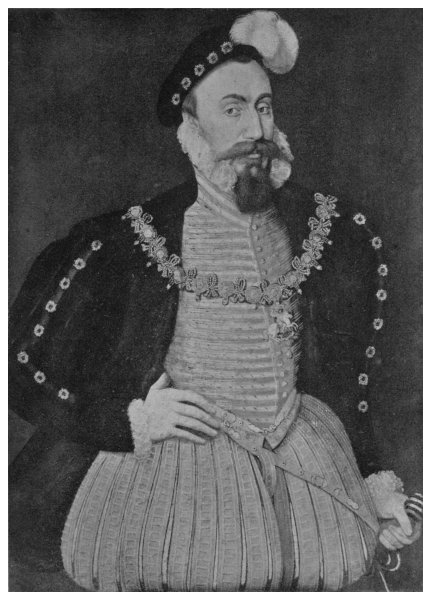

Frances and Henry Grey were married in 1533, at her parent’s residence of Suffolk Place in Southwark. As the eldest surviving child of Mary Tudor, dowager Queen of France and Duchess of Suffolk, Frances was fourth in line to the throne after the children of Henry VIII, Edward, Mary and Elizabeth. When settling the succession, the king had instructed that his younger sister Mary’s line should be preferred over that of his older sister, Margaret. As a consequence, Frances was frequently at court.

The couple’s first child, a son, died young. They had three surviving daughters. The eldest, Jane, was born in October 1537, about the same time as her cousin Edward, the future King Edward VI; with the birth of the longed-for heir to the throne, Jane’s own birth went almost unnoticed. Jane would have been named after Henry VIII’s tragic queen, Jane Seymour, who died within two weeks of Edward’s birth.

Jane Grey would be known to history as the Nine Days’ Queen.

She was raised at the family home of Bradgate Park, near Leicester. Frances and Henry Grey are said to have been very strict parents who were not prone to expressions of love and affection; the children were used to sarcasm, cuffs and criticism. In her teenage years, Jane herself is said to have complained to the visiting scholar Roger Ascham:

‘When I am in the presence either of father or mother, whether I speak, keep silence, sit, stand or go, eat, drink, be merry or sad, be sewing, playing, dancing, or doing anything else, I must do it as it were in such weight, measure and number, even so perfectly as God made the world; or else I am so sharply taunted, so cruelly threatened, yea presently sometimes with pinches, nips and bobs and other ways (which I will not name for the honour I bear them) … that I think myself in hell.’1

Jane enjoyed study and excelled in all fields, including Greek and philosophy. She was afforded a first-class education and from 1545 her tutor was John Aylmer. Aylmer had been sponsored through his studies at Cambridge by Jane’s father, the Marquess of Dorset, and was a brilliant academic. As a future courtier, Jane was given lessons in dance and music; probably including the popular instruments, the lute, spinet and virginal. In religion, Jane and her sisters were raised as ‘evangelicals’, the common word in the first half of the sixteenth century for Protestants. From the age of nine, Jane’s mother would have taken her to court from time to time, to familiarise her daughter with the court and her future duties as a Maid of Honour. Frances was at the time serving as a Lady of the Privy Chamber to the king’s sixth wife, Kateryn Parr, Henry VIII’s 6th and final wife.

In January 1547, King Henry VIII died and was succeeded by his 9-year-old son, Edward VI. Jane and Edward were first cousins, once removed,and it is entirely possible – even likely – that Frances and Henry harboured hopes that Jane would marry the young king. It was Henry VIII’s will that shaped and dominated Jane’s future. More than ten years before his death, Parliament had granted Henry the right to bequeath the crown where he desired, rather than by strict primogeniture. In his final will, dated 26 December 1546, Henry excluded the Stuart line of his elder sister Margaret and settled the succession, should his children die without heirs, on the descendants of his younger sister, Mary, Duchess of Suffolk. Should Edward, Mary and Elizabeth all die without producing a child of their own, Jane would be queen; although Henry probably still held out hope that Frances would produce a son who could inherit ahead of the sisters.

The government of England was now in the hands of the boy-king’s uncle Edward Seymour, Earl of Somerset – soon to become duke of Somerset. Somerset and Henry Grey did not get along well and Grey, though he was the only marquess in England he was not appointed to the new king’s privy council. The younger brother of Somerset, Thomas Seymour, the Lord High Admiral of England and first Baron Seymour of Sudeley, having recently – and rather scandalously – married the king’s widow, proposed that he take on the wardship of Lady Jane. Henry Grey was reluctant, given the scandal attached to the hasty marriage of Queen Kateryn and Seymour just four months after the king’s death. However, Princess Elizabeth had already joined the dowager queen’s household and Seymour hinted at arranging a marriage between Jane and the young king when they were old enough, sweetening the deal with the offer of a payment of £2,000 for Jane’s wardship.

Joining the household of the dowager queen was a great opportunity for Jane, which would provide her with connections that would benefit herself and her family. And so, at ten years-old, Jane was given into the custody of Thomas Seymour and from then on was frequently in the household of Kateryn Parr, at Chelsea and later at Sudeley Castle. This was one of the happiest periods of Jane’s short life.

During her time in the dowager queen’s household, Jane got to know her cousin, Princess Elizabeth, better, though they never grew close. At thirteen, Elizabeth was too old to pay much attention to ten-year-old Jane. And despite her tender years, Elizabeth was rather self-contained and distant; she had already experienced the highs and lows of royal life, from being lauded as her father’s heir to being declared a bastard and knowing her mother was executed as a traitor. The princess had learned not to trust easily and to keep her own counsel. That Jane was, technically, Elizabeth’s heir, must have made the relationship more fractious in a world where one’s inheritance could be erased by an act of parliament.

Jane must have enjoyed living in a household of well educated, inquisitive women. One wonders, though, if she was aware of other goings-on in the household, as Thomas Seymour paid excessive attention to Princess Elizabeth. This caused tensions within the household, especially after the queen fell pregnant and began to fear that Seymour saw Elizabeth as a suitable replacement should she die in childbirth. Fearful for the princess’s reputation – and of her husband’s intentions – Elizabeth was sent away by Kateryn. Jane was now the most senior lady in the queen dowager’s household. And when Kateryn died a week after giving birth to her only child, Lady Mary Seymour, it was 11-year-old Jane who acted as chief mourner at her funeral, walking behind the queen’s coffin from the house to the chapel at Sudeley.

After the funeral, the queen’s household was broken up and Jane sent home to her parents. Within a few weeks, however, Thomas Seymour, now over the first stages of grief at losing his wife, given the blow to his finances and status the queen’s death had caused, realised that he could yet regain some standing if he resumed his guardianship of Jane. It took some persuading, but Seymour assured Henry and Frances that Jane would be well cared for and under the supervision of his mother. Although the late dowager queen’s women were still in Seymour’s household, the atmosphere had changed; and as Seymour’s ambitions came under suspicion from the Privy Council, it must have been an uncomfortable place for Jane to be. Amid rumours that Thomas Seymour was intending to marry Princess Elizabeth, he was arrested, as were Elizabeth’s servants. Elizabeth herself continued to insist that she would never agree to marry anyone without the Council’s permission.

Seymour was condemned for high treason by Act of Attainder and executed on 20 March 1549. On Seymour’s arrest, Jane had returned to Dorset House, her family’s London residence. Henry Grey may have seen his own hopes of advancement and Jane’s marriage to Edward VI disappear at Seymour’s arrest, but he must have been relieved that at least he had survived the affair with his head still on his shoulders. Besides, the wheel of fortune was about to turn his way. People were becoming increasingly disenchanted with Somerset’s rule and in the wake of Kett’s Rebellion in Norfolk, by 14 October it was Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, who was lodged in the Tower under arrest. John Dudley, Earl of Warwick and future Duke of Northumberland, took the reins of government. Henry Grey was finally appointed to the Privy Council and received numerous rewards of office and grants of lands and lordships.

Jane’s marriage was never far from the minds of those in power. Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset had wanted to marry Jane to his oldest son and heir, the earl of Hertford, also called Edward. Nothing had come of this plan by the time of Somerset’s fall. Before that, as early as 1541, the French Ambassador had proposed that she marry Charles, Duke of Orléans, third son of King Francis I, but the boy died in 1545. John Dudley initially favoured a marriage between Jane and the king. The children born of such a marriage would secure the succession and guarantee the continuance of the new religion within England’s borders. It would also resolve the problems associated with the succession of Mary or Elizabeth. Jane and Edward were good friends and corresponded regularly, but neither Jane nor Edward appeared enthusiastic about the suggestion and the idea was dropped, for the time being.

By February of 1553, the point was moot.

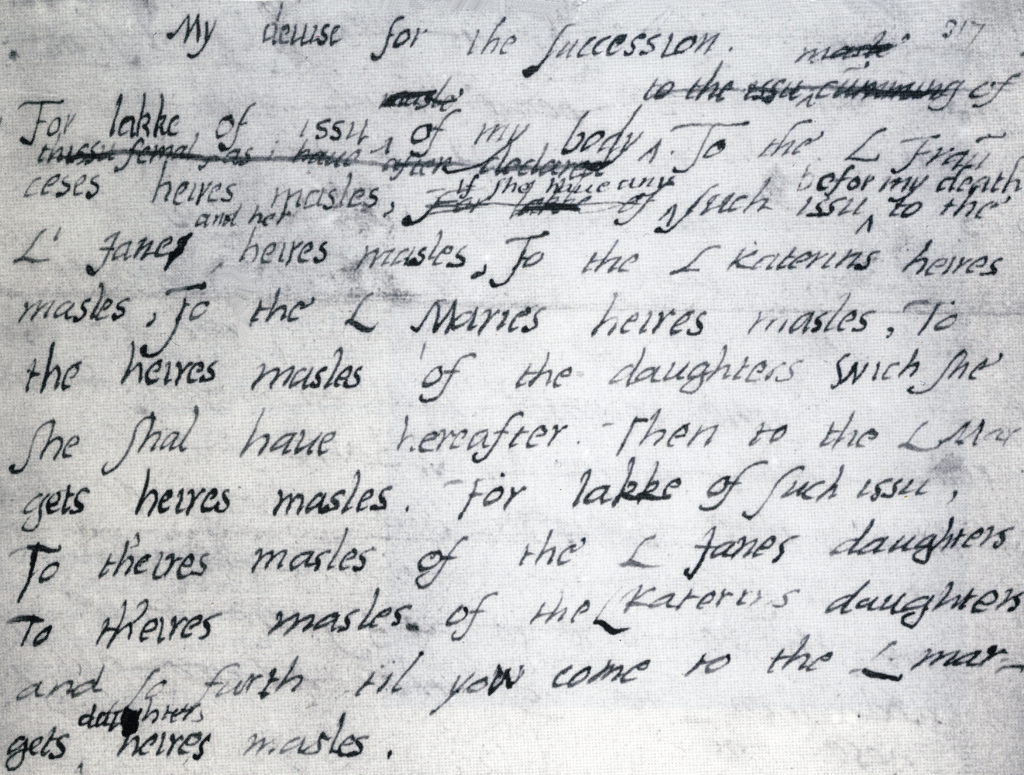

The young king was ill again, and it was becoming apparent that he was dying. Those around him started looking to the problem of the succession. The next in line was Princess Mary, a committed Catholic who would undo all the work Edward had done in advancing the Reformation. Edward could not pass over Mary’s claim to the crown in favour of Elizabeth, so chose to exclude all females from the succession and his ‘Device’ would leave the crown to ‘the Lady Jane’s heirs male’. As his health failed him, in June King Edward changed the wording of the Device to ‘The Lady Jane and her heirs male.’ Further arguments for excluding Mary and Elizabeth centred on their legitimacy – open to question after Henry VIII had, at various times, declared them both illegitimate – and the fear that they would marry outside of England.

Jane, on the other hand, was married to Lord Guildford Dudley, the fifteen-year-old son of John Dudley, now Duke of Northumberland and Lord President of the Council. Their parents saw the young couple as an alternative, Protestant king and queen to the Catholic Mary. The wedding had taken place in May 1553 in Dudley’s London home, Durham House. The young couple had been reluctant to marry and were bullied into it by their parents.

Aged just fifteen, King Edward VI died at Greenwich Palace on 6 July 1553. He was unmarried and left no heir. As the king lay dying Mary was summoned to the council, but instead rode to Kenninghall in Norfolk, with Robert Dudley despatched to intercept her with orders to take the princess to a place of safety. On 8 July, Mary heard the news of the king’s death and the following day proclaimed herself queen, despatching a letter to the Privy Council, ordering them to endorse her claim. She then moved to the formidable fortress of Framlingham Castle, where thousands flocked to her standard. Princess Elizabeth initially stayed away, pleading illness, watching and waiting to see how events played out. On 9 July the Privy Council summoned Lady Jane, recuperating from an illness at Chelsea, to appear before them. Dudley’s daughter, Mary Sidney, was sent to escort Jane by barge to Syon House, where she was greeted by two nobles who knelt before her, kissed her and informed her that Edward had nominated her as his successor. John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland and now father-in-law of the new queen, gave a lengthy speech, informing all present that King Edward’s wish had been for Jane to succeed him. Jane was left trembling and speechless before she fell to the ground, crying and declaring

I am insufficient to fill the role.2

Jane’s reaction to the proclamation of her accession to the throne suggests that she was not aware of the plans of Edward, Dudley and her father to make her queen. Though she was a clever girl and may well have suspected what was afoot. The next morning, dressed in the green and white of the Tudors and accompanied by her husband Guildford dressed equally splendidly in white and gold, Jane was escorted to the Tower in a procession of barges. There were no flags being waved, and no crowds lining the river to get a glimpse of their new queen. London was only just learning of the king’s death. Jane was greeted at the Tower by the Marquess of Winchester and Sir John Bridges, Lieutenant of the Tower, and various other civilian and military officials. Winchester knelt before the young queen and presented the keys to the fortress. John Dudley stepped forward and took them. Jane then made her ceremonial entrance into the White Tower and, with flags flying, a fanfare of trumpets and guns firing in salute, was seated under the canopy of state. The crown was brought to her, but she initially refused to wear it, only putting it on when Winchester persuaded her that he wished to see how it suited her.

On one matter, Jane was adamant. She refused to make Guildford king: ‘If the crown belongs to me, I would be content to make my husband a duke. But I will never consent to make him king.’3 Royal blood flowed through Jane’s veins, not her husband’s. Apparently, Guildford fled the room in tears, but his parents were hopeful that Jane could be persuaded to change her mind. After all, they lived in a patriarchal society and no one expected that a woman could actually rule in her own right.

The Privy Council and leading judges declared Jane the new Queen of England.

That Sunday, at St Paul’s Cross, Bishop Ridley preached that as bastards, Mary and Elizabeth were unfit for the crown and that Mary’s Catholicism was a particular threat to the country, exposing it to foreign influence. A devout Protestant, Jane was seen as the symbol of continuity for the Protestant faith, untainted by any previous declarations of illegitimacy. However, there was no rejoicing and only the herald could be heard to shout ‘Long live the Queen!’

For 9 days, Jane was England’s first female monarch.

By 12 July, Mary and her supporters had gathered at Framlingham, Suffolk. Within days, the duke of Northumberland rode out of London with 3,000 men, promising to capture or kill Mary. Jane ordered the gates to the Tower be locked and the keys given to her. On 18 July, Jane began raising troops to be led against rebels in Buckinghamshire. But as Northumberland left London, everything began to fall apart. Rumours circulated that Mary had a force of 30,000. Londoners refused to rally to the duke’s army.

Northumberland’s coup collapsed.

On 19 July, Henry Grey, Duke of Suffolk, declared in favour of Mary. He entered his daughter’s chamber, where she sat at dinner under a canopy of state, and dramatically tore down the hangings. The next day, the Privy Council proclaimed Mary as Queen of England. And Jane went from being queen to a prisoner in the Tower of London; she was taken from the royal apartments to the Gentleman Gaoler’s lodgings. Her mother and ladies-in-waiting were allowed to return home, which they did without delay.

Mary was crowned on 1 October 1533, and Jane’s younger sisters Katherine and Mary became maids of honour to the new queen. Frances, too, was welcomed at court. John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, Jane’s father-in-law, had been tried and convicted of high treason and executed on 22 August 1553. After just a few days in the Tower, Henry Grey, Duke of Suffolk, was pardoned and allowed to go home to his wife.

As for Jane, in November, she, her husband and two of his brothers were tried and convicted of high treason. Mary was willing to be merciful and spared their lives, for the moment. Jane was kept in comfortable confinement and may have hoped that she would eventually be released, had her father not involved himself in yet another plot…

Opposed to Mary’s proposed marriage to Philip of Spain, the Wyatt rebellion, led by Sir Thomas Wyatt, the son of the poet who was an admirer of Anne Boleyn, aimed to overthrow Mary. The intent was to marry Princess Elizabeth to Edward Courtney, Earl of Devon and a descendant of Edward IV, and put Elizabeth on the throne. As Wyatt raised an army in Kent, Grey was raising forces in the Midlands. However, Wyatt’s forces were overwhelmed as London closed its gates to them and Grey was arrested at his manor of Astley. He was taken prisoner, arraigned for his treason, condemned, and executed at the Tower on 23 February 1554, less than a month after his brief rebellion began.

Though she was in no way implicated in the rebellion, her father’s actions had already sealed Jane’s fate; her very existence as a possible figurehead for Protestant discontent made her an unacceptable danger to the state. The queen could no longer afford to be merciful, and Mary signed the death warrant for Jane and Guildford; the sentence for Jane was commuted from burning to beheading. She received a few days’ stay of execution while Mary sent the dean of St Paul’s, John Feckenham, to her to try and persuade Jane to accept the Catholic faith. But Jane remained steadfast, writing ‘Lord, thou God and father of my life, hear me poor and desolute woman, arm me, I beseech thee, with thy armour, that I may stand fast.’4

The night before her execution, aware that her father, by now also imprisoned in the Tower, was in great distress over her fate, Jane wrote a final letter to him:

‘Father, although it pleases God to hasten my death by one by whom my life should rather have been lengthened; yet can I so patiently take it, that I yield God more hearty thanks for shortening my woeful days, than if all the world had been given into my possession, with life lengthened at my own will. And albeit I am assured for your impatient dolours redoubled manifold ways, both in bewailing your own woe, and especially, as I hear, my unfortunate state; yet, dear father (if I may without offence rejoice in my own mishaps), herein I may account myself blessed, that washing my hands with the innocence of my fact, my guiltless blood may cry before the Lord, ‘Mercy to the innocent!’5

At ten the next morning Guildford Dudley was taken from the Tower and escorted to Tower Hill for his execution. Jane watched him leave from her window. As Jane walked to her own execution, Guildford’s body was carried into the Tower’s chapel, St Peter Ad Vincula, for burial. Dressed in black, Jane mounted the scaffold by the White Tower. Speaking to the assembled crowd, she performed the traditional admission of guilt, saying that she had acted against the queen’s highness, though qualified it with:

‘Touching the procurement and desire thereof by me or on my behalf, I do wash my hands thereof in innocence.’6

Having said her piece, and her prayers, Jane gave her gloves and handkerchief to Elizabeth Tilney and her prayer book to Thomas Bridges, the brother of the Lieutenant of the Tower. Jane then removed her gown, headdress and neckerchief as the executioner knelt to ask her forgiveness, which Jane gave willingly.

Jane knelt and, with her handkerchief tied over her eyes, she had to feel for the block and cried out ‘What shall I do? Where is it?’ when she couldn’t find it.7 One of those close by guided her to the block.

Her final words were ‘Lord, into thy hands I commend my spirit!’8

She was despatched with one stroke of the axe.

Notes:

1 .Lady jane Grey quoted in Jill Armitage, Four Queens and a Countess: Mary Queen of Scots, Elizabeth I, Mary I, Lady Jane Grey and Bess of Hardwick, p. 54; 2. Jill Armitage, Four Queens and a Countess: Mary Queen of Scots, Elizabeth I, Mary I, Lady Jane Grey and Bess of Hardwick, p. 68; 3. ibid; 4. Leanda de Lisle, The Sisters Who Would Be Queen, p. 146; 5. ibid, p. 148; 6. ibid, p. 150; 7. ibid, p. 151; 8. ibid, p. 152

Images:

Courtesy of Wikipedia

Sources:

Jill Armitage, Four Queens and a Countess: Mary Queen of Scots, Elizabeth I, Mary I, Lady Jane Grey and Bess of Hardwick; Leanda de Lisle, The Sisters Who Would Be Queen; Amy Licence, Tudor Roses; Amy Licence, The Sixteenth Century in 100 Women; Haynes (ed.), State papers, Vol. VI; Amy Licence, In Bed with the Tudors; Erin Lawless, Forgotten Royal Women: The King and I; David Loades, editor, Chronicles of the Tudor Kings: The Tudor Dynasty from 1485 to 1553: Henry VII, Henry VIII and Edward VI in the Words of their Contemporaries; ODNB.com; Tracy Borman, The Private Lives of the Tudors; Sarah Gristwood, The Tudors in Love: The Courtly Code Behind the Last Medieval Dynasty; John Cannon, editor, The Oxford Companion to British History; Arthur D. Innes, A History of England Under the Tudors; J.D. Mackie, The Earlier Tudors 1485-1558

*

My Books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

OUT NOW! Heroines of the Tudor World

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. These are the women who made a difference, who influenced countries, kings and the Reformation. In the era dominated by the Renaissance and Reformation, Heroines of the Tudor World examines the threats and challenges faced by the women of the era, and how they overcame them. From writers to regents, from nuns to queens, Heroines of the Tudor World shines the spotlight on the women helped to shape Early Modern Europe.

Heroines of the Tudor World is now available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK.

Women of the Anarchy

Two cousins. On the one side is Empress Matilda, or Maud. The sole surviving legitimate child of Henry I, she is fighting for her birthright and that of her children. On the other side is her cousin, Queen Matilda, supporting her husband, King Stephen, and fighting to see her own son inherit the English crown. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how these women, unable to wield a sword, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It show how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other.

Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK.

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon. Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org.

Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell – and Tony Riches. We discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

*

©2024 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS