The future king, Harold II Godwinson, was born into an Anglo-Danish family whose extensive influence and power meant they were frequently seen as the power behind the throne. This also meant that they were often seen as a threat to the man wearing the crown – especially Edward the Confessor – and suffered exile as a result.

Harold was born around 1022/3 to Godwin and his wife, Gytha Thorkelsdottir. Gytha was a member of the extended Danish royal family, as her brother, Ulf, was married to King Cnut the Great’s sister, Estrith. Gytha’s nephew, Sweyn Estrithson, would eventually rule Denmark as king. Harold received the earldom of East Anglia in 1044 and, as the oldest surviving son of Godwin, Earl of Wessex, he succeeded to his father’s earldom in 1053. Godwin died at Winchester in Easter week of 1053, after collapsing during a feast to entertain his son-in-law, King Edward the Confessor.

Harold’s sister, Edith, was the wife of King Edward; she had married him in January 1046. However, the fact they had no children meant there was no clear successor to the English crown; a situation that would be a major cause of the crisis of 1066. Of Harold’s brothers three were to become earls; Tostig, Gyrth and Leofwine. However, Tostig was driven out of his earldom of Northumberland by an uprising in 1065 and replaced with Morcar, the brother of Edwin, earl of Mercia. Gyrth and Leofwine both fought – and died – alongside Harold at Hastings. Harold’s older brother, Sweyn, once Earl of Hereford, had left on pilgrimage to Jerusalem in 1051, to atone for his many sins, which included the murder of his own cousin and the kidnapping and rape of an abbess, Eadgifu. He died – or was killed – on his journey home. Another, younger brother, Wulfnoth, was a hostage at the court of William, Duke of Normandy, along with his nephew – Sweyn’s son – Hakon.

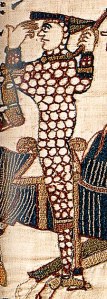

Harold, himself, was not only one of the king’s foremost earls but also one of his most respected advisors and generals. In short, the Godwinsons were the most powerful family in the kingdom, after the king himself – and often resented for the fact. At one point Harold, with his father and brothers, had been exiled from England after quarrelling with the king. During a visit to Normandy in 1064, Harold is even said to have sworn an oath to back William of Normandy’s claim to the English throne in the likely event that Edward the Confessor died without an heir; a claim that William used to the full in order to secure papal approval for his invasion of England.

However, when it came to the moment of truth, it was Harold the old king is said to have named on his deathbed as his successor. He was crowned on 6 January, just hours after the burial of Edward the Confessor in Westminster Abbey. There was no gentle introduction to kingship for King Harold II, however, and almost immediately he had to prepare to defend England against the rival claimants of Norway and Normandy; and against his own brother, Tostig, who had joined forces with Harald Hardrada, King of Norway.

Harold’s love life was as tangled as his political life.

Harold probably met Edith the Swan-neck (or Swanneshals) at about the same time as he became Earl of East Anglia, in 1044, which makes it possible that Edith the Swan-neck and the East Anglian magnate, Eadgifu the Fair, are one and the same. Eadgifu the Fair held over 270 hides of land and was one of the richest magnates in England. The majority of her estates lay in Cambridgeshire, but she also held land in Buckinghamshire, Hertfordshire, Essex and Suffolk; in the Domesday Book, Eadgifu held the manor at Harkstead in Suffolk, which was attached to Harold’s manor of Brightlingsea in Essex, and some of her Suffolk lands were tributary to Harold’s manor of East Bergholt.

While it is by no means certain that Eadgifu is Edith the Swan-neck, several historians – including Ann Williams in the Oxford Database of National Biography – make convincing arguments that they were. Even their names, Eadgifu and Eadgyth, are so similar that the difference could be merely a matter of spelling or mistranslation; indeed, the Abbey of St Benet of Hulme, Norfolk, remembers an Eadgifu Swanneshals among its patrons.

What we do know is that by 1065 Harold had been living with the wonderfully-named Eadgyth Swanneshals (Edith the Swan-neck) for twenty years. History books label her as Harold’s concubine, but Edith was, obviously, no weak and powerless peasant, so it’s highly likely they went through a hand-fasting ceremony – or ‘Danish marriage’ – a marriage, but not one recognised by the Church. It was not an uncommon practice – King Cnut had married his first wife, Ælfgifu of Northampton, in the same fashion. Edith being a hand-fast wife meant that Harold was still free to marry a second ‘wife’ in a Christian ceremony at a later date. Although we can’t say why Harold didn’t marry Edith in a manner recognised by the Church, it may be that they were both young and one or both of their families would not consent to their marriage.

Harold and Edith had about six children together – including three sons, Godwin, Edmund, Magnus and possibly a fourth, Ulf. They also had two daughters. Gytha married Vladimir Monomakh, Great Prince of Kiev, and is the ancestress of the current queen, Elizabeth II, through her descent from Philippa of Hainault. A second daughter, Gunnhild, spent sometime in Wilton Abbey in Wiltshire, although it is not certain that she was there with the intention of becoming a nun, or for safety and protection from the invading Normans. However, she is said to have eloped, before taking her vows, with a Breton knight, Alan the Red.

However, despite their twenty years and many children, and with the health of the king, Edward the Confessor, deteriorating, it became politically expedient for Harold to marry, to strengthen his position as England’s premier earl and, possibly, next king. Ealdgyth of Mercia was the daughter of Alfgar, Earl of Mercia, and granddaughter of the famous Lady Godiva and, according to William of Jumièges, very beautiful. Her brothers were Edwin, Earl of Mercia, and Morcar, who replaced Harold’s brother Tostig as Earl of Northumberland in the last months of 1065.

Ealdgyth was the widow of Gruffuddd ap Llywelyn, King of Gwynedd from 1039 and ruler of all Wales after 1055, with whom she had had at least one child, a daughter, Nest. Gruffuddd had been murdered in 1063, following an English expedition into Wales. Gruffudd’s own men are said to have betrayed their king, killed him and presented his head to Harold in submission. Harold’s subsequent marriage to Ealdgyth, which probably took place at the end of 1065 or beginning of 1066, not only secured the support of the earls of Northumbria and Mercia, but also weakened the political ties of the same earls with the new rulers of north Wales.

As Harold’s wife Ealdgyth was, therefore, for a short time, Queen of England. However, with Harold having to defend his realm, first against Harold Hardrada and his own brother, Tostig, at Stamford Bridge in September of 1066 and, subsequently, against William of Normandy at Hastings, it is unlikely Ealdgyth had time to enjoy her exalted status. At the time of the Battle of Hastings, on 14 October 1066, Ealdgyth was in London, but her brothers took her north to Chester soon after. Although sources are contradictory, it seems possible Ealdgyth was heavily pregnant and gave birth to a son, or twin sons, Harold and Ulf Haroldson, within months of the battle. The identity of Ulf’s mother seems to be sorely disputed, with some believing he was the twin brother of Harold and others that he was the youngest son of Edith Swan-neck; I suppose we will never know for certain.

Unfortunately, we hear nothing of Ealdgyth after the birth of Harold (and Ulf); her fate remains unknown. Young Harold is said to have grown up in exile on the Continent and died in 1098.

Despite his marriage to Ealdgyth of Mercia it seems Edith the Swan-neck remained close to Harold and it was she who was said to be waiting close by when the king faced William of Normandy at Senlac Hill near Hastings on 14 October 1066. She awaited the outcome alongside Harold’s mother, Gytha. Having lost a son, Tostig, just two weeks before, fighting against his brother and with the Norwegians at the Battle of Stamford Bridge, Gytha lost three more sons – Harold, Gyrth and Leofwine and, possibly, her grandson, Haakon, in the fierce battle at Hastings.

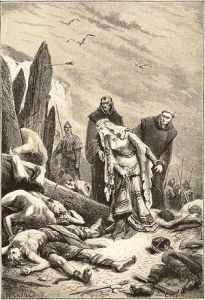

It is heart-wrenching, even now, to think of Edith and the elderly Gytha, wandering the blood-soaked field after the battle, in search of the fallen king. Sources say that Gytha was unable to identify her sons amid the mangled and mutilated bodies. It fell to Edith to find Harold, by undoing the chain mail of the victims, in order to recognise certain identifying marks on the king’s body – probably tattoos. There is a tradition, from the monks of Waltham Abbey, of Edith bringing Harold’s body to them for burial, soon after the battle. Although other sources suggest Harold was buried close to the battlefield, and without ceremony, it is hard not to hope that Edith was able to perform this last service for the king. However, any trace of Harold’s remains was swept away by Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries, so the grave of England’s last Anglo-Saxon king is lost to history.

After another year or so of leading resistance to Norman rule in the south-west, Harold’s mother, Gytha, eventually fled into exile on the Continent, taking Harold and Edith’s daughter, another Gytha, with her. Gytha and her nephew, Swein Estrithson, King of Denmark, arranged the marriage of the younger Gytha to the prince of Smolensk and – later – Kiev, Vladimir II Monomakh.

Edith and Harold’s sons fled to Ireland with all but one living into the 1080s, though the dates of their eventual deaths remain uncertain. Gunnhild remained in her nunnery at Wilton until sometime before 1093, when she became the wife or concubine of Alan the Red, a Norman magnate. Whether or not she was kidnapped seems to be in question but when Alan died in 1093, instead of returning to the convent, Gunnhild became the mistress of Alan’s brother and heir, Alan Niger. Alan Rufus held vast lands in East Anglia – lands that had once belonged to Eadgifu the Fair and, if Eadgifu was Edith the Swan-neck, it’s possible that Alan married Gunnhild to strengthen his claims to her mother’s lands.

After 1066 Edith’s lands had passed to Ralph de Gael, but he rebelled against King William and so they were eventually given to Alan the Red. Gunnhild and Alan are thought to have had a daughter, Matilda, who was married to Walter d’Eyncourt. Matilda and Walter’s oldest son, William d’Eyncourt, died as a child whilst fostered in the household of William II Rufus. He was buried in Lincoln Cathedral; his grave is now lost but his grave marker is preserved in the cathedral’s museum.

Of Edith the Swan-neck, there is no trace after Harold is interred at Waltham Abbey. Although she spent twenty years at the side of the man who would become king, and her daughter, Gytha, would be an ancestress of the English royal family of today, Edith simply disappears from the pages of history. Overall, history has treated Edith kindly; sympathising with a woman who remained loyal to her man to the end, despite the fact her official status was questionable.

*

Pictures ©2018 Sharon Bennett Connolly except Lady Godiva, which is courtesy of the Rijksmuseum and Edith at Hastings and William the Conqueror, which are courtesy of Wikipedia.

*

Sources: The English and the Norman Conquest by Dr Ann Williams; Brewer’s British Royalty by David Williamson; Britain’s Royal Families, the Complete Genealogy by Alison Weir; The Wordsworth Dictionary of British History by JP Kenyon; The Norman Conquest by Marc Morris; Harold, the King Who Fell at Hastings by Peter Rex; The Anglo-Saxons in 100 Facts by Martin Wall; The Anglo-Saxon Age by Martin Wall; Kings, Queens, Bones and Bastards by David Hilliam; The Mammoth Book of British kings & Queens by Mike Ashley; The Oxford Companion to British History Edited by John Cannon; The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles translated and edited by Michael Swaton; The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle translated by James Ingram; Queen Emma and the Vikings by Harriett O’Brien; The Bayeux Tapestry by Carola Hicks; oxforddnb.com.

*

My books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online store.

Out now: Scotland’s Medieval Queens

Scotland’s history is dramatic, violent and bloody. Being England’s northern neighbour has never been easy. Scotland’s queens have had to deal with war, murder, imprisonment, political rivalries and open betrayal. They have loved and lost, raised kings and queens, ruled and died for Scotland. From St Margaret, who became one of the patron saints of Scotland, to Elizabeth de Burgh and the dramatic story of the Scottish Wars of Independence, to the love story and tragedy of Joan Beaufort, to Margaret of Denmark and the dawn of the Renaissance, Scotland’s Medieval Queens have seen it all. This is the story of Scotland through their eyes.

‘Scotland’s Medieval Queens gives a thorough grounding in the history of the women who ruled Scotland at the side of its kings, often in the shadows, but just as interesting in their lives beyond the spotlight. It’s not a subject that has been widely covered, and Sharon is a pioneer in bringing that information into accessible history.’ Elizabeth Chadwick (New York Times bestselling author)

Available now from Amazon and Pen and Sword Books

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. Heroines of the Tudor World is now available from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how Empress Matilda and Matilda of Boulogne, unable to wield a sword themselves, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It shows how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other. Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org. Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell, Scott Mariana and Michael Jecks, and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

Every episode is also now available on YouTube.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online store.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter, Threads, Bluesky and Instagram.

*

©2018 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS