The time commonly referred to as the Anarchy is one of the most violent and unstable periods of English history. Lasting almost the entirety of the reign of King Stephen, it truly was a Cousin’s War. The two main protagonists, King Stephen and Empress Matilda, were first cousins, both being grandchildren of William the Conqueror and his queen, Matilda of Flanders. What is perhaps less well known is that Empress Matilda was also first cousin to Stephen’s wife and queen, Matilda of Boulogne. The two Matilda’s were both granddaughters of Margaret of Wessex, Queen of Scots as the wife of Malcolm III Canmore. And later St Margaret. It is through Margaret that the namesake cousins could claim descent from Alfred the Great.

The origins to the Anarchy can be traced back to one dramatic and tragic event: the sinking of the White Ship in 1120. This saw the drowning of the only legitimate son and heir of King Henry I, William Ætheling (or Adelin). The young man was 17 years old at the time, recently married, and his father’s pride and joy. His death gave rise to a constitutional crisis which the widowed Henry I sought to resolve by his speedy marriage to the teenage Adeliza of Louvain, in the hope of begetting yet more sons. Although he was getting on in years at roughly fifty-two, and had only two legitimate children, his brood of more than twenty illegitimate, but acknowledged, offspring gave him cause for optimism.

However, as the years progressed and no children were born, Henry had to look to other ways of resolving the succession crisis. In the years since the death of his son, the king had taken his nephew Stephen of Blois under his wing, showering him with gifts and land, and arranging the young man’s marriage. Stephen was the son of Henry’s highly capable sister Adela of Normandy, Countess of Blois and Stephen, Count of Blois, who had been killed on Crusade. The younger Stephen was created Count of Mortain and married to Matilda of Boulogne, the only child and heiress of Eustace of Boulogne and Mary of Scotland. It is possible that Henry was showing Stephen such favouritism in anticipation of not producing an heir by his new wife and was grooming Stephen to succeed him.

However, the death of his daughter’s husband, Emperor Henry V, in faraway Germany offered Henry an alternative to his nephew. Better still, here was an opportunity to put his own blood on the throne. Shortly after the German emperor’s death in 1125, Henry recalled Empress Matilda to England. She had been sent to Germany at the age of seven, to be raised at the court of the emperor in anticipation of their marriage when she came of age. Matilda had married Henry in 1114, a month before her twelfth birthday. Although she and Henry were married for eleven years, they remained childless. When Henry died in 1125, Henry I of England therefore saw an opportunity to resolve his succession problem by recalling Matilda and making her his heir.

There was one problem with this plan: Matilda was a woman. Henry knew his barons would not be happy with the idea of being ruled by a woman, but by a process of coercion and persuasion he managed to get all his barons to swear to accept her as their next monarch. Following Matilda’s arrival in England in 1126, Henry proceeded to extract oaths of allegiance to her from all the bishops and magnates present at his Christmas court. Notably, this included Stephen of Blois, Count of Mortain, King Henry’s nephew and the empress’s cousin. One of the concessions made to the barons was that they would have a say in Matilda’s choice of husband. After all, as a woman, Matilda would need a husband to rule in her name. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reported:

David the king of Scots was there, and all the head [men], clerical and lay, that were in England; and there he [Henry] had archbishops, and bishops, and abbots, and earls, and all those thegns who were there, swear England and Normandy after his day into the hand of his daughter Æthelic [Matilda], who was earlier wife of the emperor of Saxony; and afterwards sent her to Normandy (and with her travelled her brother Robert, Earl of Gloucester, and Brian, son of the earl Alan Fergant), and had her wedded to the son of the Earl of Anjou, [who] was called Geoffrey Martel [Plantagenet]. Despite the fact that it offended all the French and English, the king did it in order to have peace from the Earl of Anjou and in order to have help against William his nephew.1

In trying to resolve the issue of who would rule after him, Henry had inadvertently created a problem that ensured the succession would be anything but smooth. He had created two rivals for the throne. His daughter had the claim that she was Henry’s successor by blood, but she was a woman. Though his blood claim was weaker, Stephen was Henry’s closest living male relative, and in the days when a king not only had to rule but had to lead his men into battle, the prospect of a female ruler struck fear into the hearts of the barons.

Empress Matilda’s actual abilities mattered less than the fact of her gender. Raised at the German imperial court, Matilda was an experienced politician who had acted as regent for her first husband on several occasions. She was confident. She knew, beyond doubt, that she was capable of ruling in her own right. This confidence was her strength but also her weakness; the barons would surely baulk at the idea of a woman who was unwilling to take instruction from them. In contrast, King Stephen was a magnate who was experienced in war and had enjoyed the favour of King Henry I.

Stephen’s wife, Matilda of Boulogne, was a stalwart supporter of her husband. She was arguably more capable than Stephen and often took the initiative in diplomatic negotiations. Acting as Stephen’s queen, she offered a stark contrast to the independence and authority of Empress Matilda that so infuriated the barons. Matilda of Boulogne was a little more subtle than her imperious counterpart, only ever acting in her husband’s name, not her own. Even later, when she held the command of Stephen’s forces during his captivity in 1141, she claimed to act only on behalf of her husband and sons.

Matilda of Boulogne was an example of how a woman was expected to act and comport herself: strong and confident, but subject to her husband’s will. On this last, Empress Matilda failed in the eyes of the barons; she was acting for herself. In the event, the barons of England and Normandy despised her second husband, Geoffrey of Anjou, so they would have been even less receptive to Matilda had her husband tried to assert his authority. It was a conundrum that Matilda was never able to resolve, though she would not give up trying.

And the empress was, ultimately, the winner. With Stephen’s death in 1154, the last flickers of conflict also died. The empress’s oldest son succeeded as Henry II, peacefully and largely unopposed, despite the continued presence of Stephen’s son, William of Blois. Support for William was non-existent, and the war-weary barons were more than happy with the settlement. For Empress Matilda, it must have been a bittersweet moment. She had spent most of the past nineteen years fighting for her birthright and that of her son. While she had never worn the crown, Henry now did. The line of succession had finally passed into the hands of the descendants of Henry I.

Her bloodline had prevailed, but King Stephen had denied Empress Matilda her inheritance, her titles and her due. The irony of this struggle is that, in order to claim the throne, Stephen overruled the same laws of inheritance that saw him become Count of Boulogne. While it was difficult for a woman to manage her own lands and titles, they descended through her to her husband or son. So, as the county of Boulogne was inherited by Queen Matilda, so Stephen held those titles by right of his wife. And this was the dilemma for the Anglo-Norman nobility, and the reason they largely chose to support Stephen: they were suspicious and distrusting of the husband chosen for Empress Matilda. Just like Stephen, Geoffrey of Anjou had every right to claim Matilda’s lands as his own. Not the Geoffrey showed any interest in England; his sights were firmly set on Normandy, which he had conquered by 1144 and handed to his son, Henry in 1150.

The similarities between Empress and Queen are more noticeable than their differences. Both women demonstrated a level of piety which can only have come from their family connection, namely their mutual descent from Margaret of Wessex, Queen of Scots and later saint. Each Matilda was willing to do whatever it took to protect the interests of her children. Queen Matilda appealed to the empress to protect her son Eustace’s inheritance, while the empress invaded England. It is easy to see the empress’s struggle as an expression of her personal ambition to recover the inheritance stolen from her.

Yet it is necessary to look deeper and acknowledge that she was also motivated to see her son achieve his birthright. When Stephen usurped her throne, he stole it not just from Matilda but also from Henry. Calling himself Henry Fitz Empress when he joined his mother’s struggle, Henry was the grandson and eventual heir of Henry I. He had been raised to believe that England and Normandy were his destiny, and with the knowledge that his mother was absent for much of his formative years because she was fighting for his inheritance as much as hers.

Both empress and queen were adept at negotiating to achieve their aims, demonstrating impressive diplomatic skills in the most difficult of circumstances. Neither was prepared to sit on the sidelines and let others fight their battles for them. Although they could not wield a sword, nor participate in warfare, neither did they sit and wait in the safety of their ivory towers. They travelled with the armies and participated in councils of war, advising, directing and commanding their forces.

Empress Matilda and Queen Matilda had so much more in common than a name. Indeed, there was more to uniting them than pitting them against one another, be it family ties, abilities or aspirations for their children. What really differentiated them was the way they went about achieving their aims.

Dynastic ambition was a fine line for a woman to walk…

*

The story of Empress Matilda and Queen Matilda of Boulogne is examined in greater detail in my book, Women of the Anarchy.

Notes:

1. Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, edited by Michael Swanton

Sources:

Gesta Stephani, translated by K. R. Potter; Henry of Huntingdon, The History of the English People 1000-1154; Marjorie Chibnall, The Empress Matilda: Queen Consort, Queen Mother and Lady of the English; Teresa Cole, The Anarchy: The Darkest Days of Medieval England; Catherine Hanley, Matilda: Empress, Queen, Warrior; Helen Castor, She-Wolves: The Women who Ruled England before Elizabeth; Robert Bartlett, England Under the Norman and Angevin Kings; J. Sharpe (trans.), The History of the Kings of England and of his Own Times by William Malmesbury; Orderici Vitalis, Historiae ecclesiasticae libri tredecem, translated by Auguste Le Prévost; Chronicles of the Reigns of Stephen, Henry II and Richard I; Edmund King, King Stephen; Donald Matthew, King Stephen; Matthew Lewis, Stephen and Matilda’s Civil War: Cousins of Anarchy.

Images:

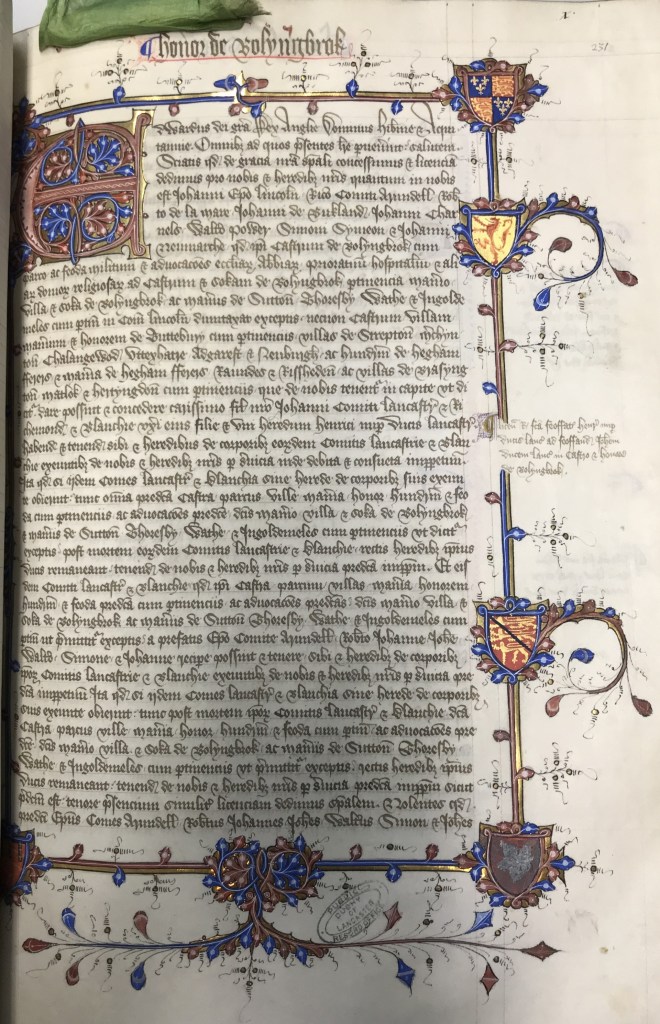

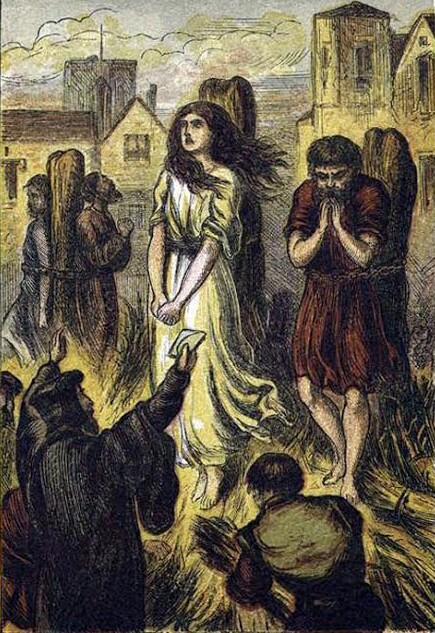

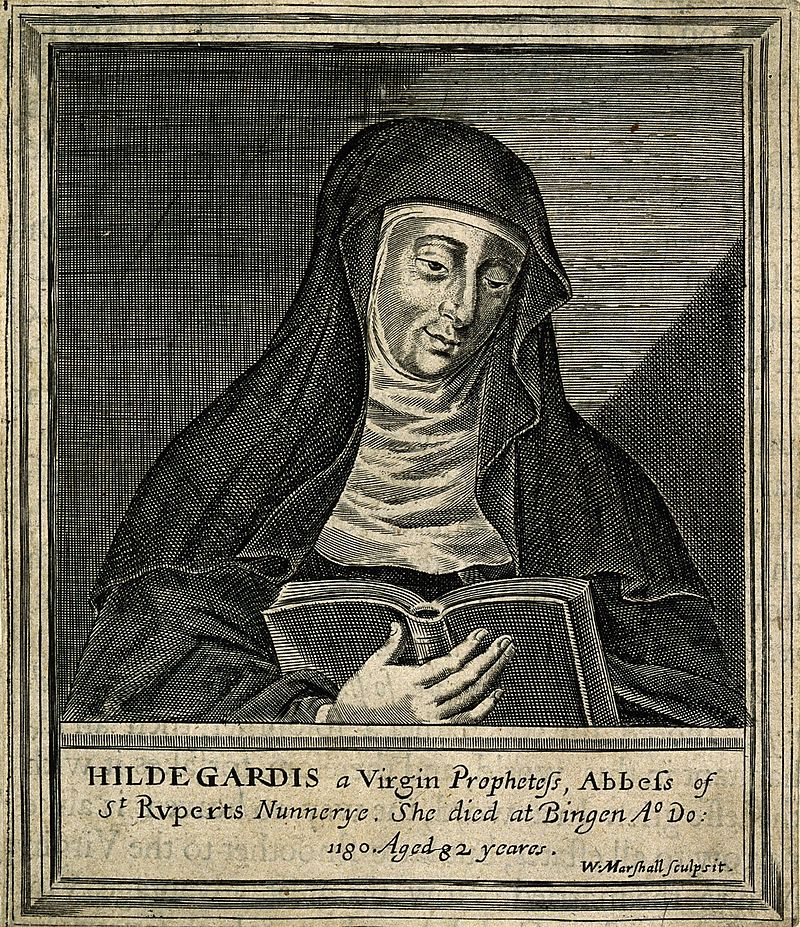

Courtesy of Wikipedia except King Stephen and Henry II which are ©2025 Sharon Bennett Connolly, FRHistS.

*

My Books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

Out now: Scotland’s Medieval Queens

Scotland’s history is dramatic, violent and bloody. Being England’s northern neighbour has never been easy. Scotland’s queens have had to deal with war, murder, imprisonment, political rivalries and open betrayal. They have loved and lost, raised kings and queens, ruled and died for Scotland. From St Margaret, who became one of the patron saints of Scotland, to Elizabeth de Burgh and the dramatic story of the Scottish Wars of Independence, to the love story and tragedy of Joan Beaufort, to Margaret of Denmark and the dawn of the Renaissance, Scotland’s Medieval Queens have seen it all. This is the story of Scotland through their eyes.

‘Scotland’s Medieval Queens gives a thorough grounding in the history of the women who ruled Scotland at the side of its kings, often in the shadows, but just as interesting in their lives beyond the spotlight. It’s not a subject that has been widely covered, and Sharon is a pioneer in bringing that information into accessible history.’ Elizabeth Chadwick (New York Times bestselling author)

Available now from Amazon and Pen and Sword Books

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. Heroines of the Tudor World is now available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how Empress Matilda and Matilda of Boulogne, unable to wield a sword themselves, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It shows how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other. Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org. Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

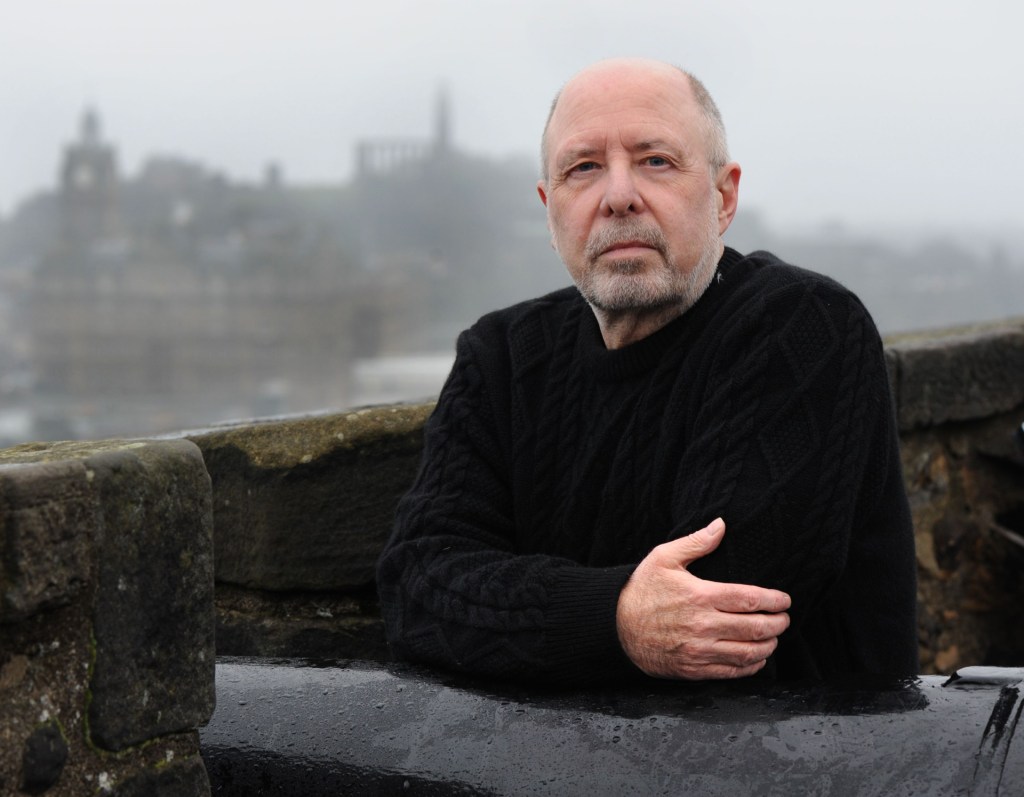

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved. Our first ever episode was a discussion on The Anarchy Every episode is also now available on YouTube.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter, Threads, Bluesky and Instagram.

*

©2025 Sharon Bennett Connolly, FRHistS.