Time for another edition of Wordly Women! It has been great fun, meeting all these amazing authors. I do hope everyone is enjoying it as much as I am. Today, I want to introduce you to a very dear friend, historical novelist Cathie Dunn. Cathie and I have known each other a good few years on Facebook, so much so that the first time we met in real life, there was no awkwardness. I love that about social media!

So, let me introduce you to Cathie!

Sharon: Hi, Cathie, first things first, what got you into writing?

Cathie: Ooh, that takes me back decades! It was the romantic historical novels by the likes of M.M. Kaye, Victoria Holt / Philippa Carr (Eleanor Burford’s pseudonyms), in my late teens that got me hooked. I loved Ms Holt’s gothic romance novels in particular, at the time. They were so atmospheric, and – growing up in Germany – I loved the vision of historic and haunted English manors. During the late 1990s and 2000s, after my move to the UK, I learnt a lot about how to create a compelling plot, within a realistic historical setting, by devouring novels by Helen Hollick, Elizabeth Chadwick, and Barbara Wood, amongst others. It was enough to make me embark on HE Certificate in Creative Writing (online) at Lancaster University (though at the time, I was the only one on the course who wrote historical fiction). But at least, it provided me with deeper insights into the writing craft.

Sharon: Tell us about your books.

Cathie: I started off with a project which went from romance to murder mystery to spy novel to (supposedly) a series of events set during the Anarchy – one of my favourite eras. To date, Dark Deceit is an undefined mix, which I’ll need to untangle at some point in time.

Sharon: Yes please! I want to read it!

Cathie: In 2009, I took part in NaNoWriMo, working on a Scottish romance set after the 1715 Jacobite rebellion. I used real locations and studied the background history in depth – too much for traditional romance publishers, who duly rejected it. Fortunately, Highland Arms was picked up by a fabulous US indie press, and my path was clear! I later wrote a second Scottish romance, A Highland Captive, set during the Wars of Independence.

After my move from Scotland to France, my focus changed to medieval French history, with a dual-timeline mystery inspired by my surroundings. Love Lost in Time delves into the distant past of the county of Carcassonne. And the novel immortalised a young cat I lost too soon, Shadow.

Next, I wrote a novel set at the court of Louis XIV. The Shadows of Versailles deals with a dark side of the otherwise glittering court: the Affair of the Poisons. It may be too dark for some readers, as it contains disturbing scenes of child abductions and black masses. Tragically, it’s all based on real, credible accounts of the time. Researching history can be revolting, at times.

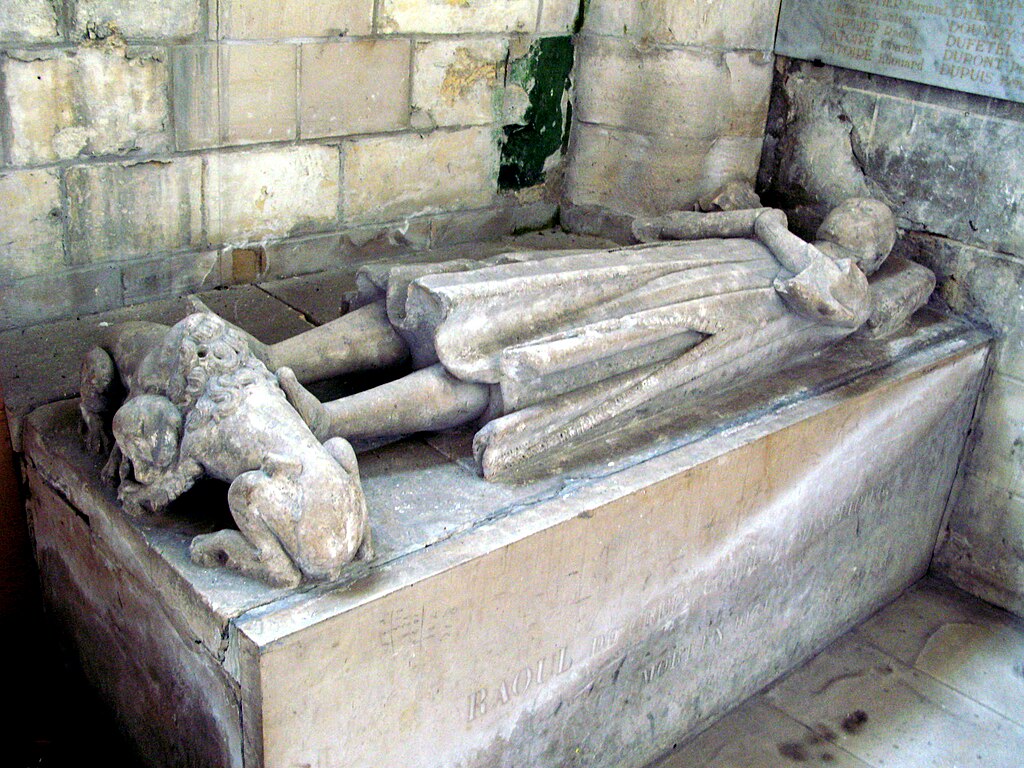

After that serious topic, I needed a more positive distraction, and I promptly delved into the foundation years of Normandy, a county I love. Ascent tells the forgotten story of Poppa of Bayeux. Everyone with a TV now knows her more danico husband – Rollo – but who was the mother of his children? Sadly, she was overlooked in the recent series, Vikings. Ascent tells her (fictionalised) story.

Sharon: What attracts you to the early medieval period?

Cathie: It was an era of great change, all across the British Isles and the European continent. The old ways and beliefs had been discarded, to make way for a Church growing in political influence, and it all makes for fascinating research. New hierarchies were formed amidst a continuing power struggle between different families. As the appointments of ‘nobility’ grew into fashion, so did the influence of favourites and allies on rulers. It was a fascinating time.

Sharon: Who is your favourite early medieval character and why?

Cathie: Ooh, that’s a tricky one. There are so many real people we know little about, especially women.

(So, a big *Thank You* to you for shining a light on them with your brilliant books!)

I do think Poppa of Bayeux deserves a lot more credit. She had to deal with so many challenges – married to a marauding stranger who was likely a decade or two older, and a Pagan; bearing his children; fleeing with him to Anglia; returning to see his power increase, while she is quietly forgotten. I quite like her to be my favourite early medieval character.

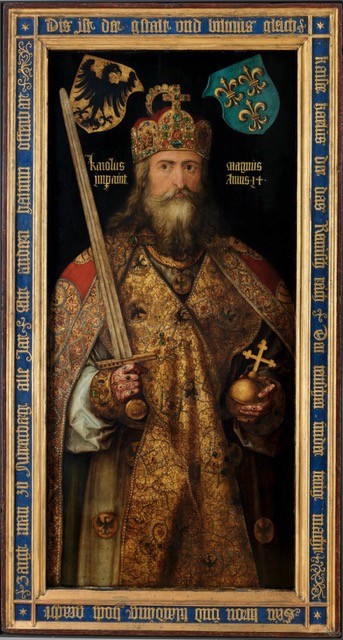

Charles Martel is another. He was a fascinating man, paving the way for a greater Frankish kingdom with his conquests across what is now France. Whilst most people know his grandson, Charlemagne, without Charles, Charlemagne’s ascent in the political sphere of central Europe would not have been possible. Was Charles likeable? Hm, I’m not sure. We know he was ruthless, efficient, and a capable leader of men. Did he have time to be nice? Perhaps that’s a question for another writing project…

Sharon: Who is your least favourite early medieval character and why?

Cathie: That would probably be Charles the Fat, Carolingian King of the Franks and Holy Roman Emperor for a few years in the 880s. He was ineffective, and hopeless at controlling different sections of his empire. He was deposed and died in early 888, and the crown went to Odo of Paris. The Carolingian dynasty was restored after Odo’s reign, though the crown of Frankia went back and forth for a while. This is the era Ascent is set in, and it made for intriguing research.

The real Rollo surely had his work cut out, having to deal with all these changing rulers and their agendas.

Sharon: How do you approach researching your topic?

Cathie: I love history books. I think by now I own more history books than novels! Usually, I start with checking online resources. Jstor is a useful site, where you can read a number of articles for free each month; Medievalists.net is another helpful resource.

But most online sites just give you only an overview, so you need to check books that focus on the relevant era. I have an array of history books on early, high & late medieval England, Tudor England, and medieval & Jacobite Scotland on my shelves. For my France-based novels, I consult non-fiction books in French, many of which I find (handily!) in second-hand bookshops. I also use German resources, where needed.

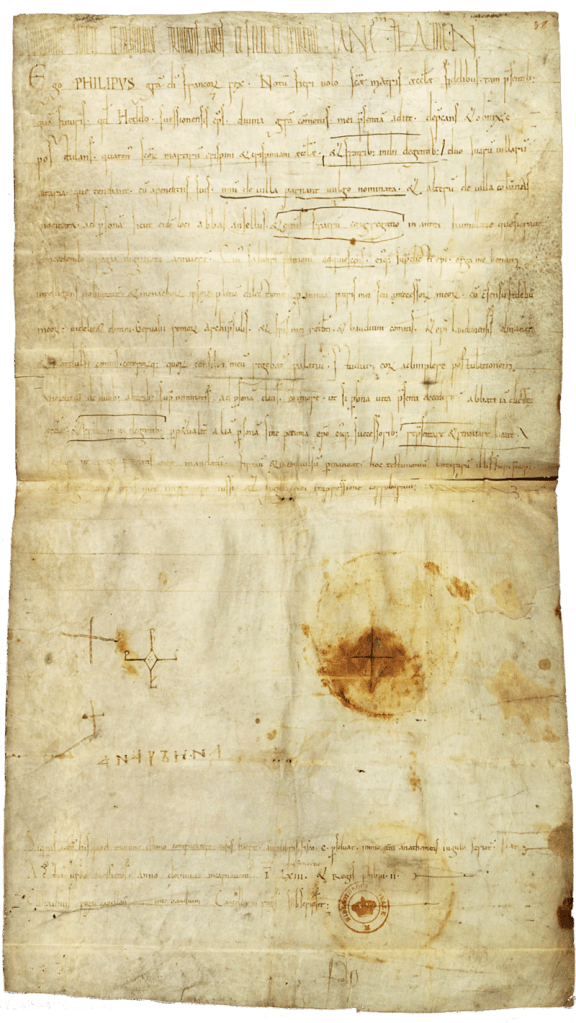

I find that having a range of resources from different countries to consult is the best way to get a fair overview of historic events. We know that original sources were often (though not always) based on what rulers wanted the rest of the world to know – that being not necessarily the full truth. The winner records history in his favour. So, drawing from sources in different languages adds to the experience in discovering the past.

Sharon: That is so true!

Sharon: Tell us your ‘favourite’ medieval story you have come across in your research.

Cathie: Unfortunately, it is difficult to find credible stories about early medieval characters, unless they were major players like Charlemagne, due to the loss (or deliberate omission) of references for lesser-known individuals.

Therefore, I’ve chosen Charlemagne’s wives and concubines as a story I find entertaining, and enlightening! I mean – how on earth did the man have the time to marry four times, have several concubines after the death of his last wife (and possibly before) – and father an estimated twenty (20!) children? His court was always travelling across his ever-expanding realm (and later, his empire), though it is said that his main seat at Aachen (Aix-la-Chapelle) became his favourite.

He insisted his illegitimate children were raised alongside his legitimate offspring, ensuring they all received an education deserving of their Royal bloodline. After his son Pepin’s untimely death, he even took his grandchildren in to be educated with the others.

This is a fact I recently discovered, and now I’m curious to find out more! With daughters, and especially illegitimate ones, usually being swept off into marriage or convents, his insistence that they are all educated is telling. Clearly, here was a man who valued learning – be that in practical skills or reading and writing.

For a man who ruthlessly expanded his territories, responsible for subjugation of peoples and a great number of deaths ranging from Germanic Saxony to the Iberian Peninsula, this shows an entirely different side of the ‘great Charles’.

Sharon: Tell us your least ‘favourite’ medieval story you have come across in your research.

Cathie: That has to be Charlemagne’s darkest episode – the subjugation of Germanic Pagan tribes in Saxony. The wars lasted – on and off – for three decades, and they were brutal. The Saxons did not give in easily, much to Charlemagne’s frustration, and their conversion to Christianity was slow. Their skirmishes into his territory vexed him immensely.

Eventually, according to the Royal Frankish Annals, the infamous ‘Blood Court’ massacre at Verden, in October 882, saw the execution of approx. 4,500 Saxon ‘rebels’ captured after recent battles. Their leader, Widukind, had managed to flee north.

Although later historians disputed the figure quoted in the annals, with several trying to make ridiculous excuses for Charlemagne’s actions, there seems to have been a great slaughter of thousands of prisoners, regardless. Charlemagne wanted to set an example, an effective deterrent.

Warfare continued for three more years, then it was all over for the Saxons, especially after Widukind converted to Christianity. But it was the massacre at Verden that remained like a blood stain on his otherwise pristine reputation.

Sharon: Are there any other eras you would like to write about?

Cathie: I do love different eras, as you know. The Anarchy is definitely high on my list, and I’ll have to revisit Dark Deceit to see where it takes me. (Sharon: Do it! Please!)

But I also love the court of Louis XIV of France, with all its superficial splendour and dark secret plots. The Affair of the Poisons is such an intriguing event, with many prolific nobles implicated in trying to influence the king’s opinion through nefarious deeds. Deeply disturbing, and utterly fascinating.

And then, of course, is the time of the Scottish Wars of Independence. It wasn’t easy to mess with a remarkable, power-hungry king like Edward I! (Sharon: Ooh, yes!)

But, ultimately, it’s the late Dark Ages (do we still call it that, as they weren’t really that dark?) and early Middle Ages that keep me hooked. Oh, to travel to Frankia for one day only…

Sharon: What are you working on now?

Cathie: My current WIP is called Treachery, and it’s the story of Sprota the Breton, handfasted wife of William Longsword – Poppa’s and Rollo’s son. Like his father and his two wives, William married Sprota in more danico (in the Danish custom), and Luitgarde of Vermandois in a proper Church blessing, for political reasons.

Even less is known of Sprota than of Poppa; mainly that she was mother to William’s only son, Richard, likely the first Duke of Normandy. (Rollo and William never were dukes.) I introduced her towards the end of Ascent, when she had to flee to Bayeux as William’s enemies closed in on him at his fortress in Fécamp. Following William’s assassination by Count Arnulf of Flanders in 842, Sprota had to remarry to keep her young son’s inheritance secure. And to ensure his safety!

Her responsibility as the mother of William’s heir, and her struggles for them to survive, make for an intriguing story. So many powerful men had set their sights on Normandy, wanting Richard out of the way. I hope to do Sprota justice, as, again, she has been forgotten in time.

The third and final instalment of my House of Normandy trilogy about the early ladies of Normandy will conclude in Reign, about Richard’s second wife (and previous lover), Gunnora.

Then there’s Poppa’s daughter Adela, married to the Count of Poitou. Perhaps a companion novel? 😉 Sigh…

Sharon: And finally, what is the best thing about being a writer?

Cathie: Exploring past histories is utterly fascinating, and I can only recommend it. That goes for the good and the bad we discover in our research.

Reliving the distant past is fun, but also a great responsibility, as we should stay as close to the few known facts as possible. An ogre can’t just turn into a Prince Charming, although looking at Charlemagne, he definitely had two sides to his character – the caring father interested in learning and culture, and ruthless ruler chopping off heads of his prisoners. A man of his times. But what about his women? (Cathie, behave! One novel at a time…)

And though my earlier works focused more on events and fictional characters, I now find it far more rewarding to bring forgotten women from the distant past back to life, even ‘just’ in fictionalised format. Their stories must be told.

Thank you again for letting me ramble on about my research and writing. It’s been fabulous revisiting my stories, and the real characters involved in them, and I hope your readers enjoy my interview.

Sharon: Cathie, thank you so much! It has been a pleasure! No wonder you and I get on so well!

About the Author:

Cathie Dunn is an Amazon-bestselling author of historical fiction, dual-timeline, mystery, and romance. She loves to infuse her stories with a strong sense of place and time, combined with a dark secret or mystery – and a touch of romance. Often, you can find her deep down the rabbit hole of historical research…

In addition, she is also a historical fiction book promoter with The Coffee Pot Book Club, a novel-writing tutor, and a keen book reviewer on her blog, Ruins & Reading.

After having lived in Scotland for almost two decades, Cathie is now enjoying the sunshine in the south of France with her husband, and her rescued pets, Ellie Dog & Charlie Cat.

She is a member of the Historical Novel Society, the Richard III Society, the Alliance of Independent Authors, and the Romantic Novelists’ Association.

Where to find Cathie:

Website: Amazon; Facebook Author Page; Twitter / X; Bluesky.

To Buy Cathie’s books: Ascent: Love Lost in Time

*

My Books:

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

Out now: Scotland’s Medieval Queens

Scotland’s history is dramatic, violent and bloody. Being England’s northern neighbour has never been easy. Scotland’s queens have had to deal with war, murder, imprisonment, political rivalries and open betrayal. They have loved and lost, raised kings and queens, ruled and died for Scotland. From St Margaret, who became one of the patron saints of Scotland, to Elizabeth de Burgh and the dramatic story of the Scottish Wars of Independence, to the love story and tragedy of Joan Beaufort, to Margaret of Denmark and the dawn of the Renaissance, Scotland’s Medieval Queens have seen it all. This is the story of Scotland through their eyes.

‘Scotland’s Medieval Queens gives a thorough grounding in the history of the women who ruled Scotland at the side of its kings, often in the shadows, but just as interesting in their lives beyond the spotlight. It’s not a subject that has been widely covered, and Sharon is a pioneer in bringing that information into accessible history.’ Elizabeth Chadwick (New York Times bestselling author)

Available now from Amazon and Pen and Sword Books

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. Heroines of the Tudor World is now available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how Empress Matilda and Matilda of Boulogne, unable to wield a sword themselves, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It shows how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other. Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org. Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

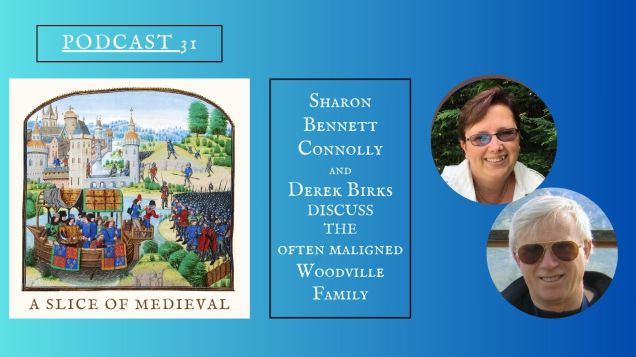

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell and Elizabeth Chadwick, and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

Every episode is also now available on YouTube.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter, Threads, Bluesky and Instagram.

*

©2025 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS and Cathie Dunn