It is a pleasure to welcome Jo Willett back to History…the Interesting Bits with a guest post about the subject of her latest book, the Georgian actress Sarah Siddons:

The famous actress Sarah Siddons, the Muse of Tragedy and the Queen of Drury Lane as she was known, was an expert on what we would today call brand control. The characters she played on stage were almost without exception highly moral, upstanding and noble. So, it was important that Sarah’s fans were encouraged to see her in the same light. In an age where many of her contemporary actresses on the London stage were either former sex workers or the mistresses of wealthy men (or both) Sarah ensured that every opportunity was taken to project the message that she was, by contrast, a happily married woman and a devoted mother.

Sarah had met her husband-to-be, William Siddons, when he joined her parents’ travelling acting troupe. She was aged 11 and he was 23. Biographers have tended to gloss over how quickly it was before the two started having romantic feelings for each other, for obvious reasons, but her parents soon became aware that the two were in love. They were wary of the relationship, not because of the age difference – Sarah’s father was similarly several years older than her mother and they had also met when her mother was young – but because they could see that William was not a particularly good actor. The story of how Sarah’s parents attempted to separate the lovers bears all the hallmarks of having been romanticised by Sarah in later life. But whatever happened, Sarah’s parents eventually decided to give their reluctant consent, and Sarah and William Siddons were married in Coventry in November 1773, when Sarah was 18 years old. The Siddons would always affectionately refer to each other as Sal and Sid.

So, Sarah was a married woman by the time she acquired fame and fortune as the greatest tragic actress of her generation. She had a false start at Drury Lane in David Garrick’s final season, but then rebuilt her career and returned to appear on stage at Drury Lane again, this time with Richard Brinsley Sheridan as manager, in 1782. Her first night was said to be one of the greatest ever seen on the British stage and she continued for some thirty years as the highest paid performer of her generation, mobbed by fans wherever she went. By 1782 she was already the mother of four children.

Sarah’s success enabled William to give up acting and to become her manager. In this role he proved himself often to be over-zealous in his demands for the fees he asked for her. The more Sarah earned in performance fees as the star, particularly in the regional theatres she toured every summer, the less was available to pay other actors in the company. Inevitably resentments festered. This was made worse when it appeared as if William had got Sarah out of appearing in ‘benefit’ performances, where the night’s takings went to a deserving actor in the cast. Her reputation suffered as a result, and she earned herself the nickname Lady Sarah Save-All.

Even though Sarah was the sole breadwinner, everything she earned was legally in William’s name. There is no evidence she questioned this – it was just how things were at the time. But William was not always wise when it came to investing. One year, for instance, he lost nearly a third of Sarah’s annual earnings, speculating on a new building at Saddlers Wells. Sarah never complained but she did find herself increasingly exhausted by her punishing work schedule and her health certainly suffered as a result.

It must also have been difficult for William that Sarah had such star status, whilst he was relatively unknown. She became the darling of King George III and his wife Queen Charlotte, for instance, but no mention was ever made of William’s having been introduced to the king and queen. It was as if he didn’t exist. Perhaps inevitably, William began to seek solace elsewhere. A friend called at the Siddons’ house one day to find Sarah weeping as she burned some papers which had alerted her to the fact her husband now had a mistress.

In 1792, ten years after Sarah’s triumph at Drury Lane, Hester Piozzi, a friend of Sarah’s, wrote in a letter to a mutual friend that the famous actress’s recent bout of ill-health could be put down to the fact that William had given his wife a Sexually Transmitted Infection, probably syphilis. This was far from being an uncommon problem at the time, but without the wonders of modern medicine it was incurable. Despite this, the couple clearly patched things up between the two of them, as their final child, a daughter named Cecilia, was born the following year.

Sarah never seems to have mentioned her STI. The only hint at it remains to this day Hester Piozzi’s letter. She would have dreaded any news of it escaping into the public domain. Her reputation as a happily married woman, the essence of respectability, would have been dangerously undermined. She was attended by the Royal Physician, Sir Lucas Pepys, who advised her to spend time recuperating at a spa. From then on she often suffered from what her public were told was erisypelas, a condition of the skin. In my biography I suggest that this was a means of covering up the fact her syphilis was developing.

But this was not the only problematic area in the Siddons’ relationship. Their two eldest daughters both suffered from increasingly serious diseases of the lungs, from which both of them were to die, Maria in 1798 and Sally in 1803. Sarah was able to rush to Maria’s bedside to be with her daughter for her last few weeks of life. But when Sally began to sicken during what would prove to be her last few months, her mother was on a long tour of Ireland. William wrote to his wife assuring her that Sally was recovering. He urged her to extend her tour from Dublin to Cork, specifically because there were bills to be met at home. Family life in London was proving to be particularly expensive at the time. Inevitably, and tragically, Sally worsened and died before her mother could make it back to be at her bedside for her end.

Sarah was always exceptionally guarded in her personal correspondence about her feelings towards her husband, but she let her mask slip around this time. ‘I have suffered too much from a husband’s unkindness,’ she wrote, ‘not to detest the man who treats a creature ill that depends on her husband for all her comforts.’ Clearly she blamed William for what had happened.

But Sarah herself was not entirely blameless. During her tour of Ireland she had met a young Spanish fencing master, Philomen Galindo. At first she could persuade herself that she was equally fond of Philomen and of his wife Catherine. But as the relationship developed, Catherine began to feel increasingly excluded and paranoid. Infatuated with Philomen, Sarah did her best to procure acting jobs for the couple in the new company of actors Sarah’s brother, the actor/manager John Philip Kemble, was putting together at Covent Garden. But John Philip made it very clear immediately that the Galindos were not the sort of people his celebrated sister should be associating with. It is impossible to prove whether Sarah was having a sexual relationship with Philomen Galindo, but his wife clearly thought she was. And when, several years later, Catherine had a pamphlet published, arguing her case and making public her side of the story, Sarah declined to sue for libel.

How much William knew about this is again hard to know, but it was just a year after their daughter Sally’s death, and just as Sarah had encouraged the Galindos to come to London on the false promise of finding jobs for them, that William and Sarah Siddons finally decided to separate. Very little adverse comment appeared in the press about this. All Sarah’s biographers up until now have played the separation right down and praised the actress for the dignity with which she handled the end of her marriage. One who was writing during Sarah’s lifetime wrote that William ‘retained at all times the sincerest regard for his incomparable lady.’ But the truth remained that the Siddons could no longer live with each other.

William drew up his will at the same time. He had asked Sarah to tell him what she would like from it. But, as she herself put it: ‘I can expect nothing more than you yourself have designed’. Despite all her worldly success, her reputation as the greatest tragic actress of her generation, and her image as someone as morally upright as the tragic heroines she played each night on stage, in real life her future was just as in jeopardy as theirs, dependent for her security on the goodwill of the husband from whom she was parting.

About the book:

Sarah Siddons grew up as a member of a family troupe of travelling actors, always poor and often hungry, resorting to foraging for turnips to eat. But before she was 30 she had become a superstar, her fees greater than any actor – male or female – had previously achieved. Her rise was not easy. Her London debut, aged just 20, was a disaster and could have condemned her to poverty and anonymity. But the young actress – already a mother of two – rebuilt her career, returning triumphantly to the capital after years of remorseless provincial touring. She became Britain’s greatest tragic actress, electrifying audiences with her performances. Her shows were sell-outs. Adored by theatre audiences, writers, artists and the royal family alike, Sarah grasped the importance of her image. She made sure that every leading portrait painter captured her likeness, so that engravings could be sold to her adoring public. In an eighteenth-century world of vicious satire and gossip, she also battled to manage her reputation. Married young, she took constant pains to portray herself as a respectable and happily married woman, even though her marriage did not live up to this ideal. Sarah’s story is not just about rags to riches; this remarkable woman also redefined the world of theatre and became the first celebrity actress.

Sarah Siddons: The First Celebrity Actress is available from Amazon

About the author:

Jo Willett has been an award-winning TV drama and comedy producer all her working life. Her credits range from the recent Manhunt, starring Martin Clunes, to Birds of a Feather. Her most relevant productions include Brief Encounters (a fictionalised story of the first women who ran Ann Summers parties in the 1980s), The Making of a Lady (an adaption of the Frances Hodgson Burnett novel _The Making of a Marchioness_), Bertie and Elizabeth (telling the story of the Queen Mother’s marriage) and the BAFTA-and-RTS Award-Winning A Rather English Marriage (starring Albert Finney, Tom Courtenay and Joanna Lumley, adapted from the novel of the same name by Angela Lambert). She studied English at Queens’ College Cambridge and has an MA in Arts Policy. She is married with a daughter, a son and a step-son. She lives in London. www.devoniaroad.co.uk.

*

My Books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

Coming on 15 June 2024: Heroines of the Tudor World

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. These are the women who made a difference, who influenced countries, kings and the Reformation. In the era dominated by the Renaissance and Reformation, Heroines of the Tudor World examines the threats and challenges faced by the women of the era, and how they overcame them. From writers to regents, from nuns to queens, Heroines of the Tudor World shines the spotlight on the women helped to shape Early Modern Europe.

Heroines of the Tudor World is now available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK.

Out Now! Women of the Anarchy

Two cousins. On the one side is Empress Matilda, or Maud. The sole surviving legitimate child of Henry I, she is fighting for her birthright and that of her children. On the other side is her cousin, Queen Matilda, supporting her husband, King Stephen, and fighting to see her own son inherit the English crown. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how these women, unable to wield a sword, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It show how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other.

Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK.

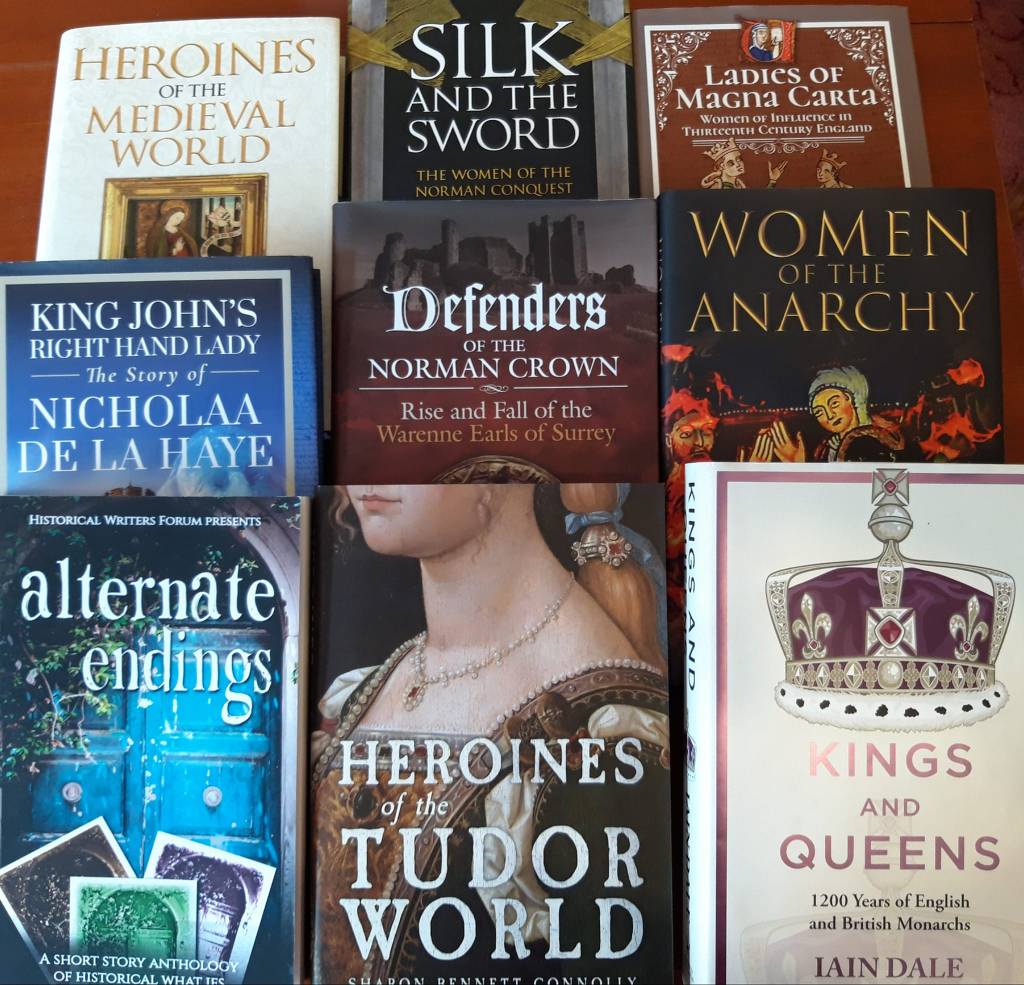

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops or direct from Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon. Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org.

Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

*

©2024 Jo Willett and Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS.