If you have visited the British Library’s latest exhibition, Medieval Women: In Their Own Words, you may have spotted the work of Marie de France. Marie was a poet in the late 12th century, who wrote three major works that can be definitively attributed to her, even though we don’t know who she was. All that is left of Marie is her work, and the vague notion that she comes from France, because she wrote in her Fables ‘Marie ai num, si sui de France’.1 The traditional view is that Marie was a Frenchwoman writing at the court of Henry II of England based on the fact that if she was writing in France, she wouldn’t have to say that she was from that country. However, France in the 12th century was far from one unified, indivisible country. In fact, it was a series of counties and duchies with their own rulers, who paid homage to the King of France; the French king’s own domains at the time were the Île-de- France, which incorporated Paris and its environs.

Another argument for Marie writing in England, is that her lais, her poetic verses, were dedicated to a ‘noble reis’, or ‘noble king’, and this is thought to be Henry II of England. However, it could just as easily been intended for Louis VII of France, or his son Philip II Augustus. In turn the Fables, an adaptation of Aesop’s Fables, were dedicated to a nobleman she identifies as ‘Count William’. There were several earls in England at the time who were named William, including William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke; William Longspée, Earl of Salisbury; and William Mandeville, Earl of Essex; or even the son of King Stephen, William of Blois, Earl of Warenne and Surrey. However, William was a common name at the time, even on the Continent, where you could find many a Guillaume.

Everything we think we know about who Marie was is pure conjecture. It has even been suggested that she was the illegitimate daughter of Geoffrey of Anjou, father of Henry II, and therefore a half-sister of Henry. She has also been variously identified as a nun at Reading Abbey, the abbess of Shaftesbury between 1181 and 1216, and Marie de Meulan, wife of Hugh Talbot of Cleuville.2 We do know that Marie had a knowledge of Latin and English, and a familiarity with the works of Ovid and Wace’s Brut, and wrote in an Anglo-Norman French.

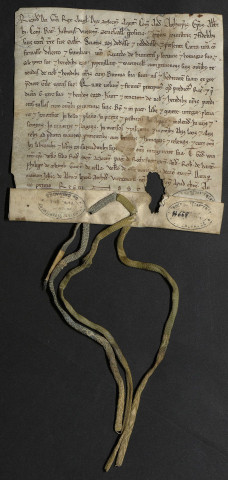

Her works have been dated to the second half of the 12th century, with her poetry, the lais, dating between 1160 and 1199, the Fables between 1160 and 1190, and her last work, the Espurgatoire, has been dated to after 1189 and possibly as late as 1215.3 L’Espurgatoire Seint Patriz (The Purgatory of St Patrick) is believed to have been written after 1189 as it appears to have been heavily reliant on the Latin text of Henry of Saltrey as her source, which was published around 1185. L’Espurgatoire is dedicated to ‘H. abbot of Sartis’, who may have been Hugh, Abbot of Wardon Abbey, in Bedfordshire, between 1173 and 1185 or 1186; the abbey was originally named St Mary de Sartis.4 The only surviving manuscript of this treatise is now stored in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris.

The lais were a series of twelve poems, many of which were drawn from Celtic legends. Only one is based on Arthurian legends, specifically the story of the lovers, Tristan and Iseult. Many of the lais were translated into Old Norse in the 13th century, while two, Lanval and Le Fresne were translated and adapted into Middle English in the 14th century. The lais were narratives, written in verse and intended to be set to music. One such included the lines; ‘when a good thing is well known, it flowers for the first time, and when it is praised by many, its flowers have blossomed.’5

Marie’s stories included fairy mistresses, twins separated at birth, and one relating the troubles of the wife of a werewolf. Her lais explored love and conflicting loyalties; they dealt with the issues of courtly behaviour and documented the struggles to fulfil the conflicting aims of individual needs and cultural expectations. They varied in length, with the shortest, Chevrefoil, having 118 lines and the longest, Eliduc, comprising 1,184 lines; this last was the story of a wife having to adapt when her husband brings home a second wife.

Marie’s collection of Fables, known as Ysopets in French and written for the mysterious ‘Count William’, are based on the older Aesop’s Fables, from antiquity, but she also adapted and added to the original stories. The Fables, a rhyming collection of works, demonstrate Marie’s concern for the well-being of the lower classes and the poor, criticising the political and social conditions of the time. Her work was widely read and influential; the fable Del cok e del gupil (The Cock and the Fox) is one of the inspirations for Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Nun’s Priest’s Tale, written in the 15th century. Marie ends The Fables with an epilogue, in which she includes a plea to be remembered,

To end these tales I’ve here narrated

And into Romance tongue translate,

I’ll give my name for memory:

I am from France, my name’s Marie.

And it may hap that many a clerk

Will claim as his what is my work.

But such pronouncements I want not!

It’s folly to become forgot!6

Wherever she came from, geographically and socially, Marie de France was a keen observer of the social undercurrents of the time, incorporating them into her Lais and Fables. And we cannot say for certain that her work was produced in England, at the English court. With the Anglo-Norman empire stretching from the borders of Scotland to the borders of Spain she may have travelled within Henry II’s domains, but not necessarily with the court. Although we have few clues to her identity and origins, at least we have her works – her poetry through which she has lived on for more than eight centuries.

Notes:

1. ‘My name is Marie and I am from France’, quoted in Rethinking Marie by Dinah Hazell; 2. Marie (fl. c.1180–c.1189) (article) by Tony Hunt; 3. Rethinking Marie by Dinah Hazell 4. Marie (fl. c.1180–c.1189) (article) by Tony Hunt; 5. The Plantagenet Chronicles edited by Elizabeth Hallam; 6. Translated from; ‘Al finement de cest escrit, Que en romanz ai treité e dit, Me numerai pur remembrance: Marie ai num, si sui de France. Put cel ester que clerc plusur Prendreient sur eus mun labur. No voil que nul sur li le die! E il fet que fol ki sei ublie!’ Taken from Marie de France: Fables, edited and translated by Harriet Spiegel.

Images: Courtesy of Wikipedia

Sources:

Marie de France: Fables, edited and translated by Harriet Spiegel; Dinah Hazell, Rethinking Marie, (article) sfsu.edu; Tony Hunt, Marie (fl. c.1180–c.1189) (article), ODNB; Elizabeth Hallam, editor, The Plantagenet Chronicles; The Plantagenets, the Kings who Made England by Dan Jones; History Today Companion to British History Edited by Juliet Gardiner and Neil Wenborn; he Plantagenets, the Kings that made Britain by Derek Wilson; England Under the Norman and Angevin Kings by Robert Bartlett; Roy Strong The Story of Britain.

*

My Books:

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

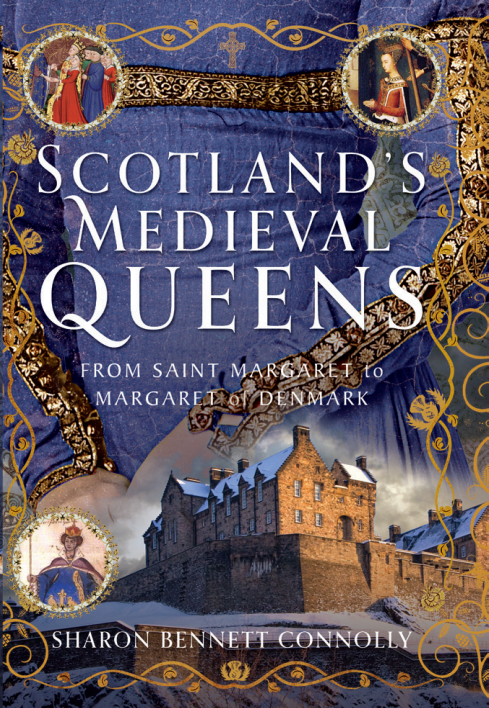

Coming 30 January 2025: Scotland’s Medieval Queens

Scotland’s history is dramatic, violent and bloody. Being England’s northern neighbour has never been easy. Scotland’s queens have had to deal with war, murder, imprisonment, political rivalries and open betrayal. They have loved and lost, raised kings and queens, ruled and died for Scotland. From St Margaret, who became one of the patron saints of Scotland, to Elizabeth de Burgh and the dramatic story of the Scottish Wars of Independence, to the love story and tragedy of Joan Beaufort, to Margaret of Denmark and the dawn of the Renaissance, Scotland’s Medieval Queens have seen it all. This is the story of Scotland through their eyes.

Available for pre-order now.

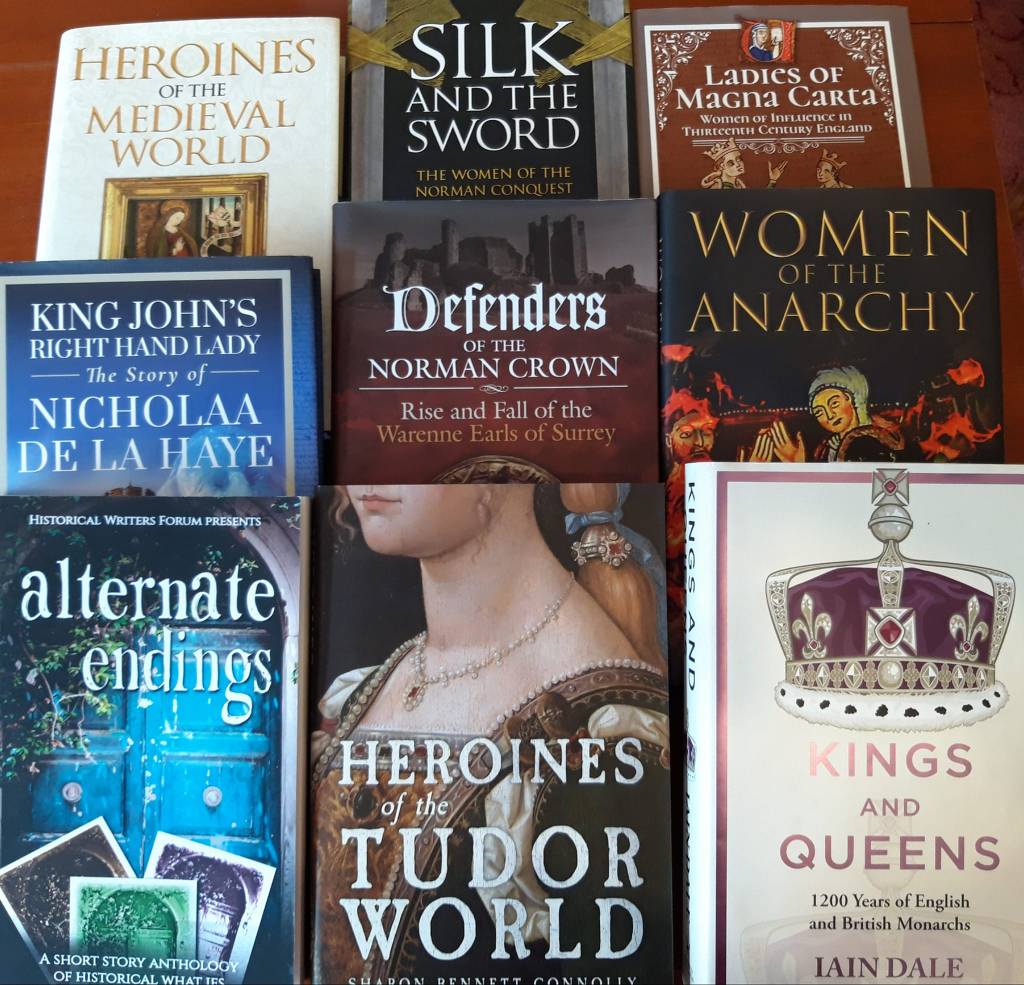

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. Heroines of the Tudor World is now available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how Empress Matilda and Matilda of Boulogne, unable to wield a sword themselves, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It shows how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other. Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

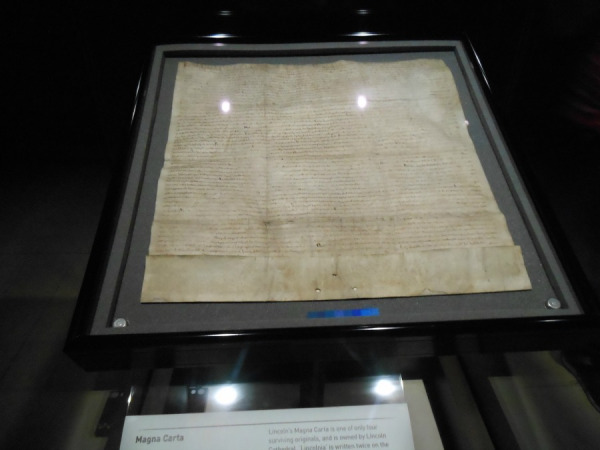

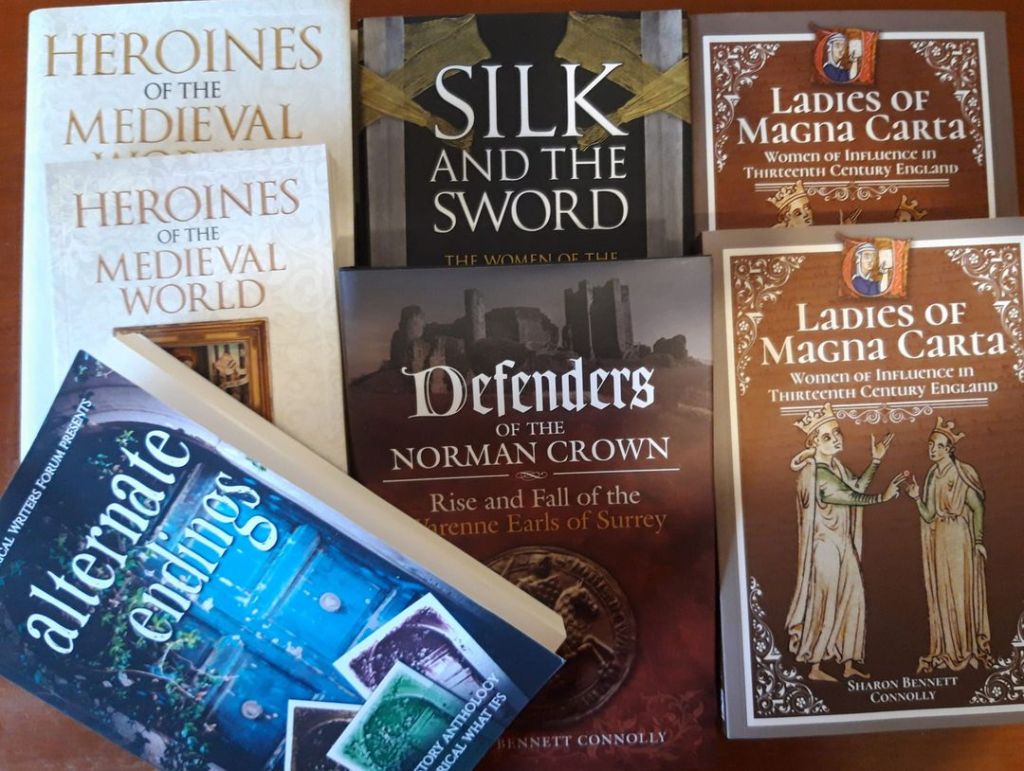

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org. Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell, and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter, Threads, Bluesky and Instagram.

©2024 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS