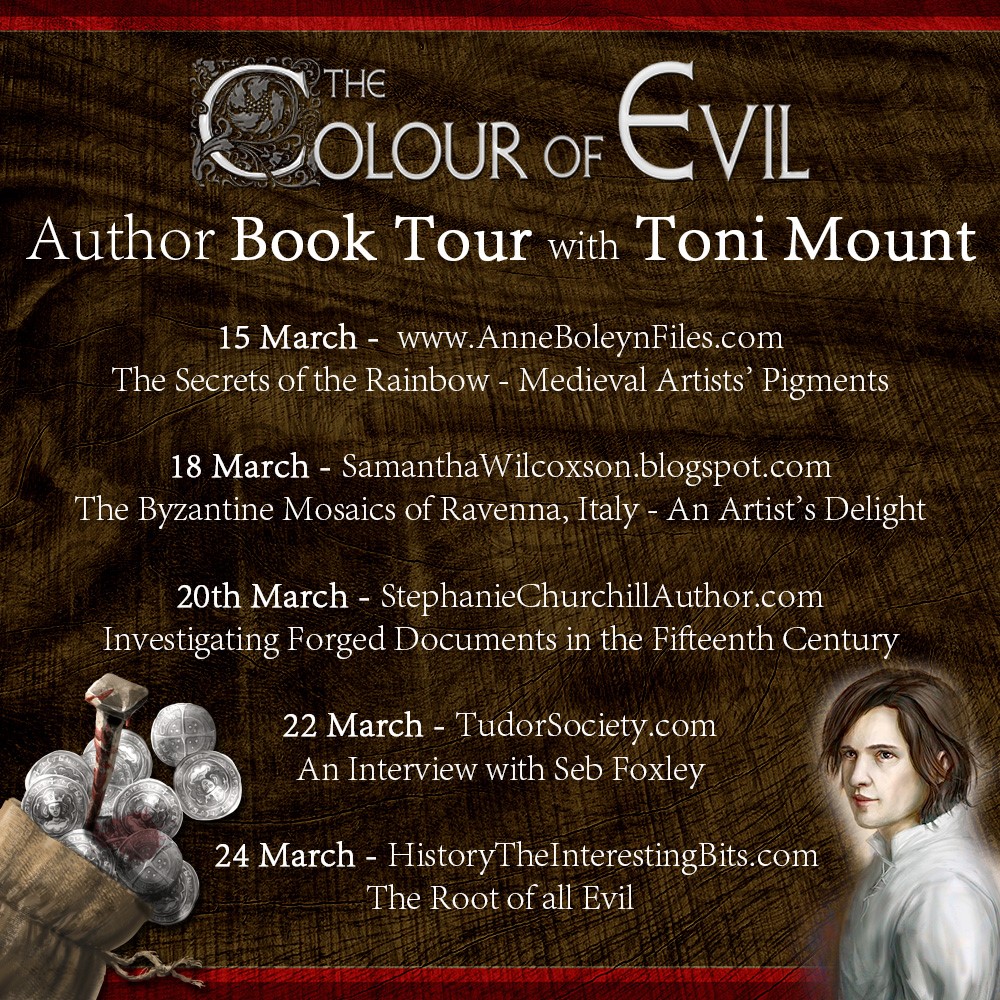

Today it is a pleasure to welcome author and historian Toni Mount to the blog, as part of Toni’s blog tour for her fabulous new novel, The Colour of Evil, which is released on 25th March.

The Root of all Evil – Money to spend in Medieval London

The theme in my latest novel in the The Colour of … series is money, whether earning it, owing it, forging it or even murdering because of it. Our hero, Seb Foxley, has to solve the mysteries, however he can. So I thought an article about medieval money might interest readers.

From Anglo-Saxon times, England’s currency system was based on the penny which contained one pennyworth of silver. These were minted from high quality ‘sterling’ silver, so called because the earliest coins were known as steorlings or little stars; perhaps a star was part of the original design. By the time of William the Conqueror [1066-86] a pounds worth of starlings was accepted as well-respected money across Europe. However, not all Kings of England took care to keep constant the value of silver in a penny. Henry I’s reign was a particularly bad time for the coinage and in 1124 the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recorded that ‘pennies were so adulterated, a pound at market could not purchase twelve pence worth of anything’. Since 12 pence = 1 shilling and 20 shillings = £1, this meant a penny wasn’t worth one-twentieth of its original value back in 1066. The reign of King Stephen [1135-54] didn’t help as it was a period of almost constant civil war. In fact, things became worse because different factions set up their own mints and coins became mere tokens, often spendable only within the jurisdiction of a particular faction. Somebody had to sort out the mess.

Fortunately for the reputation of England’s monetary system, Henry Plantagenet became King Henry II in 1154 and from 1158 he issued an entirely new set of currency, asserting royal control over just thirty designated mints and restored not only the silver content of the pennies but confidence in English money. And this was a good time to do so because trade across Europe was changing from the barter system, when a dozen eggs could pay for a pair of shoes to be mended, or a day’s work might be repaid with a sack of flour, to the purchase of goods and services using money.

It was easier also to gather taxes and customs duties for the king in coin, rather than in kind, and Henry demanded efficiency in their collection. In fact, the system worked so well in England that when Henry’s son, Richard the Lionheart, was held to ransom in 1192 for the incredible sum of £100,000 [about $17.5 million today], most of it was gathered in England and paid in English pennies, despite Richard’s realm including much of France at the time.

Having put the monetary system in good order, the ‘Trial of the Pyx’ was invented to keep it that way and safeguard the value of new-minted coins. It is thought that this institution began in the twelfth century but in 1282 Edward I made it official and records have been kept ever since. Conducted like a public legal trial, twelve ‘discreet and lawful’ citizens of London and twelve members of the Goldsmiths’ Company sat as a jury to judge the legitimacy of the newly minted coins. Coin samples were taken from every minting and set aside for assay in secure chests called pyx – hence the name of the trial. It’s the same word used for the box in which consecrated bread is kept at Holy Communion, showing the significance of this procedure. For centuries they were stored in the Pyx Chamber in Westminster Abbey, along with other important items belonging to both state and church.

Early trials were held first in Westminster Hall and later in the Exchequer at Westminster, taking place annually. The jury was summoned by and the trial presided over by the King’s [or Queen’s] Remembrancer of the Royal Courts of Justice. The size, weight, silver purity and content of the coins were all examined and verified, the jury passing its verdict on the results. The trial was held at the beginning of the year on the previous year’s samples, allowing two months for the proceedings and a third month for the assayers’ testing and reports before the Remembrancer announced the result of the trial.1

The medieval monetary system of England was complicated, to say the least. As I write this, it’s fifty years since the decimalisation of our coinage in Britain [15th Feb 1971] and our own pre-decimalisation coinage was still based upon the medieval system: 12 pennies [12d] = 1 shilling; 20 shillings [20s] = £1 and, therefore 240 pennies = £1. It made accounting tricky and you had to know your 12 times table. But until 1489, there was no coin of the value of £1 and there were no shilling coins until 1504.

In some ways, to the average carpenter, shoemaker and housewife, this didn’t matter very much because with a skilled man’s wages counted in pennies, the chance of him requiring, handling – or even seeing – a coin of denomination larger than a groat was slim indeed. A groat was a silver coin worth 4 pennies, the word ‘groat’ being a corruption of the French word gros, meaning large because, in 1279, when Edward I first issued it, it was the biggest coin in circulation. 3 groats = 1 shilling but even then a groat was engraved with a design to divide it exactly into four quarters so it could be reduced to 2 half-groats [worth 2d each] or even 4 equal pennyworths of silver. The round 1 penny coins [1d] were similarly engraved so they could be cut into 2 halfpennies and again into 4 farthings [originally ‘fourthings’]. England still used farthings as proper, circular coins, not cut-downs, into the 1950s. These were the coins of everyday use in medieval times.

But there were people who dealt in larger sums than pennies. A medieval merchant’s cargo of wine imported from Bordeaux was going to cost more than a few pence, as would the hire of the ship and the customs duties to be paid. Counting out hundreds of tiny coins, some of them wedge-shaped from being cut down, was a time-consuming business and time – as ever – was money. So it made sense to have some higher value coins in use for such transactions. Pounds and shillings, maybe? No. Nothing so simple as that. The account ledgers might show business conducted in pounds, shillings and pence but the coins changing hands bore little resemblence to what was noted down. A common amount used in both theoretical and practical accounting was the mark.

note the image of the Archangel Michael slaying the devil

The mark had been around since Anglo-Saxon times and had varied in value but, by the fifteenth century, a mark was worth 13s 4d. This may seem an arbitrary amount but is 160 pennies = two-thirds of £1. The half-mark [6s 8d, one-third of £1 or 80 pence] was an actual coin so that three half-marks equalled £1 in total comprised of just three coins that were so much easier to count and handle. There were even quarter-marks worth 3s 4d. This explains the frequent appearance of these values in medieval accounts ledgers. The half-mark was minted in gold and at various times was known as the noble, the rose-noble and the angel – this last after the image of St Michael the Archangel on the reverse. There was also a short-lived gold ryal [or royal] from 1465 worth 10 shillings.

Henry VII was not only determined to refill his empty coffers, by fair means or otherwise – his tax-gatherering methods were notorious – he wanted to be certain the actual coins were worth their face value, so one of the first things he did after becoming king was overhaul the coinage. Firstly, in 1489, he invented the £1 coin, called it a sovereign and had it minted in gold with his own image on the the obverse – a declaration that the Tudor king had arrived, if ever there was one.

The 10 shilling ryal and the 6s 8d angel were both reminted as silver coins, their previously gold counterparts having often been hoarded or melted down into cups, plates and jewellery. Pennies, half-groats [2d] and groats were all redesigned and their silver content assured, as well as the new silver shillings by 1504.

Readers may think that the writing of cheques cannot predate the banking system – the Bank of England was first set up in 1694, although Italian bankers go back centuries before that. Surprisingly, the first ‘cheques’ were invented by ordinary citizens and had nothing to do with banks. Rather, it had to do with keeping heavy valuables safe. In medieval times, people kept their assets in solid form, as gold plate, silver gilt candlesticks, fine goblets, jewellery and even expensive textiles and books. The crown jewels were frequently used as collateral to borrow money by kings in need of ready cash. A wary citizen would want his bulky treasures stored safely where thieves couldn’t help themselves and even the Royal Treasury at Westminster was looted on one occasion in the fourteenth century – the thieves were apprehended in the end but not all the swag was recovered. However, few folk had the facilities for storing their treasures. Important documents were sometimes locked in a chest at the parish church to which only the priest and the churchwarden had keys. But there wasn’t room for stacks of gold plate or suchlike. In London, the Goldsmiths’ Company kept their precious resources in their vaults underneath Goldsmiths’ Hall and were willing to rent out space to others to store their assets. This kept everything secure but what happened when, say, a wealthy merchant wished to use his set of gold plate to purchase a house from a rich widow? Instead of going to the goldsmiths, demanding his plates and then carrying the heavy weight across the city, risking robbery along the way, and handing them to the widow who would probably then have to arrange the plates’ return to the goldsmiths’ for safe-keeping, the cheque was invented. The cheque was simply a written document to inform the goldsmiths that the wealthy merchant’s gold plate stored in their vaults had now been transferred to the property of the rich widow. No physical effort, inconvenience or risks of loss were involved.

No medieval cheques are known to survive but would have looked similar, probably with a red wax seal, as here

In fact, bank notes, invented much later, were simply ready-written cheques made out for specific sums and, in theory at least, like the earlier cheques, could be used to redeem the valuables themselves. Today, Bank of England notes still say in very small print ‘I promise to pay the bearer on demand the sum of five pounds’, or whatever the value, signed on behalf of the Government and Company of the Bank of England by the bank’s Chief Cashier. I wonder what they’d do if I did present my fiver and demand the equivalent in silver or gold? Laugh themselves silly, probably.

Footnote:

1 For more information on the history and the conduct of the Trial of the Pyx in the 21st century see https://www.assayofficelondon.co.uk/about-us/trial-of-the-pyx

*

Huge thanks to Toni for a fantastic article and good luck with the new book. To look back on the rest of the blog tour:

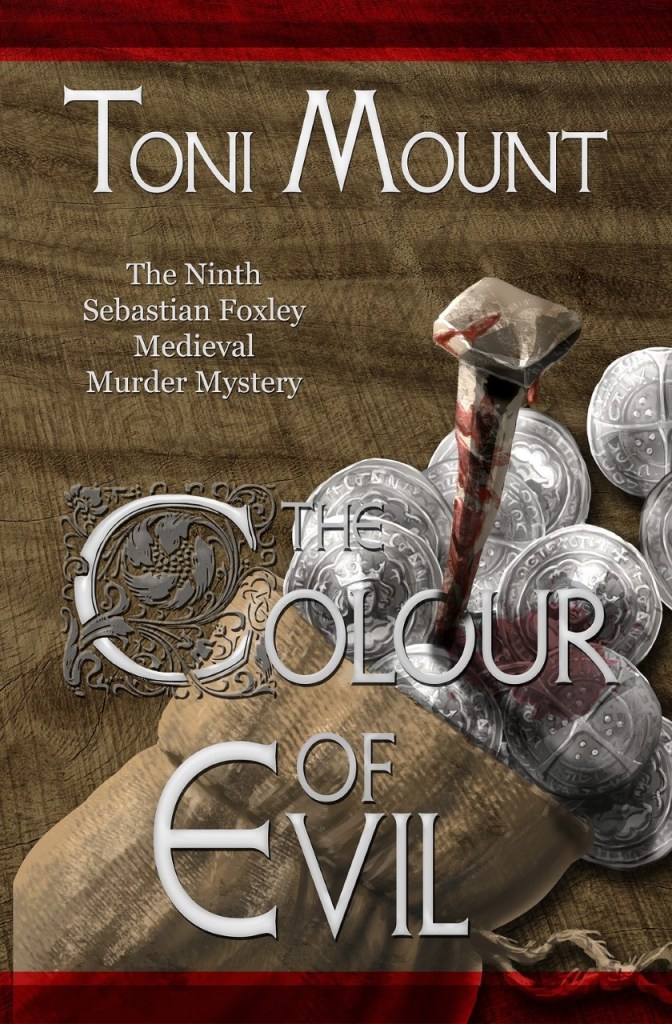

About ‘The Colour of Evil’:

Every Londoner has money worries. Seb Foxley, talented artist and some-time sleuth, is no exception but when fellow indebted craftsmen are found dead in the most horrible circumstances, fears escalate. Only Seb can solve the puzzles that baffle the authorities and help Bailiff Thaddeus Turner to track down and apprehend the villains.

When Seb’s wayward, elder brother, Jude, returns, unannounced, from Italy with a child-bride upon his arm, shock turns to dismay as life becomes more complicated and troubles multiply.

From counterfeit coins to deadly darkness in the worst corners of London, from mysterious thefts to attacks of murderous intent – Seb finds himself embroiled at every turn. With a royal commission to fulfil and heartache to resolve, can our hero win through against the odds?

Share Seb Foxley’s latest adventures in the filthy streets of medieval London, join in the Midsummer festivities and meet his fellow citizens, both the respectable and the villainous.

The Colour of Evil comes out on 25th March.

To buy the Book: http://getbook.at/colour_of_evilhttp://mybook.to/Colour_Evil

About the Author

Toni Mount earned her Master’s Degree by completing original research into a unique 15th-century medical manuscript. She is the author of several successful non-fiction books including the number one bestseller, Everyday Life in Medieval England, which reflects her detailed knowledge in the lives of ordinary people in the Middle Ages. Toni’s enthusiastic understanding of the period allows her to create accurate, atmospheric settings and realistic characters for her Sebastian Foxley medieval murder mysteries. Toni’s first career was as a scientist and this brings an extra dimension to her novels. It also led to her new biography of Sir Isaac Newton. She writes regularly for both The Richard III Society and The Tudor Society and is a major contributor of online courses to MedievalCourses.com. As well as writing, Toni teaches history to adults, coordinates a creative writing group and is a member of the Crime Writers’ Association.

http://www.tonimount.com (my website) http://www.sebastianfoxley.com (Seb’s own website) http://www.facebook.com/sebfoxley (Seb’s Facebook page) http://www.facebook.com/medievalengland (my ‘Medieval England’ Facebook page) http://www.facebook.com/toni.mount.10 (my general Facebook page) http://www.medievalcourses.com (seven of my history courses ‘online’ for download)

*

My books

Coming 31st May:

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, of the successes and failures of one of the most powerful families in England, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III.

Defenders of the Norman Crown: Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey will be released in the UK on 31 May and in the US on 6 August. And it is now available for pre-order from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US and Book Depository.

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available from Pen & Sword, Amazon and from Book Depository worldwide.

Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon and Book Depository.

Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, Book Depository.

*

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

©2021 Sharon Bennett Connolly.

Absolutely b***Dy fascinating! Thank you so much

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Sylvia, I will let Toni now. I can heartily recommend her books, both fiction and non-fiction.

LikeLike

Absolutely fab article – so beautifully simplified. My current novel is set in C14th Italy and the coinage and moneys of account are a nightmare. If there were a Venetian equivalent to this I would have it pinned to my pin board!

LikeLike

Thank you for the coinage education! I have often wondered about it and now I know!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is really interesting. I have to admit I have a special thing for old coins, I’ve seen those cut ones with the cross pop up on metal detecting accounts, and now I know why! And to see that Henry VII sovereign coin is amazing – he definitely sent out a message with that one. Very informative, enjoyed reading this – thanks!

LikeLike