For my latest edition of Wordly Women, it is an absolute pleasure to welcome my dear friend, Anna Belfrage. Anna writes both historical fiction and time slip and is a magician with the written word. Her Castilian Saga books are something special and I loved the King’s Greatest Enemy books!

So, welcome Anna!

Sharon: What got you into writing?

Anna: I think many writers start like readers—that is how it was for me. I was like eight and felt the world needed a book about a girl who dressed up as a boy and accompanied Richard Lionheart as a page. My take on history was vague, my take on Richard was way too heroic, and my vocabulary was horribly tedious—and full of attempted medieval “speak” Agh! Many years later, I decided to really give writing a go, and once again I wrote a book that resonated with what I wanted to read. Seeing as I have always wanted to time travel—well, for short visits, deffo not to stay—my protagonist ended up being thrown back into the seventeenth century, because at the time, I was so fascinated by this period.

Sharon: Tell us about your books.

Anna: Well, I have just—today!—finished my 24th novel, supposedly a stand-alone, but according to my editor, I must write the rest of the story. So I probably will. Insert Graham Saga pic here! This is what always happens, you see. I start off writing ONE book and end up with one series after the other. My first series is The Graham Saga and is the story of Alex, my alter-ego time traveller who ends up in the 17th century where she meets Matthew Graham. Life will never be the same—not for Alex, not for Matthew, who has his doubts about this strange, borderline heathen woman who has landed at his feet. All in all, The Graham Saga is a ten (!!!!) book series, following Alex, Matthew and their expanding family through the latter half of the 17th century. Things happen to the Grahams—a lot of things, actually. Alex sometimes complains that it is too much, but between the two of us, she loves the adrenaline rushes I put her through! (“No, I don’t!” Alex growls. I just smirk) My second series is The King’s Greatest Enemy. I give you Adam de Guirande, an honourable knight who ends up torn between his love for his first lord, Roger Mortimer , and his loyalty to the young Edward III. Fortunately, he has a strong helpmeet in his wife, Kit. One book turned into four in this instance…

My third series is called The Castilian Saga and is set in the late 13th century. The lives and adventures of Robert FitzStephan, loyal captain to Edward I, and his wife, Eleanor d’Outremer, play out against the background of the conquest of Wales and the general upheaval in Castile and Aragon at the time. Yet another four book series…

I have also authored a three-book series called The Wanderer, which tells the story of Jason and Helle, brutally torn apart 3 000 years ago. After endless lives searching for his Helle, Jason finally finds her again and there is a HEA hovering on the horizon—had it not been for their nemesis last time round who has just gate-crashed the party. I loved writing this borderline fantasy/romantic suspense/ steamy series – but historical fiction is my first love and always will be.

I have an ongoing series called The Time Locket—and yes, it has a time travelling protagonist. Erin is of mixed race and find it very hard to navigate the early 18th century in the American Colonies—well, she finds it hard to navigate life in the 18th century, full stop. Fortunately, she has Duncan at her side. I’ve written two books in this series and have started on number three –but for some odd reason we seem to be going to St Petersburg—well, the building site that will become St Petersburg—and I am dragging my feet, despite Erin and Duncan constantly sending me evil looks.

And then, finally, we have my just finished Queen of Shadows. (The one that I now need to write a sequel to according to my editor) We are in 14th century Castile where King Alfonso XI is married to one woman, but loves another. Quite the soap opera—except it is a true story. Along the way, our stalwart king must vanquish Marinid invaders, rebellious nobles and handle a most incensed father-in-law. I don’t think I’ve ever spent as much time researching a novel as I have done with this one—I started toying with the idea already back in 2016.

I have also contributed to various short-story collections: Betrayal: Historical stories, Historical Stories of Exile and Fate: Tales of History, Mystery and Magic.

Phew! Quite a list, isn’t it? (Anna looks quite, quite pleased)

Sharon: What attracts you to the periods you write in?

Anna: The history. An event or a personage catches my attention, and off I go. During my recent visit to Dresden, I discovered just how complicated and delicious the history of Saxony is, but I hesitate re writing a book set there, because I don’t speak German, and I have learned the hard way that it helps if you know the language of the country you are writing about. Writing about Castile in the 14th century has required reading my way through bits and pieces of medieval Castilian chronicles—but as I am fluent in Spanish, I managed. I also had the opportunity to revisit all my old text books about the development of the Spanish language)

Sharon: Who is your favourite medieval person and why?

Anna: Seriously, ONE person? No, no, Sharon, how am I supposed to choose?? *Scratches head* Okay: in Castile, it would have to be Maria de Molina, I think. Wife of Sancho IV, she was firt regent to her son, Fernando IV, and when he was “summoned” (Yup, he’s known as Fernando the Summoned, given the odd circumstances of his death) she once again had to act as regent, now for her grandson, Alfonso XI. An extremely competent and wise woman, who suffered so much loss, so much heartbreak, but never gave up.

In England, I am going to say Edward I. Yes, yes, I can hear people going WHAT? THAT RAT BASTARD? – and yes, he deffo had rat bastard qualities, especially vis-à-vis Scotland and Wales, but he was also a competent, hard-working ruler who never quite got over the loss of his wife, Eleanor. When she died, his soft side more or less disappeared (although his second wife seems to have brought it out in him on occasion). Also, we must remember that Edward is a product of his time and of the events that shook his kingdom when he was still a young man—namely the rebellions that more or less stripped Edward’s father of all his kingly power.

Sharon: Who is your least favourite medieval person and why?

Anna: I’m not a big fan of The Black Prince, but my least favourite? Ah, yes: Simon Montfort the Elder, the man who led the Albigensian Crusade—or maybe Arnaud Amalric, the Cistercian abbot who purportedly ordered his men to kill all the people of Beziers during said crusade, stating that God would recognise his own (after death). Okay, so this is probably not true, but just the fact that an abbot actively participated in the massacre of the Cathars is rather icky, IMO. Sharon: I have to admit, I’m not a fan of either Simon de Montfort!

Sharon: How do you approach researching your topic?

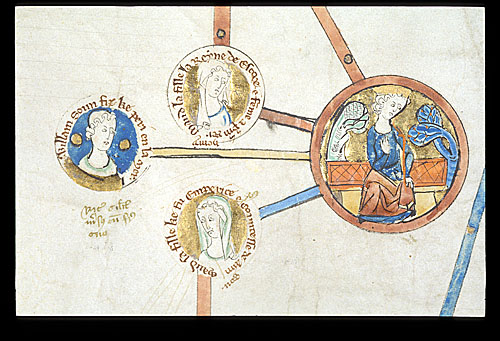

Anna: I start with one person, map out persons Person A interacted with and so on and so on. Plus, I always read an overview of the period first, highlighting things I will need to dig into. In my latest, it’s been a lot about sheep, about the Black Death, about coinage, about food—the Moors left a delicious legacy—about architecture. I also try to visit, to get a feel for the land as such. Good thing I did re my latest WIP, as it made me realise I was off by some kilometres from the sea in one of the more crucial scenes! insert pic of Sevilla

Sharon: Tell us your ‘favourite’ true historical story you have come across in your research.

Anna: Hmm. I am rather fond of the Edward-Eleanor love story. There he was, the future Edward I, all of fifteen when he married thirteen-year-old Eleanor. From that moment on, where he went, there went she.

Sharon: Tell us your least ‘favourite’ true historical story you have come across in your research.

Anna: Well, that is easy. In 1575, a seven-year-old little boy, Gustav Eriksson, was brutally exiled by his uncle, king Johan III of Sweden. Gustav was carried across the Baltic sea to Poland and there more or less abandoned, totally alone. No mother, no sister, no money. I have written about this sad little boy in Historical Stories of Exile (Sharon: How sad!)

Sharon: Are there any other eras you would like to write about?

Anna: I am rather fascinated by the period of the Second Great Awakening, i.e. the decades after the Napoleonic Wars. (Sharon: oooooooooh, yes please!)

Sharon: What are you working on now?

Anna: Well . . . I am dithering: should I start on that unplanned sequel by describing a wedding in 1353 at which an unwilling royal groom weds a French princess? Or should I dig into the mystery of the dead man in the barrel, come all the way from Russia before it ends up in Arabella Sterling’s warehouse? Or maybe I should work on both in parallel! (Sharon: Decisions! Decisions!)

Sharon: And finally, what is the best thing about being a writer?

Anna: I step into a world where I am totally in control (Muffled laughter from all my characters) OK, I escape into a world where I have some control—assuming my pesky characters cooperate. Somewhat more seriously, I love recreating life in the past, building that distant world brick by brick. Is the end creation an entirely correct representation? Of course not: there is so much we don’t know about that distant life—but I hope it gives a flavour!

Books by Anna Belfrage:

The Graham Saga Amazon US; Amazon UK; The King’s Greatest Enemy Amazon US; Amazon UK; The Castilian Saga Amazon US; Amazon UK; The Time Locket Amazon US; Amazon UK; The Wanderer Amazon US Amazon UK

About the Author:

Had Anna been allowed to choose, she’d have become a time-traveller. As this was impossible, she became a financial professional with three absorbing interests: history, romance and writing. Anna has authored the acclaimed time travelling series The Graham Saga, set in 17th century Scotland and Maryland, as well as the equally acclaimed medieval series The King’s Greatest Enemy which is set in 14th century England, and The Castilian Saga ,which is set against the medieval conquest of Wales. She has also published a time travel romance, The Whirlpools of Time, and its sequel Times of Turmoil, and is now considering just how to wiggle out of setting the next book in that series in Peter the Great’s Russia, as her characters are demanding. . .

All of Anna’s books have been awarded the IndieBRAG Medallion, she has several Historical Novel Society Editor’s Choices, and one of her books won the HNS Indie Award in 2015. She is also the proud recipient of various Reader’s Favorite medals as well as having won various Gold, Silver and Bronze Coffee Pot Book Club awards.

“A master storyteller” “This is what all historical fiction should be like. Superb.”

Find out more about Anna, her books and enjoy her eclectic historical blog on her website, http://www.annabelfrage.com

Social Media Links:

Bluesky: Facebook: Amazon Author Page

*

My books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online store.

Out now: Scotland’s Medieval Queens

Scotland’s history is dramatic, violent and bloody. Being England’s northern neighbour has never been easy. Scotland’s queens have had to deal with war, murder, imprisonment, political rivalries and open betrayal. They have loved and lost, raised kings and queens, ruled and died for Scotland. From St Margaret, who became one of the patron saints of Scotland, to Elizabeth de Burgh and the dramatic story of the Scottish Wars of Independence, to the love story and tragedy of Joan Beaufort, to Margaret of Denmark and the dawn of the Renaissance, Scotland’s Medieval Queens have seen it all. This is the story of Scotland through their eyes.

‘Scotland’s Medieval Queens gives a thorough grounding in the history of the women who ruled Scotland at the side of its kings, often in the shadows, but just as interesting in their lives beyond the spotlight. It’s not a subject that has been widely covered, and Sharon is a pioneer in bringing that information into accessible history.’ Elizabeth Chadwick (New York Times bestselling author)

Available now from Amazon and Pen and Sword Books

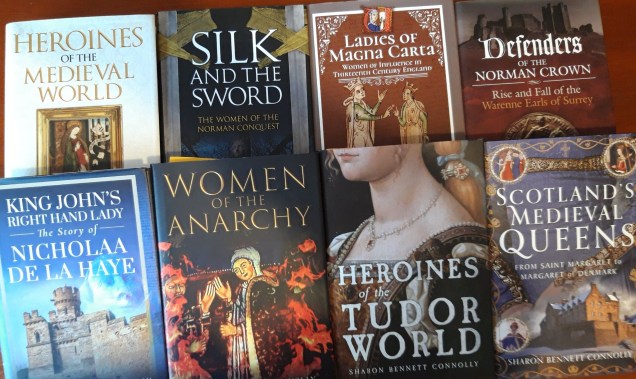

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. Heroines of the Tudor World is now available from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how Empress Matilda and Matilda of Boulogne, unable to wield a sword themselves, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It shows how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other. Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org. Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

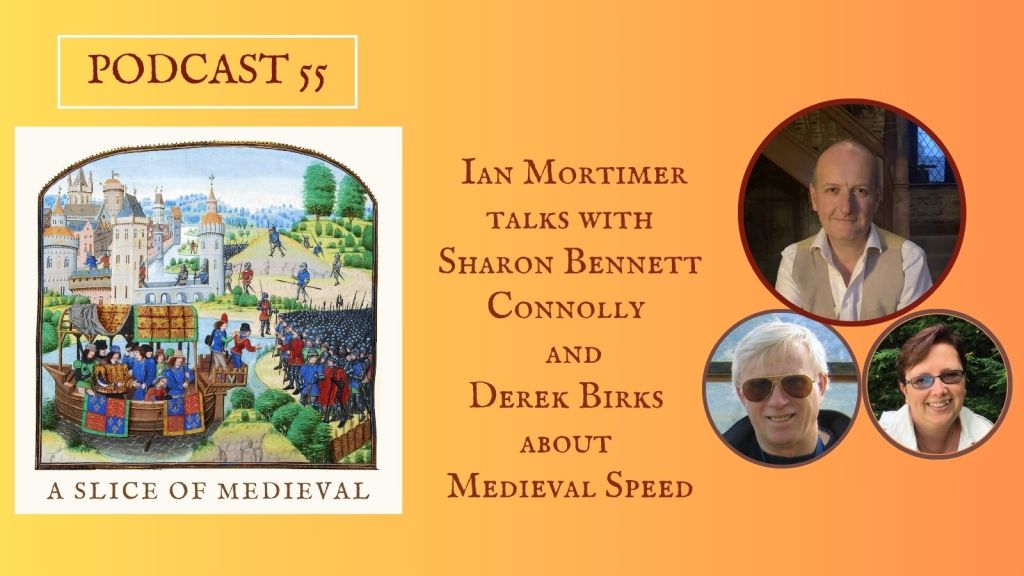

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell and Michael Jecks, and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved. There’s even an episode where we chat with Anna Belfrage about Edward I and Eleanor of Castile.

There are now over 75 episodes to listen to!

Every episode is also now available on YouTube.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online store.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter, Threads, Bluesky and Instagram.

*

©2025 Sharon Bennett Connolly and Anna Belfrage