Constance of Castile was born in 1354 at Castro Kerez, Castile. Her father was Peter, or Pedro, king of Castile. Although he had earned himself the nickname of Peter the Cruel, he was also known as Peter the Just, depending on whether you were talking to his enemies, or his friends. In 1353 18-year-old Peter had married, in a secret ceremony, Maria de Padilla, who would bear him 4 children; of which Constance was the second oldest.

In the summer of the same year, a couple of months shy of his 19th birthday, on 3rd June, Peter had been practically coerced into marriage with 14-year-old Blanche de Bourbon, by his mother, Maria of Portugal, and his counsellors. Blanche was the daughter of Peter I, Duke of Bourbon, and Isabella de Valois; through her mother, Blanche was a cousin of the king of France. As a consequence of the marriage, Peter was forced to deny that a marriage ceremony with Maria ever took place. However, almost immediately after the wedding, Peter deserted his new bride and returned to Maria.

Blanche was imprisoned in the castle of Arevalo. Her cousin, Jean II, King of France, called for her release and asked the pope to excommunicate Peter for imprisoning her. The pope, Innocent VI, refused. Blanche was eventually moved to the town of Medina Sidonia, far remote from any possible rescue by Peter’s enemies from Aragon or France. It was at Medina Sidonia that Blanche died in 1361, though whether by murder or from natural causes is disputed (but that is a story for another time…).

Peter was married again, in 1354, to Juana de Castro, with whom he had a son, John. Despite the marriage, his relationship with Maria de Padilla endured. Peter and Maria were together until Maria’s death in 1361, probably from plague, and they had 3 daughters and a son. Although their son died young, their 3 daughters grew to adulthood. The eldest, Beatrice, entered the Abbey of Santa Clara at Tordesillas and so it would be Constance who eventually became her father’s heir.

Little is known of Constance’s childhood. She was around 7 when her mother died, her sister Isabella was a year younger and their baby brother, Alfonso was about 2. Alfonso would die in 1362.

Peter of Castile was engaged in constant wars with Aragon from 1356 to 1366, followed by the 1366 Castilian Civil War which saw him dethroned by his illegitimate half-brother, Henry of Trastamara.

Peter turned to his neighbours for help. He fled over the Pyrenees, to Aquitaine and England’s Prince of Wales, Edward the Black Prince. Peter brought his 2 daughters with him. The Black Prince agreed to mount an expedition to restore Peter to his throne, and would take his brother, John of Gaunt, along with him.

Constance and Isabella were handed over to the English as collateral against thee repayment of the costs of the expedition; a staggering £176,000 that Peter could never hope to repay.

In 1367 the Black Prince and John of Gaunt led an army across the Pyrenees, defeating Henry of Trastamara at the Battle of Najera, despite his being backed by the French. Trastamara fled Castile and Peter was restored to his throne, but could not repay the costs of the expedition. Unable to pay his army, and with his health in decline, the Black Prince left Spain for Aquitaine.

Peter was eventually murdered by Henry of Trastamara in March 1369; Henry usurped the throne as King Henry II, ignoring the rights of his niece Constance, who became ‘de jure’ Queen of Castile on 13th March 1369. However, Constance and her sister remained in English hands.

John of Gaunt’s wife of almost 10 years, Blanche Duchess of Lancaster, had died at Tutbury on 12th September, 1368, more likely from the complications of childbirth than from the plague. Shortly after John started a liaison with a woman who would be his mistress for the next 25 years, Katherine Swynford.

However, John of Gaunt was not done with his dynastic ambitions and saw in Constance of Castile the chance to gain his own crown. John and Constance were married, probably at Rocquefort, in Guyenne on 21st September 1371.

From 1372 John assumed the title King of Castile and Leon, by right of his wife. Crowds lined the streets when, as Queen of Castile, Constance was given a ceremonial entry into London in February 1372. Her brother-in-law, the Black Prince, escorted her through the city to be formally welcomed by her husband at his residence of the Savoy Palace.

Constance’s sister, Isabella, came with her, and would marry Constance’s brother-in-law Edmund of Langley, 5th son of Edward III, in July 1372.

Little is known of Constance’s relationship with her husband’s mistress, Katherine Swynford; except for an incident in June 1381. Amid the turmoil of the Peasant’s Revolt, John is said to have given up his mistress and reconciled with his wife, suggesting their relationship wasn’t all smooth. Katherine returned to her manor in Lincolnshire where, it seems, John visited her from time to time.

Constance was made a Lady of the Garter in 1378. Constance and John, King and Queen of Castile and Duke and Duchess of Lancaster, had 2 children. A son, John, was born in 1374 at Ghent in Flanders, but died the following year. Their daughter Catherine, or Catalina, of Lancaster was born at Hertford Castle, sometime between June 1372 and March 1373. She would be made a Lady of the Garter in 1384.

John had several plans to recover his wife’s Castilian crown, but suffered from a lack of finances. Until 1386 when John I of Castile, son of Henry of Trastamara, attempted to claim the crown of Portugal. John of Avis, King of Portugal, turned to John of Gaunt for help. John saw this as his opportunity to overthrow John of Castile and claim the crown.

Having landed in Galicia, however, John was unable to bring the Castilians to battle and his army succumbed to sickness. The opposing forces eventually agreed the Treaty of Bayonne, where in return for a substantial sum, John of Gaunt abandoned his claim to Castile. The treaty also saw a marriage alliance, between John of Castile’s son, Henry and Constance and John’s daughter, Catherine.

Catherine married Henry III of Castile in September 1388 at the Church if St Antolin, Fuentarrabia, Castile. Catherine therefore sat on the throne denied her mother. Catherine would have 3 children; 2 daughters, Katherine and Mary, and a son. Catherine and Henry’s son, John II, would succeed his father just a few months after his birth, with Catherine having some limited say in the Regency, and custody of her son until he was around 10. She died on the 2nd June 1418 and is buried in Toledo, Spain. Her great-granddaughter, Catherine of Aragon, would marry Henry VIII of England.

Constance and John returned to England in 1389. Constance of Castile died on the 24th March 1394 at Leicester Castle and was buried at Newark Abbey in Leicester, far away from her Castilian homeland. Just two years later her widower would marry his long-time mistress, Katherine Swynford. When he died in 1399, however, John of Gaunt chose to be buried beside his first wife, Blanche of Lancaster.

It is hard to imagine that Constance was happy with her husband’s living arrangements, a belief highlighted by the 1381 reconciliation. It cannot have been easy, being at the centre of a love story that was not her own. John of Gaunt had offered Constance the chance to be a part of the English royal family, and to recover her crown. Although he failed in his personal ambition, John of Gaunt did manage to secure the crown for Constance’s descendants, through their daughter Catherine and grandson, John II of Castile.

*

Pictures taken from Wikipedia.

*

Sources: The Perfect King, the Life of Edward III by Ian Mortimer; The Life and Time of Edward III by Paul Johnson; The Reign of Edward III by WM Ormrod; The Mammoth Book of British kings & Queens by Mike Ashley; Britain’s’ Royal Families, the Complete Genealogy by Alison Weir; Brewer’s British Royalty by David Williamson; The Plantagenets, the Kings Who Made Britain by Dan Jones; englishmonarchs.co.uk; The Oxford Companion to British History edited by John Cannon; Chronicles of the Age of Chivalry Edited by Elizabeth Hallam.

*

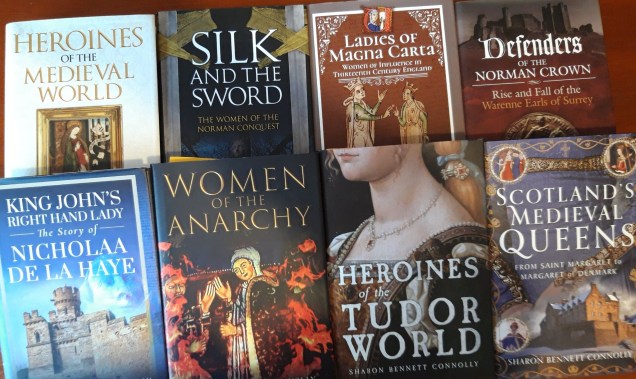

My Books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online store.

Out now: Scotland’s Medieval Queens

Scotland’s history is dramatic, violent and bloody. Being England’s northern neighbour has never been easy. Scotland’s queens have had to deal with war, murder, imprisonment, political rivalries and open betrayal. They have loved and lost, raised kings and queens, ruled and died for Scotland. From St Margaret, who became one of the patron saints of Scotland, to Elizabeth de Burgh and the dramatic story of the Scottish Wars of Independence, to the love story and tragedy of Joan Beaufort, to Margaret of Denmark and the dawn of the Renaissance, Scotland’s Medieval Queens have seen it all. This is the story of Scotland through their eyes.

Available now from Amazon and Pen and Sword Books

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. Heroines of the Tudor World is now available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how Empress Matilda and Matilda of Boulogne, unable to wield a sword themselves, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It shows how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other. Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org. Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell and Michael Jecks, and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved. Every episode is also now available on YouTube.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online store.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter, Threads, Bluesky and Instagram.

*

©2015 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS