The third surviving son of Edward III and Philippa of Hainault John of Gaunt was born in 1340 at the Abbey of St Bavon, in Ghent in modern-day Belgium. At the height of his career he was the most powerful man in the kingdom after the king. He was virtually regent for his father, Edward III, in his old age, thus getting the blame for military failures and government corruption. His reputation was further damaged when he blocked the reforms of the Good Parliament of 1376, which had tried to curb the corruption of Edward III’s and limit the influence of the king’s grasping mistress, Alice Perrers.

John of Gaunt’s wealth meant he could form the largest baronial retinue of knights and esquires in the country. He alone provided a quarter of the army raised for Richard II’s Scottish campaign in 1385. A stalwart supporter of his nephew, Richard II, he was the target for the rebels during the Peasants’ Revolt; his London residence, the Savoy Palace, was burned to the ground in 1381.

He was a soldier and statesman whose career spanned 6 decades and several countries, including England, Belgium, France, Scotland and Castile. However, by far the most fascinating part of his life is his love life. John married three times; his wives being two great heiresses and a long-time mistress.

John of Gaunt’s first marriage, at the age of 19, was aimed to give him prestige, property and income and was arranged as part of his father’s plans to provide for the futures of several of his children. John and 14-year-old Blanche of Lancaster, youngest daughter of Henry of Grosmont, Duke of Lancaster, were married on 19th May 1359 in the Queen’s Chapel at Reading.

It is quite likely that John had already fathered one child, a daughter, Blanche, by Marie de St Hilaire before his marriage. Blanche was born sometime before 1360 and would go on to marry Sir Thomas Morieux before her death in 1388 or 1389.

Blanche of Lancaster was described as “jone et jolie” – young and pretty – by the chronicler Froisssart, and also “bothe fair and bright” and Nature’s “cheef patron of beautee” by Geoffrey Chaucer. She brought John of Gaunt the earldom of Lancaster following her father’s death from plague in 1361, and those of Leicester and Lincoln when her older sister, Matilda, died of the same disease in 1362, making him the largest landowner in the country, after the king.

The marriage proved very successful, with 7 children being born in just 8 years, 3 of whom survived infancy; daughters Philippa and Elizabeth and a son, Henry of Bolingbroke.

It has always been believed that Blanche died in 1369, when John of Gaunt was away in France, having moved her young family to Bolingbroke Castle in Lincolnshire, to escape a fresh outbreak of the Black Death, but that she succumbed to the plague while there. However, recent research has discovered that Blanche died at Tutbury on 12th September, 1368, more likely from the complications of childbirth than from the plague, following the birth of her daughter, Isabella, who died young. Her husband was by her side when she died and arranged to have prayers said for the soul of his lost duchess.

She was buried in St Paul’s Cathedral in London. John of Gaunt arranged for a splendid alabaster tomb and annual commemorations for the rest of his life. John also commissioned Geoffrey Chaucer to write The Book of the Duchess, also known as The Deth of Blaunche; a poem that is said to depict Gaunt’s mourning for his wife, in the tale of a Knight grieving for his lost love. In it Chaucer describes Blanche as “whyt, smothe, streght and flat. Naming the heroine “White”, he goes on to say she is “rody, fresh and lyvely hewed”.

Before 1365 Blanche had taken into her household a lady called Katherine Swynford, wife of one of her husband’s Lincolnshire knights. John was godfather to the Swynfords’ daughter, Blanche. Katherine later became governess to Blanche’s two daughters, Philippa and Elizabeth and young Blanche Swynford was lodged in the same chambers as the Duchess’s daughters, and accorded the same luxuries as the princesses.

Katherine was the daughter of a Hainault knight, Sir Paon de Roet of Guyenne, who came to England in the retinue of Queen Philippa. She had grown up at court with her sister, Philippa, who would later marry Geoffrey Chaucer. Whilst serving in Blanche’s household, she had married one of John of Gaunt’s retainers, a Lincolnshire knight, Sir Hugh Swynford of Coleby and Kettlethorpe, at St Clement Danes Church on the Strand, London.

Following Blanche’s death Katherine stayed on in the Duke’s household, taking charge of the Duke’s daughters. However, it was only shortly after her husband’s death in 1371 that rumours began of a liaison between Katherine and the Duke; although it is possible the affair started before Sir Hugh’s death, this is far from certain.

John and Katherine would have four children. They had 3 sons, John, Thomas and Henry, and a daughter, Joan, in the years between 1371 and 1379. They were supposedly born in John’s castle in Champagne, in France, and were given the name of the castle as their surname; Beaufort. However it seems just as likely that they were named after the lordship of Beaufort, which had formerly belonged to Gaunt and to which he still laid claim.

Meanwhile, John had not yet done with his dynastic ambitions and, despite his relationship with Katherine, married Constance of Castile in September 1371. Constance was the daughter of Peter I “the Cruel” and his ‘hand-fast’ wife, Maria de Padilla. Born in 1354 at Castro Kerez, Castile, she succeeded her father as ‘de jure’ Queen of Castile on 13th March 1369, but John was never able to wrest control of the kingdom from the rival claimant Henry of Tastamara, reigning as Henry III, and would eventually come to an agreement in 1388 where Henry married John and Constance’s daughter, Katherine.

Katherine – or Catalina – was born in 1372/3 at Hertford Castle and was the couple’s only surviving child.

John and Constance’s relationship appears to be purely dynastic. There is some suggestion John formally renounced his relationship with Katherine and reconciled with Constance in June 1381, possibly as a way to recover some popularity during the Peasant’s Revolt, following the destruction of his palace on the Thames.

Katherine left court and settled at her late husband’s manor at Kettlethorpe, before moving to a rented townhouse in Lincoln. John of Gaunt visited her regularly throughout the 1380s, and Katherine was frequently at court. With 4 children by John of Gaunt but still only, officially, governess to his daughters, Katherine was made a Lady of the Garter in 1388.

Constance, however, died on 24th March, 1394, at Leicester Castle and was buried at Newark Abbey in Leicester.

John then went to Guienne to look after his interests as Duke of Aquitaine and remained in France from September 1394 until December 1395. When he returned to England, John wasted no time in reuniting with Katherine and they were married in Lincoln Cathedral in January 1396.

John then made an appeal to the Pope and his children by Katherine were legitimated on 1st September 1396, and then by Charter of Richard II on 9th February 1397. However, it is claimed a later clause excluded the Beaufort children from the succession.

John was a man of renown, of culture and refinement. An amateur poet and friend of Chaucer, who had married Katherine’s sister, Philippa, he was also a patron of Wycliffe and encouraged the translation of the Bible into English.

His complicated love life would cause problems for future generations, with his son by Blanche of Lancaster, Henry, forcing the abdication of Richard II and usurping the throne on 30th September 1399. His Beaufort descendants would be prominent players on both sides of the Wars of the Roses. While his son John, Earl of Somerset was the grandfather of Margaret Beaufort, mother of Henry VII, his daughter, Joan, was grandmother of the Yorkist kings Edward IV and Richard III.

Katherine would outlive John and died at Lincoln on 10th May 1403. She was buried, close to the High Altar, in the cathedral in which she had married her prince just 7 years earlier. Her daughter Joan, Countess of Westmoreland, was laid to rest beside her, following her death in 1440. Their tombs, however, are empty and they are buried beneath the floor of the cathedral.

John himself died on 3 February 1399, probably at Leicester Castle. He was buried in Old St Paul’s Cathedral, beside his first wife, Blanche of Lancaster. This has often been seen as his final act of love for his first wife, despite the problems John went through in order to finally be able to marry his mistress, Katherine Swynford.

Personally, I think the two ladies, Blanche and Katherine, were his true love at different parts of John’s life. And I hope he had some feelings for poor Constance, who frequently appears as only a means to his dynastic ambitions.

*

Article originally published on English Historical Fiction Authors in September 2015.

*

Sources: Williamson, David Brewer’s British Royalty; Juliet Gardiner & Neil Wenborn History Today Companion to British History; Mike Ashley The Mammoth Book of British Kings & Queens; Alison Weir Britain’s Royal Families, the Complete Genealogy; Paul Johnson The Life and Times of Edward III; Ian Mortimer The Perfect King, the Life of Edward III; WM Ormrod The Reign of Edward III; Edited by Elizabeth Hallam Chronicles of the Age of Chivalry; Amy Licence Red Roses: From Blanche of Gaunt to Margaret Beaufort; katherineswynfordsociety.org.uk; womenshistory.about.com/od/medrenqueens/a/Katherine-Swynford;.

*

Pictures courtesy of Wikipedia, except the tomb of Katherine Swynford, © Sharon Bennett Connolly, 2015.

*

My Books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

Out Now! Women of the Anarchy

On the one side is Empress Matilda, or Maud. The sole surviving legitimate child of Henry I, she is fighting for her birthright and that of her children. On the other side is her cousin, Queen Matilda, supporting her husband, King Stephen, and fighting to see her own son inherit the English crown. Both women are granddaughters of St Margaret, Queen of Scotland and descendants of Alfred the Great of Wessex. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how these women, unable to wield a sword, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It show how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other.

Available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK.

Coming on 15 June 2024: Heroines of the Tudor World

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. These are the women who made a difference, who influenced countries, kings and the Reformation. In the era dominated by the Renaissance and Reformation, Heroines of the Tudor World examines the threats and challenges faced by the women of the era, and how they overcame them. Some famous, some infamous, some less well known, including Anne Boleyn, Elizabeth Barton, Catherine de Medici, Bess of Hardwick and Elizabeth I. From writers to regents, from nuns to queens, Heroines of the Tudor World shines the spotlight on the women helped to shape Early Modern Europe.

Heroines of the Tudor World is now available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK.

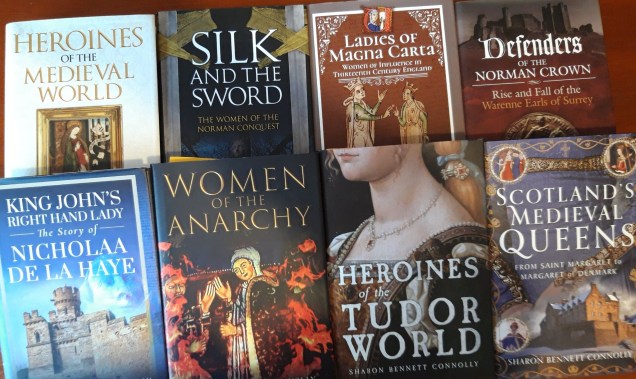

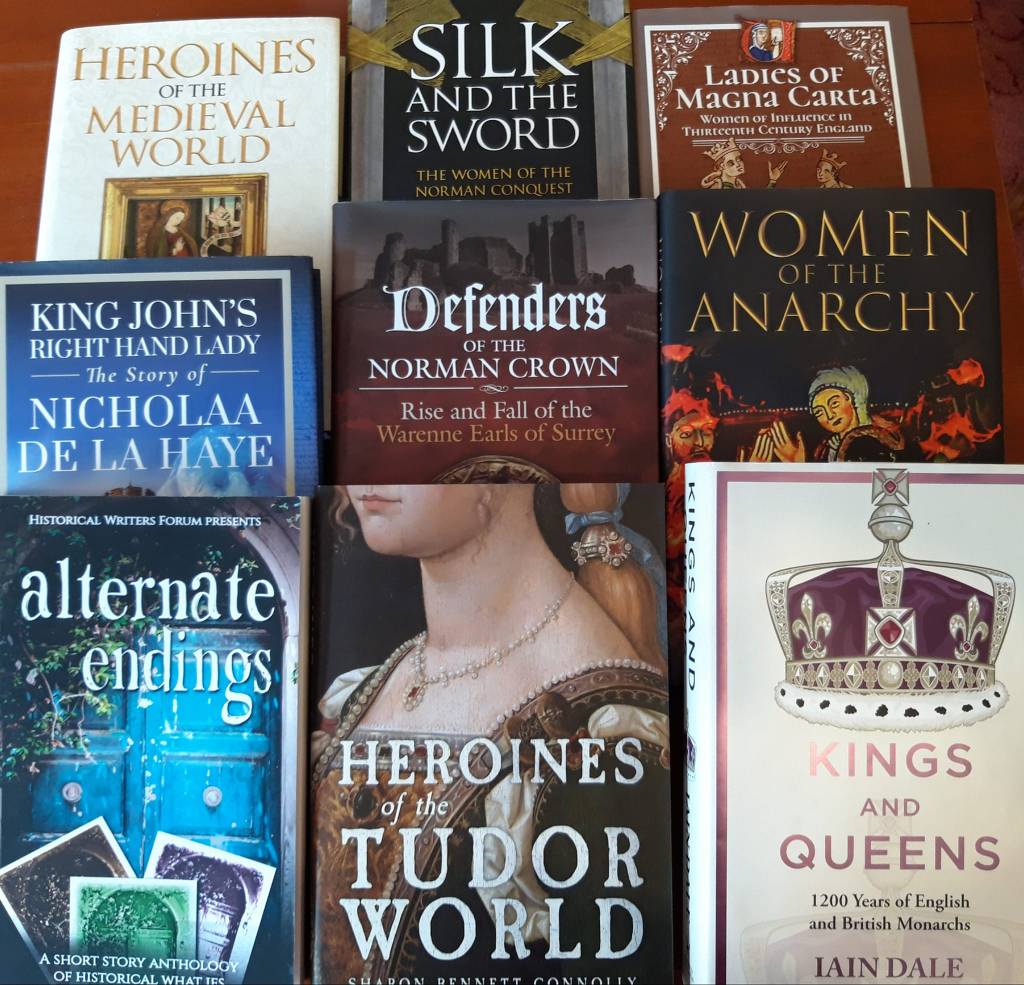

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. It is is available from King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops or direct from Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon. Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org.

Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell and Elizabeth Chadwick, and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

©2015 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS