Little Lady Mary Seymour was the daughter of dowager Queen Kateryn Parr and her fourth, and final, husband, Thomas Seymour, Baron Seymour of Sudeley. Kateryn Parr was widowed for a third time with the death of Henry VIII in January 1547. By May of the same year, Queen Kateryn was married to the new king Edward VI’s uncle, Thomas Seymour, Lord High Admiral of England and Baron Seymour of Sudeley. This was said to be a love match and within months Kateryn found herself pregnant for what may have been the first time in her life. In the months before the birth, the queen had fitted out a nursery for her baby, decorated in Kateryn’s favourite colours of crimson and gold: the nursery had views of the gardens and the castle’s chapel. The queen’s joy was tempered by the scandal that had arisen from her husband’s attentions towards Kateryn’s stepdaughter, Elizabeth.

She wrote to Thomas Seymour of how active the unborn child was:

I gave your little knave your blessing, who like an honest man stirred apace after and before. For Mary Odell [one of her ladies] being abed with me had laid her hand upon my belly to feel it stir. It hath stirred these three days every morning and evening so that I trust when you come it will make you some pastime. And thus I end bidding my sweetheart and loving husband better to fare than myself.1

Kateryn gave birth to her only child, Mary, named after the dowager queen’s stepdaughter, Princess Mary, on 30 August 1548. At the age of 37, Kateryn was old to be having her first child, but both she and the baby had come through the labour safely and there doesn’t appear to have been any disappointment that the child was a girl rather than a boy.

Within just a few days of the birth, Kateryn was showing signs of puerperal fever, a bacterial complication of childbirth that was very dangerous in the centuries before antibiotics. As her condition worsened, Kateryn suffered bouts of delirium and moments of calm, when she appeared to rally. In her delirium, Kateryn railed against her husband, saying

‘I am not well handled, for those that be about me careth not for me but standith laughing at my grief and the more good I will to them, the less good they will to me.’2

Strongly denying her accusations, Seymour replied

‘Why, sweetheart, I would you no hurt.’3

Whether Kateryn truly believed Seymour wanted her dead, or was still smarting from how close he had got to the Princess Elizabeth, or the words, reported by Lady Tyrwitt, who was not a friend of Seymour’s, were misinterpreted, we will never know. Her pain, delirium and suspicion of her husband made Kateryn’s last days even more wretched.

Kateryn Parr died 6 days after little Mary’s birth, on 5 September 1548, at Sudeley Castle. She was laid to rest beneath the floor of St Mary’s Chapel in the castle grounds, with Lady Jane Grey acting as her chief mourner. Despite her fears that her husband had poisoned her, in her will, dictated as she was close to death, she left everything to Seymour, making him a very wealthy man.

Thomas Seymour was stunned by Kateryn’s death and grieved deeply. He abandoned Sudeley Castle and returned to London, seeking refuge at Syon House, the home of his brother, Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset and his wife. Little Lady Mary was placed in the care of his mother, Margery Seymour.

Mary was eventually taken into the care of Edward Seymour and his wife, Duchess Anne. Anne had herself given birth to a little boy shortly before Mary’s birth and had a house full of children, little Mary’s cousins. However, when her father was arrested for treason, having plotted to marry the Princess Elizabeth, and was being held in the Tower awaiting execution, he asked that his daughter should be given into the care of Katherine Willoughby (now Brandon), Duchess of Suffolk. Katherine had been a good friend of Kateryn Parr. She had herself been widowed in 1545 and was the mother of 2 teenage boys, Henry and Charles Brandon.

Mary could have been given into the care of Kateryn Parr’s brother, William Parr, Marquess of Northampton, but he had recently found himself out of favour with Edward Seymour, the Lord Protector, as he had tried to divorce his wife, Anne Bourchier, in order to marry Elisabeth Brooks, who had served Seymour’s sister Jane when she was queen. This remarriage was considered illegal and outrageous and so, with such a scandal attached to him, Parr was not a suitable guardian to his niece; not that he appears to have paid any attention to Mary, nor expressed any desire to play a part in her life. Neither did Kateryn’s sister, Anne Herbert, Countess of Pembroke, show any interest in taking care of her niece, despite her own children being close in age to Mary.

With Thomas Seymour’s execution on 20 March 1549, Lady Mary Seymour, at just short of 7 months old, was a dispossessed orphan. Three days before her father’s death, whilst she was still in the custody of her uncle at Syon House, Mary had been granted £500 a year by the Privy Council. The money was for ‘dyettes, wages and lyvereyes of the household of Mistres Mary Seymour for a yere and a half ended at the Feast of the annunciation of Our Lady next cummyng [25 March].’4 However, that income was not transferred to Katherine Willoughby when the baby was moved to her residence at Grimsthorpe Castle in Lincolnshire. This left the duchess short of funds. The daughter of a queen, though not royal, was expected to be maintained to a certain standard. The little orphan arrived at Grimsthorpe Castle with her own household; her full complement of staff included her governess, a nurse and two maids. And it was left to Katherine, Duchess of Suffolk, to pay their wages.

By 24 July 1549, Katherine was writing to William Cecil, a secretary in Edward Seymour’s household at the time, in the hope that he may assist her in recovering payment for her expenses. She wrote:

‘It is said that the best means of remedy to the sick is first plainly to confess and disclose the disease, wherefore, both for remedy and again for that my disease is so strong that it will not be hidden. … All the world knoweth … what a very beggar I am.’5

Katherine said that her finances were worsening for numerous reasons but,

‘amongst others … if you will understand, not least the queen’s child hath layen, and still doth lie at my house, with her company about her, wholly at my charges. I have written to my lady of Somerset at large, that there be some pension allotted unto her according to my lord grace’s promise. Now, good Cecil, help at a pinch all that you may help.’6

The duchess included a list of items that Duchess Anne had promised to send on, including the plate and other items that had been intended for Mary’s nursery at Sudeley Castle. The duchess also complained that the baby’s governess, ‘with the maid’s nurse and others, daily call for their wages, whose voices my ears can hardly bear, but my coffers much worse.’7

It is saddening to read how little affection is given to this child who was so wanted by her parents. That she went from being the centre of Kateryn Parr’s world to being an unwanted burden on the late queen’s good friend. It seems that Katherine Willoughby’s pleas did eventually have an effect. In January 1550, application was made to the House of Commons for the restitution of Lady Mary Seymour, ‘daughter of Thomas Seymour, knight, late Lord Seymour of Sudeley and late High Admiral of England, begotten of the body of Queen Katherine, late queen of England’.8

By this act, the little girl, now 16 months old, was permitted to inherit any remaining property that had not been returned to the crown by her father’s attainder. This did not particularly improve Mary’s situation, as most of the property she would be allowed to inherit had already passed into the hands of others. This Act of Parliament is the last mention we have of Lady Mary Seymour in the historical record. The grant was not renewed when it became due in September 1550 and Lady Mary never claimed any of the remaining portion of her father’s estate.

It seems likely that the little orphan had died at Grimsthorpe Castle before her second birthday, her burial place now unknown. There are traditions that she survived. One such has her raised by her governess, eventually marrying Sir Edward Bushell, while a family in Sussex also claims to be descended from her. While neither of these scenarios are impossible, there is no historical record to substantiate the claims.

That we cannot say for certain is one more sad note in the life of a little girl whose birth was met with such joy by both her parents, but whose short life was replete with tragedy. She was a little pawn in the machinations of her elders.

Images:

Courtesy of Wikipedia except Grimsthorpe Castle which is ©2024 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS

Notes:

1. Linda Porter, Katherine the Queen: The Remarkable Life of Katherine Parr, the Last Wife of Henry VIII, p. 318; 2. ibid, p. 322; 3. ibid, p. 323; 4. Rebecca Larson, ‘The Disappearance of Lady Mary Seymour’, tudorsdynasty.com; 5. Linda Porter, Katherine the Queen, p. 341; 6. ibid, pp. 341-342; 7. ibid, p. 342; 8. ibid

Sources:

Linda Porter, Katherine the Queen: The Remarkable Life of Katherine Parr, the Last Wife of Henry VIII; Rebecca Larson, ‘The Disappearance of Lady Mary Seymour’, tudorsdynasty.com; Don Matzat, Katherine Parr: Opportunist, Queen, Reformer; Amy Licence, The Sixteenth Century in 100 Women; Anne Crawford, editor, Letters of the Queens of England; Oxforddnb.com; Elizabeth Norton, Catherine Parr; Elizabeth Norton, The Lives of Tudor Women; Sarah Morris and Natalie Grueninger, In the Footsteps of the Six Wives of Henry VIII.

*

My Books:

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online store.

OUT NOW! Heroines of the Tudor World

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. These are the women who made a difference, who influenced countries, kings and the Reformation. In the era dominated by the Renaissance and Reformation, Heroines of the Tudor World examines the threats and challenges faced by the women of the era, and how they overcame them. From writers to regents, from nuns to queens, Heroines of the Tudor World shines the spotlight on the women helped to shape Early Modern Europe.

Heroines of the Tudor World is now available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK.

Coming 30 January 2025: Scotland’s Medieval Queens

Scotland’s history is dramatic, violent and bloody. Being England’s northern neighbour has never been easy. Scotland’s queens have had to deal with war, murder, imprisonment, political rivalries and open betrayal. They have loved and lost, raised kings and queens, ruled and died for Scotland. From St Margaret, who became one of the patron saints of Scotland, to Elizabeth de Burgh and the dramatic story of the Scottish Wars of Independence, to the love story and tragedy of Joan Beaufort, to Margaret of Denmark and the dawn of the Renaissance, Scotland’s Medieval Queens have seen it all. This is the story of Scotland through their eyes.

Available for pre-order now.

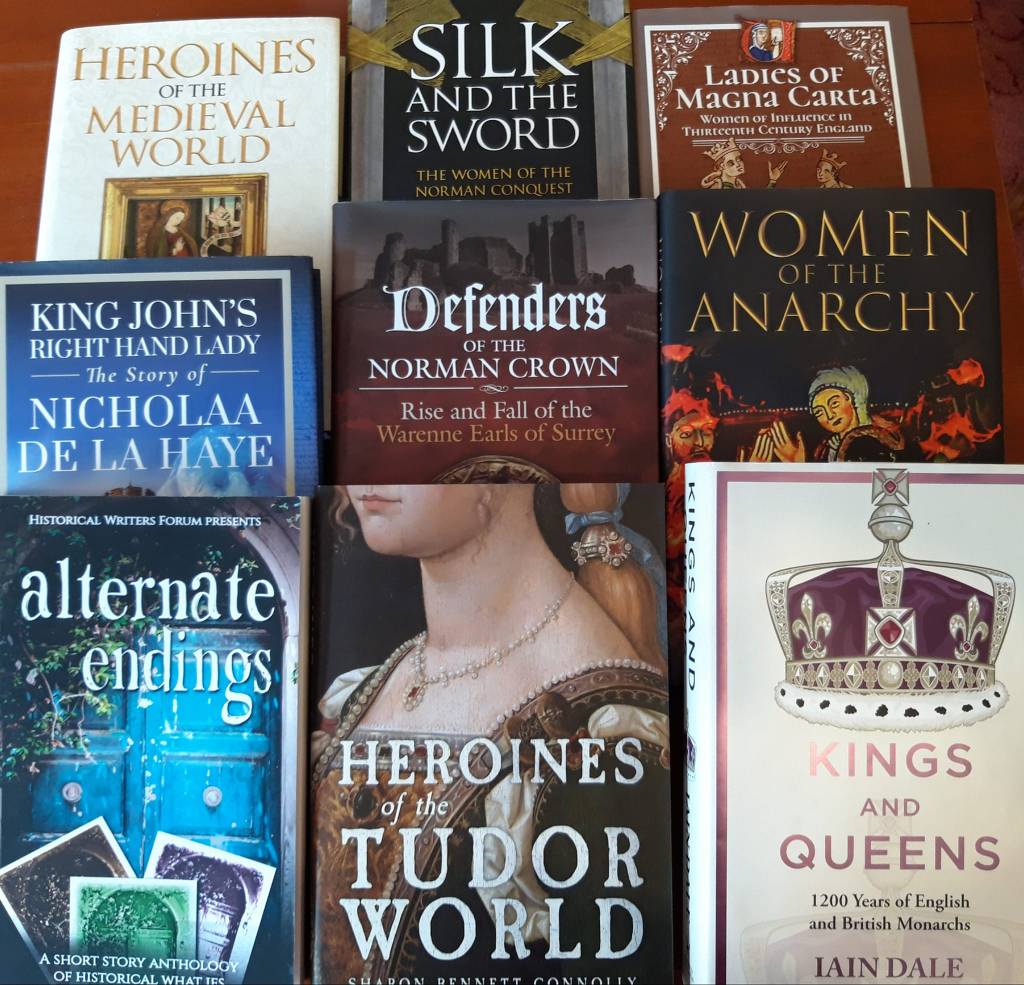

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how Empress Matilda and Matilda of Boulogne, unable to wield a sword themselves, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It shows how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other. Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon. Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org.

Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell, and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online store.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter, Threads and Instagram.

*

©2024 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS.