The author of The King’s Mistress (U.S. title The September Queen) explores Tudor England with the tale of Bess of Hardwick—the formidable four-time widowed Tudor dynast who became one of the most powerful women in the history of England.

On her twelfth birthday, Bess of Hardwick receives the news that she is to be a waiting gentlewoman in the household of Lady Zouche. Armed with nothing but her razor-sharp wit and fetching looks, Bess is terrified of leaving home. But as her family has neither the money nor the connections to find her a good husband, she must go to facilitate her rise in society.

When Bess arrives at the glamorous court of King Henry VIII, she is thrust into a treacherous world of politics and intrigue, a world she must quickly learn to navigate. The gruesome fates of Henry’s wives convince Bess that marrying is a dangerous business. Even so, she finds the courage to wed not once, but four times. Bess outlives one husband, then another, securing her status as a woman of property. But it is when she is widowed a third time that she is left with a large fortune and even larger decisions—discovering that, for a woman of substance, the power and the possibilities are endless . . .

Venus in Winter by Gillian Bagwell transports you to Tudor England.

In her novel, Venus in Winter, Gillian Bagwell tells the story of the early years of one of my favourite Tudor heroines, Bess of Hardwick. Gillian follows Bess’s life from her teenage years through her first 3 marriages. The first, to Robert Barlow, which was over all-too-soon. Her second husband, William Cavendish, helped her claim her dower rights from Barlow’s estate and, through Cavendish leaving his estate to her, rather than their children, gave Bess the financial independence that few Tudor women knew and enjoyed. The third husband, Sir William St Loe, was trusted by Queen Elizabeth I herself. Each successive marriage gave Bess greater influence, position and financial independence.

Bess of Hardwick is a woman determined never to be poor again. Clever, beautiful and wise beyond her years, she makes the rules of Tudor society work for her.

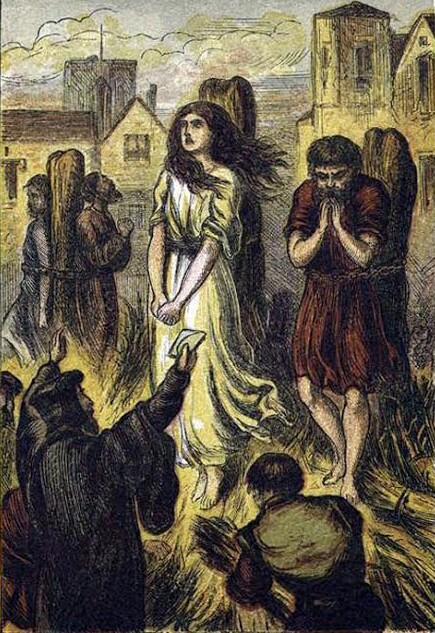

But it is not all about money. Gillian Bagwell’s Bess is a fine young woman, learning to find her way in the world, to trust her own instincts to help her children and her wider family. She suffers loss, hardship and uncertainty and is the stronger for it. But this is Tudor England! She also finds herself in the Tower of London, facing questions from the queen’s inquisitors. This is the portrayal of a remarkable young woman who became the matriarch of a powerful family.

On New Years’ Day, as the Zouches and their attendants made their way to the presence chamber of Hampton Court, Bess was very excited. For on this day the king would be presented with his gift – the splendid table and chess pieces, which had been completed in time and had traveled from London swaddled in layers of wool.

The mood at court was lighter and happier than at any time Bess could recall. Anne of Cleves was present, companionably chatting with King Henry, and the shadow of Catherine Howard was almost dispelled by the warmth and light from the hundreds of candles, which made the air redolent of honey. A band of musicians played jaunty dance tunes, and the walls were hung with garlands of holly and ivy. Near the king, a table was stacked with gifts of such magnificence that it staggered Bess. Golden goblets, engraved silver coffers, books in richly ornaments bindings, jeweled collars and belts, furs of deep and gleaming pile, which she longed to touch. But nothing like the chess table the Zouches had brought.

Rich pastries and savory morsels were piled on platters, and great bowls of punch perfumed the air with steam. The room rang with laughter and chatter. Bess, Lizzie, and Doll took up a position near the door where they could watch each new arrival while Audrey trailed Lady Zouche as she made her way around the room greeting friends.

“There’s Anne Basset,” Doll said. “I like her. She always makes me laugh.”

“Lady Latimer is looking very pretty, don’t you think?” Bess asked, eyeing the lady’s emerald silk gown with envy. She didn’t recognize the handsome dark-haired man next to her, but knew it was not Lord Latimer. “Her husband must be too ill to be here.”

“Small wonder, as old as he is,” Doll whispered. “That’s Sir Thomas Seymour with her.”

In Venus in Winter, Gillian Bagwell has skillfully recreated the Tudor world, from the wilds of Derbyshire, to the splendour of the Tudor court. From the last, fearful years of the reign of Henry VIII to the glory and pageantry of Elizabeth I. Her attention to detail and considerable research means that, while the story is fiction it is woven around the historical facts. From her descriptions of the Derbyshire countryside and the detail of the Tudor palaces, you know that Gillian took her research seriously and visited everything she could, adding a note of authenticity to the story.

The characters in Bess of Hardwick are deep and diverse. Bess of Hardwick is a complex young woman, spurred on by a childhood threatened by poverty. She is ambitious, not so much for success as for security. Some of the great names of the Tudor world also put in an appearance. From Elizabeth I to Robert Dudley to Katherine Grey, Bess’s world is occupied by the great and the good of the 16th century. Bess once served in the household of Frances Grey, daughter of Henry VIII’s sister and mother of Jane Grey and Gillian Bagwell draws their story into Bess’s, showing how deep Bess’s affection for the family went. And telling the story of the Nine Days’ Queen through her eyes.

Venus in Winter is not only a wonderful retelling of Bess of Hardwick’s story but also a fascinating exercise in observing the goings-on of the Tudor court through Bess’s eyes. The attention to detail is exquisite.

I would love to see Gillian write a sequel to this, tackling Bess’s last marriage to George Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury. It would be great to read her take on Bess and Shrewsbury’s deteriorating relationship as they act as gaolers for Mary Queens of Scots. And to see how Bess became friends with the captive queen, their scheming to marry Bess’s daughter to Mary’s cousin, that could have put Bess’s granddaughter, Arbella, on the throne, had it not all gone so terribly wrong. What a tale that would be! Especially with Gillian’s genius at storytelling.

To Buy the book: Venus in Winter is available from Amazon

About the author:

Gillian Bagwell’s historical novels have been praised for their vivid and lifelike characters and richly textured, compelling evocation of time and place. Her first career was in theatre, as an actress and later as a director and producer, and she founded the Pasadena Shakespeare Company and produced thirty-seven shows over ten years. Gillian has found her acting experience helpful to her writing, and many of the workshops and classes she’s taught at the annual Historical Novel Society Conferences in the US and the UK relate to her life in theatre, including writing effective historical dialogue, using acting tools to bring characters to life on the page, and giving effective public readings. She’s also a professional editor and provides writing coaching and manuscript evaluations. Gillian lives in Berkeley, California in the house where she grew up, her life enlivened by her five rescue cats.

*

My Books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

Out now: Scotland’s Medieval Queens

Scotland’s history is dramatic, violent and bloody. Being England’s northern neighbour has never been easy. Scotland’s queens have had to deal with war, murder, imprisonment, political rivalries and open betrayal. They have loved and lost, raised kings and queens, ruled and died for Scotland. From St Margaret, who became one of the patron saints of Scotland, to Elizabeth de Burgh and the dramatic story of the Scottish Wars of Independence, to the love story and tragedy of Joan Beaufort, to Margaret of Denmark and the dawn of the Renaissance, Scotland’s Medieval Queens have seen it all. This is the story of Scotland through their eyes.

‘Scotland’s Medieval Queens gives a thorough grounding in the history of the women who ruled Scotland at the side of its kings, often in the shadows, but just as interesting in their lives beyond the spotlight. It’s not a subject that has been widely covered, and Sharon is a pioneer in bringing that information into accessible history.’ Elizabeth Chadwick (New York Times bestselling author)

Available now from Amazon and Pen and Sword Books

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. Heroines of the Tudor World is now available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how Empress Matilda and Matilda of Boulogne, unable to wield a sword themselves, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It shows how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other. Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org. Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Elizabeth Chadwick, Helen Castor, Ian Mortimer, Scott Mariani and Bernard Cornwell and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

Every episode is also now available on YouTube.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter, Threads, Bluesky and Instagram.

*

©2025 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS