Nicholaa de la Haye first came to the attention of the chroniclers in the year 1191. She and her husband, Gerard de Camville, were in command of Lincoln Castle. Gerard was a talented administrator and was sheriff of Lincoln in 1189 and 1190 and again from 1199 to 1205. He was also hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle by right of his wife, Nicholaa. Although he had sworn allegiance to King Richard on his accession, in 1191 Gerard paid homage to the king’s brother John, then count of Mortain, for Lincoln Castle. This meant that Gerard and Nicholaa would be drawn into John’s dispute with King Richard’s chancellor, William Longchamp.

Before King Richard’s departure on crusade, the king had extracted a promise from John and their illegitimate half-brother Geoffrey, Archbishop of York, that neither would set foot in England for three years. Although it seems highly unlikely that Longchamp released John from his oath, the prince was back in England by 1191, possibly on the insistence of his mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, who was watching over her favourite son’s domains while he was away on crusade.

Longchamp’s heavy-handed administration of the country caused much dissent among the barons and John chose to champion their cause. The catalyst for John’s armed opposition to William Longchamp may well have been the king’s recognition of his nephew, Arthur, Duke of Brittany still only a child of five years, as his heir; the only person in England who was meant to know was William Longchamp. However, it seems that Longchamp may have sounded out others to measure the level of support for Arthur. According to the chronicler William of Newburgh, he passed on the information to the king of Scots, at least, and possibly some of the Welsh princes. In early 1191 the news was widely leaked, and John came to hear of it.

According to William of Newburgh, John had expected to become the successor to the kingdom, should the king not survive the cursade. Indeed, Richard’s advancement of his brother since his accession, in giving John lands in England and arranging his marriage to an English bride, all seemed to support this expectation. Richard’s actions in naming Arthur his heir, and Longchamp’s support for this, threatened to undermine John’s own claims and rights. Having heard the not-so-secret secret, John started building up his own powerbase. According to Richard of Devizes, John, ‘when he knew for certain that his brother had turned his back on England, presently perambulated the kingdom in a more popular manner, nor did he forbid his followers calling him the king’s heir.’

Tensions were rising. Richard of Devizes reported that, as a result of the king’s departure on crusade, the nobles were ‘all stirred up in arms, castles closed, cities fortified and entrenchments thrown up.’

John sent out letters, in secret, eliciting the support of the nobles against the justiciar. The king himself was so concerned over events in England that, in the spring, he had released Walter de Coutances, archbishop of Rouen, from his crusading vow and sent him back to sort things out. The king must have had concerns about the efficacy of William Longchamp’s rule, as he also sent a letter, to William Marshal, Hugh Bardolf, Geoffrey Fitz Peter and William Brewer, in which he ordered ‘If our chancellor does not act faithfully according to the advice of yourselves and others to whom we have committed the care of our kingdom, we order you to carry out your own dispositions in all the affairs of our kingdom, in castles and escheats, without any dispute.’

Walter de Coutances landed at Shoreham on 27 June, 1191. The situation had already escalated, however.

In 1190, on returning from his investigation into the massacre of the Jews of York, Longchamp stopped at Lincoln. He accused Gerard de Camville of harbouring thieves and robbers who preyed on the merchants attending the fair at Stamford. Longchamp had demanded that Gerard de Camville, described as ‘an enemy of the chancellor’ by the Crowland Chronicle, relinquish his custody of Lincoln Castle and swear allegiance to him, personally, as justiciar. Camville refused and instead ‘had done homage to Earl John, the king’s brother, for the castle of Lincoln, the custody whereof is known to belong to the inheritance of Nicholaa, the wife of the same Gerard, but under the king.’1

In acting against Gerard de Camville, Longchamp had forced him into John’s arms. On learning of Gerard’s defiance, Longchamp sent overseas for foreign mercenaries and set out north with the troops he had under his command, attacking Wigmore along the way and forcing Roger de Mortimer, impeached for conspiracy against the king, to surrender his castles and abjure England for three years. As Gerard de Camville joined John at Nottingham, Longchamp continued to Lincoln where he besieged the castle as ‘Gerard was with the earl; and his wife Nicholaa proposing to herself nothing effeminate defended the castle like a man. The chancellor was wholly busied about Lincoln.’2

The formidable Nicholaa refused to yield, holding out for forty days before Longchamp raised the siege, having heard that Tickhill and Nottingham had fallen to John.

Gerard’s decision to leave Nicholaa in command of the castle, even though Longchamp was heading her way with an army, may have been to emphasise the standing of the de la Haye family in Lincolnshire, and its connections to the castle itself. He believed Lincoln would rally to her side. That he did not appoint a male deputy to take charge is testament to his trust in Nicholaa and her abilities. She had, after all, grown up with the castle as her birth right and would have been familiar with every part of its defences, its strengths and weaknesses. Although she would not have been able to fight, with sword and shield, she could direct the defence, placing soldiers where they were most needed, organising supplies of weapons and ammunition, and ensuring the stores of food and drink were suitably rationed.

Nicholaa was approaching forty when William Longchamp besieged her. She was no young, inexperienced girl, and she would have been used to command – and to her orders being obeyed. She was also a mother, of a daughter in her teens and at least two young boys, but it is unlikely that the children were in the castle; it is more likely they were being raised on her manor at Brattleby, just to the north of Lincoln. The castle itself may appear difficult to defend. The curtain wall was a third of a mile in length, but there was a steep drop on the south side. There were two main entrances, the East and West gates, and a number of postern gates. These had to be guarded closely. Similarly, the castle would also have been difficult to attack, and besiegers would have concentrated their energies on the main and postern gates. There is no record of Longchamp bringing up siege machinery, so it would have been a case of watching and waiting and hoping to starve out the castle occupants.

Nicholaa held out for forty days, as demonstrated by the Pipe Roll of 1191, which showed that mercenaries were employed for that length of time on the siege of Lincoln Castle. All the same, it must have been a relief for Nicholaa, when William Longchamp gave up the siege and marched his soldiers away.

According to Roger of Howden, the chancellor besieged Lincoln Castle, ‘having expelled Gerard de Camville from the keepership and the office of sheriff of Lincoln; which former office the chancellor gave to William de Stuteville and made him sheriff as well.’ John, in turn moved north in support of Gerard, quickly taking the ill-prepared royal castles of Tickhill (in Yorkshire) and Nottingham and demanding that Gerard de Camville be reinstated, saying that he ‘would visit him [the chancellor] with a rod of iron’.3

John admonished Longchamp, saying ‘it was not proper to take from the loyal men of the kingdom, well known and free, their charges and commit them to strangers and men unknown; that it was a mark of his folly that he had intrusted the king’s castles to such, because they would expose them to adventurers; that if it should go with every barbarian with that facility, that even the castles should be ready at all times for their reception, that he would no longer bear in silence the destruction of his brother’s kingdom and affairs.’4

In the meantime, Walter de Coutances, Archbishop of Rouen but an Englishman by birth, had landed in England and hastened north to act as intermediary between the two warring factions. At some point in the escalating tensions, as Roger of Howden reports, William Longchamp, as papal legate, also issued a sentence of excommunication on John’s supporters. The list included John’s leading supporters, as well as Walter de Coutances, archbishop of Rouen, and Gerard de Camville.

Despite the blatant mistrust on both sides, settlement was reached, with the aid of bishops trusted by both men, and of barons who ‘swore that they would provide satisfaction between the earl and the chancellor concerning their quarrels and questions to the honour of both parties and the peace of the kingdom.’5 Agreement, mostly favourable to John, was reached whereby John would relinquish the castles he had taken, but then Longchamp would give Tickhill into the custody of Reginald de Wasseville and Nottingham to William de Wenn, both men of John’s affinity who each agreed to give up a hostage to the chancellor. John also promised not to harbour outlaws in his lands. Longchamp also agreed to drop his support for Arthur as Richard’s heir, to support John’s claim and ‘if the king should die…should promote him to the kingdom with all his power.’6

Especial mention was made of Gerard de Camville, who was reinstated to Lincoln Castle, and ‘shall be reinstated in the office of sheriff of Lincoln, and on the same day a proper day shall be appointed for him to make his appearance in the court of our lord the king, there to abide his trial; and if in the judgement of the court of our lord the king proof can be given that he aught to lose that office as also the keepership of the castle of Lincoln, then he is to lose the same; but, if not, he is to keep it, unless in the meantime an agreement can be come to relative thereto on some other terms. And the lord John is not to support him against the decision of our lord the king, nor is he to harbour such outlaws or enemies to our lord the king, as shall be named to him, nor allow them to be harboured on his lands.’7

So, Gerard and Nicholaa would be safe in their castle at Lincoln, at least for now. What may happen on the king’s return was still to be determined. They also benefited from John’s largesse; Gerard was appointed keeper of the honour of Wallingford.

In the meantime, Nicholaa and Gerard could get on with the business of managing Lincoln Castle and the county of Lincolnshire.

For now…

Notes:

- Richard of Devizes, The Chronicle of Richard of Devizes, edited and translated by J. A. Giles

- ibid

- Roger of Howden (Hoveden), The Annals of Roger of Howden, translated by Henry T. Riley

- Devizes, The Chronicle of Richard of Devizes

- ibid

- ibid

- Howden, The Annals of Roger of Howden

Sources:

Richard of Devizes, The Chronicle of Richard of Devizes; Roger of Howden (Hoveden), The Annals of Roger of Howden; The Plantagenet Chronicles edited by Elizabeth Hallam; Brassey’s Battles by John Laffin; 1215 The Year of Magna Carta by Danny Danziger & John Gillingham; The Life and times of King John by Maurice Ashley; The Plantagenets, the Kings Who Made England by Dan Jones; England Under the Norman and Angevin Kings by Robert Bartlett; lincolnshirelife.co.uk; catherinehanley.co.uk; magnacarta800th.com; lothene.org; lincolncastle.com; The Sheriff: The Man and His Office by Irene Gladwin; Louise Wilkinson, Women in Thirteenth Century Lincolnshire; Richard Huscraft, Tales from the Long Twelfth Century; J.W.F. Hill, Medieval Lincoln; swaton.org.uk; oxforddnb.com; Ingulph, Ingulph’ Chronicle of the Abbey of Croyland; Stephen Church, King John: England, Magna Carta and the Making of a Tyrant; Marc Morris, King John; Pipe Rolls; Red Book of the Exchequer

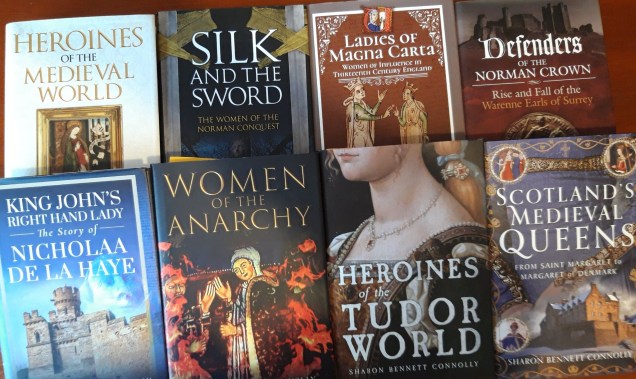

My Books:

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available, please get in touch by completing the contact me form or through my online bookshop.

Out now: Scotland’s Medieval Queens

Scotland’s history is dramatic, violent and bloody. Being England’s northern neighbour has never been easy. Scotland’s queens have had to deal with war, murder, imprisonment, political rivalries and open betrayal. They have loved and lost, raised kings and queens, ruled and died for Scotland. From St Margaret, who became one of the patron saints of Scotland, to Elizabeth de Burgh and the dramatic story of the Scottish Wars of Independence, to the love story and tragedy of Joan Beaufort, to Margaret of Denmark and the dawn of the Renaissance, Scotland’s Medieval Queens have seen it all. This is the story of Scotland through their eyes.

‘Scotland’s Medieval Queens gives a thorough grounding in the history of the women who ruled Scotland at the side of its kings, often in the shadows, but just as interesting in their lives beyond the spotlight. It’s not a subject that has been widely covered, and Sharon is a pioneer in bringing that information into accessible history.’ Elizabeth Chadwick (New York Times bestselling author)

Available now from Amazon and Pen and Sword Books

Also by me:

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. Heroines of the Tudor World is now available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how Empress Matilda and Matilda of Boulogne, unable to wield a sword themselves, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It shows how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other. Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org. Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

*

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell and Elizabeth Chadwick, and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved. In episode 15, Derek Birks and I discuss Nicholaa’s remarkable story:

There are now 80 episodes to listen to!

Every episode is also available on YouTube.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter, Threads, Bluesky and Instagram.

*

©2023 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS