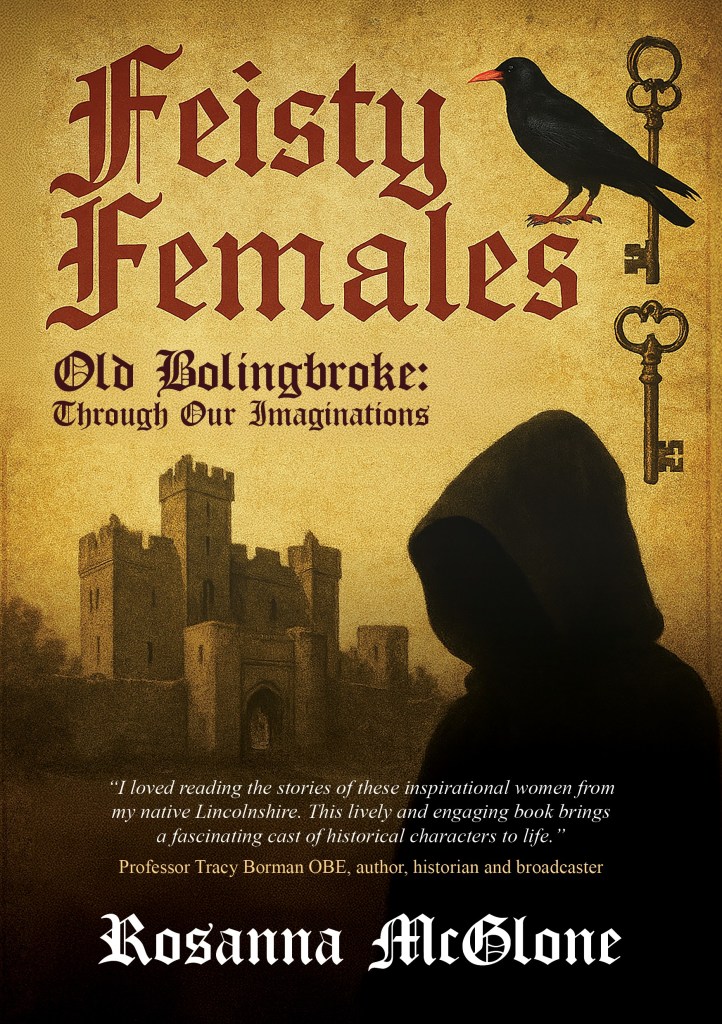

It is a pleasure to welcome my good friend Rosanna McGlone to History … the Interesting Bits to chat about her new book, Feisty Females, a series of short stories inspired by The Great Cowcher Book. Although Feisty Females is Rosanna’s ‘baby’, I feel like its Godmother as we have chatted frequently, over coffee, about the women she included, included Nicholaa de la Haye, Alice de Lacey, Blanche of Lancaster and Gwenllian of Wales – women my readers, I know, are well acquainted with!

Rosanna would meet me, armed with questions about the history of these women and the world they lived in. Then she went away and came back having put her own mark on their stories. And what a fascinating collection of stories it is!

It is a joy to see this project come to fruition. So, over to Rosanna to tell you a little about the process of researching and writing Feisty Females: Old Bolingbroke through our Imaginations.

Feisty Females: Writing Lincolnshire’s Medieval Women by Rosanna McGlone

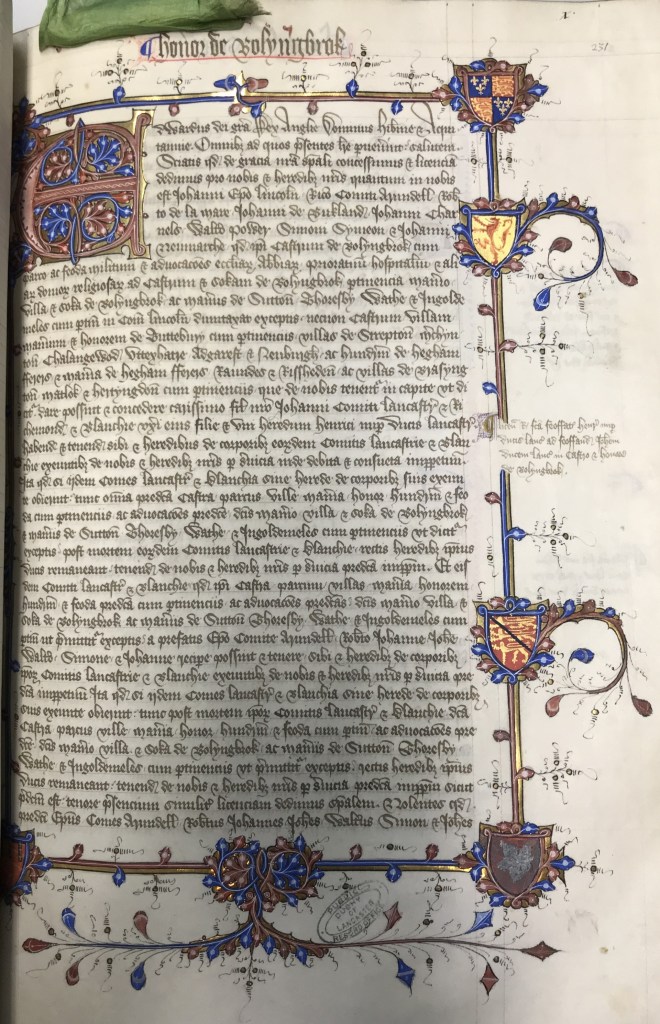

You’ve heard of the Domesday Book, right? But do you know the second most important medieval record book? If you don’t, let me reassure you. Until I received this commission, neither did I. According to staff at the National Archives it’s The Great Cowcher Book, a medieval land registry commissioned by Henry IV to provide a record of lands within the Duchy of Lancaster. Receiver General John Leventhorpe was assigned to visit the 18,000 hectares of rural estates in England and Wales including Cheshire and Lancashire in the West and The Honor of Bolingbroke in Lincolnshire in the East which make up the Duchy of Lancaster. In doing so, he gathered a total of 161 folios and 2,433 charters written in either Latin or medieval French.

What exactly do the two volumes of The Great Cowcher Book contain? As well as including transactions such as the bestowing of Old Bolingbroke Castle to John of Gaunt and his wife Blanche of Lancaster, the book also covers more minor land transactions between people of much lower status.

Additionally, the Great Cowcher Book provides a record of disputes which had been brought before the court seeking resolution.

I was commissioned, and funded, by a number of organisations including the Arts Council, Lincoln County Council, the community of Old Bolingbroke and others to write a creative response to this unique material. Thus, it is from this medieval register that my book of short stories, Feisty Females: Old Bolingbroke through our Imaginations was crafted.

The beautiful medieval manuscripts have recently been translated into English and I received the information on a rather less romanticised, Excel spreadsheet! The columns display the following headings, however not all of them have been populated for each of the more than 5,000 entries: regnal year, name of vendor, name of buyer, land to be purchased; witnesses to the contract; any special conditions, the original language of the manuscript.

As I poured over in excess of 1,200 entries pertaining to The Honor of Bolingbroke, my key focus, I was struck by the names: Walter son of Andrew; Adam, Hugh, Odo Galle of Saltfletby; Gilbert, Ranulf, Clement Prior of Spaldying, William de Rusmar, Henry de Lascy, Simon le Bret, God and his church.

Where were all of the women? As I note in the introduction to my book, His-tory is so often that, a record of the past through the male lens. For me, it was important to offer a different perspective. Out of the more than 5,000 entries within the Great Cowcher Book there are few female landowners. Yet, I was mindful that any females who did appear would have something remarkable about them to succeed in the male dominated medieval world.

Women such as Nicholaa de la Haye, the first female Sheriff of Lincoln and Castellan of Lincoln Castle who withstood not one, but three separate sieges on the castle and earned the respect of King John himself.

Another feisty female for whom I have particular affection is Alice de Lacy, a woman whose story is too incredible to be true, at least that’s what I thought when I read it. Kidnappings, rape, imprisonment by the king, threats of being burnt to death, really how could I possibly capture all of Alice’s turbulent life in a mere 3,000 words? The answer is, I couldn’t. Therefore, I focused upon the catalyst for her troubles, her inheritance. Two bizarre childhood accidents occurred to her brothers which, in my opinion, determined the course of Alice’s life. Firstly, her young brother Edmund fell down a well at Denbigh Castle and died. Then, barely six months later, her other brother, John fell off the battlements at Pontefract Castle. He too perished leaving Alice- still a child herself- as sole heir to her parents, Henry de Lacy, Earl of Lincoln, and Margaret Longespee, Countess of Salisbury.

Whilst all of the other stories are set in medieval times, for Alice’s story I use the framework of a police interview in which she is pushed to reveal the truth of those inciting incidents.

The women with the most charters in the Great Cowcher Book is Hawise de Quincy, first Countess of Lincoln, who has a remarkable 40 entries. Whilst the vast majority of these relate to land acquisitions, the one upon which my tale focuses concerns a dispute was between Hawise and Philip de Kyma. To quote the Great Cowcher, this disagreement was

‘…concerning a certain obstruction of a certain watercourse made by the said Philip in Torp to the nuisance of the port of the said Hawise in Weynfled. Because it was then clear the land of both sides of that watercourse towards the port of Weynfled is of the said Philip…’

And so on… In essence, Philip de Kyma was preventing Hawise de Quincy from accessing her port and, therefore, the valuable port fees. So, what was she to do? This is what my story explores. Does pragmatism work, or must Hawise resort to womanly wiles?

An incredibly wronged female in Feisty Females is Gwenllian, the last Princess of Wales who was incarcerated in a Lincolnshire Priory from which there was little chance of escape, unless she had inside help…

In all cases, bar one, the women come from the Great Cowcher book, however in Matilda’s case my desire to write on the specific topic of that story arose first, based on a certain building referenced in The Great Cowcher. Matilda’s Story begins thus:

It was the day after Candlemas that we held my brother’s funeral. There was just one problem: he wasn’t dead.

It has been a pleasure to learn more about these characters and to bring them to life for readers, giving them voices after 800 years, or more, of silence. The book is a celebration of the female power which was understood by Chaucer who, himself, makes an appearance in Blanche’s Story. In the epigraph to my book Chaucer describes women thus:

‘And what is better than wisedoom? Womman.

And what is better than a good woman? Nothyng.’1

*

Notes: 1. Geoffrey Chaucer, ‘The Tale of Melibee’ The Canterbury Tales.

Images: The Great Cowcher Book (DL 42/2, fol. 231r, the property of His Majesty The King in Right of His Duchy of Lancaster and is reproduced by permission of the Chancellor and Council of the Duchy of Lancaster.); Photos of Henry IV, Nicholaa de la Haye and Gwenllian of Wales are ©Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS.

To Buy the Book:

Just click on the link to buy: Feisty Females

About the Author:

Rosanna McGlone is a writer and journalist. Her book, The Process of Poetry -which explores the development of early drafts of poems by some of the country’s leading poets- was number 1 on Amazon and featured on Radio 4’s Front Row. The sequel, The Making of a Poem, focuses on the work of Australian foremost poets. She has written more than 100 features for the national press, including: The Guardian, The Independent, The Sydney Morning Herald and The Australian. Rosanna has written memoirs, community plays and collected oral histories. Feisty Females, a creative response to The Great Cowcher Book, a medieval book, is out on June 8th 2025.

To find out more follow Rosanna at @rosannamcglone.bsky.social

*

My Books:

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

Out Now! Scotland’s Medieval Queens

Scotland’s history is dramatic, violent and bloody. Being England’s northern neighbour has never been easy. Scotland’s queens have had to deal with war, murder, imprisonment, political rivalries and open betrayal. They have loved and lost, raised kings and queens, ruled and died for Scotland. From St Margaret, who became one of the patron saints of Scotland, to Elizabeth de Burgh and the dramatic story of the Scottish Wars of Independence, to the love story and tragedy of Joan Beaufort, to Margaret of Denmark and the dawn of the Renaissance, Scotland’s Medieval Queens have seen it all. This is the story of Scotland through their eyes.

‘Scotland’s Medieval Queens gives a thorough grounding in the history of the women who ruled Scotland at the side of its kings, often in the shadows, but just as interesting in their lives beyond the spotlight. It’s not a subject that has been widely covered, and Sharon is a pioneer in bringing that information into accessible history.’ Elizabeth Chadwick (New York Times bestselling author)

Available now from Amazon and Pen and Sword Books

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. Heroines of the Tudor World is now available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how Empress Matilda and Matilda of Boulogne, unable to wield a sword themselves, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It shows how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other. Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org. Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell and Michael Jecks, and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

Every episode is also now available on YouTube.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online store.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter, Threads, Bluesky and Instagram.

*

©2025 Sharon Bennett Connolly, FRHistS and Rosanna McGlone