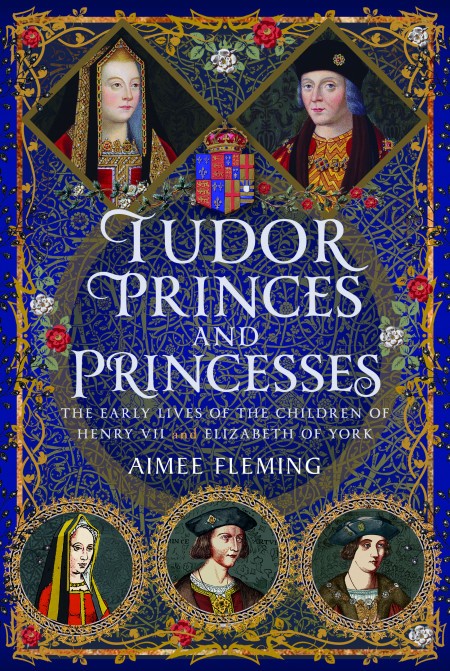

Today, it is a pleasure to welcome Aimee Fleming to History…the Interesting Bits. Aimee’s first book, The Female Tudor Scholar and Writer: The Life and Times of Margaret More Roper was a wonderful biography of Thomas More’s famous scholarly daughter. Aimee is now back with a second book, looking into the lives of the first royal Tudor children, Tudor Princes and Princesses: The Early Lives of the Children of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York. And she has written a little piece as a taster of the treat that is this wonderful book. Over to Aimee…

When Henry VII and Elizabeth of York married in January 1486, it was clear to them that their most important task ahead was to stabilise England, and the best, perhaps easiest way available to them was to produce an heir, and quickly.

However, bearing a child in the fifteenth century was not an easy feat, even for a Queen. Science and medicine were far from helpful, and the practices of the time meant that pregnancy and childbirth were dangerous to everyone involved. Elizabeth had her family around her, her mother who had had twelve children would have been invaluable to her, but the risks to herself, her child, and to her husband’s reign would have been very clear indeed.

In this extract we see how the couple prepared for their new arrival, and what Elizabeth herself was required to do, even before the rigours of birth.

Extract from Chapter 2 of Tudor Princes and Princesses

Following the wedding ceremony in January 1486, the royal couple remained in London and held court over celebrations in their honour, with spectacular banquets and dances. The celebrations were held all over London and further afield. As Bernard André describes:

‘…the most wished day of marriage was celebrated by them

with all religious and glorious magnificence at court, and

by their people, to show their gladness with bonfires,

dancing, songs and banquets throughout all London,

both men and women, rich and poor, beseeching God to

bless the King and Queen and grant them a numerous

progeny.’

This outpouring of support for the marriage of the king and queen was welcomed by all, especially by Henry and Elizabeth themselves, who knew just how important it was that their union, and rule, be accepted. It became apparent that their marriage represented the potential for peace in the form of an heir who would have their claims combined within him. Hall’s Chronicle shows what was expected.

‘By reason of whiche manage peace was thought to discende out of heaue into England, consideryng that the lynes of Lancastre & Yorke, being both noble families equiualet in ryches, fame and honour, were now brought into one knot and connexed together, of whose two bodyes one heyre might succede, which after their lyme should peaceably rule and enioye the whole monarchy and realme of England.’

Confident in their position early on, the king and queen worked to secure the future that so many hoped for and very soon after their wedding took place it was announced that the queen was with child. Whether that be out of duty, mutual respect, or genuine affection and love between them, the conception of a child was joyous news for all involved. Calculating from the date of their wedding, and Arthur’s birth, it is reasonable to assume that they conceived quickly, if not on their wedding night itself. When Henry departed for a progress around Yorkshire and Lincolnshire in the early spring of 1486, he did not take Elizabeth with him, most likely because she was suffering from morning sickness, or other symptoms associated with the early stages of pregnancy. As a first-time mother, it would have been new to Elizabeth, but luckily, she had her experienced mother and mother-in-law both around to support her. While Henry was travelling, he sent regular letters to his new wife, and would send gifts to her while she stayed at the Palace of Placentia.

Elizabeth would have been familiar with the palace, having spent a lot of time there as a young girl. It would become one of the most favoured for the king and queen and would be renamed by Henry as Greenwich Palace. Both names emphasise how the palace was surrounded by green parks and fields, isolated from the hustle and bustle and potential diseases of London itself.

As soon as it could be confirmed that Elizabeth was with child, the wheels began turning to arrange yet more elaborate ceremony, intended to cement Elizabeth as queen, the Tudor dynasty as the ruling family, and rightfully on the throne. This started with Elizabeth’s care while pregnant.

While it was not common for pregnant women to receive medical or ante-natal care in this period, Elizabeth’s health would have been monitored and her diet checked, and healthy habits encouraged by her ladies and physicians. Pregnant women were discouraged from heavy activities or stressful situations, and sometimes forbidden to eat certain foods; for example, if a woman complained of morning sickness, she may be told to limit her intake of fish or milk, both of which modern doctors would recommend she eat.

Pregnancy was dangerous, as was childbirth, for both the mother and the child, so royal women were given the best possible conditions in which to give birth, according to the science of the time.

As a woman’s due date got closer, she would be expected to enter confinement. This was a time where the pregnant woman and her household would isolate themselves in the woman’s bedroom. Windows would be barred and draped, and air flow would be completely stifled as it was believed that illnesses were carried on the air. For a queen, preparations for confinement would be made by the king according to traditions laid out during the reign of Edward IV, Elizabeth’s father. She would have been very familiar with the work that needed to be done, and the fact that the arrangements would be made for her by her husband.

Henry took his role in arranging Elizabeth’s confinement very seriously indeed. He purchased clothes and bedding for the chambers, all made of furs and velvet, and the most luxurious cotton sheets. He arranged for new furniture for her rooms and cushions stuffed with feathers, and even, bewilderingly, two velvet-covered saddles.

However, by far the most important decision that Henry made regarding his wife’s confinement and birth experience was to choose the location, and for Henry there was only one place that it could happen and that was the city of Winchester.

About the Author:

Aimee Fleming is a historian and author from North Yorkshire. She is happily married, with three growing boys and a whole host of pets. She studied history at the University of Wales, Bangor and then later completed a masters in Early Modern History at the University of York as a mature student. She has a passion for history, particularly the Tudors, and worked for over a decade in the heritage industry in a wide variety of roles and historic places.

Books by Aimee Fleming:

The Female Tudor Scholar and Writer: The Life and Times of Margaret More Roper

Tudor Princes and Princesses: The Early Lives of the Children of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York

Where to find Aimee:

Website; Facebook; Threads and Instagram: @historyaimee; Substack.

*

My books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online store.

Out now: Scotland’s Medieval Queens

Scotland’s history is dramatic, violent and bloody. Being England’s northern neighbour has never been easy. Scotland’s queens have had to deal with war, murder, imprisonment, political rivalries and open betrayal. They have loved and lost, raised kings and queens, ruled and died for Scotland. From St Margaret, who became one of the patron saints of Scotland, to Elizabeth de Burgh and the dramatic story of the Scottish Wars of Independence, to the love story and tragedy of Joan Beaufort, to Margaret of Denmark and the dawn of the Renaissance, Scotland’s Medieval Queens have seen it all. This is the story of Scotland through their eyes.

‘Scotland’s Medieval Queens gives a thorough grounding in the history of the women who ruled Scotland at the side of its kings, often in the shadows, but just as interesting in their lives beyond the spotlight. It’s not a subject that has been widely covered, and Sharon is a pioneer in bringing that information into accessible history.’ Elizabeth Chadwick (New York Times bestselling author)

Available now from Amazon and Pen and Sword Books

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

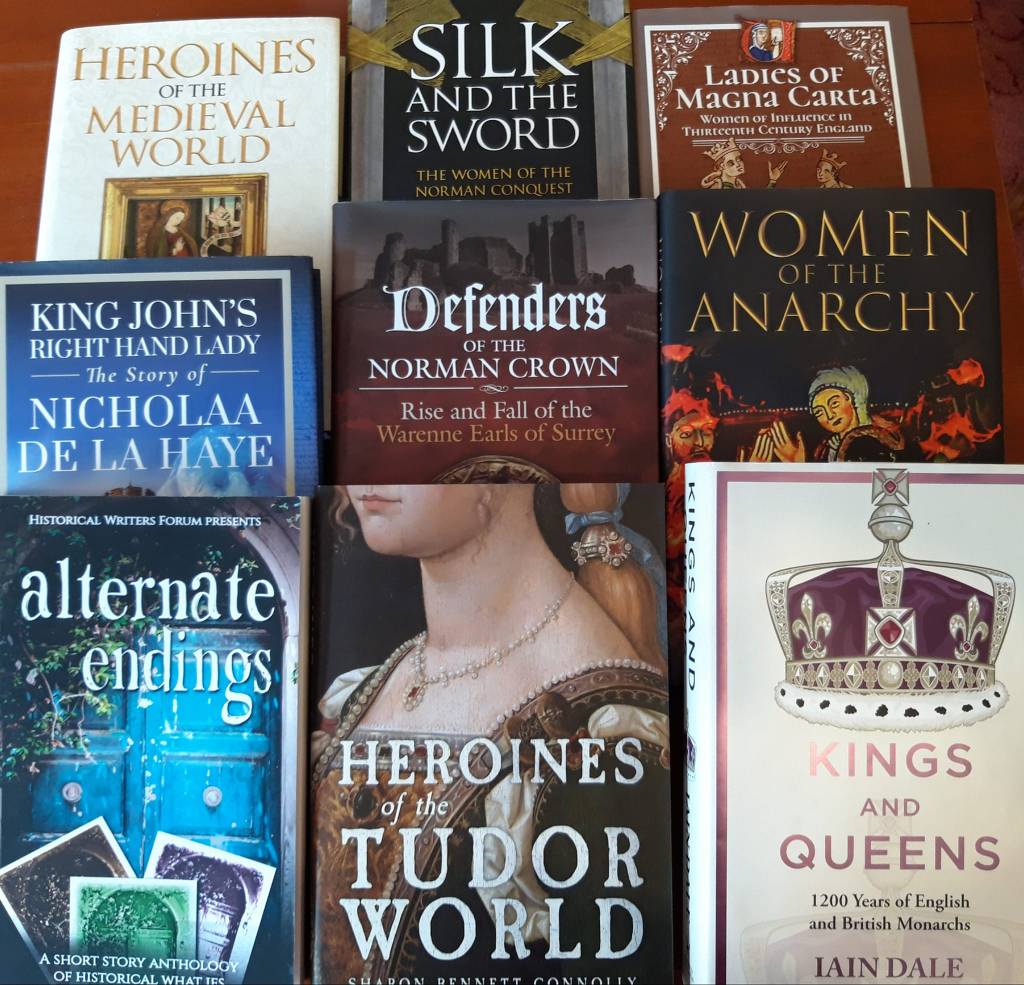

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. Heroines of the Tudor World is now available from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how Empress Matilda and Matilda of Boulogne, unable to wield a sword themselves, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It shows how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other. Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org. Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell and Michael Jecks, and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

Every episode is also now available on YouTube.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online store.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter, Threads, Bluesky and Instagram.

*

©2025 Sharon Bennett Connolly, FRHistS and Aimee Fleming