Throughout history – and particularly in medieval times – strong, determined women have been labelled ‘she-wolves’. It is a term that has been used as a criticism or insult. It has often been applied to suggest a woman of serious character flaws who would invariably put her own interests ahead of others, who fought for what they wanted, be it a crown, their children or independence. Men who performed similar actions and had similar aims tended to be called strong and determined rulers. However, the term can also be used to show women in a positive light, women who didn’t give up, fought for themselves and their families. So I have chosen 6 women who could have been termed ‘she-wolves’ to show women from both viewpoints, and to demonstrate the strength of the characters and the challenges they faced. And while their actions were not always exemplary, their stories were always remarkable.

Here are the first 3:

Æthelflæd, Lady of Mercia

The daughter of King Alfred the Great, Æthelflæd was married to Æthelred, ealdorman of Mercia. Æthelflæd was a strong, brave woman and is often regarded more as a partner to Æthelred than a meek, obedient wife. Although she exercised regal rights in Mercia even before her husband’s death, after Æthelred died in 911, it was left to Æthelflæd to lead the Mercians in the fight against the Danes. Alongside her brother, King Edward of Wessex. It is universally acknowledged that Æthelflæd helped to push back the Viking incursions. Losing four of her greatest captains in the battle to capture Derby in 917, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reported:

‘With God’s help Ethelfleda, lady of Mercia, captured the fortress known as Derby with all its assets. Four of her favoured ministers were slain inside the gates.’

Anglo-Saxon Chronicles edited by Michael Swanton

In 918, Æthelflæd captured Leicester, ravaging the countryside around the town until the Danes surrendered. The combination of her indefatigable forces and compassion in victory saw the Danes soon suing for peace; in the summer of 918, the noblemen and magnates of York sent emissaries to Æthelflæd, promising that they would surrender to her. She personally led campaigns against the Welsh, the Norse and the Danes – though whether she actually wielded a sword in battle is unknown.

While often magnanimous in victory, Æthelflæd could be ruthless when it was her friends who were attacked; even she was not immune from the desire for revenge. In June 916, on the feast of St Cyriac, Æthelflæd’s good friend, Abbot Egbert, was murdered for no known reason. The Mercian abbot and his retainers were ambushed and killed while travelling in the Welsh mountain kingdom of Brycheiniog. The abbot had been under Æthelflæd’s protection and within three days she was leading an army into the Wales to exact revenge.

Æthelflæd’s army ravaged Brycheiniog, burning the little kingdom and taking many hostages. Although King Tewdr escaped Æthelflæd, his wife did not; Queen Angharad and thirty-three others, many of them relatives of the Welsh king, were taken back to Mercia as hostages. Æthelflæd’s strength and determination was complemented by her quick actions and an impressive ruthless streak. When the Welsh king eventually submitted to Æthelflæd, he promised to serve her faithfully, and to pay compensation for the murder of the abbot and his people.

Æthelflæd died suddenly in June 918. She did not live to see the successful conclusion to the work she and her brother had worked tirelessly to achieve; between 910 and 920 all Danish territories south of Yorkshire had been conquered.

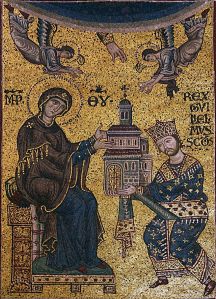

Eleanor of Aquitaine, Queen of France, Queen of England (died 1204)

Eleanor of Aquitaine is iconic. Probably the most famous woman of the middle ages, she is the only woman to have ever worn the crowns of both England and France. She has even been promoted as the first feminist.

Eleanor’s long life saw her weather the dangers of crusade, scandal, siege, imprisonment and betrayal to emerge as the great matriarch of Europe.

When her first husband, Louis VII, led the Second Crusade, Eleanor went with him, only to find herself mired in scandal. Eleanor’s uncle Raymond of Toulouse, Prince of Antioch, welcomed Eleanor warmly and lavished such attention on her that rumours soon arose of an affair. Despite a lack of concrete evidence, but accused of adultery and incest, Eleanor spent most of the crusade under close guard on her husband’s orders.

Louis and Eleanor’s marriage had been dealt a fatal blow; they left the Holy Land in 1149 and their divorce was finally proclaimed 21 March 1152. By May 1152 Eleanor was married again, to the man who would become her first husband’s greatest rival. Henry of Anjou would become King of England in 1154 and eventually built an empire that extended 1,000 miles, from the Scottish border in the north to the Pyrenees in the south and incorporating most of western France.

Later rumours again mired Eleanor in scandal, accusing her of murdering Henry’s lover Rosamund Clifford. In one extravagant version, Rosamund was hidden in her secret bower within a maze but, with the help of a silken thread, a jealous Eleanor still found her and stabbed her while she bathed. In another the discarded queen forced Rosamund to drink from a poison cup. Of course, a closely guarded prisoner in Old Sarum or at Winchester as Eleanor was at the time of Rosamund’s death, it was impossible for her to do any such thing. But who are we to let facts get in the way of a good story?

Eleanor did, however, commit one of the most heinous crimes a woman could in the medieval world. As a she-wolf, protecting her cubs, she rebelled against her husband. In 1173 her eldest son by Henry, also called Henry, rebelled against his father and fled to the French court for support. His father-in-law, King Louis VII welcomed the disgruntled Angevin prince and Eleanor of Aquitaine, having sided with her sons against her husband, sent two of her other sons, fifteen-year-old Richard and fourteen-year-old Geoffrey, to join their older brother at the French court, while she rallied her barons in Poitou to their cause. In 1174, when the rebellion failed, Henry accepted the submission of his sons.

Eleanor, who was captured as she rode towards safety in France, wearing men’s clothing – an act itself highly frowned upon – was not so fortunate. While it was not encouraged for sons to rebel against their father, it could be seen as boys flexing their muscles. For a wife to rebel against her husband was practically unheard of, and went against the natural order of society, and therefore deserved harsher punishment – where would the world be if women refused to behave?

Unforgiven and defeated, Eleanor was sent to perpetual imprisonment in various castles throughout southern England. She was only released after Henry II’s death in 1189, when her favourite son, Richard I, the Lionheart, ascended England’s throne. If she had done everything of which she was accused – murder, incest, adultery and rebellion – Eleanor would be the ultimate she-wolf. As it was, her rebellion, an act unprecedented for a queen, meant she paid the price with her freedom for the next fifteen years.

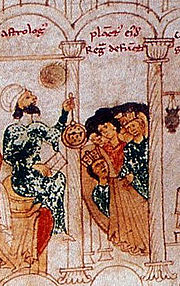

Isabeau of Bavaria, Queen of France

If all the stories of Isabeau of Bavaria were to be believed, she would be the most ruthless and wicked queen to have ever lived. For centuries Isabeau has been accused of almost every crime imaginable, from adultery and incest to treason and avarice. Variously described as being beautiful and hypnotic or so obese that she was crippled, the chroniclers have not been kind to Isabeau. According to them, her moral corruption led to the neglect of her children and betrayal of her husband and country.

However, they ignored the challenges faced by a queen whose husband was sinking deeper and deeper into the realms of insanity, going so far as killing four of his own knights during one mental breakdown and thinking he was made of glass in another. Married to King Charles VI of France, also known as Charles ‘the Mad’, Isabeau was left to raise her children and navigate the dangers and intrigues of court politics with little assistance from her mentally disturbed husband. Her political alliance with Louis of Orléans, her husband’s brother, led to her imprisonment amid slanderous rumours of adultery and incest – from the opposing political party.

To add to this, France was – not that they knew it at the time – halfway through the conflict with England that would become known as the Hundred Years’ War. The war was going badly for France – Henry V defeated them decisively at Agincourt – and Isabeau was forced to put her signature to the Treaty of Troyes in 1420. In that instant she disinherited her own son, the Dauphin, making Henry V heir to King Charles and handing France over to England. Much of Isabeau’s life and career has been re-examined in the twentieth century and she has been exonerated of many of the accusations against her, but, despite the fact Isabeau was backed into a corner, she still signed away her son’s inheritance in favour of a foreign power…

Although not all their actions were womanly, and some of what they did could be seen as dishonourable and ruthless, what is certain is that these women – and many others from their time – left their mark on history. With each of them, applying the term ‘she-wolf’ highlights their strengths, their determination, and the challenges they faced and overcame. They fought for what they wanted, often against impossible odds, and achieved much. At a time when the perceived main purpose of a wife was to produce and raise children, these women made a remarkable imprint on history that has ensured their stories are still being told today.

Look out for Part Two of Medieval She-Wolves, next week.

Selected Sources:

The Oxford Companion to British History Edited by John Cannon; The Plantagenets, the Kings who Made England by Dan Jones; History Today Companion to British History Edited by Juliet Gardiner and Neil Wenborn; Brewer’s British Royalty by David Williamson; Britain’s Royal Families, the Complete Genealogy by Alison Weir; The Plantagenet Chronicles Edited by Elizabeth Hallam; The Mammoth Book of British Kings and Queens by Mike Ashley; The Plantagenets, the Kings that made Britain by Derek Wilson; England Under the Norman and Angevin Kings by Robert Bartlett; http://www.britannica.com; oxforddnb.com; finerollshenry3.org.uk; The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles by Michael Swanton; The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle by James Ingram; Chronicles of the Kings of England, From the Earliest Period to the Reign of King Stephen, c. 1090–1143 by William of Malmesbury; The Chronicle of Henry of Huntingdon by Thomas Forester; Alfred the Great by David Sturdy; Britain’s Royal Families, the Complete Genealogy by Alison Weir; The Wordsworth Dictionary of British History by JP Kenyon; The Anglo-Saxons in 100 Facts by Martin Wall; Kings, Queens, Bones and Bastards by David Hilliam; Mercia; the Rise and Fall of a Kingdom by Annie Whitehead.

Images courtesy of Wikipedia

A version of this article first appeared in the 2019 edition of All About History magazine.

My Books:

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

Out Now! Women of the Anarchy

Two cousins. On the one side is Empress Matilda, or Maud. The sole surviving legitimate child of Henry I, she is fighting for her birthright and that of her children. On the other side is her cousin, Queen Matilda, supporting her husband, King Stephen, and fighting to see her own son inherit the English crown. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how these women, unable to wield a sword, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It show how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other.

Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK.

Coming on 15 June 2024: Heroines of the Tudor World

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. These are the women who made a difference, who influenced countries, kings and the Reformation. In the era dominated by the Renaissance and Reformation, Heroines of the Tudor World examines the threats and challenges faced by the women of the era, and how they overcame them. From writers to regents, from nuns to queens, Heroines of the Tudor World shines the spotlight on the women helped to shape Early Modern Europe.

Heroines of the Tudor World is now available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK.

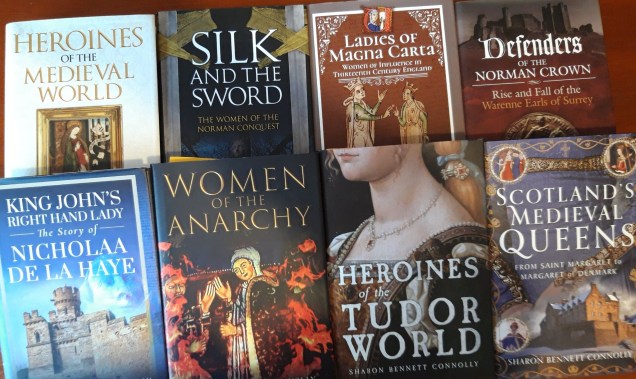

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. It is is available from King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops or direct from Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon. Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org.

Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell and Elizabeth Chadwick, and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

*

©2019 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS