Saturday 20th May, 2017, marked the 800th anniversary of one of Medieval England’s most decisive battles. The Second Battle of Lincoln, also known as “The Lincoln Fair”, rescued England from the clutches of Louis, Dauphin of France and future King Louis VIII.

England had been in turmoil during the last years of the reign of King John, with the barons trying to curtail the worst of his excesses. It had been hoped that the 1215 issuing of Magna Carta would prevent war, but when John reneged on the Great Charter, war was inevitable. England’s disgruntled barons even went so far as to write to Philip II, King of France, and invite his son, Louis, to come and claim the throne. Louis jumped at the chance and landed on England’s shores in 1216.

Strategically placed in the centre of the country, Lincoln was a target for the rebel barons and their French allies. An important Royalist stronghold, it was held by the redoubtable hereditary castellan, Lady Nicholaa de la Haye, who had been widowed in the early months of 1215. Lincoln Castle had already been under siege in 1216, when the northern rebels had been paid to go away. The rebels – including the King of Scotland – then fled north as John’s army advanced on the city. It was probably after the 1216 siege that Nicholaa made a show of relinquishing her post as castellan; however, John had other ideas:

And once it happened that after the war King John came to Lincoln and the said Lady Nicholaa went out of the eastern gate of the castle carrying the keys of the castle in her hand and met the king and offered the keys to him as her lord and said she was a woman of great age and was unable to bear such fatigue any longer and he besought her saying, “My beloved Nicholaa, I will that you keep the castle as hitherto until I shall order otherwise”.¹

John went even further to show his trust in Nicholaa, who was a long-time supporter of the unpopular king. As Louis consolidated his position in the south, John made an inspection of Lincoln castle in September 1216. He then moved south, losing his baggage as he crossed the Wash and falling ill as he travelled. After a brief stay at Swineshead Abbey, he made his way to Newark, where he died on the night of 18/19 October. Mere hours earlier, John had made history by appointing Nicholaa to the post of Sheriff of Lincolnshire. She was the first woman to ever be appointed sheriff in her own right. .

When John died, half of his country was occupied by a foreign invader and his throne now occupied by his 9-year-old son, Henry III. The only royal castles still in royalist hands were Windsor, Dover – and Lincoln. The elder statesman and notable soldier William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke was appointed Regent and set out to save the kingdom.

Following the coronation of young Henry, Magna Carta was reissued and some of the rebel barons returned to the fold, not wanting to make war on a 9-year-old king. However, Louis still had powerful supporters and did not seem keen to give up on his dream to rule England.

Louis’ forces, under the Comte de Perche, along with leading rebels Saher de Quincy, Earl of Wonchester, and Robert FitzWalter, marched north intending to relieve Mountsorel Castle, which was being besieged by the Earl of Chester. Fearing he was facing the entire French invading force, Chester had withdrawn as the French arrived and Perche’s forces diverted to Lincoln. Gilbert de Gant, on hearing news of John’s death, had occupied the city in late 1216 with a small force. He was now reinforced by Perche’s army and in early 1217, they laid siege to the castle. Now in her 60s, Nicholaa de la Haye took charge of the defences, with the help of her lieutenant, Sir Geoffrey de Serland.

For almost 3 months – from March to mid-May – siege machinery continuously bombarded the south and east walls of the castle. When the allied force proved insufficient to force a surrender, the French had to send for reinforcements. This meant that half of Louis’ entire army was now outside the gates of Lincoln Castle and provided William Marshal with an opportunity; one decisive battle against Louis’ forces at Lincoln could destroy the hopes of Louis and the rebel barons, once and for all.

Risking all on one battle was a gamble, but one that Marshal was determined to take. Spurred on by the chivalrous need to rescue a lady in distress – the formidable Lady Nicholaa – Marshal ordered his forces to muster at Newark by 17th May. While the young king, Henry III, waited at Nottingham, Marshal’s army prepared for war. The papal legate, Guala Bicchieri, absolved the Royalist army of all their sins – of all the sins they had committed since their birth – and excommunicated the French and rebel forces, before riding to join the king at Nottingham.

While at Newark, Marshal set out the order of battle, although not without some argument. The Norman contingent and Ranulf, earl of Chester, both claimed the right to lead the vanguard. However, when Ranulf threatened to withdraw his men, it was decided to acquiesce to his demands.

Lincoln is an unusual city; its castle and cathedral sit at the top of a hill, with the rest of the city to the south, at the hill’s base. In the 12th century it was enclosed in a rectangular wall, which had stood since Roman times, with 5 gates, and the castle abutting the wall at the north-west corner. William Marshal decided not to attack Lincoln from the south, which would have meant heading up the Fosse Way (the old Roman road) and forcing a crossing of the River Witham, before climbing the steep slope to the castle and cathedral (so steep, the road going up is called Steep Hill to this day). Instead he chose to take a circuitous route, so he could come at the city from the north-west and attack close to the castle and cathedral, directly where the enemy troops were concentrated.

On the 19th May Marshal’s forces rode from Newark alongside the the River Trent and set up camp at Torksey, about 8 miles to the north of Lincoln, or Stow, depending on the source you read. Or, perhaps, both.

The English commanders included William Marshal, earl of Pembroke, his son, Young William Marshal, and nephew, John Marshal, in addition to Ranulf, Earl of Chester, William Longspée, Earl of Salisbury, Peter des Roches, Bishop of Winchester, and Faulkes de Breauté, King John’s mercenary captain. They led 406 knights, 317 crossbowmen and a large number of sergeants-at-arms, foot soldiers and camp followers.

Although Louis was in charge of the French forces in England, those in Lincoln were led by Thomas, Comte de Perche, himself a grandson of Henry II’s daughter Matilda, and therefore a cousin of King Henry III. Perche was also related to William Marshal; both were descended from sisters of Patrick, 1st earl of Salisbury. The commanders of the English rebels in the city included Robert FitzWalter and Saer de Quincey, Earl of Winchester. They led over 600 knights and several thousand infantry.

At various points in the lead up to the battle, William Marshal is known to have made some stirring speeches. When battle was imminent, he made one more;

Now listen, my lords! There is honour and glory to be won here, and I know that here we have the chance to free our land. It is true that you can win this battle. Our lands and our possessions those men have taken and seized by force. Shame be upon the man who does not strive, this very day, to put up a challenge, and may the Lord our God decide the matter. You see them here in your power. So much do I fully guarantee, that they are ours for the taking, whatever happens. If courage and bravery are not found wanting.

And, if we die …, God, who knows who are his loyal servants, will place us today in paradise, of that I am completely certain. And, if we beat them, it is no lie to say that we will have won eternal glory for the rest of our lives and for our kin. And I shall tell you another fact which works very badly against them: they are excommunicated and for that reason all the more trapped. I can tell you that they will come to a sticky end as they descend into hell. There you see men who have started a war on God and the Holy Church. I can fully guarantee you this, that God has surrendered them into our hands.

Let us make haste and attack them, for it is truly time to do so!²

As with all battles, the information gets confusing as the fighting commences, timings get distorted and facts mixed. No two sources give exactly the same information. So the story of a battle is a matter of putting the pieces together and making sense of various snippets of information – much as it would have been for the commanders on the day.

In the dawn of 20th May the English Royalist army marched south towards Lincoln, probably climbing to the ridge at Stow so as not to have that climb nearer to Lincoln, with the enemy in sight. Marshal had hoped that, on reaching the plain in front of the city walls, the French and rebels would come out and meet him and a pitched battle would be fought outside of the city. Marshal was resting everything – the very future of England – on the outcome of that one battle. However, it seems that, although the allied leaders did come out and take a look at the forces arrayed before them, they then chose to stay inside the city walls and wait for the Royalists to come to them.

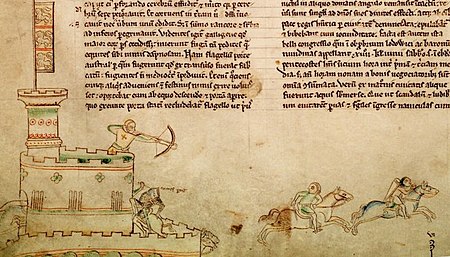

William Marshal’s nephew, John Marshal was sent to the castle, to ascertain the situation within the city, but as he approached, Nicholaa’s deputy, Geoffrey de Serland, was making his way out to report to the English commanders that the castle was still in Nicholaa’s hands. It is not hard to imagine Nicholaa or her deputy climbing the tallest towers of the castle – perhaps the one now known as the Observatory Tower, used in Matthew Paris’s illustration – to watch out for an approaching relief force. Seeing the Marshal’s banners appearing in the north must have been an amazing feeling.

The castle itself had two main gates, one in the eastern wall and one in the west, with postern gates in the Lucy Tower to the south-east of the castle, the tower known as Cobb Hall to the north-east corner and another in the northern wall. On ascertaining that the castle still held, Peter des Roches then made his way inside, most likely by either the postern gate in Cobb Hall, or the one in the northern wall. Having met with Nicholaa de la Haye in the Lucy Tower, it seems he then made his way into the town via its postern gate, to check the defences and try to find a way into the city.

According to the Histoire, des Roches’ reconnaissance proved successful and he reported to Marshal that there was a gate within the north-west wall of the city, which, although blockaded, could be cleared. As Marshal set men to clearing the blockaded gate, the earl of Chester was sent to attack the North Gate as a diversion and Faulkes de Breauté took his crossbowmen into the castle via a postern gate and set them on the ramparts above the East Gate, so their bolts could fire down on the besiegers.

De Breauté fell into disgrace in 1224 and so the major source for the Battle of Lincoln – the Histoire de Guillaume le Maréschale – plays down his role in the battle. However, his crossbowmen managed to keep the French forces focussed on the castle, rather than Marshal’s forces outside the city. De Breauté did make a sortie out of the East Gate, to attack the besiegers, but was taken prisoner and had to be rescued by his own men; although at what stage of the battle this happened is uncertain.

The Histoire tells how it took several hours, it seems, for Marshal’s men to break through the gate. The 70-year-old William Marshal was so eager to lead the charge that he had to be reminded to don his helmet. Once safely helmeted, he led his men through the city gates and down Bailgate to approach the castle from the north, his men spilling into the space between castle and cathedral, where the main force of the besiegers were still firing missiles at the castle.

The English forces took the enemy so totally by surprise that one man – according to the Histoire he was the enemy’s ‘most expert stonethrower’² – thought they were allies and continued loading the siege machinery, only to have his head struck from his shoulders.

Almost simultaneously, it seems, the earl of Chester had broken through a gate to the northeast and arrived from behind the cathedral. Battle was joined on all sides. Vicious, close-quarter combat had erupted in the narrow streets, but the fiercest fighting was in front of the cathedral. In the midst of the melee, William Longspée took a blow from Robert of Roppesley, whose lance broke against the earl. The aged Marshal dealt a blow to Roppesley that the knight who, having crawled to a nearby house ‘out of fear, [he] went to hide in an upper room as quickly as he could’.³

The Comte de Perche made his stand in front of the cathedral, rallying his troops; and it was there he took a blow from Reginald Croc which breached the eye slit of his helmet. Croc himself was badly wounded and died the same day. The Comte continued to fight, striking several blows to the Marshal’s helmet (the one he had almost forgotten to don), before falling from his horse. It was thought the Comte was merely stunned until someone tried to remove his helmet and it was discovered that the point of Croc’s sword had pierced the count’s eye and continued into his brain, killing him.

With the death of their leader, the French and rebel barons lost heart and started pulling back. They fled downhill, to the south of the city. Although they briefly rallied, making an uphill assault, the battle was lost. There was a bottleneck as the defeated soldiers tried to escape through the city gates, made worse by a cow stuck in the South Gate and the bridge across the Witham as the enemy forces fled. The cow could not be moved and so the rebels butchered it – only to discover a dead cow was even harder to move. The rebel leaders, Saher de Quincey and Robert FitzWalter were both taken prisoner, as were many others. In total, about half of the enemy knights surrendered.

The battle had lasted no more than 6 hours.

Sadly, in the aftermath of the battle, women took to the river with their children, in small boats, to escape the unwanted attentions of the victorious army. However, not knowing how to control the overloaded craft, many capsized and the women and children drowned.

The city, which had supported the rebels, was sacked, churches included; the excommunication seen as permission that everything was fair game. Although, one does wonder how much choice the citizens had in siding with the rebels and their French allies – survive or die would have been the reality. The battle earned the name ‘The Lincoln Fair,’ possibly because of the amount of plunder gained by the victorious English army.

Immediately the battle was won, William Marshal, earl of Pembroke, rode to Nottingham to inform the king of the victory. The Battle of Lincoln turned the tide of the war. On hearing of the battle, Louis immediately lifted his siege of Dover Castle and withdrew to London. His situation became desperate, his English allies were bristling against the idea of Louis giving English land as reward to his French commanders and were beginning to see the young Henry III as rightful king – after all, the son couldn’t be blamed for the actions of the father. In August of the same year Louis was soundly defeated at sea in the Battle of Sandwich, off the Kent coast. By September he had sued for peace and returned to France.

In an incredible demonstration of ingratitude, within 4 days of the relief of the Castle, Nicholaa de la Haye’s position of Sheriff of Lincolnshire was given to the king’s uncle William Longspée, Earl of Salisbury, who took control of the city and seized the castle. Salisbury was the father-in-law of Nicholaa’s granddaughter – and heir – Idonea de Camville. However, not one to give up easily, Nicholaa travelled to court to remind the king’s regents of her services, and request her rights be restored to her. A compromise was eventually reached whereby Salisbury remained as Sheriff of the County, while Nicholaa held the city and the castle. Although Salisbury never gave hope of acquiring the castle, it was still in Nicholaa’s hands when he died in 1226.

The battle had been a magnificent victory for the 70-year-old regent, William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke, and is a testament to his claim to the title ‘The Greatest Knight’. He staked the fate of the country on this one battle and pulled off a decisive victory, saving his king and country. Although, he could not have achieved it, had Nicholaa not so stubbornly held onto Lincoln Castle.

*

Footnotes: ¹Irene Gladwin: The Sheriff; The Man and His Office; ²Histoire de Guillaume le Maréschal translated by Stewart Gregory; ³ Quoted in Thomas Asbridge’s The greatest Knight

All photos from Lincoln – Castle, Cathedral, Nicholaa de la Haye and Magna Carta, © Sharon Bennett Connolly 2015. All other pictures are courtesy of Wikipedia.

*

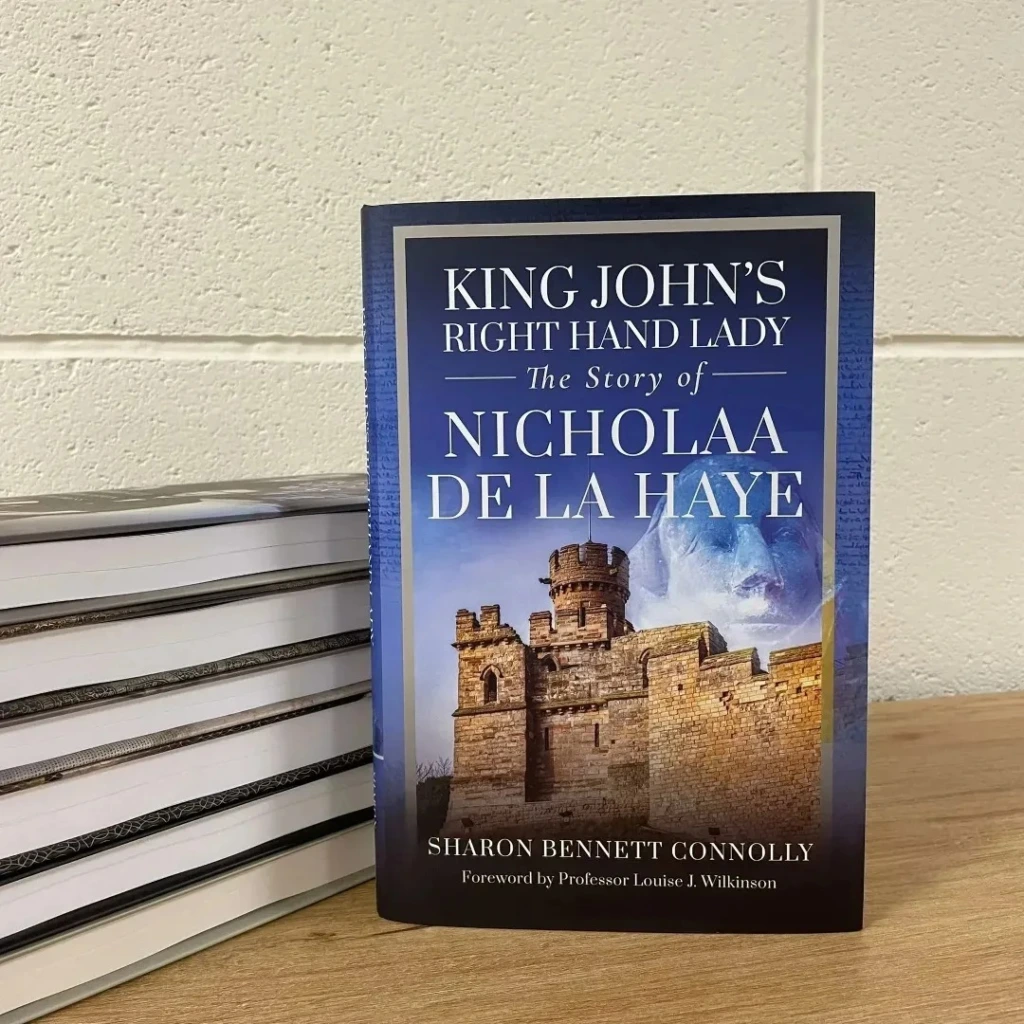

You can read more on the story of the 1217 Battle of Lincoln – and Nicholaa de la Haye in particular – in my book, King John’s Right Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye. Or listen to the episode on Nicholaa de la Haye in our A Slice of Medieval podcast

*

Sources: King John by Marc Morris; Henry III The Son of Magna Carta by Matthew Lewis; The Demon’s Brood by Desmond Seward; The Greatest Knight by Thomas Asbridge; The Knight Who Saved England by Richard Brooks; The Plantagenet Chronicles edited by Elizabeth Hallam; Brassey’s Battles by John Laffin; 1215 The Year of Magna Carta by Danny Danziger & John Gillingham; The Life and times of King John by Maurice Ashley; The Story of Britain by Roy Strong; The Plantagenets, the Kings Who Made England by Dan Jones; England Under the Norman and Angevin Kings by Robert Bartlett; lincolnshirelife.co.uk; catherinehanley.co.uk; magnacarta800th.com; lothene.org; lincolncastle.com; Nick Buckingham; The Sheriff: The Man and His Office by Irene Gladwin; Elizabeth Chadwick; swaton.org.uk; Histoire de Guillaume le Mareschal translated by Stewart Gregory, usna.edu.

*

My Books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

Out now: Scotland’s Medieval Queens

Scotland’s history is dramatic, violent and bloody. Being England’s northern neighbour has never been easy. Scotland’s queens have had to deal with war, murder, imprisonment, political rivalries and open betrayal. They have loved and lost, raised kings and queens, ruled and died for Scotland. From St Margaret, who became one of the patron saints of Scotland, to Elizabeth de Burgh and the dramatic story of the Scottish Wars of Independence, to the love story and tragedy of Joan Beaufort, to Margaret of Denmark and the dawn of the Renaissance, Scotland’s Medieval Queens have seen it all. This is the story of Scotland through their eyes.

‘Scotland’s Medieval Queens gives a thorough grounding in the history of the women who ruled Scotland at the side of its kings, often in the shadows, but just as interesting in their lives beyond the spotlight. It’s not a subject that has been widely covered, and Sharon is a pioneer in bringing that information into accessible history.’ Elizabeth Chadwick (New York Times bestselling author)

Available now from Amazon and Pen and Sword Books

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. Heroines of the Tudor World is now available from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how Empress Matilda and Matilda of Boulogne, unable to wield a sword themselves, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It shows how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other. Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org. Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell and Michael Jecks, and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved. Every episode is also now available on YouTube.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter, Threads, Bluesky and Instagram.

©2017 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS