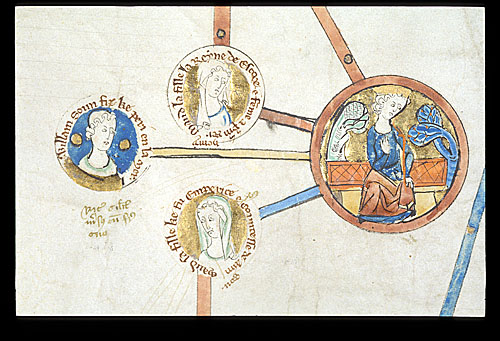

Matilda of Scotland was the daughter of Malcolm III Canmore, King of Scots, and his wife, the saintly Queen Margaret. With Margaret’s descent from Alfred the Great, Matilda not only had the blood of Scottish kings flowing through her veins but also that of England’s Anglo-Saxon rulers. Born in the second half of 1080, Matilda was named Edith at her baptism, her name being changed to Matilda at the time of her marriage, most likely to make it more acceptable to the Norman barons. To avoid confusion, we will call her Matilda for the whole article.

The baby princess’s godfather was none other than Robert Curthose, who was visiting Scotland at the time of her birth. Her godmother was England’s queen, Matilda of Flanders. She and her younger sister, Mary, who was born in 1082, were sent to England to be educated by their maternal aunt Christina, at Romsey Abbey in 1086. A nun who spent time at both Romsey and Wilton abbeys, Christina was said to have treated Matilda harshly, the young princess constantly ‘in fear of the rod of my aunt’.1 Christina’s treatment of Matilda was made public during a church inquiry into whether or not Matilda had, in fact, been professed as a nun, at which point Matilda made her striking references to the ‘rage and hatred … that boiled up in me’.2

Before 1093 the two Scottish princesses, now approaching their teens, had moved on to Wilton Abbey to continue their education, away from the harsh discipline of their aunt. Like Romsey, Wilton was a renowned centre for women’s education and learning. It could accommodate between eighty and ninety women, and was once patronised by Edward the Confessor’s wife, Edith of Wessex. The abbey had a reputation for educating women from the highest echelons of the nobility and the royal family itself; the girls’ mother, Queen Margaret, had also been sent to Wilton to be educated after arriving in England in the late 1050s. The abbey was a popular destination for pilgrims, housing among its relics ‘a nail from the True Cross, a portion of the Venerable Bede and the body of St Edith’.3 Matilda’s first language was English, but she is known to have spoken French at Wilton. She also learned some Latin, read both the old and new testaments of the Bible, ‘the books of the Church fathers and some of the major Latin writers’.4

By 1093, thoughts were turning to Matilda’s future, but politics intervened. King Malcolm had a disagreement with King William II Rufus after which ‘they parted with great discord, and the king Malcolm returned home to Scotland.’5 On his way home, Malcolm stopped at Wilton to collect his daughters. On his arrival, he found Matilda wearing a veil. The Scots king ripped the offending item from his daughter’s head, tearing it to pieces before trampling the garment into the earth.

Malcolm III insisted that the two girls were not destined for the religious life.

Father and daughters then returned to Scotland, only to find Queen Margaret was ailing, her health had been deteriorating gradually for some time. Despite the queen’s illness, King Malcolm took two of his sons and an army into England, raiding Northumberland. Malcolm and his eldest son, Edward, were killed. Queen Margaret was told the news just a few days later and died shortly after. Having lost both parents in such a short space of time, the two princesses were taken back south by their uncle Edgar the Ӕtheling, though whether they stayed at a convent or resided at court is unclear. Mary would eventually be married to Eustace III, Count of Boulogne, and was the mother of Matilda of Boulogne, wife of King Stephen.

Matilda herself was not short of suitors, who included Alan the Red, Count of Richmond and William de Warenne, Earl of Surrey. Orderic Vitalis explains:

Alain the Red, Count of Brittany, asked William Rufus for permission to marry Matilda, who was first called Edith, but was refused. Afterwards, William de Warenne, Earl of Surrey, asked for this princess; but reserved for another by God’s permission, she made a more illustrious marriage. Henry, having ascended the English throne, married Matilda.6

As events unfolded, Matilda was caught up in accusations and scandal surrounding her erstwhile nunnery at Wilton. She refused to return to the convent and insisted that she had never intended to dedicate herself to the church. When Archbishop Anselm ordered Osmund, Bishop of Salisbury to retrieve this ‘prodigal daughter of the king of Scots whom the devil made to cast off the veil’, the princess stood firm and defied him.’7

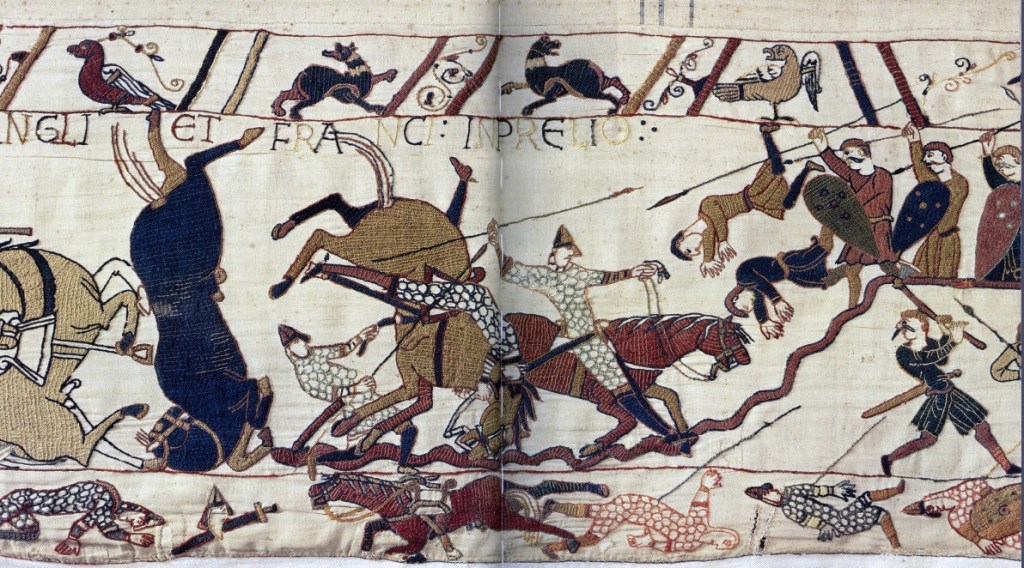

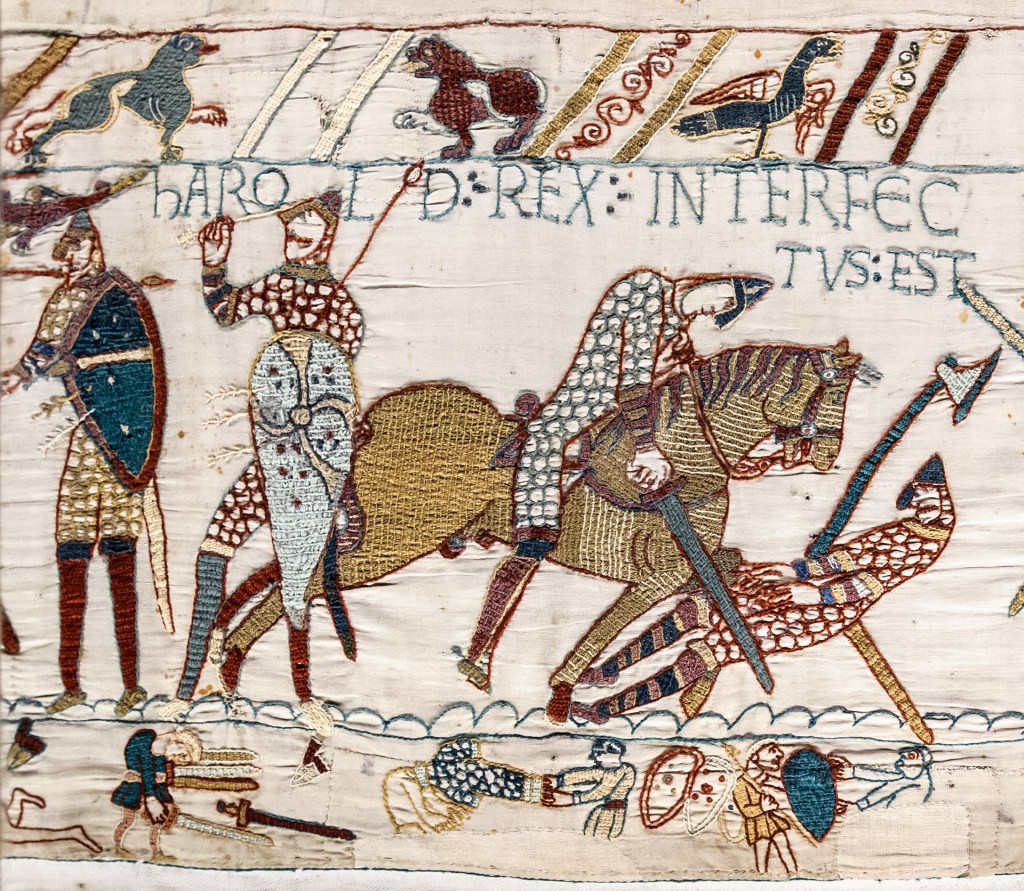

William II Rufus was famously killed in a hunting accident in the New Forest on 2 August 1100, shot by an arrow loosed by Walter Tirel. William II’s youngest brother, Henry, who was among the hunting party, wasted no time grieving his brother’s death. Leaving the dead king’s body to be looked after by others, he rode fast for Winchester. He seized control of the royal treasury before heading to London and his coronation, which took place on 5 August, just three days after William II’s death. Henry’s surviving older brother, Robert, was still on his way home from the Crusades, unable to take advantage of William’s death to claim the English crown for himself. The newly crowned King Henry I now needed a wife and settled on Matilda of Scotland.

The marriage was not without controversy, however, and before it could take place the church conducted an inquiry into the suggestion that Matilda was a runaway nun. Although Matilda vehemently rejected the claim that she had been professed as a nun, the fact witnesses had seen her wearing a veil on multiple occasions counted against her. Matilda appealed to Archbishop Anselm to look into the matter. The archbishop was appalled at the thought a religious vow may have been broken and declared that he ‘would not be induced by any pleading to take from God his bride and join her to any earthly husband’.8 After meeting with Matilda personally, and hearing her side of the story, the archbishop was persuaded to call an ecclesiastical council to decide the matter. Using Archbishop Lanfranc’s previous ruling that Anglo-Saxon women who had sought refuge in a convent after the Norman Conquest ‘could not be held as sworn nuns when they emerged from hiding’, the council ruled in Matilda’s favour.9 The council determined that ‘under the circumstances of the matter, the girl could not rightly be bound by any decision to prevent her from being free to dispose of her person in whatever way she legally wished’.10

When the wedding finally went ahead, Archbishop Anselm related the controversy over Matilda’s status to the gathered congregation and asked if there were any objections. According to Eadmer, ‘The crowd cried out in one voice that the affair had been rightly decided and that there was no ground on which anyone … could possibly raise any scandal.’11

Henry I married Matilda of Scotland on 11 November 1100, at Westminster Abbey, her name officially and permanently changed from Edith. Marriage between Henry and Matilda represented a continuity of the old Anglo-Saxon royal line; an heir produced by the royal couple would be heir to both the Norman royal house and the ancient royal house of Wessex, creating a genuine unifying force within England. The marriage was also a union between the royal houses of England and Scotland. Offering the promise of peace on England’s troublesome northern border, it would allow Henry to look to his interests on the continent and watch for the return of his older brother, Robert, from crusade.

The honeymoon period for the royal couple was was short-lived and in 1101, Robert had returned and heard of King William’s death and Henry’s seizure of the crown. The duke sent messengers to Henry, asking him to hand over the kingdom. Henry refused. It probably came as no surprise to Henry, then, when Robert invaded England on 20 July 1101. One chronicler claimed that Matilda was in childbed at this time; if she was, the child did not survive. More likely given the timing is that the queen was having a difficult early pregnancy with Matilda, who was born seven months later.

Neither side, however, was keen on all-out war, especially a civil war, and peace talks began almost immediately as the two armies of the royal brothers came face to face at Alton. In the subsequent Treaty of Alton, the duke accepted an annuity of 3,000 marks, drawn from the revenues of England, to abandon his invasion and renounce his claims to the throne. In return, King Henry renounced his lands in Normandy save for Domfront, where he had made a solemn vow to the inhabitants that he would never relinquish control. The brothers agreed to support each other should either be attacked by a third party, and to be each other’s heir if neither sired a son.

Robert returned to Normandy but would soon be pulled back to England by a sense of chivalric duty to his barons. The agreement at Alton between the brothers had left Earl William II de Warenne isolated and at Henry’s mercy. For violating his oath of homage to the king, and for violence perpetrated by his men in Norfolk, Earl Warenne’s English estates were declared forfeit and he was effectively forced to cross the English Channel into exile. Earl William complained to Duke Robert of his sufferings and losses on the duke’s behalf. The duke obviously felt some responsibility, as he set out for England to intercede with his brother on the earl’s behalf. Robert arrived at Henry’s court, uninvited and unwelcome, in 1103. Threatened with imprisonment by an angry brother, he was persuaded by Queen Matilda, to relinquish his annuity of 3,000 marks in return for the reinstatement of Earl William’s English estates and titles.

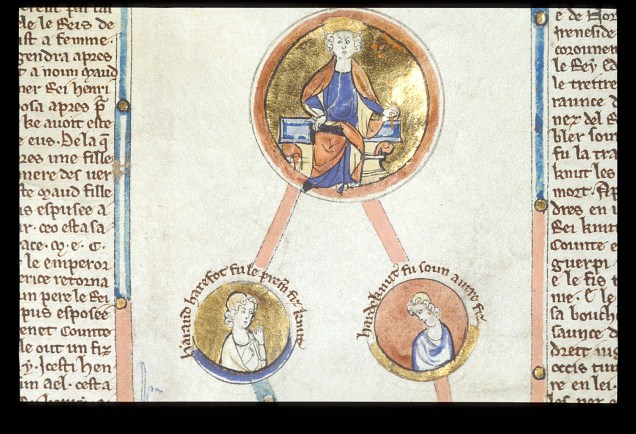

The primary duty of a queen was to secure the succession by producing an heir as soon as she possibly could. Henry still had his older brother, Robert, to contend with and an heir would certainly strengthen his position. By September 1103, Matilda of Scotland had fulfilled this duty by giving birth to a daughter, Matilda, in February 1102, and the much-desired son and heir, William, known as William Ætheling in an allusion to his descent from the Anglo-Saxon royal line, in September 1103. It is possible third child was either stillborn or short-lived. After the births of the royal children, the king and queen appear to have lived separately, with Queen Matilda establishing herself at Westminster. It was rumoured that the queen had chosen a life of celibacy once her duties of producing an heir had been fulfilled.

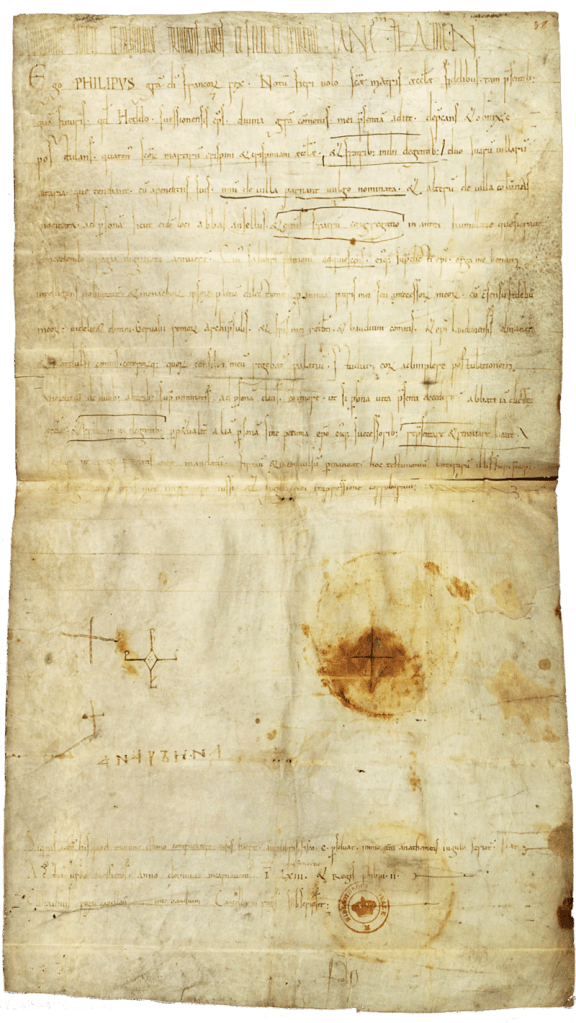

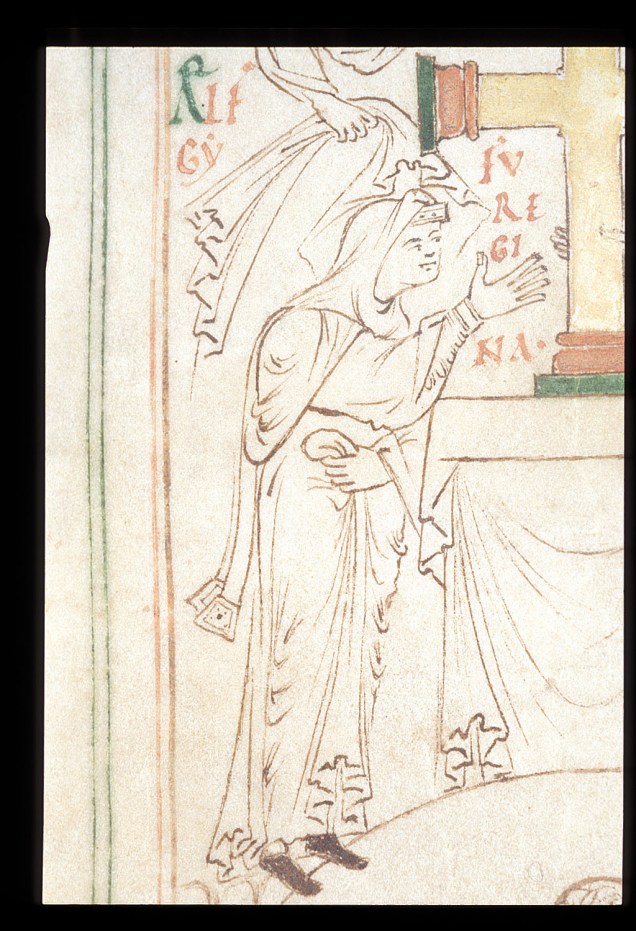

Disputes with Normandy were to be a feature of the first half of Henry’s reign, even after the capture of his brother, Robert at the Battle of Tinchebrai in 1106. Robert would spend the rest of his life imprisoned in England, but his son, William Clito, would later take up the fight. And while Henry subjugated Normandy, Queen Matilda remained in England, often chairing meetings of the king’s council during his absence. The queen had her own seal, which she appended to her charters and which depicted her ‘standing, crowned and wearing a long embroidered robe which falls in folds over her feet. Over this is a seamless mantle which has an embroidered border and is draped over her head. It is fastened at her throat by a brooch, and falls in folds over her arms. In her right hand she holds a sceptre surmounted by a dove, and in her left an orb surmounted by a cross.’.12

As queen, Matilda had received a generous dower settlement, which had been granted from those lands once held by Edith, Edward the Confessor’s queen. Surviving charters issued by Matilda show that she controlled the abbeys of Waltham, Barking and Malmesbury. She held further territory in Rutland and property in London including the wharf later known as Queenhithe, and she also received the tolls of Exeter. Her staff included two clerks who would eventually become bishops. The queen appears to have had a personal interest in managing her estates. In the charter granting Waltham Abbey to his wife, Henry mentions the ‘queen’s court’ held there. Among the queen’s many good works were the building of bridges in Surrey and Essex and the construction of a public bathhouse at Queenhithe. Working with Anselm, Archbishop of Canterbury, Queen Matilda founded a house for the Augustinian canons, Holy Trinity, at Aldgate in London. She also founded a leper hospital at St Giles, funded by sixty shillings a year from dock revenues at her wharf.

Leprosy and the care of lepers was of great concern to the queen. In addition to St Giles, she was the benefactress of a leper hospital at Chichester. Indeed, the queen’s brother David – later David I, King of Scots – told a tale in which he witnessed his sister administering to lepers in her own apartments in Westminster:

The place was full of lepers and there was the Queen standing in the middle of them. And taking off a linen cloth she had wrapped around her waist, she put it into a water basin and began to wash and dry their feet and kiss them most devotedly while she was bathing them and drying them with her hands. And I said to her ‘My Lady! What are you doing? Surely if the King knew about this he would never deign to kiss you with his lips after you had been polluted by the putrefied feet of lepers!’ Then she, under a smile, said ‘Who does not know that the feet of the Eternal King are to be preferred over the lips of a King who is going to die? Surely for that reason I called you, dearest brother, so that you might learn such works from my example.13

While this story may not be an exact recollection of the siblings’ conversation, it does serve to demonstrate the extent of Matilda’s piety, something she inherited from her sainted mother, Queen Margaret. The queen’s piety and interest in religion are evidenced in her surviving correspondence, which involved not only Archbishop Anselm but also leading church figures such as Pope Paschal II, Hildebert of Lavardin, Archbishop of Tours, Herbert of Losinga, Bishop of Norwich and Ivo, Bishop of Chartres. Though written by a clerk rather than in her own hand, these letters are the earliest surviving examples from an English queen.

Matilda and Anselm appear to have had a good working relationship, which is evidenced by her actions as mediator during the Investiture Controversy, which sought to clarify the rules of investiture within the church. In their correspondence, the archbishop wrote to Matilda as his ‘dearest Lady and daughter Matilda, Queen of the English’.14 Likewise, Matilda witnessed a charter at Rochester, prior to Anselm’s exile, as ‘Matildis reginae et filiae Anselmi archiepiscopi’ (Queen Matilda and daughter of Archbishop Anselm).15 And when Anselm was exiled from England from 1103, Queen Matilda acted as mediator between the archbishop, the king and the pope, Paschal II.

The queen appears to have been well aware of her influence over the king, and its limitations. When Henry appropriated the revenues of Canterbury for himself, claiming it was a vacant see with the archbishop in exile, Matilda persuaded him to set aside a personal allowance for Anselm. However, when she was asked to intervene with the king a few years later, when he was attempting to extract more money from the clergy, Matilda ‘wept and insisted she could do nothing’.16 In 1104, Matilda even approached Pope Paschal II, asking for his intervention in the disagreement between Henry and Anselm.

Henry saw the investiture crisis as an erosion of his royal prerogative, and he was determined to cede no ground. But, with the pope threatening excommunication and Matilda voicing her own pleas to her husband, a compromise was eventually reached by which Henry would relinquish his powers to invest prelates but retain the right to receive homage for ‘temporalities’; this latter concession by the church would augment the secular powers of the crown. When Anselm was finally able to return home to England, in 1106, Matilda was there to personally welcome him back from his three-year exile. She then rode in advance of the archbishop, to ensure accommodation and welcoming ceremonies were in place along his route.

The Investiture Controversy served to demonstrate the extent to which Matilda’s influence could be exerted, not only on the king but internationally, through her correspondence with the church’s most powerful prelates. Matilda also acted as regent for Henry when he was away in Normandy, which was more than half of the time. A woman fulfilling such a role in her lord’s absence was far from unusual and indeed was accepted by the barony of the kingdom; Matilda’s daughter, Empress Matilda, would discover that a woman fulfilling this role on her own behalf faced far more resistance. Queen Matilda acted as regent for months at a time, most notably for ten-month spells from September 1114 and from April 1116. In her final regency Matilda was assisted by her only son, the teenage William Ætheling, who was now earnestly in training for his future role as King of England. He would later join his father in Normandy to continue his apprenticeship, fighting in his first battle there in 1119.

Another notable element of queenship was patronage. Queen Matilda commissioned William of Malmesbury to write the Gesta Regum Anglorum, a genealogical history of the royal house of Wessex which was finished after her death and presented to her daughter, Empress Matilda. She also commissioned a biography of her mother, The Life of St Margaret Queen of Scotland by Turgot, Prior of Durham and later Bishop of St Andrew’s, who had been her mother’s confessor. In 1111 the queen attended the ceremony for the translation of St Æthelwold’s relics at Winchester, and the following year she was in Gloucester to witness the presentation of gifts to the monks there.

Matilda was also concerned with justice and in 1116 ordered the release of Bricstan of Chatteris, a prisoner who had apparently been unjustly condemned. Bricstan, who had intended to take holy orders before his arrest – the reason for which is unknown – called upon St Benedict and St Etheldreda for assistance. The two saints are said to have torn his chains from him. The shocked guards immediately turned to Queen Matilda, who ordered an investigation into the events. Satisfied that a miracle had occurred, the queen ordered Bricstans’s immediate release. She also ordered that special masses should be heard, and the bells of London should be rung in celebration.

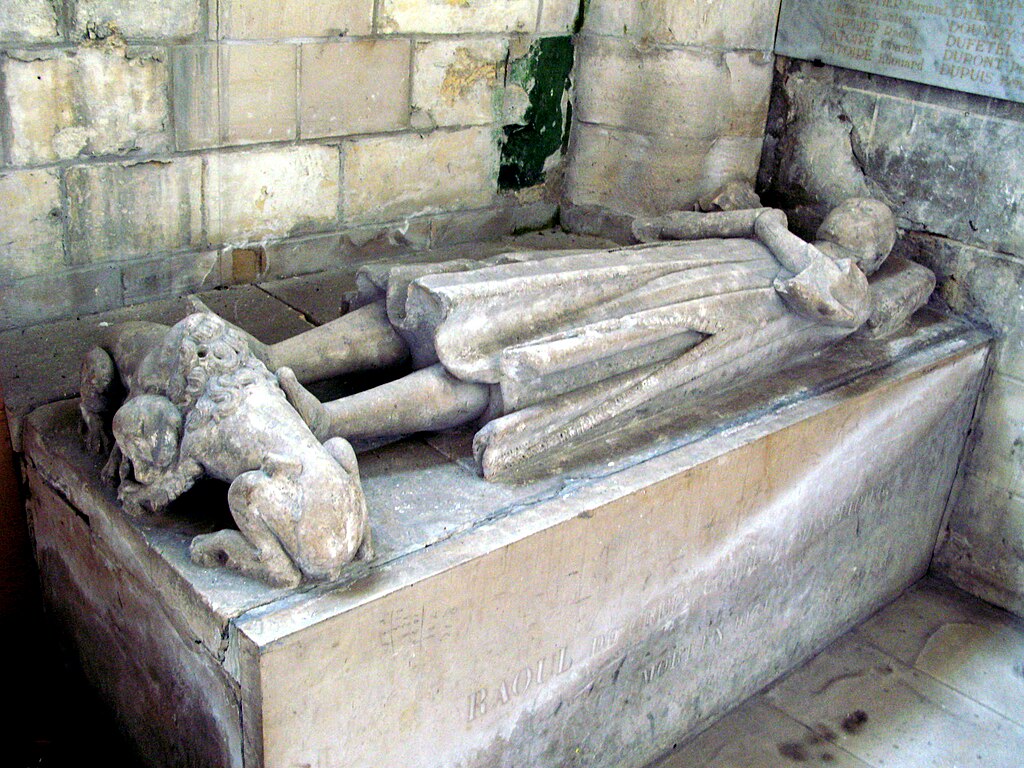

Matilda of Scotland died on 1 May 1118 at Westminster, at the age of thirty-seven. King Henry was in Normandy at the time and Matilda was acting as regent, which suggests that her death was unexpected, though we do not know the cause. The canons of her foundation of Holy Trinity at Aldgate and the monks at Westminster both claimed the right to bury her. She was buried in Westminster Abbey, much to the chagrin of the monks of Aldgate who lodged a complaint with Henry on his return. Henry compensated the order with a gift of relics from the Byzantine emperor. He also confirmed his queen’s donations to Holy Trinity, Aldgate. The king gave money so that a perpetual light could be maintained at her tomb; this was still being paid in the reign of Henry III, Matilda’s great-great-grandson.

Matilda died a beloved queen, and was remembered as ‘Mold the Good Queen’ or ‘Good Queen Maud’. Praise for the queen is almost universal, although William of Malmesbury criticised her for patronising foreigners and reported that she ‘fell into the error of prodigal givers; bringing many claims to her tenantry, exposing them to injuries and taking away their property, but since she became known as a liberal benefactress, she scarcely regarded their outrage’.17

The Warenne Chronicle recorded her death with a fitting epitaph:

So then, almost all of England’s bishops, magnates, abbots, priors, and indeed the innumerable common masses assembled with great sadness for her crowded funeral, and with many tears they attended her burial … I can sum up her praise in this brief declaration that from the time when England was first subject to kings, of all queens none was found like her, nor will a similar queen be found in coming ages whose memory will be held in praise and whose name will be blessed for centuries. So great was the sorrow at her absence and so great a devotion filled everyone, that several of the noblest clerics, whom she had much esteemed in life, stayed at her tomb for thirty days in vigils, prayers and fasting, and they kept mournful and devoted watch…18

A woman of proven ability in governing the kingdom, Queen Matilda served as an example of what a woman could do, and the power she could wield, albeit in her husband’s name.

*

Notes:

1. Lisa Hilton, Queens Consort: England’s Medieval Queens; 2. Eadmer of Canterbury, Historia Novorum in Anglia; 3. Hilton, Queens Consort; 4. ibid; 5. Michael Swanton (ed.), The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles; 6. Ordericus Vitalis, Histoire de Normandie, quatrième partie (my translation); 7. Anselm, quoted in Hilton, Queens Consort; 8. Eadmer, Historia Novorum in Anglia; 9. Hilton, Queens Consort; 10. Eadmer, Historia Novorum in Anglia; 11. ibid; 12. Susan M. Johns, Noblewomen, Aristocracy and Power in the Twelfth-Century Anglo-Norman Realm; 13. Ailred of Rievaulx, quoted in Hilton, Queens Consort; 14. epistolae.ccnmtl.columbia.edu; 15. Hilton, Queens Consort; 16. ibid; 17. William of Malmesbury, quoted in Hilton, Queens Consort; 18. Van Houts and Love, The Warenne (Hyde) Chronicle

Images:

Courtesy of Wikipedia except Henry I, which is ©2025 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS

Sources:

Lisa Hilton, Queens Consort: England’s Medieval Queens; Eadmer of Canterbury, Historia Novorum in Anglia; Michael Swanton (ed.), The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles; Ordericus Vitalis, Histoire de Normandie; Susan M. Johns, Noblewomen, Aristocracy and Power in the Twelfth-Century Anglo-Norman Realm; epistolae.ccnmtl.columbia.edu; Teresa Cole, After the Conquest: The Divided Realm; Jeffrey James, The Bastard’s Sons: Robert, William and Henry of Normandy; Henry of Huntingdon, The History of the English People 1000-1154; Charles Spencer, The White Ship: Conquest, Anarchy and the Wrecking of Henry I’s Dream; E. Norton, England’s Queens: From Boudicca to Elizabeth of York; Nigel Tranter, The Story of Scotland; Elisabeth Van Houts, and Rosalind C. Love (eds and trans), The Warenne (Hyde) Chronicle; Oxford Dictionary of National Biography; Ordericus Vitalis, The Ecclesiastical History of Orderic Vitalis, 1075-1143; J. F. Andrews, Lost Heirs of the Medieval Crown: The Kings and Queens Who Never Were; Anne Crawford (ed.), Letters of the Queens of England; Elizabeth Norton, England’s Queens: From Boudicca to Elizabeth of York; Lida Sophia Townsley, ‘Twelfth-century English queens: charters and authority’, academia.edu;

*

My Books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

Out now: Scotland’s Medieval Queens

Scotland’s history is dramatic, violent and bloody. Being England’s northern neighbour has never been easy. Scotland’s queens have had to deal with war, murder, imprisonment, political rivalries and open betrayal. They have loved and lost, raised kings and queens, ruled and died for Scotland. From St Margaret, who became one of the patron saints of Scotland, to Elizabeth de Burgh and the dramatic story of the Scottish Wars of Independence, to the love story and tragedy of Joan Beaufort, to Margaret of Denmark and the dawn of the Renaissance, Scotland’s Medieval Queens have seen it all. This is the story of Scotland through their eyes.

‘Scotland’s Medieval Queens gives a thorough grounding in the history of the women who ruled Scotland at the side of its kings, often in the shadows, but just as interesting in their lives beyond the spotlight. It’s not a subject that has been widely covered, and Sharon is a pioneer in bringing that information into accessible history.’ Elizabeth Chadwick (New York Times bestselling author)

Available now from Amazon and Pen and Sword Books

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. Heroines of the Tudor World is now available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how Empress Matilda and Matilda of Boulogne, unable to wield a sword themselves, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It shows how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other. Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org. Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell and Elizabeth Chadwick, and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

There are now over 70 episodes to listen to!

Every episode is also now available on YouTube.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter, Threads, Bluesky and Instagram.

*

©2025 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS