Few women in the medieval era were able to take the reins of government. Their role was primarily confined to the domestic sphere, with men taking on the job of governance – whether of lands, as a count or duke, or of a country, as king – because that was seen as their domain. Some women, however, did manage to rule, and to rule efficiently, although not without opposition. Most examples of women who took the reins of power follow the early deaths of their husbands, when they were called upon to rule as regents until their sons were old enough to rule alone.

One such woman was Anna of Kyiv, sometimes called Agnes. Born some time between 1024 and 1036, Anna was the daughter of Yaroslav the Wise, Grand-Duke of Kyiv, and Ingegerd of Sweden. Yaroslav and Ingegerd had nine children, several of whom had made royal marriages. Of their daughters, Anastasia had married Andrew I of Hungary, and Elizabeth (Elisiv) was the wife of Harold (Hardrada) of Norway. One son, Isiaslav, was married to the sister of the king of Poland, while another son, Vsevolod, married a daughter of the Byzantine emperor.

In 1051, Anna was to make the most prestigious marriage of all, when she became the second wife of Henry I, King of France. Following the death of his first wife, Matilda of Frisia, during childbirth, and in an attempt to find a wife who was not related to him within the Church’s prohibited degrees of kinship, Henry had sent an ambassador to Kyiv, laden with gifts, in search of a bride. Anna is said to have been renowned throughout Europe for her ‘exquisite beauty, literacy and wisdom’.1 Anna and Henry were married at the Cathedral of Reims on 19 May 1051; Anna was probably around twenty years old, while Henry was around forty-three.

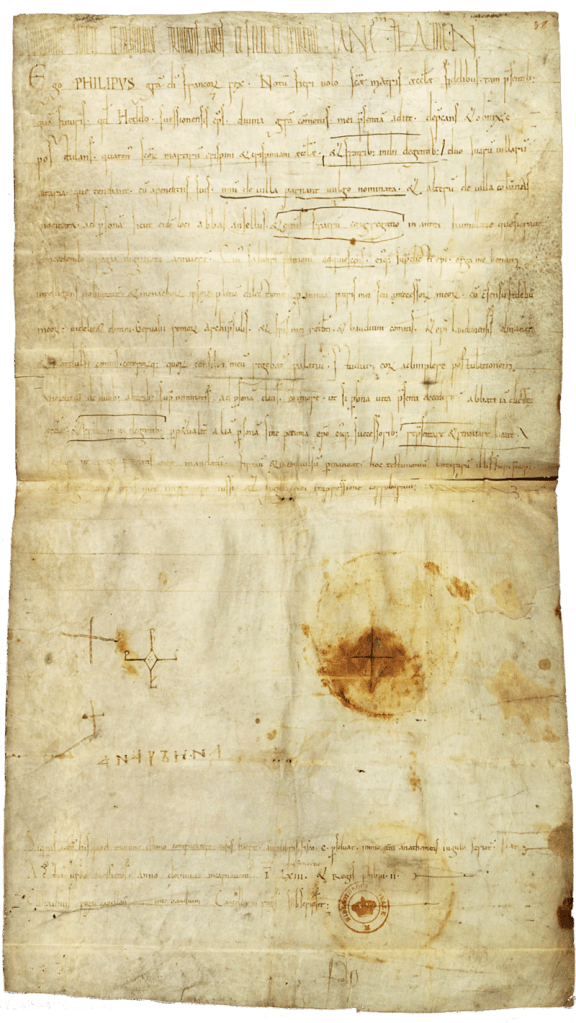

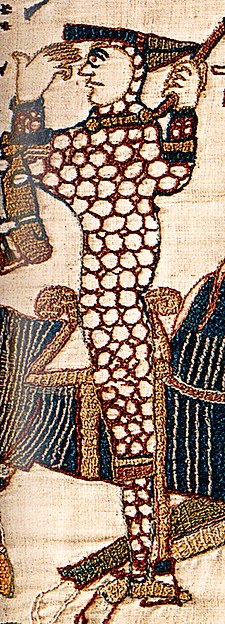

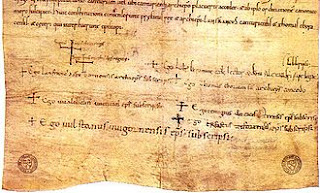

As a demonstration of her superior level of education, Anna signed the marriage contract in her own hand, using her full name, whereas Henry could only manage a cross. At her coronation at Reims, Anna used a Slavic gospel to say her vows, which she had brought with her from Kyiv, rather than the traditional Latin Bible. Anne brought no land with her marriage dowry, but she did bring connections and wealth. The jewels she brought with her probably included a jacinth, which Abbot Suger later mounted in a reliquary of St Denis.2

Although it lasted only nine years, Anna and Henry’s marriage appears to have been a great success. The couple had three sons, of whom the oldest, Philip, born in 1052, succeeded his father as Philip I. He was known as Philip ‘the Amorous’ and reigned for forty-eight years, marrying twice; firstly to Bertha of Holland and secondly to Bertrade de Montfort, having three children – two sons and a daughter – with each wife. Anne and Henry’s second son, Robert, born in 1054/5, died young and the youngest, Hugh, born in 1057, became Count of Vermandois on his marriage to Adelaide, Countess of Vermandois. Hugh was vilified for failing to fulfil his Crusader vows by returning home early from the First Crusade, he died, in 1101, of wounds received in battle with the Turks after returning to the Holy Land. One of Hugh’s nine children, his daughter, Isabel de Vermandois, was married to Robert de Beaumont, Earl of Leicester, before her father departed on crusade, even though she was only aged 10 or 11 at the time. Isabel would marry, as her second husband, William de Warenne, 2nd Earl of Warenne and Surrey.

Anna appears to have thought of France as provincial compared to her homeland of Kyiv; she is said to have written to her father in 1050 saying, ‘What a barbarous country you sent me to – the dwellings are sombre, the churches horrendous and the morals – terrible’.3 Anna, however, appears to have made an effort to settle into her adopted country, she learned the language and participated, to some extent, in government; she and Henry worked in partnership as king and queen. Several decrees include the phrase ‘With the consent of my wife Anna’ or ‘In the presence of Queen Anna’.4

Towards the end of Henry’s reign, Anna was counter-signatory to at least four charters, including a 1058 charter of concession to the monastery of St Maur-les-Fosses, signed ‘including my wife Anna and sons Philip, Robert and Hugh’ and a donation to the monastery at Hasnon, which was signed by King Henry, Prince Philip and Queen Anna.5

The situation changed in 1060 when King Henry died. With Anna’s son Philip then only seven years old, a regency was set up with Baldwin V of Flanders as regent. He was the husband of King Henry’s sister Adele, and father of Matilda of Flanders, Queen of England. However, at the time, the Bishop of Chartres described Philip and his mother Anna as his sovereigns; moreover, Philip himself declared that, as a child, he ruled the kingdom jointly with his mother. The young king valued his mother’s advice and Anna signed numerous royal acts during her son’s reign; her signature was always either the first signature on the document or the second after that of King Philip. The acts included donations to monasteries, the renunciation of customs grants of exemptions and a charter to the Abbot of Marmoutier to build a church. In all, there are at least twenty-three acts that mentioned Anna, or carried her signature, between 1060 and 1075.6

Anna was held in high regard by many. Among her admirers was Pope Nicholas II himself, who wrote to her with high praise;

Nicholas, Bishop, servant of the servants of God, to the glorious queen, greeting and apostolic benediction. We give proper thanks to almighty God, the author of good will, because we have heard that the virile strength of virtues lives in a womanly breast. Indeed it has come to our ears, most distinguished daughter, that your serenity overflows with the munificence of pious generosity for the poor, sweats forth with the zeal of most devoted prayer, administers the force of punishment on behalf of those who are violently oppressed, and fulfills with other good works, insofar as it belongs to you, the office of royal dignity…7

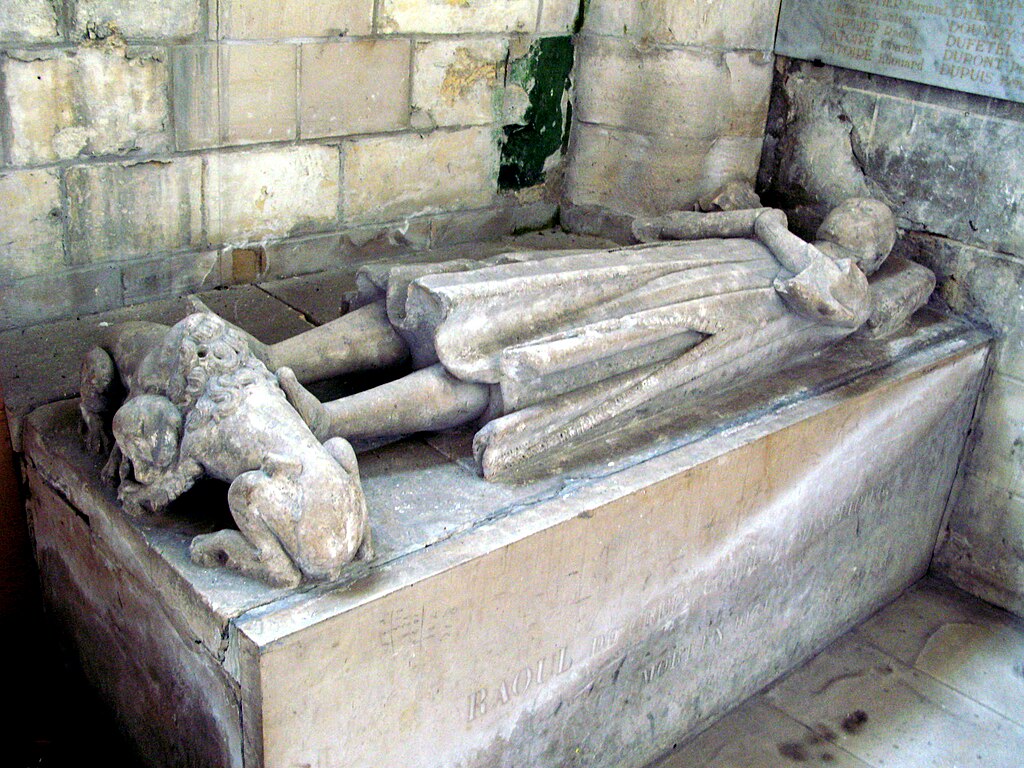

In 1061 Anna was involved in a scandal in France when she married Raoul, Count of Crepy and Valois, in what appears to have been a love-match. Raoul was an ally of the young king, but was already married to Eleanor. Eleanor’s family name is identified as “Haquenez” in two primary sources, but her origins are obscure. The count had repudiated Eleanor, on the grounds of adultery, in order to marry Queen Anna. However, Eleanor appealed to the pope, Alexander II, who ordered the Archbishop of Reims to investigate the matter.

Raoul was ordered to take Eleanor back, and was excommunicated when he refused; he and Anna left court as a result of the furore. However, Raoul and Anna were both important allies of the king, and continued advising Philip and acting as signatories to his royal acts, despite being exiled from the court. The king eventually forgave his mother and she was welcomed back to court following Raoul’s death in 1074. Her return to her family was probably short-lived, however, as it seems likely that Anna died in 1075, although the exact date of her death, and her final resting place, are lost to the thousand years that have passed since then.

Anna of Kyiv left a mark on history in the remarkably high regard in which both her husband, Henry I, and her son Philip held her. She was a well-educated, pious woman whose advice and opinions were respected, not only within her family, but by such exalted persons as the pope and French bishops.

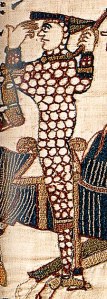

She proved that a woman could act wisely, at least in politics, if not in her second marriage, at a time when women were not expected, or allowed, to rule. The nature of her rule appears to have been a gentle hand on the shoulder of her son, whereas other women were more forceful as rulers – such as Adela of Normandy, Countess of Blois, the daughter of William the Conqueror, King of England, and Matilda of Flanders.

*

Images:

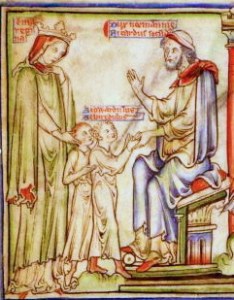

Courtesy of Wikipedia

Notes:

1. Prominent Russians: Anna Yaroslavna (article), russiapedia.rt.com/prominent-russians/the-ryurikovich-dynasty/anna-yaroslavna; 2. epistolae.ccnmtl.columbia.edu, Anne of Kiev (Anna Yaroslavna) (article). Quoted from Bauthier, 550; Hallu, 168, citing Comptes de Suger; 3. Prominent Russians: Anna Yaroslavna; 4. Moniek Bloks, Anne of Kiev, the First Female Regent of France; 5. epistolae.ccnmtl.columbia.edu, Anne of Kiev (Anna Yaroslavna) (article). The St Maur-les-Fosses charter reads ‘annuente mea conjuge Anna et prole Philippo, Roberto ac Hugone’; 6. epistolae.ccnmtl.columbia.edu, Anne of Kiev (Anna Yaroslavna) (article); 7. Letter from Pope Nicholas II to Anne of Kiev, October 1059, epistolae.ccnmtl.columbia.edu/letter/1190, translated by Ashleigh Imus.

Sources:

Prominent Russians: Anna Yaroslavna (article), russiapedia.rt.com/prominent-russians/the-ryurikovich-dynasty/anna-yaroslavna; epistolae.ccnmtl.columbia.edu, Anne of Kiev (Anna Yaroslavna) (article); Moniek Bloks, Anne of Kiev, the First Female Regent of France; Heroines of the Medieval World by Sharon Bennett Connolly; Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest by Sharon Bennett Connolly; Matilda by Tracy Borman; The Norman Conquest by Marc Morris; Elisabeth M.C. Van Houts and Rosalind C. Love (eds and trans), The Warenne (Hyde) Chronicle; W.S. Davis, A History of France from the Earliest Times to the Treaty of Versailles; Emily Joan Ward, Anne of Kiev (c.1024–c.1075) and a reassessment of maternal power in the minority kingship of Philip I of France (article); Charlotte M. Yonge, History of France; Pierre Goubert, The Course of French History

*

My Books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online store.

Out now: Scotland’s Medieval Queens

Scotland’s history is dramatic, violent and bloody. Being England’s northern neighbour has never been easy. Scotland’s queens have had to deal with war, murder, imprisonment, political rivalries and open betrayal. They have loved and lost, raised kings and queens, ruled and died for Scotland. From St Margaret, who became one of the patron saints of Scotland, to Elizabeth de Burgh and the dramatic story of the Scottish Wars of Independence, to the love story and tragedy of Joan Beaufort, to Margaret of Denmark and the dawn of the Renaissance, Scotland’s Medieval Queens have seen it all. This is the story of Scotland through their eyes.

‘Scotland’s Medieval Queens gives a thorough grounding in the history of the women who ruled Scotland at the side of its kings, often in the shadows, but just as interesting in their lives beyond the spotlight. It’s not a subject that has been widely covered, and Sharon is a pioneer in bringing that information into accessible history.’ Elizabeth Chadwick (New York Times bestselling author)

Available now from Amazon and Pen and Sword Books

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. Heroines of the Tudor World is now available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how Empress Matilda and Matilda of Boulogne, unable to wield a sword themselves, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It shows how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other. Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org. Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell, Helen Castor and Michael Jecks, and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

Every episode is also now available on YouTube.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online store.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter, Threads, Bluesky and Instagram.

*

©2025 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS