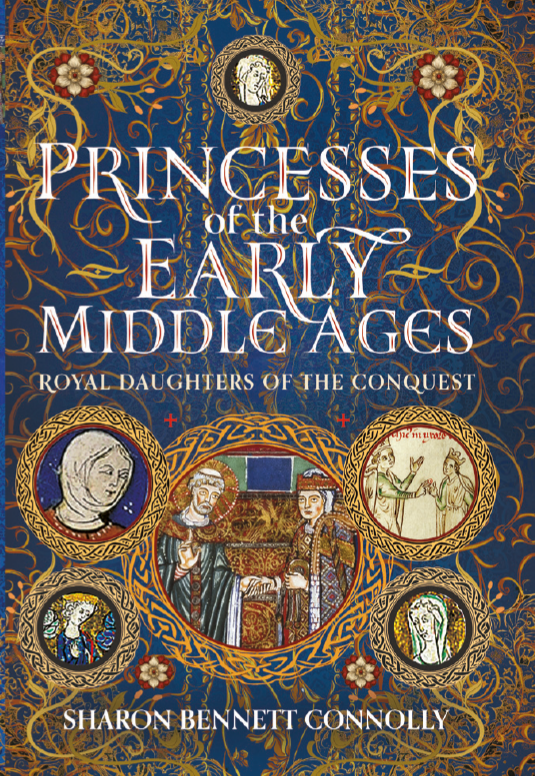

Coming 30 March: Princesses of the Early Middle Ages

Daughters of kings were often used to seal treaty alliances and forge peace with England’s enemies. Princesses of the Early Middle Ages: Royal Daughters of the Conquest explores the lives of these young women, how they followed the stereotype, and how they sometimes managed to escape it. It will look at the world they lived in, and how their lives and marriages were affected by political necessity and the events of the time. Princesses of the Early Middle Ages will also examine how these girls, who were often political pawns, were able to control their own lives and fates. Whilst they were expected to obey their parents in their marriage choices, several princesses were able to exert their own influence on these choices, with some outright refusing the husbands offered to them.

Their stories are touching, inspiring and, at times, heartbreaking.

Princesses of the Early Middle Ages: Royal Daughters of the Conquest is now available for pre-order from Pen & Sword and Amazon.

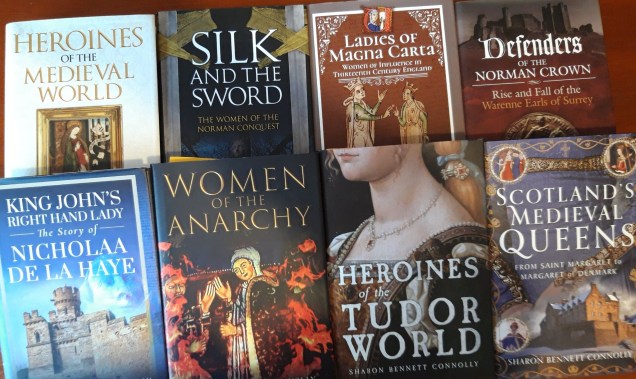

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Scotland’s history is dramatic, violent and bloody and Scotland’s Medieval Queens have seen it all. This is the story of Scotland through their eyes. Available now from Amazon and Pen and Sword Books. Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. Heroines of the Tudor World is now available from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how Empress Matilda and Matilda of Boulogne, unable to wield a sword themselves, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It shows how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other. Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org. Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

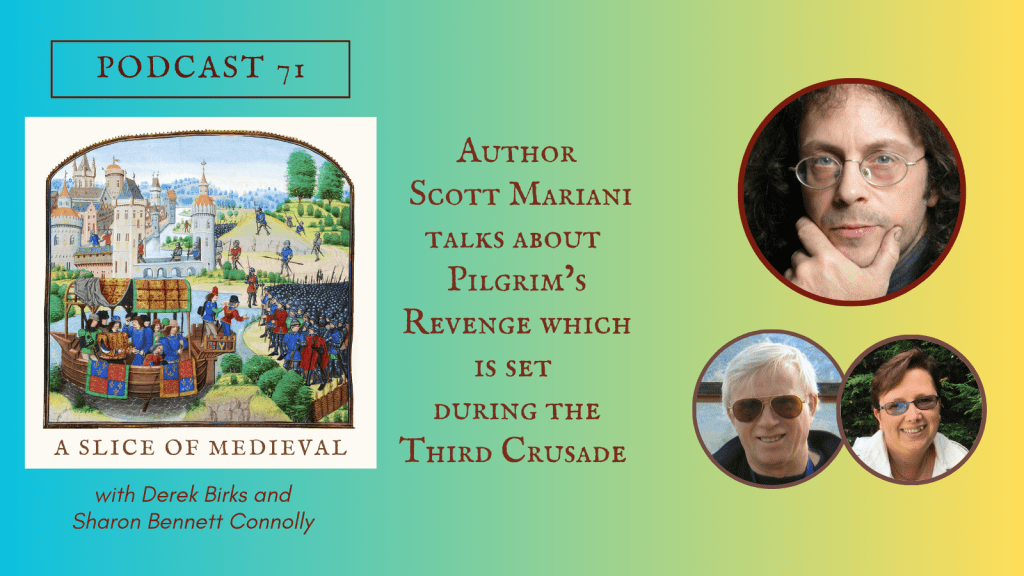

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Ian Mortimer, Bernard Cornwell, Elizabeth Chadwick and Scott Mariani, and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

Every episode is also now available on YouTube.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter, Threads, Bluesky and Instagram.

*

©2026 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS and Charlene Newcomb