When Henry VIII decided to break with Rome, he was making that decision not just for himself but for his entire nation. But Henry was still a conservative Catholic and while others embraced the Reformation and the tenets of Calvinism or Lutheranism, Henry remained Catholic to his dying day, just not Roman Catholic. His break with Rome led to the Dissolution of the Monasteries, where monastic institutions and communities were broken up and sold off.

This, in turn led to the Pilgrimage of Grace, a popular revolt in Yorkshire in October 1536, led by Robert Aske, which spread to other parts of northern England. The rebellion was inspired by the failed Lincolnshire Rising, which had started on 1 October 1536 and it was said 22,000 people followed a monk and shoemaker, the vicar of Louth and Nicholas Melton (known as Captain Cobbler) to protest against the closing of the monasteries and the seizure of church land and plate. The figure was probably much smaller, perhaps some 3,000 rebels. However, by the time they marched on Lincoln and occupied Lincoln Cathedral, some 40,000 rebels were demanding the right to worship as Roman Catholics and protection for the treasures of Lincolnshire’s churches. The Rising was all but over by 4 October, when Henry sent word that the protesters should disperse or face retribution at the hands of Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, who had mobilised his troops to put down the revolt.

By 14 October, most of the host had returned home. The two ringleaders were hanged at Tyburn, while other leading rebels were executed in the following days. It was against this background and the fear that the Rising must have invoked throughout Lincolnshire, that Anne Askew came to the fore. Anne Askew, also spelt Ayscough or Ainscough, was born around 1521, probably at the family home at Stallingborough, near Grimsby in Lincolnshire. She was the daughter of Sir William Askew and his first wife, Elizabeth Wrottesley.

Anne was the second oldest of five children, with an older sister Martha, a younger sister Jane, and two younger brothers, Francis and Edward. Her father, a landowner in Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire, was knighted in 1513. He attended the king at the Field of the Cloth of Gold in France in 1520 and in 1521 he was appointed High Sheriff of Lincolnshire. From 1529, he was a member of Parliament for Grimsby. After the death of Anne’s mother, he married twice more. He married the daughter of a Struxley or Streichley of Nottinghamshire, whose name is sadly now lost to history and married again in 1522 to Elizabeth, the daughter of John Hutton of Tudhoe, Co. Durham and the widow of Sir William Hansard of South Kelsey, Lincolnshire, with whom he had two more sons, Christopher and Thomas.

By about 1523, the family had moved to South Kelsey, just 20 miles from Lincoln. Anne was well educated, possibly by tutors, though we do not know the specifics of her education. Anne’s writings were published posthumously by reformist scholar John Bale, and it is from these that we get most of her story.

Anne’s future was decided following the tragic early death of her older sister, Martha. Sir William had arranged for Martha to marry Thomas Kyme of Friskney, the son and heir of a neighbouring landowner. Sadly, Martha died before the wedding could take place. Rather than suffer a financial loss with the failure of the arrangement, Sir William offered 15-year-old Anne as a replacement bride, ‘so that in the ende she was compelled against her will or fre consent to marrye with hym,’ and, as John Bale put it, Anne ‘demeaned her selfe lyke a Christen wife’.1 Anne and Thomas had two children together.

It was about the time that Anne was preparing for her wedding, in 1536, that the Lincolnshire Rising erupted, starting in Louth and making its way towards Lincoln. Her father Sir William was one of the commissioners for the king’s tax subsidy who were due to sit in Caistor as the rebels arrived in the town. Sir William attempted to ride for home, ahead of the rebellious host. He was soon captured, aware that his own servants who were accompanying him supported the rebels. Anne’s brothers were also arrested by the rebels and their house watched. Sir William was then forced to write to the king to inform him of what had happened, with the complaint that ‘the common voice and fame was that all jewels and goods of the churches of the country should be taken from them and brought to Your Grace’s Council, and also that your said loving and faithful subjects should be put off new enhancements and other importunate charges.’2

With the failure of the rebellion, Sir William and his sons returned home. One wonders if the treatment of her menfolk, at the hands of those who were defending Roman Catholicism, was not a factor in Anne turning to the reformed faith. However the transformation came about, and in spite of her husband’s devout Catholicism, Anne did become a committed Protestant. She acquired a copy of an English Bible and began reading aloud from it, though her husband and brother had both forbidden her to do so. Anne explained that ‘in processe of tyme by oft reading of the sacred Bible, she fell clerelye from all olde superstycyons of papystrye, to a perfyght believe in Jhesus Christ.’3

In May 1543, the Act for the Advancement of True Religion was passed, forbidding any woman below the rank of noblewoman or gentlewoman from reading the Bible; and forbidding any woman, of any rank, from reading the Bible aloud. Anne was a gentlewoman and therefore still permitted to read the Bible, but only in private. She wanted to travel to Lincoln to see the cathedral’s Bible, but Kyme forbade it. Anne had been apprised of the hostility this would engender: ‘For my fryndes told me, if I ded come to Lyncolne, the prestes wolde assault me and put me to great trouble, as thereof they had made their boast.’4 Anne did travel to Lincoln and stayed there for about six days, reading her Bible in the cathedral. She said that one man confronted her, but he had said so little of significance that she could not recall his words.

This incident, and the fact that Anne continued to read aloud to whoever would listen, to such an extent that the local priest complained to her husband, infuriated Thomas Kyme. Angry and embarrassed at his wife’s actions, Kyme drove her from the house, with some violence. Driven from hearth and home – and from her children, Anne resumed her maiden name and sought a divorce. In late 1544 she travelled to London, accompanied by only a maid, in order to obtain a legal separation in the court of chancery. Two of her brothers were already in London. Edward, who had previously been in the service of Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, was cup-bearer to Henry VIII and her half-brother, Christopher, who died around this time, was a Gentleman of the Privy Chamber.

Her cousin, Christopher Brittayn, was a lawyer at the Temple and Anne’s sister Jane was married to George St Poll, a lawyer in the service of the duke and duchess of Suffolk. Anne lodged in a house close to the Temple, London’s legal centre, and soon met others with like-minded religious views, many with connections. Several gentlewomen gave Anne money, including the countess of Hertford and the wife of Sir Anthony Denny. They both sent messengers to Anne with money.

Anne found herself moving in exalted circles, these ladies were close friends of Henry VIII’s new queen, Kateryn Parr, though whether the queen and Anne ever met is uncertain. Anne made other connections in the city, including her religious advisor John Lascels and the chronicler Edward Hall. She was also close to the Kentish Anabaptist Joan Bocher, who would be executed in 1550.

After preaching publicly in the streets of the capital, Anne came to the attention of the authorities. According to Anne’s nephew, writing after her death, she was arrested following the interception of a letter she was trying to send, while attempting to communicate with the queen. She was detained on 10 March 1545, under the Six Articles Act, which made deviation from the official tenets of the English church a civil offence. Anne was brought before Sir Martin Bowes, Lord Mayor of London, and the bishop of London’s chancellor, and interrogated as to her beliefs. She was told that St Paul forbade women from talking of the word of God, but Anne countered that St Paul only barred women from instructing a congregation.

Still only 24 years of age, Anne was confident, fearless and bold in dealing with the great men of the city of London. Women were not meant to behave in such a way, they were supposed to be contrite and accept the superior intellect and authority of the men in charge. As a consequence, the Lord Mayor ordered her imprisonment. She spent 12 days in prison, visited daily by a priest sent by Edmund Bonner, Bishop of London. Her cousin, Brittayn, failed in his petition to have her released on bail, but succeeded in having her examined before the bishop himself, on 25 March. She was accused of subscribing to reformist beliefs concerning transubstantiation and the other sacraments and the dominion of the priesthood and asked to sign a declaration of orthodox faith.

Anne took the paper and wrote ‘I, Anne Askewe do beleve all maner thynges contayned in the faythe of the Catholyck churche.’5 Bishop Bonner flew into a fury, but her cousin, Brittayn, persuaded him that she acted from her ‘weak woman’s wit’ and with the added voices of her friends, Hall, Hugh Weston and Francis Spilman, Anne was returned to prison for one more night before being freed on bail the next day. Whether or not Anne abjured is open to interpretation; the authorities say she did, Anne denied it.

Once freed, Anne continued to pursue her divorce from Thomas Kyme. The Privy Council became involved and ordered both Anne and Thomas to appear before them within ten days. Anne and Kyme were brought before the Council at Greenwich and were questioned about their relationship. The questioning, under the direction of Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester, turned to the matter of Anne’s views in the sacrament and after an exchange of words whereby Anne evaded Gardiner’s questions, she was again committed to prison for the night, this time to Newgate, a harrowing place. Kyme returned home. Anne was brought before the Council the next day and questioned further by Bishop Gardiner, who declared that she should be burnt.

According to Anne herself, they charged her ‘upon my obedience to show them if I knew any man or woman of my sect. Answered that I knew none. Then they asked me of my lady of Suffolk, my lady of Sussex, my lady of Hertford, my lady Denny and my lady Fitzwilliam.’6 These women were close associates of the queen, Kateryn Parr. The queen’s chambers were searched for heretical texts, though none were found.

On 28 June 1546, Anne Askew was arraigned for heresy at the Guildhall in London, alongside Nicholas Shaxton, former Bishop of Salisbury, and two other men. Shaxton abjured but Anne was condemned ‘without any triall of a jurie’.7

The next day, Anne was sent to the Tower and subjected to further questioning. It was hoped that this would force Anne to reveal her associates at court and, by extension, their husbands. When she refused to name anyone, her interrogators, Thomas Wriothesley and Richard Rich, took the exceptional step of having her undress to her shift and fastened to the rack. In Anne’s own words:

Then they put me on the rack because I confessed no ladies or gentlewomen to be of my opinion; and there they kept me a long time, and because I lay still and did not cry, my lord chancellor and Master Rich took pains to rack me with their own hands till I was nigh dead. Then the lieutenant (of the Tower) caused me to be loosed from the rack. Immediately, I swooned away, and then they recovered me again. After that I sat two long hours reasoning with my lord chancellor upon the bare floor.8

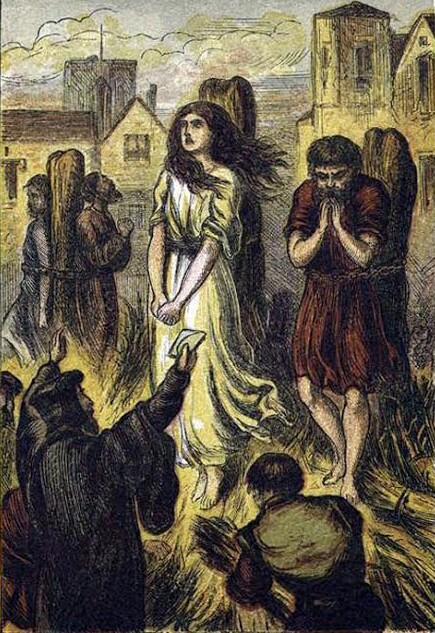

As a woman, gently born and already condemned, Anne should have been exempt from such treatment. Anne was so severely tortured that by the end of it her body was broken, all four limbs were dislocated and she was unable to stand. She was eventually returned to Newgate from where, on 16 July 1546, Anne was carried to the site of her execution at Smithfield, sat on a chair in a cart, every movement causing her more pain. She was tied to another chair at the stake, where she was given one more chance to recant and receive a pardon.

She refused.

She died alongside three other Protestants, John Lascels, John Hadlam, who was a tailor, and John Hemley, formerly an Observant friar.

Anne Askew holds the terrible distinction of being one of only two women to have ever been tortured in the Tower of London, the other being Margaret Cheyne, who had been involved in the Pilgrimage of Grace and was also burnt for heresy. Anne died bravely, never revealing her connections at court, thus, perhaps, saving a queen of England from the same fate. She was 25 years old.

On a national level, her death was a consequence of the growing fear that accompanied Henry’s failing health. On a personal level, although Anne’s journey to London had arisen from her marriage troubles, these troubles were always entwined within her own spiritual journey. Anne’s supreme confidence in her faith and her courage under torture deservedly earned her a place in the Protestant martyrology. Her own, first-hand account of her story was edited and published by John Bale and reprinted in John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, ensuring her legacy would pass down through the generations.

*

Notes:

1. The examinations of Anne Askew, edited by E. V. Beilin, quoted in Diane Watt, ‘Askew [married name Kyme], Anne’, Oxforddnb.com; 2. & P, Vol XI, p. 534, quoted in Elizabeth Norton, The Lives of Tudor Women; 3. The examinations of Anne Askew, edited by E. V. Beilin, quoted in Diane Watt, ‘Askew [married name Kyme], Anne’; 4. ibid; 5. ibid; 6. The examinations of Anne Askew, quoted in Amy Licence, The Sixteenth Century in 100 Women; 7. Thomas Wriothesley quoted in Diane Watt, ‘Askew [married name Kyme], Anne’; 8. Mickey Mayhew, House of Tudor: A Grisly History

Sources:

Diane Watt, ‘Askew [married name Kyme], Anne’, Oxforddnb.com; Amy Licence, The Sixteenth Century in 100 Women; The examinations of Anne Askew, edited by E. V. Beilin; Elizabeth Norton, The Lives of Tudor Women; Don Matzat, Katherine Parr: Opportunist, Queen, Reformer; Mickey Mayhew, House of Tudor: A Grisly History; J.D. Mackie, The Earlier Tudors 1485-1558; Arthur D. Innes, A History of England Under the Tudors; Sarah Bryson, The Brandon Men: In the Shadow of Kings; Steven Gunn, Charles Brandon: Henry VIII’s Closest Friend; Sarah Bryson, La Reine Blanche: Mary Tudor, A Life in Letters; John Paul Davis, A Hidden History of the Tower of London: England’s Most; Robert Lacey, The Life and Times of Henry VIII; David Loades, editor, Chronicles of the Tudor Kings: The Tudor Dynasty from 1485 to 1553: Henry VII, Henry VIII and Edward VI in the Words of their Contemporaries.

Images:

Courtesy of Wikipedia except Lincoln Cathedral which is ©2024 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS

*

My Books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

Out now: Scotland’s Medieval Queens

Scotland’s history is dramatic, violent and bloody. Being England’s northern neighbour has never been easy. Scotland’s queens have had to deal with war, murder, imprisonment, political rivalries and open betrayal. They have loved and lost, raised kings and queens, ruled and died for Scotland. From St Margaret, who became one of the patron saints of Scotland, to Elizabeth de Burgh and the dramatic story of the Scottish Wars of Independence, to the love story and tragedy of Joan Beaufort, to Margaret of Denmark and the dawn of the Renaissance, Scotland’s Medieval Queens have seen it all. This is the story of Scotland through their eyes.

‘Scotland’s Medieval Queens gives a thorough grounding in the history of the women who ruled Scotland at the side of its kings, often in the shadows, but just as interesting in their lives beyond the spotlight. It’s not a subject that has been widely covered, and Sharon is a pioneer in bringing that information into accessible history.’ Elizabeth Chadwick (New York Times bestselling author)

Available now from Amazon and Pen and Sword Books

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. Heroines of the Tudor World is now available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how Empress Matilda and Matilda of Boulogne, unable to wield a sword themselves, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It shows how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other. Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org. Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell and Elizabeth Chadwick, and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

There are now over 70 episodes to listen to!

Every episode is also now available on YouTube.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter, Threads, Bluesky and Instagram.

©2024 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS