Alexander I was the second-to-youngest son of Malcolm III Canmore and his sainted wife Margaret of Wessex. Born around 1077 or 1078, he was thirty-or-so when he ascended the throne in 1107, ‘as the King Henry granted him.’1 Like his brother Edgar before him, Alexander succeeded to the throne as a vassal of the English crown. He had probably spent the years between his father’s death and Edgar’s accession in exile in England, with Edgar and their younger brother, David. John of Fordun provides a largely flattering assessment of Alexander I as king:

‘Now the king was a lettered and godly man ; very humble and amiable towards the clerics and regulars, but terrible beyond measure to the rest of his subjects; a man of large heart, exerting himself in all things beyond his strength. He was most zealous in building churches, in searching for relics of saints, in providing and arranging priestly vestments and sacred books; most open-handed, even beyond his means, to all newcomers; and so devoted to the poor, that he seemed to delight in nothing so much as in supporting them, washing, nourishing, and clothing them.’2

One of the primary duties of a king is to marry and produce heirs; at least one son, preferably two – the heir and the spare. This guarantees the succession and offers stability to a country. Even daughters were useful to a king, their marriages cementing alliances with friends and enemies alike. Alexander I was married shortly after his accession to the throne. His bride was offered to him by his brother-in-law, King Henry I of England. She was Sybilla, also known as Sybilla of Normandy, one of the King of England’s many illegitimate offspring.

King Henry had more than twenty illegitimate children and as many as five were by the same mother, his mistress, or concubine, Sybilla Corbet. Orderic Vitalis refers to Sybilla of Normandy as ‘the daughter of King Henry by a concubine’.3 It is highly likely that Sybilla Corbet was Sybilla’s mother, one indication being their shared Christian name. She was the daughter of a Shropshire landowner named Robert Corbet. Her children with the king included Reginald, Earl of Cornwall, and a young man named William, who was described as the queen’s brother when he accompanied the younger Sybilla to Scotland. Sybilla Corbet is also reputed to have been the mother of Robert, Earl of Gloucester, Henry I’s oldest son and the stalwart supporter of his legitimate sister, Empress Matilda, during the Anarchy. After the end of her relationship with the king, Sybilla Corbet would go on to marry Herbert FitzHerbert, who held lands in Yorkshire and Gloucestershire, and have a further five children.

The date of Alexander’s marriage to Sybilla is unknown, though it is thought to have been shortly after his accession to the throne, possibly in 1107 or 1108, and before his involvement in the English campaign in Wales in 1114. It was in a charter dated to 1114 or 1115 that Alexander and Sybilla jointly refounded Scone Abbey, whereby they are referred to as ‘Alexander … King of Scots, son of King Malcolm and Queen Margaret and … Sybilla, Queen of Scots, daughter of King Henry of England.’4

Another unknown is Sybilla’s age at the time of her marriage as her birth was unrecorded. Alexander was in his 30s, while most historians agree that it is likely that Sybilla was born in the mid-to-late 1090s and probably in her mid-teens. Although born out of wedlock, as the acknowledged daughter of King Henry I of England, Sybilla was considered a suitable wife for King Alexander. Henry I’s illegitimate daughters played an important role in his foreign and domestic policies; no fewer than ten of them were married into the upper classes of the Norman-French nobility to cement political alliances. Sybilla’s illegitimate status was of less significance than the fact her father was the King of England.

The marriage was intended to bind Alexander even closer to England and to King Henry personally, who was already his brother-in-law, having married Alexander’s sister, Matilda of Scotland, shortly after becoming king. The union was also aimed at securing peace along the Anglo-Scottish border. In his chronicle, William of Malmesbury recorded the marriage, though did not name Sybilla and added ‘there was … some defect about the lady either in correctness of manners or elegance of person.’5 Malmesbury stated that Alexander ‘did not sigh much when she died before him, for the woman lacked, as is said, what was desired, either in modest manners, or in elegant body’.6 Unfortunately, William of Malmesbury does not elaborate further on this defect, nor on the reasons behind such an unflattering description of the Scottish queen. No other chronicler mentions any flaws in the queen. It is possible that Malmesbury was playing down the queen’s attributes, and the impact of her death on the king, in order to find favour with her brother-in-law David, Alexander I’s younger brother and heir.

Some historians have interpreted the childless marriage as also being loveless, perhaps drawing on Malmesbury’s depiction of Sybilla, most actually agree that, although there were no children, it was a happy and loving marriage. With this distance of time, it would be difficult to be certain either way. However, despite the lack of an heir, Alexander did not repudiate his wife, though that could always be as a result of who her father was. Rosalind Marshal suggests that Alexander loved Sybilla, and mourned her deeply when she died, founding a church in her memory.

Alexander and Sybilla’s court is said to have been one of splendour, with reference to Arab stallions and Turkish men-at-arms. They issued a number of charters together, including the one founding Scone Abbey, mentioned above. Scone was the ancient site for the installation and crowning of Scotland’s kings, it was the centre of royal power in Scotland. Sybilla’s inclusion in the foundation of the Augustinian priory there demonstrates how she had become an integral part of the Scottish ruling dynasty. She and Alexander also made a joint offering to the cathedral church of St Andrews.

Sybilla also made grants, as an ecclesiastical patron, in her own right. She granted the manor of Beath in Fife to Dunfermline Abbey, the monastery founded by her husband’s parents, Malcolm III and Queen Margaret, their final resting place. Sybilla attested one of the four surviving charters from Alexander I’s reign, demonstrating her presence at court and involvement in the affairs of state. Significantly, it may have been Sybilla who acted as peacemaker between the king and Eadmer, when he became Bishop of St Andrews. Due to the investiture controversy that was causing issues throughout Europe, with kings and bishops in disagreement over the validity of lay investiture, Eadmer accepted the ring of office from King Alexander, but not the staff. The staff had been placed on the altar at the cathedral of St Andrews and it seems likely that Sybilla was the one who broached the compromise whereby Eadmer would take the episcopal ring from the king, but the pastoral staff from the altar. When Eadmer arrived at the cathedral church of St Andrews to take up the pastoral staff, Queen Sybilla was there to greet him.

Queen Sybilla died suddenly on the Island of the Women at ‘Loch Tay, the cell of the canons of Scone’ on 12 or 13 July 1122 and was buried at Dunfermline Abbey. Afterwards, the king granted the island on Loch Tay, and its surrounding lands, to the canons at Scone, to pray for the soul of Queen Sybilla, and himself. Alexander did not remarry after Sybilla’s death, leaving the crown to his brother, David, on his own death in 1124.

Queen Sybilla has left little imprint on history, beyond her name as a witness on a surviving charter and the founding of Scone Abbey. That she did not bear children, and therefore an heir for Alexander I, means that she did not have living descendants to keep her memory alive and memorialise her life and deeds, as Queen Margaret had. Her significance is, perhaps, not in her impact on Scotland but rather the physical link that she represented between the kingdoms and dynasties of England and Scotland, and thus demonstrating Scottish acceptance of Norman rule in England.

***

Notes:

1. Manuscript E, The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, edited and translated by Michael Swanton, p. 241; 2. John of Fordun’s Chronicle of the Scottish nation, pp. 217-218; 3. ‘filiam Henrici regis Anglorun ex concubine’ Orderic Vitalis cited in Danna Messer, Medieval Monarchs, Female Illegitimacy and Modern Genealogical Matters: Part 1: Sybilla, Queen of Scotland, c. 1090-1122, fmg.ac; 4. ‘Alexander…rex Scottorum filius regis Malcolmi et regine Margerete et…Sibilla regina Scottorum filia Henrici regis Anglie’ Scone, 1, p. 1. Quoted in fmg.ac/Projects/MedLands/SCOTLAND; 5. William of Malmesbury, 400, p. 349, quoted in fmg.ac/Projects/MedLands/SCOTLAND; 6. William of Malmesbury, quoted in Messer, Medieval Monarchs, Female Illegitimacy and Modern Genealogical Matters: Part 1: Sybilla, Queen of Scotland, c. 1090-1122

Images:

Courtesy of Wikipedia except Henry I which is ©2025 Sharon Bennett Connolly

Sources:

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, edited and translated by Michael Swanton; John of Fordun’s Chronicle of the Scottish nation; Danna Messer, Medieval Monarchs, Female Illegitimacy and Modern Genealogical Matters: Part 1: Sybilla, Queen of Scotland, c. 1090-1122; fmg.ac/Projects/MedLands/SCOTLAND; Jessica Nelson, Sybilla (d. 1122), queen of Scots and consort of Alexander I, Oxforddnb.com; Walter Bower, Scotichronicon; A.A.M. Duncan, Alexander I, Oxforddnb.com; Forester, The Chronicle of John Florence of Worcester with the two continuations; David Ross, Scotland, History of a Nation; Rosalind K. Marshall, Scottish Queens 1034-1714; Mike Ashley, A Brief History of British Kings & Queens; Richard Oram, editor, The Kings & Queens of Scotland

*

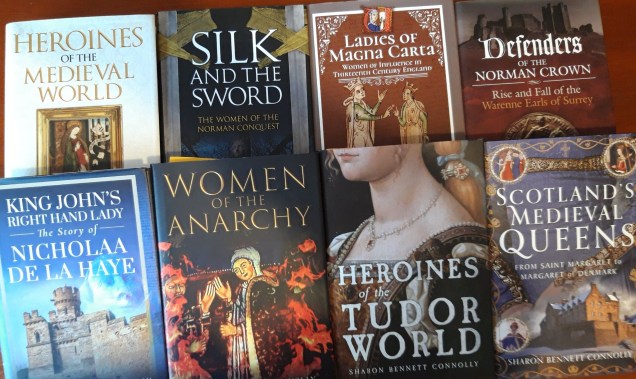

My books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online store.

Out now: Scotland’s Medieval Queens

Scotland’s history is dramatic, violent and bloody. Being England’s northern neighbour has never been easy. Scotland’s queens have had to deal with war, murder, imprisonment, political rivalries and open betrayal. They have loved and lost, raised kings and queens, ruled and died for Scotland. From St Margaret, who became one of the patron saints of Scotland, to Elizabeth de Burgh and the dramatic story of the Scottish Wars of Independence, to the love story and tragedy of Joan Beaufort, to Margaret of Denmark and the dawn of the Renaissance, Scotland’s Medieval Queens have seen it all. This is the story of Scotland through their eyes.

‘Scotland’s Medieval Queens gives a thorough grounding in the history of the women who ruled Scotland at the side of its kings, often in the shadows, but just as interesting in their lives beyond the spotlight. It’s not a subject that has been widely covered, and Sharon is a pioneer in bringing that information into accessible history.’ Elizabeth Chadwick (New York Times bestselling author)

Available now from Amazon and Pen and Sword Books

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. Heroines of the Tudor World is now available from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how Empress Matilda and Matilda of Boulogne, unable to wield a sword themselves, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It shows how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other. Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org. Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell and Michael Jecks, and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

Every episode is also now available on YouTube.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online store.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter, Threads, Bluesky and Instagram.

*

©2025 Sharon Bennett Connolly