22 August is a famous date in history. The Battle of Bosworth, on 22 August 1485 is often seen as the end of one era and the beginning of another: the end of the medieval age and the beginning of the early modern. It was the end of the royal line of the Plantagenets, begun under Henry II in 1154 and ended with the death of Richard III on that fateful August day. It was the advent of, arguably, the most famous royal house in history: the house of Tudor, which ruled England from 1485 to 1603.

But Bosworth was not the only battle fought on English soil on 22 August. 347 years before, during the period known to history as the Anarchy, when King Stephen stole the English throne from his cousin Empress Matilda. At Northallerton in North Yorkshire, an English army faced a Scots army in what would come to be known as the Battle of the Standard; between the forces of King Stephen and those of his wife’s uncle – and also the uncle of Empress Matilda – David I, King of Scots.

On his marriage to Matilda de Senlis, arranged by his brother-in-law King Henry, David acquired lands in Northampton, Bedford, Cambridge and Huntingdon, as well as lands stretching from South Yorkshire to Middlesbrough, which would become known as the ‘honour of Huntingdon’. By the first Treaty of Durham, agreed in February 1136, at which David had refused to do homage to Stephen but allowed his son to do so, young Henry was given Doncaster and the lordship of Carlisle. He also received his mother’s inheritance, the honour and earldom of Huntingdon, paying homage for these lands to King Stephen at York. At Stephen’s Easter court that same year, Henry sat at the king’s right hand, his royal birth giving him precedence ahead of the English earls. This infuriated Earl Ranulf of Chester, who had wanted Carlisle for himself, and Simon (II) de Senlis, Henry’s older half-brother, who maintained a rival claim to the Huntingdon lands.

The two barons withdrew from the court in disgust. As the grandson of Earl Waltheof, Henry also demanded the earldom of Northumberland. When Stephen refused to relinquish it, Scottish raids into Northumberland were renewed. David was ostensibly arguing that he was supporting his niece, Empress Matilda, in her struggle with Stephen over the English crown, though his actual motives were far from selfless. The Gesta Stephani was generous in assessing the Scots king’s dilemma:

In Scotland, which borders on England, with a river fixing the boundary between the two kingdoms, there was a king of a gentle heart, born of religious parents and equal to them in his just way of living. Since he had in the presence of King Henry, together with the other magnates of the kingdom, or rather first of all of them, bound himself with an oath that on King Henry’s death he would recognise no-one as his successor except his daughter or her heir, he was greatly vexed that Stephen had come to take the tiller of the kingdom of the English. But because it had been planned and carried out by the barons themselves without consulting him he wisely pondered the ultimate result and waited quietly for some time to see what end the enterprise would come.1

In the early months of 1138, David had exploited Stephen’s preoccupation with the siege of Bedford Castle to lead a foray into Northumberland. The Scots king was apparently spurred on by a letter from Empress Matilda ‘stating that she had been disinherited and deprived of the kingdom promised to her on oath, that the laws had been made of no account, justice trampled under foot, the fealty of the barons of England and the compact to which they had sworn broken and utterly disregarded, and therefore she humbly and mournfully besought him to aid her as a relation, since she was abandoned, and assist her as one bound to her by oath, since she was in distress’.2

Whether acting in response to his niece’s pleas or to pursue his own interests, David had moved south in January 1138. He had besieged Wark Castle and led a chevauchée further south. However, he had retreated into the Scottish borders when Stephen brought a substantial force against him. From Roxburgh, David awaited the departure of the English army before renewing his campaign. The Scots ventured across the border, once again, on 8 April, this time targeting the coastal regions of Northumberland and County Durham in a campaign of plunder and waste. Stephen was now tied up in the south in campaigns against various rebel barons, including William Fitz Alan, who was married to a niece of Robert, Earl of Gloucester, and Arnulf of Hesdin, who held Shrewsbury Castle against the king.

Robert of Gloucester, Empress Matilda’s illegitimate half-brother, had finally made a move in favour of his sister, issuing Stephen with a diffidatio, a chivalric device which was a formal statement of renunciation of allegiance and homage. According to William of Malmesbury, Robert ‘sent representatives and abandoned friendship and faith with the king in the traditional way, also renouncing homage, giving as the reason that his action was just, because the king had both unlawfully claimed the throne and disregarded, not to say betrayed, all the faith he had sworn to him’.3

David took advantage of these distractions and again crossed the River Tees with a Scottish army in July. He sent two Scottish barons to lay siege to Wark Castle while he headed further south. Eustace fitz John, deprived of Bamburgh Castle by King Stephen but still in control of Alnwick, chose to add his own forces to those of King David. The army marched past Bamburgh until the garrison, believing themselves impregnable, taunted the Scots from the safety of the castle’s formidable walls. The Scots promptly attacked, breaking down the barricades and killing everyone in the castle. Bernard de Baliol was then sent north by King Stephen and he and Robert de Bruce were tasked with discussing terms with the Scots. The proposal was that if the Scots went home, Prince Henry would be given the earldom of Northumberland. David rejected the offer.

Stephen, it seems, was beset on all sides, with invaders on his northern borders, rebellion within his kingdom and trouble across the Channel in Normandy. He employed all his senior commanders in putting out the fires – including his wife, Queen Matilda. In the late summer of 1138, following the capitulation of Shrewsbury, Stephen had hanged that town’s entire garrison, learning from his leniency at Exeter. He then ‘besieged Dover with a strong force on the landward side, and sent word to [Queen Matilda’s] friends and kinsmen and dependents in Boulogne to blockade the force by sea. The people of Boulogne proved obedient, gladly carried out their lady’s commands and, with a great fleet of ships, closed the narrow strait to prevent the garrison receiving any supplies.’4 This military pressure, combined with the persuasive power of Robert de Ferrers, father-in-law of the rebel garrison’s commander, Walchelin Maminot, caused Walchelin to surrender to the queen, in late August or early September. The retribution meted out to the Shrewsbury garrison was probably another persuasive argument to the recalcitrant defenders.

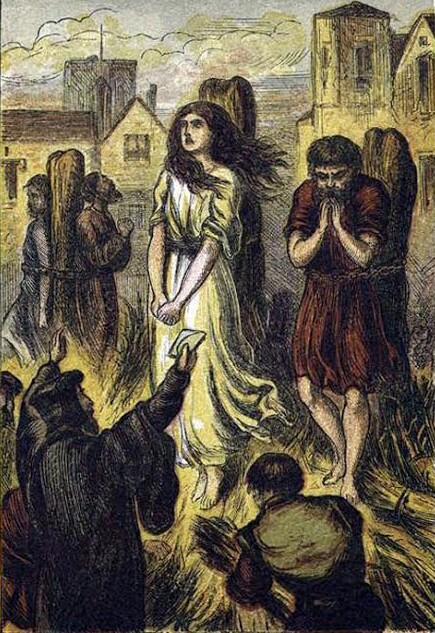

David had overplayed his hand by allowing his troops from Galloway to plunder the countryside, thus uniting the northern barons in their determination to put an end to these all-too-frequent Scottish forays into England. With Stephen, his loyal generals and his wife occupied with rebels in the south of England, the defence of the north fell to Thurstan, Archbishop of York since 1115 and nearing his seventieth year. Placing the archbishop in command was a move which would prevent baronial squabbling over seniority. Thurstan called for a crusade against the Scots and mustered his army at York. The Scots refused all offers of negotiations, so the archbishop marched his force to Northallerton in Yorkshire, just 30 miles north-west of York. Calling upon holy favour, the army was preceded by the banners of St Peter, St John of Beverly and St Wilfrid of Ripon, flying on a mast which itself was mounted on a carriage.

On 22 August 1138, with the carriage supporting the standards placed on the summit of the southernmost of two hillocks next to the Darlington road, the troops were arrayed to the front of their standards. Above the emblems of the saints a banner read, ‘Body of the Lord, to be their standard-bearer and the leader of their battle.’5 It is from this pious display that the ensuing clash, the Battle of the Standard, would get its name. The English forces were formed in three groups, with dismounted men-at-arms in the front rank, a body of knights around the standards and the shire levies deployed at the rear and on both flanks. The Scots were drawn up on the northern hillock, with men-at-arms and archers in the front and the poorly equipped men from Galloway and the Highlanders in the rear. The unarmoured men from Galloway complained bitterly about being placed in the rear and demanded the rightful place of honour in the front of the battleline, to the extent that King David, against his better judgement, granted them their wish to spearhead the attack. Prince Henry took command of the right flank, comprising the troops from Strathclyde and the eastern Lowlands and a body of mounted knights. The left was formed of men from the western Highlands. The king led the small reserve, made up of the men from Moray and the eastern Highlands.

The presence of the apostle and two Yorkshire saints in their force, arrayed against a foe containing a contingent of Picts, led to a sense among the English that they were on a noble crusade. According to Henry of Huntingdon, the Bishop of Durham then gave a stirring speech before the bishops and priests retreated from the field:

… Rouse yourselves, then, gallant soldiers, and bear down on an accursed enemy with the courage of your race and in the presence of God. Let not their impetuosity shake you, since the many tokens of our valour do not deter them. They do not cover themselves with armour in war; you are in the constant practice of arms in time of peace, that you may be at no loss in the chances at the day of battle. Your head is covered with the helmet, your breast with a coat of mail, your legs with greaves and your whole body with shield. Where can the enemy strike you when he finds you sheathed in steel … It is not so much the multitude of a host, as the valour of a few which is decisive. Numbers, without discipline, are a hindrance to success in the attack and to retreat in defeat. Your ancestors were often victorious when they were but a few against many…6

As the English soldiers shouted out ‘Amen! Amen!’ in response to the bishop’s speech, the Scottish army advanced with their own battle cry of ‘Alban! Alban!’ on their lips. The men of Galloway launched the initial attack and ‘bore down on the English mailed knights with a cloud of darts and their long spears’.7 The unclothed Galwegians had no protection against the hail of arrows and English swords, though their sheer ferocity saw them temporarily breach the English front rank. Even so, they could get no further: ‘The whole army of English and Normans stood fast around the Standard in one solid body.’8 It was a stalemate that Prince Henry attempted to break by leading a mounted charge against the English forces. Although he sustained heavy losses, the prince broke through the English ranks and continued towards the enemy’s rear, reaching the horse lines. The English closed ranks before the Scots foot soldiers could take advantage of the gap created by the prince’s charge.

Henry of Huntingdon reserves praise for the prince: ‘[David’s] brave son, heedless of what his countrymen were doing, and inspired only by his ardour for the fight and for glory, made a fierce attack, with the remnant of the fugitives on the enemy’s ranks … But this body of cavalry could by no means make any impression against men sheathed in armour, and fighting on foot in a close column; so that they were compelled to retire with wounded horses and shattered lances, after a brilliant but unsuccessful attack.’9 Finding himself marooned behind enemy lines, the prince ordered his men to discard any identifying badges and mingle with the English forces until they could escape. The ruse worked and the prince was able to make his way back to Carlisle.

According to Huntingdon, the men of Galloway were put to flight when their chief fell, pierced by an arrow. Fighting along the line, and having seen what befell the Galwegians, the remainder of the Scots army began to falter. Seeing that the battle was lost, men began to flee. It began as a trickle, but soon the greater part of the army was in retreat. King David had chosen the greatest of the Scottish knights as his personal guard, and they remained steadfast almost to the last. Once they saw the battle was lost, they persuaded the king to call for his horse and retreat rather than risk death or capture. Henry of Huntingdon reports 11,000 Scottish dead against few English casualties, with Gilbert de Lacy’s brother the only English knight to fall on the field of battle.

The English, however, failed to pursue the fleeing Scots. David was therefore able to march his surviving army north to join the forces that had been besieging Wark Castle since June. Satisfied that they had seen off the Scottish threat, the English had withdrawn, leaving only a small contingent in the field to reduce Eustace fitz John’s castle at Malton. Negotiations for peace could then begin:

After the war between the two kings had lasted for a long time, created terrible disorder, and brought widespread calamity, a peace mission was sent out by God’s will; travelling to and fro between the two kings, who were exhausted by the slaughter, destruction, ceaseless anxieties, and hardships, the envoys succeeded in restoring harmony between them.10

A truce was arranged at Carlisle at the end of September 1138 and negotiations for a lasting peace began in earnest. On 9 April 1139, the Treaty of Durham was concluded between King Stephen and David of Scotland. As part of the treaty, Henry of Scotland would marry Ada de Warenne, daughter of William de Warenne, 2nd Earl of Warenne and Surrey. Not that peace would prevent King David from continuing to aid his niece, Empress Matilda, in her struggles against King Stephen, but that is another story.

Notes:

1. K. R. Potter (trans.), Gesta Stephani; 2. ibid; 3. William of Malmesbury quoted in Matthew Lewis, Stephen and Matilda’s Civil War: Cousins of Anarchy; 4. John of Worcester quoted in Patricia A. Dark, The Career of Matilda of Boulogne as Countess and Queen in England, 1135-1152; 5. Matthew Lewis, Stephen and Matilda’s Civil War; 6. Thomas Forester (trans. and ed.), The Chronicle of Henry of Huntingdon. Comprising the history of England, from the invasion of Julius Caesar to the accession of Henry II. Also,the Acts of Stephen, King of England and Duke of Normandy; 7. ibid; 8. ibid; 9. ibid; 10. Ordericus Vitalis, The Ecclesiastical History of Orderic Vitalis, 1075-1143, book XIII.

Images:

King David, King Stephen, Empress Matilda and the coin of Prince Henry of Scotland are courtesy of Wikipedia. All photos are ©2024 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS

Sources:

Potter, K. R. (trans.), Gesta Stephani; Matthew Lewis, Stephen and Matilda’s Civil War: Cousins of Anarchy; Patricia A. Dark, The Career of Matilda of Boulogne as Countess and Queen in England, 1135-1152; Thomas Forester (trans. and ed.), The Chronicle of Henry of Huntingdon. Comprising the history of England, from the invasion of Julius Caesar to the accession of Henry II. Also, the Acts of Stephen, King of England and Duke of Normandy; David Smurthwaite, The Complete Guide to the Battlefields of Britain; David Crouch, The Reign of King Stephen; Keith Stringer, ‘Henry, Earl of Northumberland (c. 1115-1152)’, Oxforddnb.com; G.W.S. Barrow, ‘David I (c. 1185-1153)’, Oxforddnb.com; Keith Stringer, ‘Ada [née Ada de Warenne], countess of Northumberland (c. 1123-1178)’, Oxforddnb.com; Victoria Chandler, ‘Ada de Warenne, Queen Mother of Scotland (c. 1123-1178)’, The Scottish Historical Review, Vol. 60, no. 170; Farrer, W. and C. T. Clay (eds), Early Yorkshire Charters, Volume 8: The Honour of Warenne; Henry of Huntingdon, The History of the English People 1000–1154; Catherine Hanley, Matilda: Empress, Queen, Warrior; Marjorie Chibnall, The Empress Matilda: Queen Consort, Queen Mother and Lady of the English; Edmund King, King Stephen.

*

My Books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online store.

Out now: Scotland’s Medieval Queens

Scotland’s history is dramatic, violent and bloody. Being England’s northern neighbour has never been easy. Scotland’s queens have had to deal with war, murder, imprisonment, political rivalries and open betrayal. They have loved and lost, raised kings and queens, ruled and died for Scotland. From St Margaret, who became one of the patron saints of Scotland, to Elizabeth de Burgh and the dramatic story of the Scottish Wars of Independence, to the love story and tragedy of Joan Beaufort, to Margaret of Denmark and the dawn of the Renaissance, Scotland’s Medieval Queens have seen it all. This is the story of Scotland through their eyes.

‘Scotland’s Medieval Queens gives a thorough grounding in the history of the women who ruled Scotland at the side of its kings, often in the shadows, but just as interesting in their lives beyond the spotlight. It’s not a subject that has been widely covered, and Sharon is a pioneer in bringing that information into accessible history.’ Elizabeth Chadwick (New York Times bestselling author)

Available now from Amazon and Pen and Sword Books

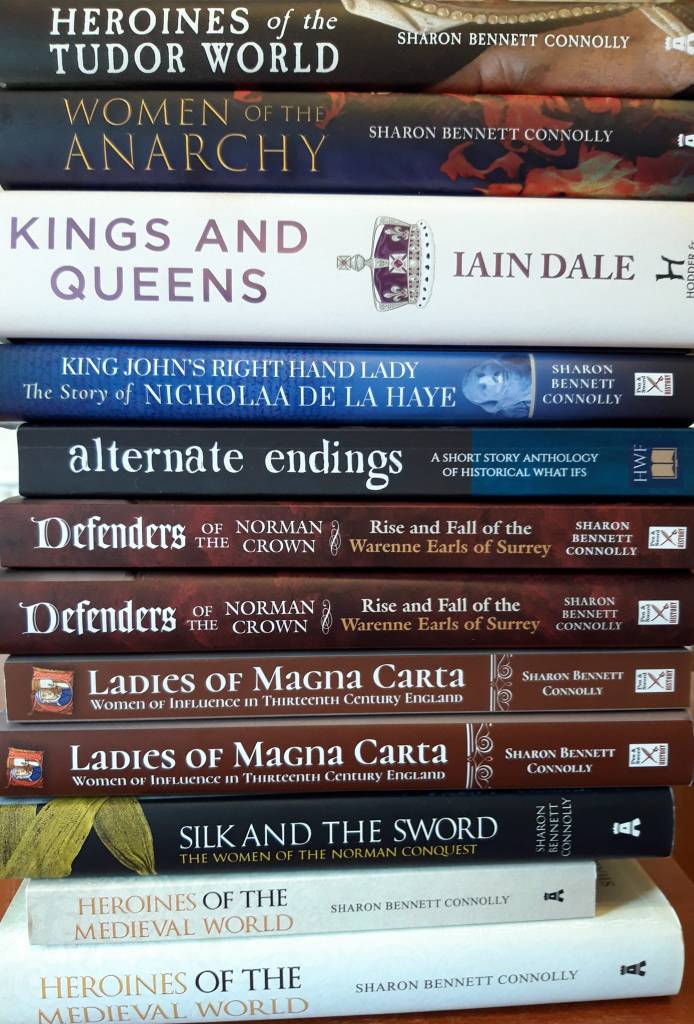

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

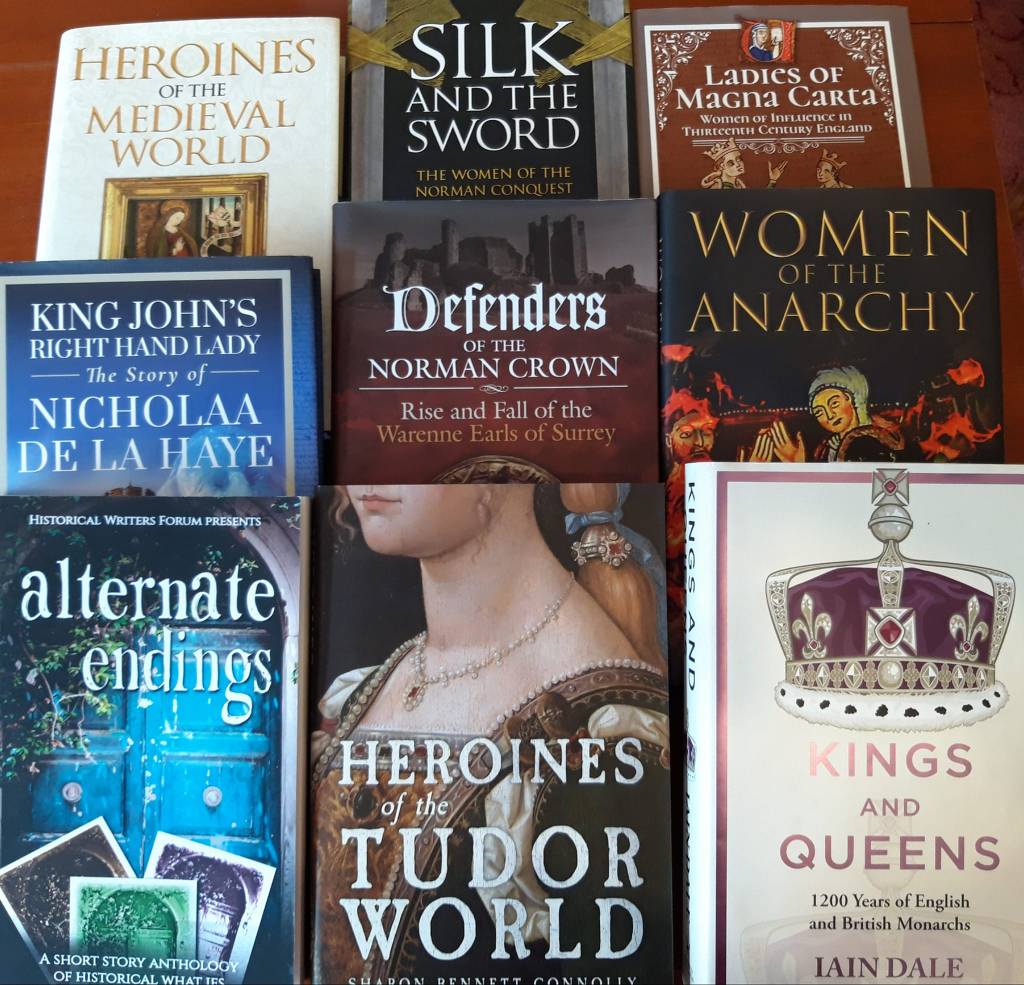

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. Heroines of the Tudor World is now available from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how Empress Matilda and Matilda of Boulogne, unable to wield a sword themselves, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It shows how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other. Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org. Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved. There are now over 70 episodes to listen to!

Every episode is also now available on YouTube.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter, Threads, LinkedIn, Bluesky and Instagram.

©2024 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS